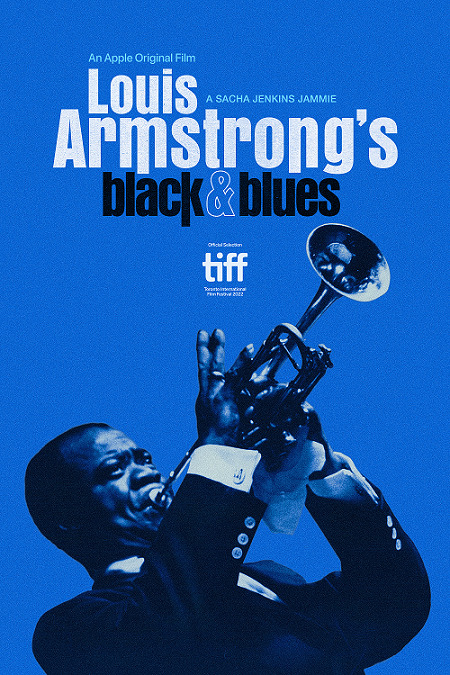

When Louis Armstrong died in 1971, newscaster Walter Cronkite proclaimed, “We aren’t saying goodbye to Louis tonight, because a man’s music does not die with him, certainly not this man’s.” Armstrong was enormously influential and it’s difficult to find another musician who has left such an enduring mark on the industry and the world in recent memory. But what Sacha Jenkins’ documentary Louis Armstrong’s Black and Blues achieves is more than to just pay homage to Armstrong, but instead to invite audiences to feel as if they’re experiencing a movie made with him as a living and breathing participant.

There is evidently a tremendous amount of archive footage that exists of Armstrong performing and speaking with interviewers from the years in which he was active. Jenkins and editors Alma Herrera-Pazmiño and Jason Pollard do remarkable work in piecing them all together so that it seems as if Armstrong is answering questions being asked of him within the film’s narrative. While each audio and video clip comes from a different source and varies in quality, they’re constructed in such a fashion that it feels cohesive and smooth. There is a clear narrative to this story, one that starts with Armstrong passionately playing music and fills in the gaps of his life, with highs and lows mixed in, along the way to the legacy that he has left today.

Armstrong’s music speaks for itself, and starting with the camera focused firmly on his trumpet is fitting. There are many performances showcased over the course of the film in between the many conversations featured with Armstrong and a number of his confidantes. They are interspersed in a manner that serves to illustrate Armstrong’s undeniable talent, which further underlines the unfortunate fact that he still faced racism from audiences and talent bookers throughout his career. One clip is noted as the only known existing footage of a live recording session, revealing another side to Armstrong and the way in which he put all of himself into each time he came to the microphone.

Hearing directly from Armstrong is enlightening, especially considering his very distinctive voice which many will surely recognize. He speaks in a very honest manner when he is having a direct conversation, and it’s particularly interesting to hear him swear and give his unfiltered opinion. His musings on his childhood and his career, as well as on civil rights in the era of Brown v. Board of Education and Eisenhower, are informative and eye-opening given how he generally existed between worlds and found success even during an oppressive time of segregation. As colleagues and historians comment, Armstrong understood his place and his influence, and used that as he saw fit, including to ensure later in his career that he didn’t play somewhere he wouldn’t otherwise be allowed to enter or stay.

Those who are very familiar with Armstrong’s history may not find many surprises in the narrative that has been constructed here, and, along those lines, it’s impossible to capture a person’s life in under two hours. But what has been put together here is a comprehensive snapshot of the many things that Armstrong was, defining him not only by his music but by his influences, role models, and the people who were in and out of his orbit. Given the seamless incorporation of so many soundbites of Armstrong from throughout the years, this film at times feels like an intimate conversation with a man who died half a century ago. His words echo and resound today even if he couldn’t have known what present-day society would look like, but his intuition and deep understanding of the world comes through in a riveting manner in this thorough documentary.

Grade: B+

Check out more of Abe Friedtanzer’s articles.

Louis Armstrong’s Black and Blues is streaming on Apple TV+ and also screens at DOC NYC Wednesday, November 9th and virtually through Sunday, November 27th.