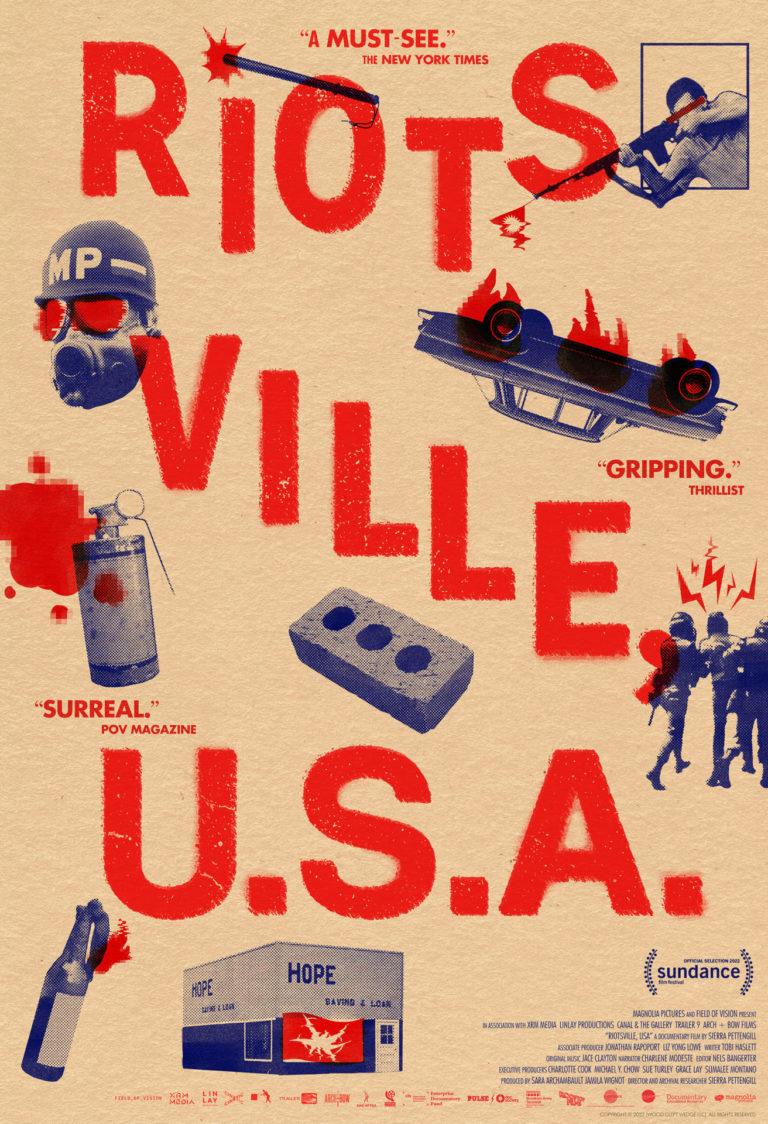

Synopsis : Welcome to RIOTSVILLE, USA, a turning point in American history where the protest movements of the late 1960s came into conflict with increasingly militarized police departments. Focusing on unearthed military training footage of Army-built model towns called “Riotsvilles,” where military and police were trained to respond to civil disorder in the aftermath of the Kerner Commission created by President Lyndon B. Johnson, director Sierra Pettengill’s kaleidoscopic all-archival documentary reconstructs the formation of a national consciousness obsessed with maintaining law and order by any means necessary. Drawing insight from a time similar to our own, RIOTSVILLE, USA pulls focus on American institutional control and offers a compelling case that if the history of race in America rhymes, it is by design.

Exclusive Interview with Director Sierra Pettengill

Q : Your inspiration for this movie came from reading the book by historian Rick Perlstein, Nixonland.

SP: I actually pulled it out today because I first read this [book] in 2014 so I was trying to refresh myself on it. It’s such a long journey since then. It’s an incredible book.

In the section where Riotsville comes up, [Perlstein] describes the Hughes Commission which was a panel put together after the 1967 riots in Newark [New Jersey]. The Commission concluded that, “The question is whether we should resort to illusion or finally come to grips with reality.”

Perlstein said, “The public was choosing illusion.” Then he goes through all of the really extreme reactions and policies that followed. Riotsville was listed as another illusionary solution.

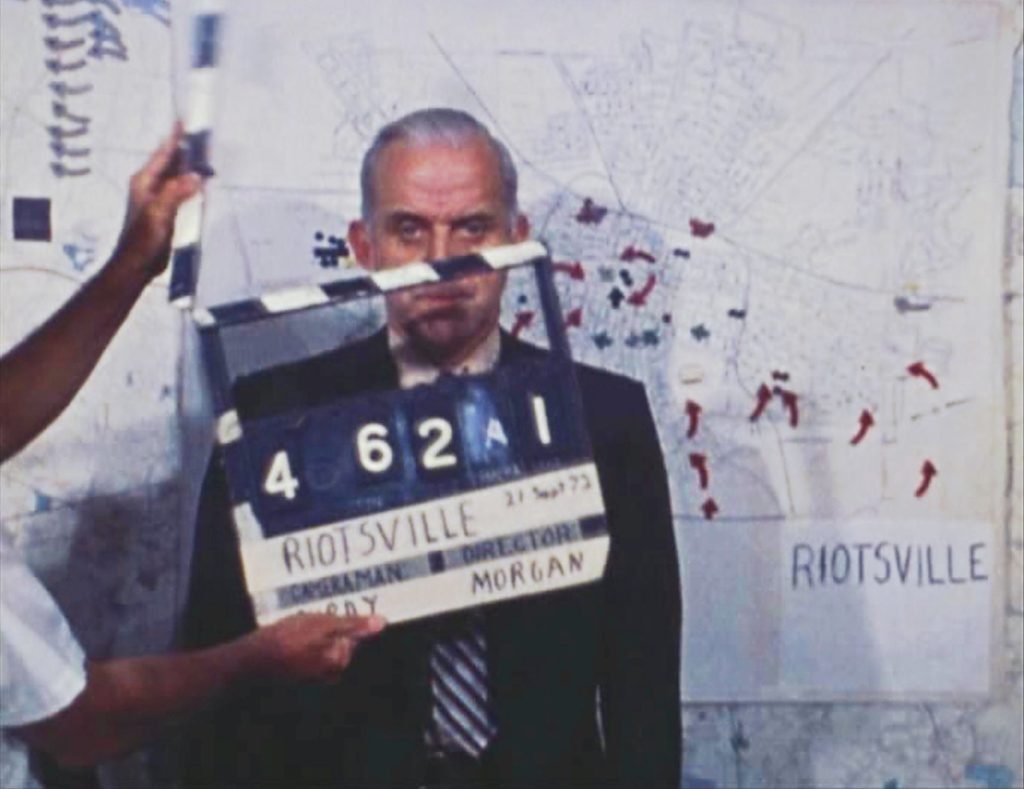

I was so [struck] by the description and looked it up to see what I could find — which was very little. I work as an archival researcher, professionally speaking. So I started pushing to find the village.

Q: It took you six years to make this film which consists of broadcast TV and U.S military archival footage. There must have been tons of TV coverage regarding the riots and police brutality. How do you map out the structure and what to look for?

SP: Slowly. Slowly. But it’s what I love doing. It’s not just the process of following a lot of threads until I feel like I’ve reached an end to it. I worked with a really incredible editor, Nels Bangerter, and we built up the structure together. As we figured out where we were going with the film, I kept researching all the way through. If we decided that maybe something like tear gas was important to include, I went looking for the best story line to follow from there.

It’s a combination of finding things in publicly accessible archives and going straight to these networks, and asking about what they have, which is a really expensive process. In recent years, it’s gotten even more difficult, as many of these news outlets have been bought by larger [conglomerates] — for example, ABC is now Disney, and that sort of thing. They’re really limiting access and charging really obscene amounts for licensing. It’s navigating that that was the hard part.

Q: The title “Riotsville” refers to a fake town in Fort Belvoir, Virginia. It was set up by the government in the late ‘60s for the police and the National Guard to develop and practice their riot management skills, especially to deal with the riots happening across the country at the time. When you first heard about that place, what was your reaction?

SP: I should say that it still exists now. There’s one being built in Atlanta. There’s one being built in Chicago. They’re all over the country. It’s not really a time capsule in that way. But I would also say that I don’t think these are necessary responses to people protesting in the streets. The government itself and the Kerner Commission looked into what caused riots. The answer was inequality and white racism, and it recommended putting billions of dollars into a social welfare [system] — which really doesn’t exist. The cause and the solution are there.

One of the other causes is police brutality. Most of the [protests] that built up on the street came in reaction to police brutality. So it’s really counter-intuitive to take a conclusion from your own government that says, “The way of dealing with this is to fund housing, employment, and eradicating homelessness” and then, have the reaction [of] “Nope. We’re just going to fund the police” — which is what Riotsville is doing — a really backward and counter-intuitive move.

I don’t know if really solving the problem is the goal or is it instilling more fear so that people are scared of their neighbors or feel threatened by something that is not actually a threat to their lives or livelihoods.

Q: During the Trump administration, we heard of “fake news” and “misinformation.”People assume those things happen because we are in the SNS era where you can spread fake news easily. But fake news and media manipulation have been going on since the ’60s. This film shows that many people didn’t realize it at the time.

SP: We’re watching a very different iteration of it. Whatever you are looking at in the 1968 era “Riotsville USA” is still there. I think digital news journalism — newsrooms, foreign correspondents, local newspapers, local television stations — is independent and they’re still funded. Whatever the flaws are — and there are many — in their coverage, what we’re seeing now is in part of a crisis due to, on one side, a corporate consolidation of media, and, on the other side, a really hollowing out of funding for any kind of local community reporters. Today’s crisis is a different one in terms of the failure of the media to properly respond. It’s driven by a different set of systemic failures.

Q: In the film, a grandmother in Pontiac, Michigan, who saw terror in the street, led her to go to a pistol range to practice shooting. Showing those things on television was intended to evoke feelings of animosity against black people rather than showing events impartially. And it was done by such mainstream media as NBC, ABC, and CBS.

SP: It’s harder for television news to think about how to cover long, systemic problems that aren’t flashy. In the film, a great example is the series of community meetings that happened in Liberty City in Miami over [several] days. It’s people calling for conversations with politicians, and posting their demands — and they were being ignored.

I would argue that’s a harder, more interesting and illuminating thing to cover as a television news reporter. It requires a long-term commitment to a community rather than it is to go shoot a cock farm on fire — an instant image that communicates something very quickly. A large part of what we’re showing in the film are systemic problems that don’t make for great images in the same way that moments of violence do. We’re constantly getting fed the wrong type of thing.

Q: Public Broadcast Laboratory [PBL] was aired by National Educational Television, a predecessor to PBS. They aired a program about police brutality against the black community, and PBL ran footage of Jimmy Collier and Rev. Frederick Douglass Kirkpatrick singing , “Burn Baby Burn,” a civil disobedience song they wrote in 1969. The Ford Foundation withdrew funding from PBL and the station was taken off the air. How should today’s media cover issues of racism and police brutality?

SP: There needs to be funding for independent media. PBS used to play that role like ITVS Independent Television Service. There’s a lot of incredible, radical films authored by people from all sorts of communities that were funded and aired in experimental forms — not in your standard way.

They’re really surprising to look at now, to see what’s on television and what is funded. [We’re] really seeing the shrinking of those budgets. I think the lack of investment in independent media and trusting the voices of people who are reporting from within their communities is a big part of the problem. And it’s sad.

Again, we’re in a very different media landscape. People have Twitter, TikTok and all sorts of other ways that provide documentation which makes a difference. But I think it’s allowing independent voices to take up space and determine their own storytelling.

Q: You made such an eloquent point throughout the film. What do you want audiences to take away from seeing it?

SP: I want it to be clear that the system we live in is not automatic — it was designed and can be deconstructed. It was physically built, like Riotsville, and the idea that we are trying to come up with new solutions as if they hadn’t existed for many decades should be eradicated. We’ve spent enough time living in a loop that pretends that we don’t know what needs to be done, which is a major redistribution of income — of wealth — in this country. If we keep ignoring it, this is just going to keep happening.