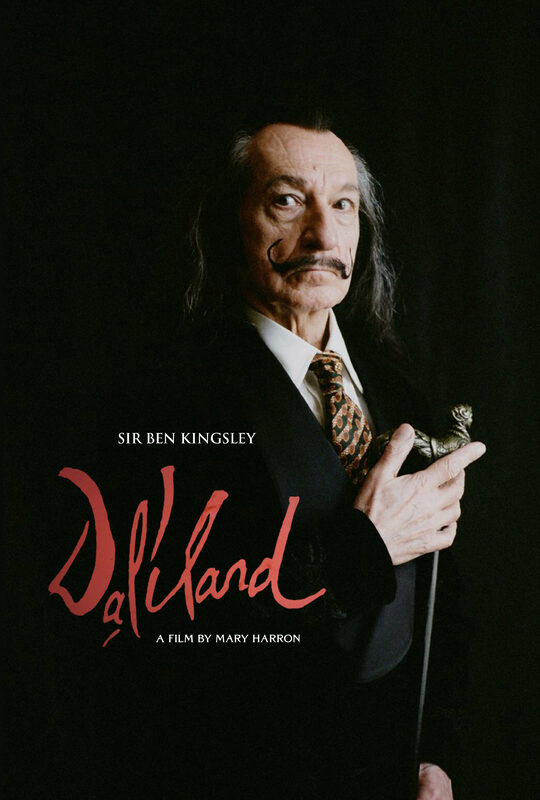

Director Mary Harron depicts the poetic decline of the master of Surrealism through the cinematic medium. Her film, Dalíland, had its world premiere at the 2022 Toronto International Film Festival.

We meet Salvador Dalí, played by Sir Ben Kingsley, at the height his career as he entertains himself with extravagant parties whilst keeping up with the prolific artistic production that is expected from him. The screenplay by Harron and John Walsh leads us into the life of the legendary artist through the naïve gaze of a young aspiring gallery owner: James (Christopher Briney).

The film opens in 1985 with black and white footage playing on a television set: it’s the Fifties’ game show What’s My Line?, where blind-folded contestants ask questions to find out the line of work of the celebrity guest. Needless to say that a hint at the iconic moustache will allow a woman to make the right guess. James is watching the show. The film then cuts to the early Seventies, when he was a gofer at the Dufresne Gallery, and was tasked with making a special delivery at New York’s St. Regis Hotel.

From that moment on, the young man will find himself catapulted into the outlandish world of Salvador Dalí, populated by a variety of histrionic individuals. There are his collaborators Captain Moore (Rupert Graves) and Christoffe (Alexander Beyer); his domineering and libertine wife Gala (Barbara Sukowa); his muse Amanda Lear (Andreja Pejić); and a bevy of young attractive girls that include the charming Ginesta-Lucy (Suki Waterhouse), with whom James will have a brief affair.

As soon as James sets foot in “Dalíland” he is swept into a whirlwind of feasts, exhibitions, shady money businesses and inspirational torments, all of this while witnessing the decadence of the artist he considers a deity.

The twilight zone of this experiential journey is the way the elderly Dalí takes a glimpse into his past, in the company of James. They resemble two time travellers who enter fragments of memories that go back to the Twenties, portraying young Salvador Dalí (Ezra Miller) and young Gala Dalí (Avital Lvova).

Several films tried to capture the eccentric life of the Spanish genius, from the 1986 documentary by Adam Low, to the 1990 biopic by Antonio Ribas with Lorenzo Quinn in the role of Dalí, amongst several others. Dalíland succeeds in bringing back to life the Surrealist artist with exceptional realism thanks to the English leading actor, who received various accolades throughout his career including an Academy Award, a Grammy Award, and two Golden Globe Awards. Ben Kingsley goes beyond the myth of Salvador Dalí, he shows the man with his physical frailties and psychological insecurities. The most elegiac moment of his performance as Dalí, is when he directs the wind on top of a cliff.

Despite the looming presence of the Catalan artist, James is the actual protagonist of the film. We observe his coming-of-age in the quirky, and at times fraudulent, art market. Nevertheless Dalí, who takes him under his wing and calls him Saint Sebastian like the martyr depicted by Gustave Moreau, has always an enriching influence on the young art admirer. In the midst of the uncanny larger-than-life events, Dalí reminds James how “progress of humanity depends on us.”

Harron does not forget to sprinkle Dalíland with some of the most distinguished highlights of the artist’s life, like that he was friends with filmmaker Luis Buñuel (they worked together on the film Un Chien Andalou) and that Disney asked him to work together (in 1945 they started collaborating on the short animation Destino, that was eventually released in 2003).

The most original trait of how John Walsh and Mary Harron have penned the encounter between an art lover from Idaho and an internationally acclaimed living legend is their mutual understanding. James is fascinated by the way Dalí changes signature every time, almost as if he were reshaping his identity through every new work. Some claim Dalí likes to “cretinise the world,” but the idealistic James sees this as part of the artist’s unceasing creative process: it requires continuous transformation.

The artist also feels comfortable confiding in the young American man: he shares his sense of inadequacy when comparing himself to masters like Johannes Vermeer and Diego Velázquez. At the same time he boldly shares insight on what triggers inspiration: it is a youthful mistake to believe it emerges from quite and peace, all great ideas start from anger.

The beauty of Harron’s take on the great Salvador Dalí is how every character sees him not just as a public figure but as an abstraction, as Variety effectively describes: “He’s not just a person; he’s a concept.” Dalí seems to be asexual in his life practices, albeit being a Peeping Tom when others have intercourse, but he uses female derrières for his body art and portrays male genitalia. He enjoys being a whimsical provocateur.

Dalíland brings to the silver screen the flamboyant personality that made the Figueres-born artist known all over the globe. The inventive rendering of his dreams and hallucinations become the means for a psychoanalytical quest, where the withering genius accompanies a burgeoning talent on a path of self-creation.

Final Grade: B