©Janus Film

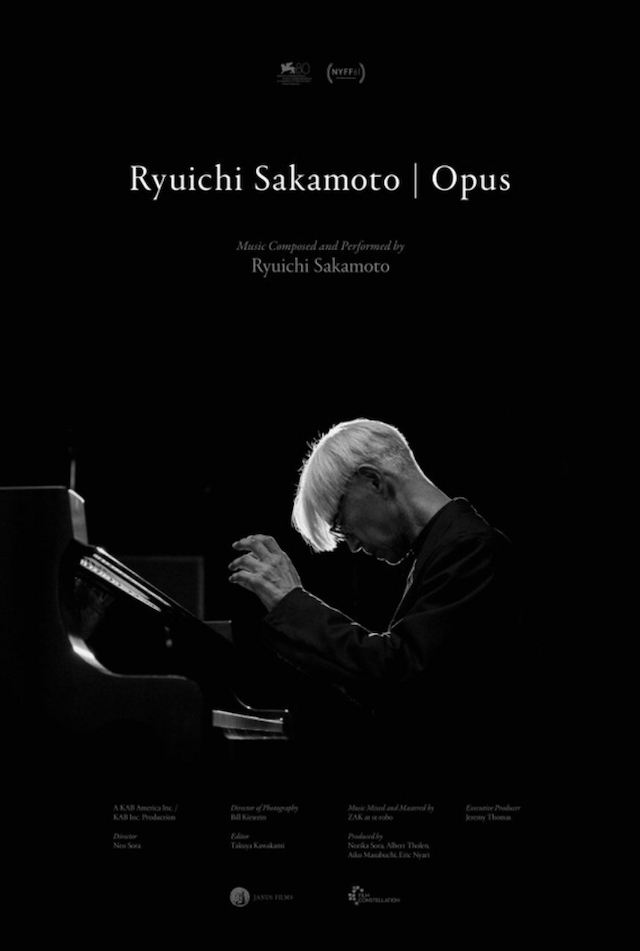

Ryuichi Sakamoto : Opus /A celebration of an artist’s life in the purest sense, the film is the definitive swan song of one of the world’s greatest musicians. In late 2022, as a parting gift, Ryuichi Sakamoto mustered all of his energy to leave us with one final performance: a concert film featuring just him and his piano. Curated and sequenced by Sakamoto himself, the twenty pieces featured in the film wordlessly narrate his life through his wide-ranging oeuvre.

The selection spans his entire career, from his pop-star period with Yellow Magic Orchestra and his magnificent scores for filmmaker Bernardo Bertolucci to his meditative final album,12. Intimately filmed in a space he knew well and surrounded by his most trusted collaborators, including director Neo Sora, his son, Sakamoto bares his soul through his exquisitely haunting melodies, knowing this was the last time he would be able to present his art.

Genre: Documentary, Music, Biography

Original Language: Japanese

Director: Neo Sora

Producer: Norika Sky-Sora, Albert Tholen, Eric Nyari, Aiko Masubuchi, Jeremy ThomasA

Release Date (Theaters): Limited

Runtime:

Distributor: Janus Films

Production Co: Bitters End, KAB America

©Janus Film

©Janus Film

Q&A with Director Neo Sora

Q: Can you explain how this film found its initial footing and how that defined the form that it took?

Neo Sora: I’ve been calling this a concert film preemptively because it gets billed as a documentary a lot, but, it doesn’t really have a story in a traditional sense, and neither does it have many hooks to give you access to who he was as a person other than just seeing him perform. I definitely do think it has a story, and I think it’s told by the music and his expressions, which I feel was communicated to you, so, thank you.

Basically it started because he was ill, but he wanted to do some kind of a concert project before he passed. And the most recent one before this was in 2020 in December, which was an online live streamed concert that had a digital component to it. It was filmed in a green screen studio, and had a digital environment where he was playing it. There were some technical things that didn’t really work out with it, and I think he and his team wanted to do one more thing.

But he was getting too ill to really do live concerts. He was taking medication, which was affecting his fingers and extremities a bit; he was definitely in pain. His stamina was much lower, so they reached out to me, basically, and said, “Hey, can you do something? Do you want to do some kind of concert film project?” So, basically it was his idea. He wanted to do a concert, and the kind of medium that was available to him, was also the medium that I had to be working in — film — so it all came together in that way.

Q: It was always just going to be him and the piano?

Neo Sora: Yeah. In terms of the music element of it, I would say there was definitely a professional separation between me and him in terms of what we were responsible for. He was fully responsible for what he wanted to do and the music, and then he told me what he wanted to do, and I was asked to craft something out of that. The fact that it’s just him and piano, the 20 songs that he chose, the studio that we recorded in, all of it was his choice, although there was a bit of collaboration in that.

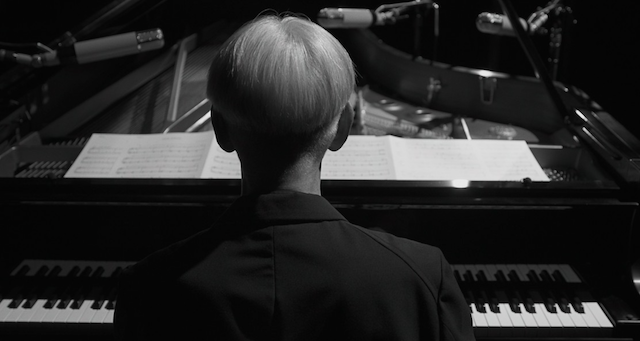

Once I came up with the concept of shooting, designing the lighting so that it was expressed like the passage of time from night to day to back to night again, he rearranged some of the songs to fit the atmosphere of the morning or nighttime —things like that. But largely all of this stuff was his choice, and I think it definitely only gives one aspect of his personality and also music, because he definitely experimented a lot with synthesizers and other kinds of sounds as well. But I think the piano was something really foundational to him.

Q: Can you say a bit about where the studio is and what significance maybe it held for him?

Neo Sora: The studio is called 509 Studios in NHK, which is like the national broadcaster of Japan, and it was pretty difficult to work in because it had a lot of regulations surrounding radio signals; they broadcast radio from there as well. So we weren’t allowed to use any wireless technology, which was a really big problem for the filmmaking.

Basically all three cameras were wired, and the kind of technology usually on film sets these days, everything is wireless. Video is sent wirelessly, all these things are wireless. The lavalier microphones are wireless, but all that stuff is all wired. We also had a lot of wire wranglers wearing socks to be very quiet during the filming. But it was a studio that he really liked and enjoyed. I think he did some kind of TV show there. I don’t exactly know what he did in the past, but he definitely worked in that studio before, and he said that to him, it was the best sounding studio in Japan.

Q: You mentioned the crew wearing socks, but your film also does highlight or draw attention to the imperfections of the performance. There’s the starting and stopping, there’s the break that he mentions needing. At what point did you settle on including these aspects in the film?

Neo Sora: In preparation for the film, I listened to him and even recorded, with an iPhone, him practicing on his piano. I noticed that there were definitely certain songs that were very difficult for him to play, and he would just repeat certain phrases over and over again, because he would always miss a note here or there. Watching that also told a story. I think my overall goal for the film was to shoot him in a dignified way as a performer, but there was also something that really drew me to the kind of drama of the story, of somebody who was ailing, trying his best to play. When he makes these small mistakes or is practicing a little bit more, I decided to bring those in, because they’re kind of a glimpse into that aspect of his story.

There’s one song, called “Bibonaz,” where he stops playing for a second and then continues and starts exploring these harmonies. I think that, for me, really shows a kind of side of a composer, a musician, that you don’t necessarily get to see that often in concert, where everything is practiced and rehearsed. That’s kind of what it’s like when he’s figuring out new music. The mistake that he makes and, then, his decision to continue playing, even though he’s made a mistake. It kind of frees him to explore these chords that I think, otherwise, he wouldn’t have done. I thought that was an interesting glimpse into the process of a musician’s mind.

©Janus Film

©Janus Film

Q: You mentioned the passage of time forming the structure of the film, going from night to day to night again. Talk about that, in terms of working with your cinematographer, Bill Kirstein, and how you both were thinking of defining the visual language of each track?

Neo Sora: What we were trying to do was to create some kind of through-line in the film so that it’s not just a static-feeling concert where nothing really changes except for the music. He himself was really interested in the concept of time, and how people and different beings experience time; that was a really important inspiration for coming up with the lighting pattern. I guess the most important thing was to be responsive to the music and try to express the subjectivity of somebody attending a concert.

If the film was designed to be a concert with an audience and multiple cameras shooting him, there’s only a certain closeness that you can get. Because we were afforded the privilege of putting the cameras wherever we wanted, we tried to mimic the subjective experience of a concert-goer who gets pulled into the music as the performer begins to play. That’s why we used a lot of dolly moves and things like that. The most important thing was definitely to be responsive to the music itself, and that’s how we designed all the shots and cinematography.

Q: Did you always know you wanted to shoot in black and white?

Neo Sora: It was a question during pre-production, but there was definitely one day when we decided we would do it in black and white. That actually opened up a lot of possibilities for us as well. It wasn’t a thing from the get-go, but once we decided on it, it really brought everything together.

Q: Was there any kind of research that you conducted in the lead-up? Were you watching or thinking about other concert films?

Neo Sora: The big one that I watched over and over again was this really amazing concert made for TV that Ford produced, where Leonard Bernstein and Glenn Gould were performing together. The cinematography for that was really stunning, and the lighting for that as well. It’s on YouTube. Go check it out. It’s really great. I was watching some other Glenn Gould-related films. There’s one called “Thirty Two Short Films about Glenn Gould,” and there were some really amazing sequences in that; we tried to incorporate a little bit of that as well.

But otherwise, the black and white really helped me think about the kind of pure visual pleasure of shapes moving on screen, accompanied by music and rhythm. That is something which, for me, spoke a little bit to the days of experimental films like “Ballet Mécanique” and things like that. That’s one of the reasons we decided to go really up close in certain moments, so that it really feels like just abstract shapes on screen as they move to the music. It kind of tingles the eye.

Q: How long did the shoot take?

Neo Sora: It was about eight or nine days.

Q: Can you recall what the energy was like on set? On day one, how was Sakamoto feeling going into this? A few of the arrangements were heard on piano before, while some of it has been significantly changed; his performance presented a slower version. How did that change over the course of the shoot?

Neo Sora: It was really tense. There was a productive kind of nervousness in the air, I would say, because you can only really capture one good performance and, in terms of the filmmaking side of it, we all had to be really in tip-top shape. We would rehearse a bunch with a stand-in. Then we’d listen to the recorded music over and over again to try to nail some of the camera movements and stuff like that.

But as soon as he walked on stage and started playing, there was definitely this kind of tension in the air. On the first day, he was really energetic, and we were able to do, like, five songs. We were only planning on three. But then as the days went on, he could only do, like, three then two songs per day. I think with each good take of the song, it really took it out of him, especially the really emotive songs.

That was where he put a lot of effort into playing. I think the way that he would get really tired after playing, like, “Wuthering Heights,” for example. I imagine it was like having a good cry. It was very emotional, and really exhausting afterwards. I can definitely see how tired he was getting, for sure. That made us, on the filmmaking side, to really make sure we were on top of our game.

©Janus Film

©Janus Film

Q: What was the burning question that you had that you didn’t get to resolve?

Neo Sora: A burning question? I don’t know if I had a burning question. My main intention was to try to be a conduit of whatever he wanted to do, and to do it well. I didn’t really have too much of an intention or a question that I needed to solve or resolve in the film. I just really wanted to do a good job so that he could express whatever he wanted to express.

But I think afterwards, while editing the film, there were definitely a lot of things that I realized that I couldn’t necessarily articulate before making the film. Something that I really thought about during the editing of the film was how he oscillated between two poles of contradiction.

He had a big contradiction within him. On one hand, he’s really intellectual and thinks about music forms in a really intelligent way, which he experiments with, and sometimes his music is all about that. On the other hand, I think he can be really sappy, sentimental, melodramatic and very emotional. All of his music has a little bit of both in it. To me, the best songs are a perfect fusion of the two poles. He was always wrestling with that dynamic.

I think there’s always a limiting factor whenever he tries to get a little bit too emotional. There’s always a little voice in his head that says, “No, no, that’s too cheesy. We have to keep it interesting. We have to make the harmony more complex or whatever. I think the one song that he really lets go of is “Wuthering Heights,” actually. He really goes for the melodrama. And, the more I watched it, the more I thought that that was really unique about the song, and about how he plays it as well. There were those kinds of things that I realized, but I don’t think I really have further questions or anything like that.

Q: There’s a question about black and white being a kind of metaphorical device between this tension that you’re talking about…

Neo Sora: I don’t know if black and white was necessarily that, although I can definitely see how it can be read into it that way. But for me, the moments where I really noticed that tension within him was when the camera was really close up and I could really see his expression.

Q: Was there any other dialogue that was cut, on the editing floor [so to speak] that might have given an extra peek into his life that you mentioned earlier with those three phrases?

Neo Sora: The line of dialogue that I had in there that was rejected by his management — it was of the person who was in charge calling action; he was saying it in a weird way, and there was one take where you can hear a guy calling action… How did he say it? He would say, “A-shun!” Or something like that. Then there was a take where he was about to play, and then the guy said, “A-shun, ” and then he was like, “No, it’s Action! Action! Emphasis on the A.”

And then the guy’s like, “I apologize.” He’s like, “No, no, no, action!” I had that in because I thought that it was funny. He can be a pretty funny guy sometimes. In real concerts, whenever he’d emcee, he would always try to crack jokes, and some of them were pretty not funny, but then other times, they were. And yeah, he’s a funny guy. I wanted to keep that in, because I thought that it showed that [about him], but it was cut.

©Janus Film

Q Among those pieces, what is your favorite, which piece would you pick as the same song for this movie?

Neo Sora: I said that we had a professional separation in terms of the music and the film, but actually there was one infringement that I made, which was to ask for the final song of the film to be “Opus.” Originally he was either going to make the final song “Happy End,” which is the second to last, or third to last song here, but there was something about I, for me. I really like his pieces and songs where the feeling of it is really unaffected and non-emotional, a kind of quotidian statement.

In the fifth or sixth song of this concert, it’s called “Obeyed 2020,” and that is one of my favorite songs because of how repetitive and unaffected it is. In the grand scope of things, it speaks to the feeling of the days going on. For me also, “Opus,” the final song, has that quality, so I suggested, what about “Obeyed” or “Opus” for the final song, and he liked that idea. Then he chose “Opus,” but also arranged it in a slightly different way so that it’s shorter.

He was also telling me that he tried to play “Opus” in as unaffected of a way as possible, We were talking about it in terms of [the late director Yasujirô] Ozu a little bit, how Ozu has this very steady tempo and pace; his dialogue is fairly unaffected for the most part, and the shots are very static, but still really moving. To me, and to him a bit, “Opus” and “Obeyed” have those kinds of feelings. That, to me, was almost more emotional than if it were an emotional song, so I really liked that.

Q: Could you talk about his collaboration with Hirokazu Koreda? That was his last composing work. Because of his illness, he couldn’t score the entire film so he chose two songs to compose for it. What was his process in creating songs for Koreda-san?

Neo Sora: I’m sorry to disappoint you, but I haven’t seen the movie, and don’t really know what his process was for that. You might know more than me.

Q: When he smiles, the way you capture it with the lighting, was that something that just happened or did you plan that throughout?

Neo Sora: Thank you, but no, nothing was planned in that way. All of his expressions, all that stuff, is the documentary aspect. We definitely planned the shots and made sure that his expression and physicality were the things that the camera operators were focusing on, but the faces he’s making and emotions that are on display are definitely just there. It’s happening but in the edit, we made sure that you don’t miss those moments. We made sure to put them in.

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.