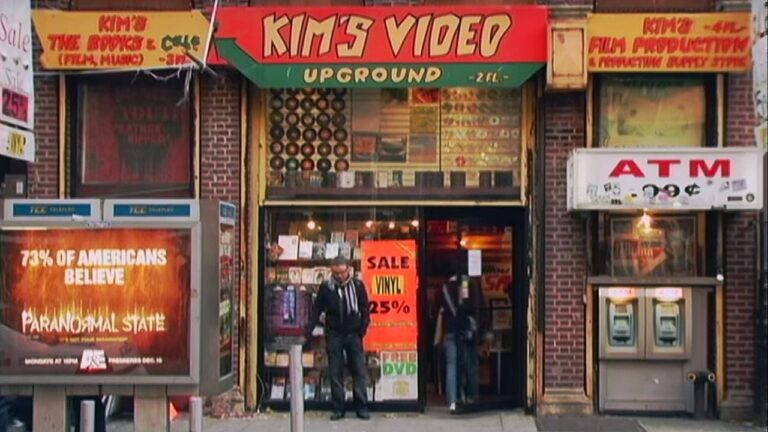

For two decades, cinema lovers of the Big Apple found their Mecca in St Mark’s Place, in the treasure trove of rare motion pictures known as Kim’s Video. This rental shop amassed 55,000 titles, but in 2008 with the advent of the digital era people no longer rented videos and the destiny of this venerable collection crossed the ocean and several vicissitudes before finding its place in the sun.

Directed by David Redmon and Ashley Sabin, Kim’s Video is an extraordinary documentary that starts as a traditional historical account and gradually morphs into an investigative thriller; it contains elements of dramedy and an idyllic inner monologue of its narrator. David Redmon grew up in Paris, Texas, the place that inspired Wim Wenders’ movie, and we see some footage of that motion picture, just as plenty more extracts of a variety of films that accompany the filmmaker’s stream of consciousness. The film director provides his full family background, growing up with his grandparents, watching movies at night, and working at Walmart as an adolescent to be able to have access to films. His life changing event was moving to New York and discovering Kim’s Video store; he claims “I found my new home,” and it is surely one he would protect through the course of time and his documentary proves it.

Yongman Kim arrived in the United States as a 21-year-old Korean immigrant and started out in the dry-cleaning business. His love for film lead him to set up his iconic video shop. He also made a film in 2006 called 1/3 (One Third), loosely inspired by Dante’s Inferno, portraying a teen prostitute as seen through the eyes of her neighbour, a Buddhist monk. The first film he had seen was a Charlie Chaplin 16mm picture, which got him hooked to the realm of moving pictures. Redmon makes a parallel between Yongman Kim and Charles Foster Kane: immigrants who arrived in New York and created empires and whose lives ultimately would reflect on what objects are significant to keep. Needless to say that Kim’s collection is the Rosebud of our story.

As the physicality of film was supplanted by digitalisation, Mr. Kim decided to donate his majestic collection to the city of Salemi in Sicily. The township wanted to revitalise its tourism, and promised to digitalise the collection and make it accessible to the public. But this is not in the least what happened. David Redmon travelled with his crew to the Italian city, to discover how all the material had been stacked in a damp building, left to deteriorate, and forgotten by all. Thus, the documentary acquires an investigative approach worthy of the best Mafia films, nuanced with comedy and artistic poetry.

We discover Kim’s collection arrived in Salemi in 2009 with great pomp. At the time Vittorio Sgarbi was mayor of the town. Italians are well acquainted with this histrionic character who is primarily an art critic, as well as a politician and a flamboyant television personality. He is well known for his episodes of verbal belligerence, the most recent being in 2020 when he was carried out of parliament by his arms and legs, after yelling abuse at fellow parliamentarians. Recently he has also been placed under investigation for laundering stolen goods.

A reflection made by filmmaker David Redmon struck me. At one point he says “Life isn’t like the movies. It’s even more strange.” I experienced it while viewing his documentary. I’ve been a journalist all my life, film critic above all, and also had the chance to dip my toes in investigative journalism joining the team of the docuseries Murder of God’s Banker. Never in my wildest imagination did I envision me watching a film, that I had to review and see myself featured in it, furthermore in an ambiguous way. I’m from Milan and have crossed paths with Vittorio Sgarbi twice in my life. Once when exhibiting my artwork in a group show where he came on opening night, and a second time when I had to interview him about an exhibition he had curated in 2017.

In this latter occasion, his assistant asked me to meet them at Teatro Manzoni, where Sgarbi was holding a conference-performance about Michelangelo. While watching Kim’s Video I observe the footage concerning Sgarbi and memories of that time run through my mind. I recall his assistant Paola putting socks on him in the dressing room and I hear the filmmaker’s voiceover describing Vittorio Sgarbi’s entourage…exactly when I see myself walking next to him. I have a look of dismay, since all of us journalists had been kept waiting for over an hour. It’s the same expression

I have while watching Kim’s Video, and seeing myself erroneously identified as part of his staff. This leaves me with a broader reflection on how anything taken out of context can be misleading, but I’m thankful to David Redmon for stirring this sense of restlessness in me. I gradually acknowledge my insignificance in the wider picture and I am grateful for my anonymity that will make me an unnoticeable element of the narrative. Above all I get to the end of the film having transformed that feeling of self-absorption into incommensurable admiration for the filmmaker’s plot twist, that shows his utter love for Mr. Kim’s collection. I no longer identify myself with a misrepresented character, but with those I feel most akin to: the heroes who save the day in the name of cinema.

The Centro Kim — i.e. the project involving the digitalisation of all of Kim’s videos — in 2008 was granted a sum of 800 thousand euros that had to finance the entire operation. Only 30 thousand euros were spent without producing anything. Leopoldo Falco was at the helm of the Anti-Mafia commission investigating in the infiltrations of organised crime in Salemi and brought to attention how Giuseppe Giammarinaro was accused of being involved with the Mafia. He claimed with certainty: “the investigation and police wire tapping showed that Giammarinaro presided within Sgarbi’s council. He had no title or authority to do so.” Basically Falco was stating that Sgarbi allowed the Mafia to infiltrate in his administration. Falco died unexpectedly in his sleep before the investigation was completed and all charges to Giammarinaro were dropped. Later on Sgarbi was removed from his role and the administration of the city was commissioned after he failed to acknowledge Sicilian Mafia interferences in his cabinet.

Meanwhile, Redmon and his team try to find Yongman Kim, who initially is difficult to track down. They finally manage to meet him in Seoul and will follow Mr. Kim when he returns to Salemi 10 years after his collection was brought to Sicily. Mr. Kim tells the new mayor, Domenico Venuti, that the agreement on the preservation of the collection miserably failed, but the conversation is met by indifference. The same effect is produced when Vittorio Sgarbi pays another visit to Salemi, with Giammarinaro, and Redmon tries to get them to visit the degraded collection.

When all hope is lost, once again, cinema shows the way. David Redmon, having returned to New York City, serendipitously sees the footage of the 1976 Irritation—There is a Criminal Touch to Art. It captures Ulay’s theft from the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin of Hitler’s favourite painting, that he then donated to a Turkish family as a political act. Redmon has an epiphany while watching a heist become a form of activism in favour of cultural preservation. With his crew, the American filmmaker returns to Salemi during Carnival season asking to shoot a fictional film inside the Centro Kim.

What happens next leads to the best of happy endings, thanks to the bravery and idealism of a group of cinephiles supported by the disguises of the most notable cineastes in history. Maya Deren, Jim Jarmusch, Charlie Chaplin, Alfred Hitchcock, Jean-Luc Godard and Agnès Varda are just a few of the filmmakers who join the fairytale quest to save Kim’s collection and bring it to a place where it finds the care and recognition it deserves. The promised land and new home of the legendary collection is called Alamo Drafthouse. The villains of the story remain unscathed, and actually find a way to gain something out of the entire operation, unconcerned it may affect their reputation.

As Redmon says “Cinema is a record of existence, it retains traces of lives lived.” It indeed represents our collective memory and Kim’s Video is an admirable testimony of the power of cinema and the wonders it can work through those who genuinely love it.

Final Grade: A