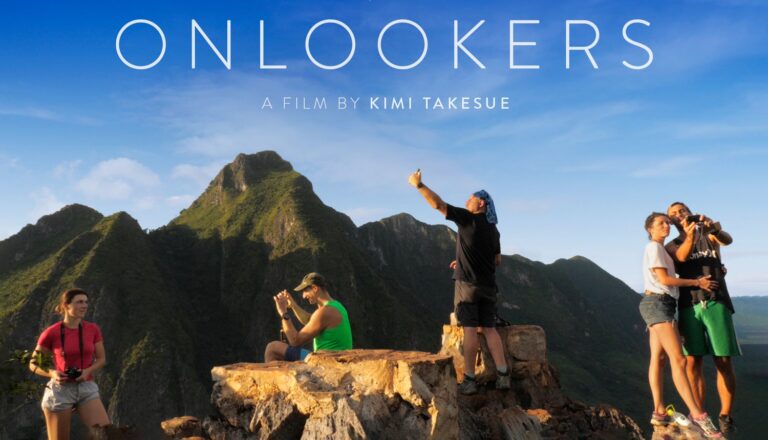

Synopsis : ONLOOKERS offers a visually striking, immersive meditation on travel and tourism in Laos, reflecting on how we all live as observers. Traversing the country’s dusty roads and tranquil rivers, we watch as elaborate painterly tableaus unfold, revealing the whimsical and at times disruptive interweaving of locals and foreigners in rest and play. Drawn to spectacle, tourists swarm to magnificent Buddhist temples, the ordered rituals of monks, and sites of dazzling natural beauty, then recede like a passing tide, leaving Laotians to continue with their daily lives. ONLOOKERS transports viewers on a sensorial journey of deep looking and listening, inviting audiences to reflect on their own modes of tourism, while asking the looming existential questions: Why do we travel? What do we seek?

Genre: Documentary

Original Language: English

Director: Kimi Takesue

Producer: Kimi Takesue

Runtime:

Exclusive Interview with Director Kimi Takesue

Q : You originally were born in Hawaii and then grew up in Massachusetts. How did you develop an interest in filmmaking?

KT: My father is Japanese American and my mother is Caucasian. I grew up as a child in Hawaii. I don’t know if I’m third or fourth generation Japanese-American. My family immigrated from Japan in the late 1800s and then my grandparents were born in Hawaii, but they retained a lot of Japanese culture. I grew up there as a child and then my parents divorced.

I moved with my mother to Massachusetts, but would return to Hawaii regularly in the summer. I’d spend about three or four months there a year and spent a year there growing up. I had a lot of connection to Hawaii growing up. My experience of being biracial and having a pretty fragmented cultural experience moving between these different cultural zones, very much informed my sensibility in terms of how I approach my filmmaking.

One of the major themes that I’m interested in in the film “Onlookers,” is about exploring different cross-cultural encounters. I am fascinated by that meeting point when people from very different worlds come together and search for some mode of connection or communication. I’ve explored that theme in the context of travel and tourism in a number of films including this one.

Q: You were a model, the campaign girl for a Coke campaign, in Japan years ago.

KT: I was the Coca-Cola girl of Japan in I think it was 1984. I represented Coca-Cola for the year. I did all the commercials. I did all of the posters. It was a big deal then. It was like the biggest thing in life I could achieve really, from a Japanese perspective, at the time.

Q : How did you make a transition into filmmaking — how did that lead you in this direction?

KT: It’s funny. What I found most rewarding about modeling was the fact that I got the opportunity to travel to Japan. That was my first time out of the country. At that time, there was no email, everything was by fax. It was just so foreign in terms of traveling to Japan. Having that experience was really special. Then I ended up going to college and I majored in cultural studies and women’s studies. This interest in interacting with new cultures and people has always been an interest of mine. In terms of that kind of trajectory with modeling, I really pursued it as a way initially to earn money, go to college and gain some financial means.

In the end, it wasn’t something that I actively pursued but it was an incredible opportunity for me because of what happened — I was the first Teijin model. I was the campaign girl for Teijin, the textile company. Then I went to Tokyo and met the people from Coca-Cola. They hired me and honestly ,I think the appeal to them was that in some ways I really didn’t care that much about it. It wasn’t like I was really desperate or trying so hard. A lot of times, people are attracted to people when they’re indifferent in a sense. I think it wasn’t something that I was so hungry for — I wasn’t indifferent — but I was very relaxed about it. I think they liked that quality in part because I was just a regular teenager.

Q : How did you come to film this type of exploration? Your approach to filmmaking, which explores the relationship between viewers seen through the camera — it asks viewers what they are looking for, what have they found through the vision? After you’ve seen so many films in the past, it seems like a similar concept to Frederick Wiseman’s. What was the intention behind that and how did you come to this approach?

KT: In terms of my biracial experience and growing up as an observer to some degree, I was never a person that connected completely to a single group. I found myself having to assimilate in different ways, observe and critically assess different cultural messages that I was getting from each parent. They presented very different perspectives. I developed a certain critical ability at a very early age, and really took on the vantage point of an outsider and observer.

That really informed my sensibilities and approach to filmmaking. I’m someone who is a bit removed as an observer, but at the same time, I find a lot of points of connection and ways to assimilate quite easily into very different situations and cultural zones. The work moves between this vantage point of an outsider and insider. I fluctuate between those vantage points. You see that in “Onlookers” in some ways. The perspective of the camera is quite detached and removed. You see my sense of identification with different people and at moments, [my connection] with different people can be more intimate at times.

Q : In the pre-production stage, documentary filmmakers make a schedule when they shoot, where to shoot and who to interview. With your film, it seems that you don’t plan much ahead of time. How do you find a subject, and determine what to shoot in a film — how do you choose the location and all that stuff?

KT: It’s really an exploratory approach because I’m just driven, first of all, by curiosity in the most basic sense. I’m interested in traveling to Laos. It’s a place I’d like to visit so I went without preconceived notions other than the fact that this is a culture that I’ve heard has a very special, slow, tranquil quality to it. That’s what I had heard — it’s a very distinct culture in that respect. I had heard that there’s this distinct sort of peacefulness and tranquility to the people in that place.

That attracted me. And then there’s the awareness that Southeast Asia is going under so much rapid change, globalization and development, and it’s a country that hasn’t developed at the same pace as surrounding Southeast Asian countries like Vietnam or Cambodia or Thailand have. I was very curious to visit it sooner rather than later. And I’m going with the camera and not with a set agenda or a set of expectations. Honestly I was gathering material and footage, but I really didn’t know if there was going to be a film. I think that’s really important in making this film because it really changes if you have a particular agenda.

It’s a different mode of interacting with people and places because it becomes a bit aggressive in the way that you want something. It’s very different when you truly are just responding to what is a rising of interest and are really responding spontaneously to that. This piece basically operated in that way, where I am just literally wandering and maybe following a certain kind of prescriptive tourist path, rather than a standardized path. I’m deviating from that standard path to a certain degree, but I’m giving myself the time — shooting entirely by myself — to just enjoy and respond to these different moments that unfold. I’m just looking very intently.

This piece is so much about looking and listening deeply. I might see a moment or get a sense of a frame. The film is very formal in the way that it’s shot. I have a very clear idea of certain compositions that interest me. It might have to do with the landscape, or with the architecture; it might have to do with some sense of how people are moving through a space. I’m fixing the frame in a very formal and authored way, and yet what unfolds within that frame is completely spontaneous. I’m interested in that tension between naturalism and stylization.

A lot of times people think that moments are directed because there is a certain kind of choreography and, in some ways, perfection. It’s about how people move through the frame and are aware of the choreography, the color, the light. Obviously it’s sort of the substance and content of the shot itself and what is being said within the shot. All of these elements have to cohere in a certain way to give it an aesthetic appeal that’s very important in this piece. It really is a very patient and spontaneous form of filmmaking.

Q : Did you take at least a couple weeks prior to you shooting? How do you process that because it seems like the observational stage has like a long time before you actually shoot it. And even if you started shooting, you don’t know when to cut, where to cut. until you actually ended up in a, you know, editing stage most of the time. So it’s just an interesting process of actually going through that process.

KT: The thing is, none of these moments can ever be repeated. So there’s no point in waiting. You’re just fortunate to get it once.

Q : Right.

KT: There’s so many kinds of aesthetic concerns on top of the deeper content of what sort of shot is ultimately revealing. There’s so many aesthetic concerns. For example, the light might not be right or the sense of color may be off, so to get all of these elements in sync is extremely hard. There’s so many moments that you might find have one or two of these elements but don’t have all of them right. So for a film like this, I can’t use any of those other moments because it has to have a certain kind of perfection to work aesthetically. You could observe all you want in preparation, but it doesn’t mean you’ll ever capture that particular moment again. I can say that observation can come into play in that I might see certain patterns like, “Oh, this is a place where people arrive, say a dock, that people come to.”

This seems to be the time that they come and go. I do take note of something like that because, it’s like, “Okay, if I want to catch them arriving in the morning, I need to be there at seven o’clock in the morning.” It’s more of that kind of awareness. But I could easily see a moment and be like, “Okay, I need to come the following day and then it’s all different.” It’s a different sequence of people, personalities, combinations, at a pace that if they walk up the stairs differently, everything changes. It could be better, but it might not be right. So much of the piece is about letting a moment unfold. I look at this as almost photographic. I could reference the French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, known for capturing a decisive moment or frame, where all of the elements are just right.

I almost look at these as extended decisive moments in duration. Everything has to be just right, but it’s happening in time. It’s an entire scene unfolding in a very particular way. To me, each of these scenes, each of the tableaus, have their own internal rhythm and almost exist as like a mini-film unto itself. You see a lot of times, there’s a pattern of people entering into the frame and exiting it. Part of what I’m interested in too, is how do people engage with, consume, and interact with places, architecture, other people — literally, how they come in, and then leave. It’s interesting to see a space — a temple for example — before someone arrives, how they interact with it, and then how they leave it. In a sense, how do we look at that temple differently after they’ve left the frame?

In one sense, we can talk about the impact of tourism in a negative way, in the sense that it’s almost an invasion of places and people. When you see, for example, a very ancient temple that’s thousands of years old or a mountain, there’s something very powerful about the ways in which people can engage with it, corrupt it almost like commodifying it or whatever, but then they leave. Yet we’re still left with the majesty or the power of that temple or mountain. It’s interesting to reflect on that. To me, each shot kind of has its own internal rhythm.

Q : It’s fascinating, what you just mentioned about the speaking of invasion. Obviously it used to be a French colony. Then America had the Vietnam war where they bombed Laos. What’s amazing about how you show this — the tourism and the local people — not just the negative side of it. The Laotian people rely on those tourists to make ends meet economically. They preserved those historical buildings as well; it’s a contrast. What’s amazing at the same time, you see the local people serving tourists and the tourists blasting music in the background. It’s fascinating how you contrast that. How did you frame and compose those shots? You’re not just a director, you’re also a cinematographer as well. So composing the shot is very engaging, particularly when you’re shooting a long shot.

KT: I’m responding to a lot of different elements. On one hand, I’m responding to the environment, the landscape — which becomes like a character to me. I’m responding to architecture. And I’m fascinated by the way that people kind of move through these spaces. There’s a really strong sense of portraiture too. So even though I’m not singling out individuals in a really close up way, if you have the time to engage with the image — because they’re long takes — you’ll discover the complexity of each image in terms of the environment and the details that exist within it. With all the little signs that give you information, there’s an opportunity for a deep sense of portraiture. For example, that last shot where you have a whole procession of monks, on one hand, you could see this as a long procession.

But, if you look at each of the monks’ faces, each one is just so distinct. Each one has a sense of personality as they go through that process of taking alms.

Even though I am looking at things in a formal way — in terms of composition — I’m ultimately looking at human behavior in a very humanist way. What is revealed in terms of the piece is so much about capturing the potential and limitations in the way of human experience. We see so many things that express a kind of fallibility and the foibles of the human experience. You see moments of awkwardness and uncertainty as people travel.

You see moments of vulgarity and the ways that they’re intrusive. But you also see real desires too — to experience new things and moments of exhilaration. You see the whole range of human experience. Part of what I like is for you to see that within a frame.

The viewer is given the time to watch all of that unfold rather than in a fast-paced film where it’s very much dictated — like, how do you view this? I control that in terms of the editing. I’m giving you a moment. Obviously, it’s a highly authored frame. Everything is spontaneous but you have a lot of time as the viewer to really engage with it, to watch whatever interests you and to interpret it.

Q : In that process, it becomes like a Stanley Kubrick movie, where you discover something new each time you view his films. It’s an engaging way of filmmaking. But when you are making a film like this, sometimes it’s impossible to describe this type of film in one line. How do you pitch this to the producer or investor who funded you the money to shoot this film?

KT: I have no producer or investor.

Q : You basically funded on your own?

KT: I’m a professor so I get a little money through my university. I teach at Rutgers University in Newark. I’m a professor in filmmaking. There’s an interview that I did with Filmmaker magazine and the line they used with it is that we need work that’s impossible to describe and that’s exactly the point. I struggle to describe this work. It’s very hard for me even after I make it. To try to somehow distill it because I feel that it really limits the expansiveness, what I hope is the expansiveness of the film.

You can give it a literal synopsis in terms of the aspect of tourism, but it’s about much more than that, in terms of ways of seeing, of being and of feeling and listening. I feel that the questions it raises are more existential too. It’s very difficult to describe. This is a big challenge because in terms of funding, people have to go through this process of explaining. If I were to write a proposal about this film before I make it, I go with expectations. It’s impossible for me not to have that, so that changes the whole process of making it. This film becomes impossible to make.

For someone like me, that affects my mind; I carry that with me. It’s a very different, difficult kind of filmmaking to do because it is unknown. I don’t know what is going to happen. It’s very hard to explain or justify or, I don’t want to explain or mythologize it before. Then afterwards, it becomes difficult to describe because it just feels that it’s kind of a reduction. It’s part of the difficulty of distribution of a film like this. How do I compress this into a sound bite, or into an easy synopsis.

Unfortunately, this is the problem. We live in a culture where everything is supposed to be reduced to a sound bite. Yet the argument of this film is, in a sense, anti-sound bite. It’s anti-ADD culture. It’s about the fact that you need to actually watch it closely, listen and take time with it. You can’t multitask while you’re watching this film in order to enjoy it. You can’t just consume it in that way while you’re doing your email, watching it and listening, or taking a phone call. The film is really kind of political in that sense, because it is about the need for attention and it’s a call for the importance of cultivating attention and the ability to look carefully and listen.

Q : What’s your next project? Do you have anything in mind right now?

KT: I have this one piece that is a series, or more like an art installation piece. I don’t know how it’ll show up, but it’s a series of video portraits of Laotian people who work in the tourist industry. It’s moving images but they’re like single portraits of people. I’m working on a project in Cambodia about tour guides who take people to the killing fields and other dark tourism sites. But, with COVID and all the changes, it’s definitely had an impact. The next screening is at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. It’s having its New York premiere. Then after that, it’s going to the Krakow International Film Festival in Poland.

I’d love to show it in Asia as well, somewhere in Japan. These festivals get thousands and thousands of entries now and it’s really hard to even get it watched carefully.

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.

ONLOOKERS makes its NY premiere at Prismatic Ground on May 4th at BAM:

https://www.onlookersfilm.com/

https://www.bam.org/film/2023/onlookers

Here’s the trailer of the film.