There is no one who will tell you that the situation in the Middle East is not complicated. Numerous parties have tried over the course of seven decades of Israel’s official existence as a country to negotiate some sort of agreement that will ensure safety for Israelis and self-determination for Palestinians. Among the most high-profile and initially optimistic of them were the efforts undertaken by United States President Bill Clinton to implement the Oslo Accords negotiated in 1993.

The famous players on both sides were Israeli Prime Minister Yitzchak Rabin and Palestine Liberation Organization Chairman Yasser Arafat, sworn enemies with very different backgrounds and priorities. But there was also a team of negotiators that was instrumental in ironing out all of the specifics to determine how all parties might be satisfied with the agreements and work out problems that arose along the way on a presumed road to peace.

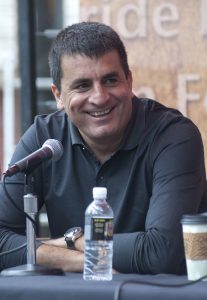

Director Dror Moreh’s previous film, The Gatekeepers, earned an Oscar nomination in 2012, for its incisive interviews with the surviving heads of the Shin Bet, Israel’s secret service, whose perspectives on Israeli-Palestinian relations have shifted considerably since holding their posts. With that film, Moreh showed that he is deeply committed to showing the bigger picture with everyone considered, and he applies that same laser focus to this portrait of the human factor, the quotient that can’t be neatly calculated but plays strongly into the process of ironing out differences and achieving a common good.

I had the chance to speak with Dror about The Human Factor, which premiered back in 2019 at the Telluride Film Festival and screened at a number of festivals in 2020. Sony Pictures Classics will release the film in theaters on May 7th.

An exclusive interview with Director Dror Moreh

Q: What appealed to you about this subject matter?

Dror Moreh: Well, it’s my life. I live in Israel most of the time, and I have kids here, and it’s basically my life. I wanted to understand what went wrong.

Q: What made this seem urgent or relevant at this moment in time?

DM: It’s always relevant. For me, the interesting thing is that, when I spoke to Dennis Ross, the main protagonist in the movie, I asked him if he would be able to share with me – because he was there from the beginning inside the room with the president, with the secretary of the state, with the prime minister, with the head of the Palestinian Authority, with President Assad – what happened inside the room, the real story. Not the very well-drafted statement to the press, but really what happened inside the room. He said, let me think about it, and when he said yes, I was very happy. It was a long process of interviewing him. I interviewed him for 35 hours, and I learned a lot doing that, about what really happened inside the room. And I think this is what happens when you watch the movie.

Q: What did you learn about Yitzchak Rabin and Yasser Arafat?

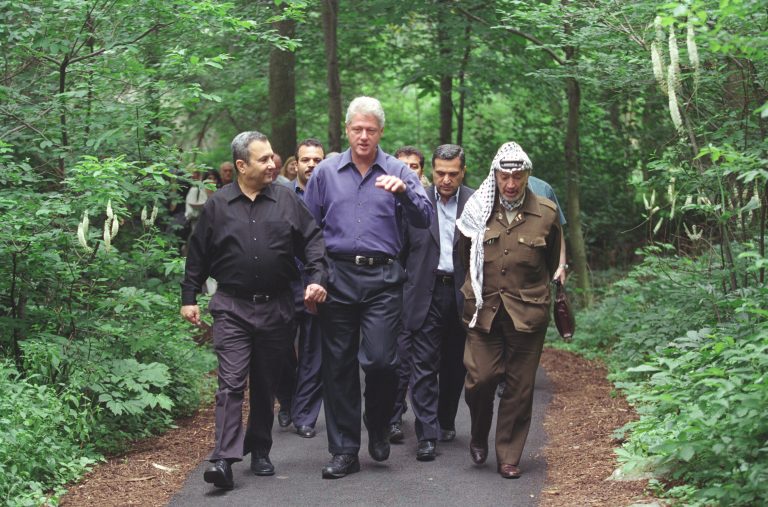

DM: First of all, what I learned and what surprised me was the importance of the human factor. What’s amazing for me is that I had heard all the stories inside the room, and then I had all those amazing photographs that had never been shown before. Only in this movie, you see those photographs. To answer your question, you can see the first time that Rabin sees Arafat and doesn’t know what to do with this guy. He’s supposed to shake his hand. You’re inside the White House, inside the room, and you see how he looks at Arafat. What I interpret from that look is basically, what am I going to do with this guy? And then you see the meeting three years later, where they are much warmer towards each other, and much friendlier. You see the kind of progress of the human factor and the human relation between those two leaders.

Q: This film presents a very sympathetic portrait of Bill Clinton. Did you have any interest in getting him to participate in the film given that he is still alive?

DM: No. I could have interviewed secretaries of state, and I did that for another project I’m doing. I interviewed Madeleine Albright and Jim Baker. But I didn’t want politicians in the movie. I wanted only the professionals and to have it told from the point of view of the professionals. Politicians have reputations to keep and narratives they build for themselves. For me, it was important to speak only to the professionals. Their job was to bring the two sides together and create, hopefully, a peace deal which they failed in that case to do.

Q: There is a good deal of humor to be found in the film. Did you expect that when you set out to make it?

DM: No, not at all. And it’s amazing because you think that there are dry people in those places, and it’s one of the most fun things about watching the movie with audiences, how much people laugh during the movie. You laugh a lot. Again, it’s connected to the human factor. If you allow me to tell one anecdote from the movie: Rabin told the peace team before he met Arafat that he had three conditions. One of them is that Arafat will not kiss him. He didn’t want to be kissed by Arafat. The American negotiator built a mechanism that they would shake hands while holding his bicep so that he cannot get close to that. They coached President Clinton on how to do that. I have the picture of them coaching President Clinton, shaking hands while holding him far away on his bicep. There are very funny and human moments like that throughout the movie.

Q: I don’t know if you remember, but we last spoke eight years ago about your film The Gatekeepers. What has changed for you and your perspective since then?

DM: It’s a good question. I would say, if I had to put it in a nutshell, I’m much more desperate now than when I finished the work on The Gatekeepers. At that time, I felt like it was almost the last chance or the last cry-out for peace. Now, the two-state solution doesn’t exist anymore. I’m much sadder and more pessimistic about the prospect for peace here. This is what changed from The Gatekeepers to this.

Q: I’m sorry to hear that. I know that Israel is having election after election and it doesn’t seem like anything is becoming clearer. Is that part of the problem?

DM: The election after election is in part because of one issue, that Benjamin Netanyahu’s criminal activities mean that he has to go to court on three different accounts of whatever. He tries to resist that by creating political havoc in Israel, so it doesn’t really connect to the peace process. The problem of the peace process is the lack of leadership. One of them is definitely Bibi Netanyahu, who doesn’t have an ounce of leadership in his bounces. The other part is also the Palestinians. Mahmoud Abbas is now almost ninety years old, and the decisions that will need to be made in order to reach peace are so gigantic and huge that I don’t see any kind of leader on this side or the other side that can really bring that to bear.

Q: And what do you think about the United States? Donald Trump is someone who was seen in a lot of ways as friendly to Israel and definitely not friendly to Palestinians. Do you think that there is some hope for someone to moderate from the U.S. going forward?

DM: Look, I interviewed Jake Sullivan and Bill Burns for another project that I’m doing. I think that if they try to reach peace now or to moderate, they should be hospitalized in a mental hospital. I know that they are very solid, smart intelligent people, but I don’t think they will even try to get their hands in that. They have so much on their plates to deal with now, why should they?

Q: How has this film been received, and has it had a different reception based on where people have seen it?

DM: The film is going out now in America and also in Israel. In every screening I’ve been at, the responses are amazing. They’re heartwarming and people are responding very strongly. I’m happy with that and I’m looking forward to what will happen in America.

Q: You mentioned a few times another project that you’re working on. Can you tell me a bit about that?

DM: For the last six years, I’ve been working on a huge project that has a working title of Corridors of Power. It deals with the subject of the promise of Never Again, and especially after the collapse of the Berlin Wall, when America stood as the only superpower. I am getting inside the decision-making room in America in the White House. Whether it’s the situation room or the oval office, trying to understand what the calculations were inside the room when they faced atrocities: Rwanda, Bosnia, Kosovo, Libya, and Syria. Basically, I’m bringing the audience into a huge drama inside the room, and the debate, shall we intervene or shall we not intervene? It’s also, as you can imagine, a depressing project. There are fewer funny moments in that. But it’s also about the human factor and understanding the human soul and the human capacity to change and try to create a better world.

Q: I hope that peace is something that is in our future. I wish you plenty of luck with this film and other projects. Thank you for speaking with me today.

DM: Thank you very much. It’s been a great pleasure. And I hope to speak with you again on my next movie!

Q: Absolutely! We’ll put it on the calendar for whenever that is.

Here’s the trailer for the film.

The Human Factor will be released in theaters nationwide on May 7th.