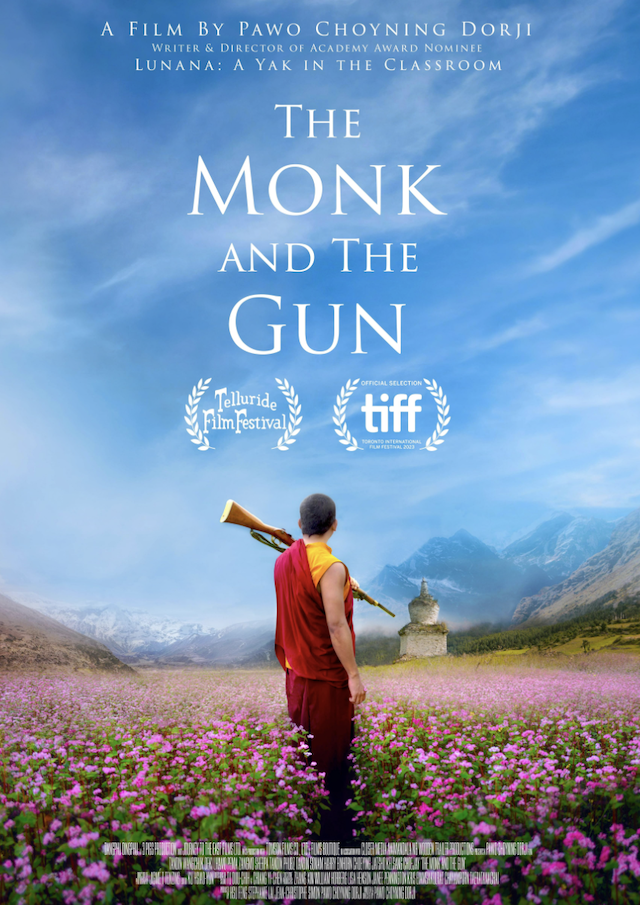

©Courtesy of Roadside Attractions

The Monk And the Gun captures the wonder and disruption as Bhutan becomes one of the world’s youngest democracies. Known throughout the world for its extraordinary beauty and its emphasis on Gross National Happiness, the remote Himalayan Kingdom of Bhutan was the last nation to connect to the internet and television. And if that weren’t enough change, the King announced shortly afterwards that he would cede his power to the people via their vote and a new form of government: Democracy.

Rating: PG-13

Genre: Drama

Original Language: English

Director: Pawo Choyning Dorji

Producer: Jean-Christophe Simon, Feng Hsu, Stephanie Lai, Pawo Choyning Dorji

Writer: Pawo Choyning Dorji

Release Date (Theaters): Limited

Box Office (Gross USA): $52.9K

Runtime:

Distributor: Roadside Attractions

Production Co: Journey to The East Films, Wooden Trailer Productions, An Amandala Production, N8 Studios, Tomson Films, Dangphu Dingphu: A 3 Pigs Production, The Jim Henson Company, Films Boutique, Closer Media, Visions Sud Est, CNC Aide aux cinémas du monde – Institut Français

©Pawo Choyning Dorji behind the scenes of The Monk and the Gun

Exclusive Interview with Writer/Director/Producer Pawo Choyning Dorji

Q: You were born in Darjeeling India. How did you get interested in this subject matter in Bhutan? What’s your relation to Bhutan that led you to make this film?

Pawo Choyning Dorji: Yes, I was born in Darjeeling India, but I also grew up all over the world. So I had an interesting upbringing. My family… We were very traditional on the one hand but on the other, we also traveled the world. I think that puts me in a very unique position to be able to tell Bhutanese stories [with a fresh perspective].

I always tell people that there’s a saying in Bhutan that says, we can’t see our own eyelashes because they are so close to us. My upbringing, being born in Darjeeling and growing up around the world, put me in a position both as a Bhutanese, but yet also an outsider to see my own eyelashes. I think that’s important. You have to be objective if you want to tell a story of your own country.

Q: When you think about the democracy in the United States, it always comes with the second amendment, where “You have the right to bear arms.” It’s intriguing that you used this title, “the Monk and the Gun.” Talk about choosing that title.

Pawo Choyning Dorji: When I made my first film, “A Yak in the Classroom,” I had no distributors, no producer and no agents attached to it. I was an unknown filmmaker from an unknown country. I wondered, “How would I be able to draw people in to watch the film?” Then, the title hit me and I was like, “Well, what if I made the film’s title, “A Yak in the Classroom?”

That’s what this movie was about. I thought if I named the film that, common cinema goers would look at that poster and be like,”What the hell is a yak in the classroom?” They’d probably be intrigued enough to go and watch it — and it worked. It went from being this unknown film to becoming an Oscar nominee.

I wanted to continue the trend with this film as well. I thought “The Monk and the Gun” really captures the essence of the story. You have the tradition, the modernization, the monk and the gun; you have the past and the future coming together. It’s an intriguing title that will make people look twice. As a budding filmmaker, I still wanted to have that intriguing title.

Q: In Bhutan, there’s obviously isolationism. They joined the United Nations in 1971 and the government started to check on this Gross National Happiness quotient; they have one of the highest rates of any country. Is it your view that people in Bhutan prioritize mental happiness over material happiness?When you think about this, how the mindset works in Bhutan, it’s particularly intriguing that, in 2022, the country opened up more for tourism.

Pawo Choyning Dorji: Bhutan is so unique. We are the world’s only Vajrayana Buddhist country in the world. We adopted this policy of isolationism, not because we wanted to, but [because] we realized that we had to do it in order to safeguard who we are. You have to understand how the Himalayan region was in the early 1900s.

There were many Vajrayana countries back then. There was a country called Tibet and one called Sikkim. But in the 1940s, Tibet became part of China and the other became part of India. We became the only country that was left. So how do we safeguard who we are? We basically cut ourselves off from the world outside because we felt like we would lose who we are. We isolated ourselves to protect who we are. We adopted the Buddhist path for achieving happiness.

But, you have to understand, when we Bhutanese talk about happiness, it’s very different from what the rest of the world talks about. Bhutanese happiness is based on contentment, but not in the worldly sense. For example, to be happy is to be very rich but in Bhutan, it’s not that. To be happy In Bhutan is to be content with what you have. To be happy is to accept the law of impermanence — that nothing lasts forever.

The Bhutanese and the government, base their happiness on the Buddha’s teaching of interdependence. We believe that we live in a world where the happiness of the self can only be achieved if all the causes and conditions around us manifest happiness. Because of that, we have very, very strange laws. People outside of Bhutan find them strange. We are in the Himalayas. Countries like Nepal, India, and Pakistan make hundreds of thousands of dollars letting people climb their highest mountain. But in Bhutan, mountain climbing is illegal! We are home to the world’s last remaining virgin mountain peaks. Those mountains have never been climbed by man before.

We do that because we believe in keeping our environment clean and pristine. We believe that [doing so] would relate to self-happiness. You’re talking about amendments in the Bhutanese constitution. One of the opening amendments is that our country has to have 65% forest coverage; we have to let the trees grow. Right now, we are hovering at around 72%. We are the only country in the world that’s carbon-negative.

These are things I’m very proud of. But it is at the end. In reality, Bhutan is a struggling poor country. We are a less developed nation. We are a third world country and, unfortunately, it’s very difficult being a country aspiring to be happy in a world that dictates that happiness [is determined] by how rich you are.

I take much pride in saying I come from a country that pursues happiness and places happiness above all else. But we have problems too, because [Bhutan] marches to a different beat in a world that dictates [what] happiness is. Now we have TV and the internet, so we know what the rest of the world is doing.

Because of that, there are economic problems in Bhutan. There’s unemployment and depression. Right now, we’re going through a movement where a huge part of the Bhutanese population is migrating elsewhere because they feel their happiness will be achieved in foreign countries like Australia, in America and Europe. I touched upon migration in my first film.

©Tandin Wangchuk and Tandin Sonam in The Monk and the Gun Courtesy of Roadside Attractions

Q: People really admire the way the Bhutanese people live. When it comes to actually being happy, you don’t have to be greedy. People live there in a way that’s been preserved for a long time. How are people dealing with materialism and do they support it?

Pawo Choyning Dorji: When Bhutan first opened up and started modernizing, people were very reluctant to change. One of the reasons why I wanted to make this film is that I grew up in the West. I went to college in the US and studied political science. Unfortunately, in the modern world, people seem to think that, “Oh, just because we celebrate and venerate democracy, the rest of the world should also be a democracy.”

Anytime where there’s one person ruling over a country, the modern world is quick to tag that person a dictator. Well, that’s not the case. There are many places in the world where people don’t want democracy; they want their king to rule over them because he has done so much good for them. I wanted to share that with the world.

When Bhutan did modernize and opened up to the rest of the world, yes, there was a lot of resistance. You have to understand that the Bhutanese people did not change because they wanted to. They changed because they realized that the modern world had left them behind. We were the last country to allow television and the internet.

Imagine how society was prior to that. I lived there. I know how it was growing up without television or the internet. And I know how it changed. I always tell people that this film is about innocence. For a culture that celebrates innocence to suddenly change and be tagged not as being innocent, but to be considered ignorant by the modern world, that’s something else.

Q: So true. Talk about filmmaking. How did you gather a film crew together? They didn’t have a film production process there already.

Pawo Choyning Dorji: No, most of my crew members were working on a film set for the first time and most of my cast were acting for the first time as well. As a director, I had to have a lot of patience. There has to be an understanding of looking at the bigger picture. Sometimes what you think is not working, what could be a disadvantage can actually be an advantage.

So yes, I lacked the professionalism [element] of filmmaking, but when you work in a place like Bhutan and have that enthusiasm, you have that authenticity and passion that [builds] camaraderie among the people and villagers. I think that really pushes the film through. You can see that there would be technicalities where you feel like, “Ah, this film is lacking there.” But overall, it’s a film with a lot of heart. The people who made it, the crew, the cast and the villagers — everyone involved in it — put in a lot of heart.

©Kelsang Choejey, Pema Zangpo Sherpa, Tandin Wangchuk and Tandin Sonam in The Monk and the Gun Courtesy of Roadside Attractions

Q: Speaking of heart, this film won the IMDB audience choice award. Out of all the American films, they chose to give your film the Audience Choice award. That’s quite an achievement.

Pawo Choyning Dorji: I’m very happy to say that both my films “Lunana: A Yak in the Classroom” and “The Monk and The Gun” seem to really connect well with audiences. I think that is very beautiful because at the end, why do we make films? Do we make them for select jury members to recognize [them]?

Or do we make films for the audience to recognize? Of course, jury awards are great, but then the audience choice… I think that’s amazing because, in order for artists to create, the artist has to be recognized by the audience. The audience gives the artist the support and the inspiration to create more. It would be very depressing if the artist keeps creating and there’s no audience recognition in it.

Q: There’s a challenge in writing this script because you don’t make a stand about either side.

Pawo Choyning Dorji: Actually, that was something I really wanted to be careful about. When I was writing the script, I was very worried because when you make a movie that dabbles in politics, you either fall into one camp or the other end. I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to just tell a story of change, a story of innocence and the loss of innocence. I didn’t want people to be like, “Oh, he’s anti-democracy, anti-monarchy or he’s anti-gun.” I didn’t want people to say that.

I had to be very meticulous in the way that I wrote the script. In the end, I feel the film has achieved that because the film has been championed by Michael Moore, who is one of its biggest liberal champions. When the film screened at the Telluride Film Festival, there were a lot of NRA members who had watched the film and actually liked it. It’s interesting because both the NRA members and Michael Moore said the same thing, that is this film teaches us Americans more about ourselves without being a story about America. I think that is important [chuckles].