Q: Working with Nan Goldin, telling this story with her, seems to have been a totally new and different type of challenge for you. Where did you start with Nan? What was the entry point?

LP: First of all, Nan sends her regrets. She would have loved to have been here, but she had a conflict.

Every film is a collaboration and the director is often alone even in situations like this. But you’re right, this film was unique for a number of reasons. First, some of the news about Nan’s work, and she was a clever collaborator in the telling of that and her personal experience. And secondly, she inspired the film. At the end of 2017, Nan read Patrick Radden Keefe’s article in The New Yorker [“The Family That Built an Empire of Pain”, October 30, 2017 issue] that was about the Sackler family. It was a shorter version that he expanded into book form, “Empire of Pain”.

She had just come out of her own OxyContin addiction, as you see in the film, and she created this organization [seen] in the film [P.A.I.N. (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now)]. We met for another reason, and she told me she was looking for additional producers and was trying to talk to them. So that’s how I got in. I felt she entrusted it to me. Originally, she had been thinking about the focus for her pain and that’s what I thought as well. It kindof stayed within my previous works about contemporary stories of people confronting power. Then as I began working on it, it became really apparent how important it was to talk about her, to do a portrait of Nan.

Q: So in creating this new documentary portrait of her weird life as an artist and as a woman, you have this process of re-documentation and re-textualization, finding new truths in both her work and what her work and life has led to in her activism. It seems like a bit of a miracle that you were able to do that with her. Can you talk a bit about approaching that?

LP: Yeah. Oftentimes I come into a screening at the end just to acknowledge the emotion of the film and how it matches herself. It’s incredibly moving how she does it in her own work and how she did it with me, and with the editors and producers on the film. It’s quite extraordinary how much she shared about herself. The experience of making it was also incredibly emotional, to sit with her and do these extensive audio interviews.

And then somewhat gradually over time, I knew that the Sackler throughline was essential. Then quickly I learned about the activism she did during the AIDS crisis and I knew immediately that those two things had to converge in the film, that that was the convergence moment. I wanted to put them in dialogue for a number of reasons, one being the historical amnesia we have in this country. We forget, and we need to remember AIDS, we need to remember those we lost, we need to remember those who struggled, and to keep their memories alive. That was really important.

A key moment in this process of making the film was when I saw Nan’s art work about her sister Barbara, and it’s called ” Sisters, Saints, & Sybils”, it’s a three-panel installation. It’s devastating, I was [wrecked for days]. Barbara [was] a young woman who was rebellious and outspoken and sexual at a time when that just wasn’t accepted [for women]. That for me becomes really a [key] part of the film: her sister, and not just the tragedy of her loss, but this fighting against denialists, that there is this cruelty in this society and it destroys people who are different or who are outsiders. And then, to pretend that that doesn’t exist — it’s almost that the cruelty [is] bad enough, but this is more vivid: this idea that it’s not happening. [This caused] a sense of rage that Nan felt about her situation.

Q: That’s always been a very powerful element of her work. The rage she feels at the addiction compelled her to document these lives.

LP: Yeah, and Nan and I had these really deep conversations about it. All of her work is profoundly beautiful but maybe it’s in a less direct way. My outlook is political, maybe emotional in a geopolitical way, and her work is profoundly political in this sortof intimate way.

I was situating her work, not leaning it towards [a particular way]. She felt it was important that when you talk about the radicalness of “queens”, that it wasn’t a “thing” or a dare to be a rebel. They just were, they were being themselves, and saying “fuck you” to society. And sometimes they protested. It was [about] how to present that in the film that is true in terms of [their lives].

Q: You talk about the throughline of activism as a guidepost for you and within the structure of the film. Can you talk a little bit about the melding of the Sackler story with her personal story?

LP: Yeah. For me, it was the book. It was really the book in the sense that I might be the right filmmaker to do this movie. Whereas I got a portrait of an artist, a renowned artist who I loved. I was kindof obsessed with these actions she was doing with museums, and I was obsessed with the failure of our government and the failure of the judiciary system, and yet here it was in these cultural spaces where there was emotional reckoning. That feels so essential to me, to be able to tell that story and to document it.

But then I think it couldn’t just be that. For me, it was supposedly the challenge of the film, and what was the most thrilling thing about making the film were these fields juxtaposed, the past and present. So for instance, you go from the middle of an action to back in time to Nan invading New York or dancing. To me that’s like, here is where Nan enters the art world, and then you go to, here’s where she conquers the art world, and that’s when Nan is the renowned, famous artist being collected by all the institutions that she’s protesting. But oh, let’s rewind, and let’s see how she conquered the art world.

That’s the kind of stuff that you usually can only do if you’re writing a script. Partly because she has a epic life, but also because it was material to tell it as a nonfiction filmmaker. So the fact that filmmakers like Vivienne Dick documented Nan’s loft on the Bowery, and that Betty Gordon was in Tin Pan Alley — that’s incredible to be able to cut to Nan in Variety and at the bar in Tin Pan Alley. I loved [that], because who has the [framing] of life that Nan has with that kind of art and also can be her photographs, obviously, and then this other part of her.

Q: Can you talk a little bit about the art world in the context specifically of the intense nature of the opioid crisis, which clearly is central to the film?

LP: Yeah, they didn’t really want it to be — and I don’t think this is a critique of other types of action, like political actions and other actions that are disruptive. But they really wanted to be respectful of the spaces and people who work in the spaces, and there’s a lot of support by the museum staff. They even protested that happening and they had support for that leadership. This is why we have to have that conversation. There are dark, dirty mysteries in art and how it comes to be in museums of big art, . . . and we can’t ignore them. The Sacklers are obviously uniquely [capable of] wanton greed and lack of [integrity]. But they’re not complete outliers.

The boards are actually thinking a little bit of this. I do think these questions are fair when it comes to arts institutions.

Q: I think it’s being understood that the existential struggle is perhaps a procedure of both sides. Meaning the institutions need to survive in a country where there is no governmental support for the arts. You probably wouldn’t want that in the sanctity of our government, but the existential struggle of actual people, many of whom are artists that the institutions are involved with, is actually part of [it].

LP: Yeah, I agree. That was not an immediate consensus, but since it’s put that way, Nan and Kane actually did the first action at the Met, and that didn’t even make a statement. So it took a year and a half of going to institutions and doing these actions. And also talking to investigative journalists, many, many, many others. This shift happened because of the journalists who would not let this story go away and end.

Q: Talking in the context of your signature narrative elements and ideas that you’ve brought to your films, and one of them is an investigative journalistic impulse, this strategy, this humanist impulse. You focus on people rather than ideas about people or pop culture or any one person. But there’s something new in this film, and maybe it’s catharsis. You and Nan actually got something done.

LP: Yeah, there are many levels of catharsis there. I make a documentary like an experimental art form. Like . . . Nan’s way of storytelling and constructing from her own visual language, that’s not just a reaction to a story that’s character-driven in the same way. That was really liberating to be able to make a film with Nan that could let me have a different range of voices, and obviously, this range of emotion that existed in Nan’s work. I find it moving, and if you didn’t feel that, I think I would absolutely have failed this film. I hope you felt that, because Nan does deserve it.

Q: Thank you, Laura.

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.

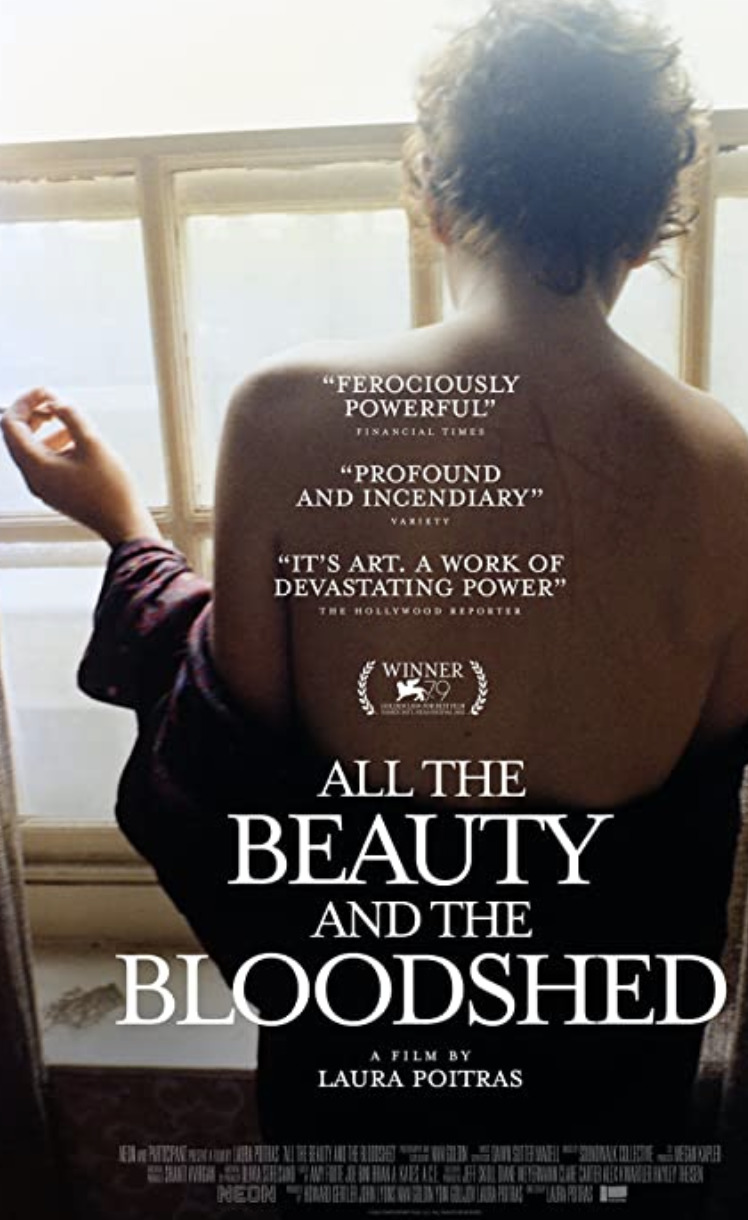

Here’s the trailer of the film.