©Courtesy of Tribeca Festival

Assigning the responsibility to shape the evolution and future of an already built environment in a thriving, bustling city has long served as an existential crisis. The way people work within – and outside of – existing systems to try to strengthen and protect a specific neighborhood is the driving force of the new political-driven documentary, Emergent City.

The film was co-directed and produced by Sunset Park community members Kelly Anderson and Jay Arthur Sterrenberg, the latter of whom also served as the project’s editor. Their latest feature chronicles the efforts of community leaders in their Brooklyn neighborhood to save the long-established soul of their home, which is juxtaposed against the desires of ambitious figures.

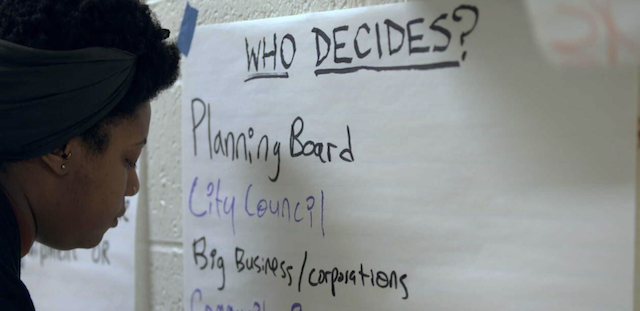

At a time when a housing crisis looms over many metro cities in the U.S., the filmmakers highlight the champions who are forging a better path forward to save their community, as contemporary urban development hangs in the balance. The movie explores the profound intersections of gentrification, climate crisis and real estate development. The filmmakers also show how change might emerge from dialogue and collective action in a world where too many outcomes are constrained by money, politics and business.

Emergent City follows a group of global developers who jump at the opportunity to buy a string of connected industrial buildings when they become available in Brooklyn. The developers have big ideas for the future of Industry City, a highly sought after and historic intermodal shipping, warehousing and manufacturing complex in the New York City borough. Nestled against the waterfront in Brooklyn’s Sunset Park neighborhood, the developers set their plans in motion.

However, the community’s working class, which primarily consists of immigrant residents, worry that they could be displaced once the development changes the space. However, others see promise in the future of a developed Industry City. As a result, mediation begins between residents, city officials and master planners in an effort to find a workable solution for all involved.

Emergent City made its World Premiere in the Spotlight Documentary section of this year’s Tribeca Festival. Anderson and Sterrenberg generously took the time to talk about helming and editing the documentary during an exclusive interview over Zoom before the feature’s premiere at the New York-based festival.

©Courtesy of Tribeca Festival

Exclusive Interview with Directors Kelly Anderson and Jay Arthur Sterrenberg

Q: You both serve as Sunset Park community members. Why do you both feel it’s so important to save the soul of your neighborhood, which is juxtaposed against the desires of ambitious figures?

Kelly Anderson: I had directed and produced a film in 2012 called My Brooklyn, which was about the development of downtown Brooklyn. It dealt with a lot of similar themes of people seeing neighborhoods change, and wanting to understand why and what the deeper forces at work were.

So at that time, I ended up leaving downtown Brooklyn because I couldn’t afford to live there anymore. I moved to Sunset Park and I got to know people here because they knew the film that I had made, as we did some community screenings.

Sunset Park is a is a great neighborhood. It’s a thriving immigrant neighborhood.

But when Industry City started to be redeveloped, I was shocked by how out of sync with the community it felt at first glance when I went down there. So that’s when I started talking to different people in the community about what was happening.

Jay and I had known each other previously, through an organization called New Day Films. We just started talking about the whole situation, including the fact that a lot of our favorite film organizations were screening there, like Rooftop Films.

So we felt conflicted. We questioned, what is this, and why are they trying to appeal to these creative professionals like us? We also wondered, what it would mean for the community, which we cared a lot about?

Jay, maybe you can pick it up from there?

Jay Arthur Sterrenberg: Sure. I’m a co-founder of an arts collective and worker cooperative production company called Meerkat Media. We’re really involved with a lot of different community organizations with local politics there.

We’ve also had our offices in Sunset Park for more than 10 years. Our first space in the neighborhood was just across the street from Industry City.

So every day going into work, we were watching how the facade would be changing. We’d also see how new restaurants would be added all the time on our Google Maps. There would be new things all the time in their food hall that would come up and be heavily promoted to us.

In those early years in Sunset Park, my collective and I made another short film that was in a observational film called Public Money. It was all about an experiment around participatory democracy that all was in Sunset Park.

Through making that film, we deepened a lot of our relationships to some of the community members that really became key in the rezoning process that we covered in Emergent City.

So I think both Kelly and I could see that, living and working in the neighborhood, that there was something out of step happening here. We really wanted to learn more. As soon as we learned that there was going to be a land use battle, it became clear that these new owners were going to not just do the redevelopment they were already doing, but also change the land use rules.

Since Kelly had done this other film all about zoning in New York, we had a sense of what that might look like. It ended up playing out in a much more dramatic way than I think we ever could have anticipated.

As we got more involved in that conversation, we became much more aware of the long-standing work that many members in the community, on the community board and in different nonprofits in the neighborhood had been doing. They had been pushing for decades to keep Sunset Park as a working industrial waterfront for many reasons that you see in the film.

I think there was a real terror among a lot of people in the neighborhood of this vast working waterfront just vanishing and transforming into higher end uses. That’s what has happened to waterfronts all over New York City.

Q: You co-directed the new documentary, Emergent City. Why did you both decide to helm a film that chronicles how the mediation begins between residents, city officials and master planners in an effort to find a workable solution for all involved?

Kelly Anderson: I would say one of the key ideas was that we didn’t want to make a film that told people what to think about the topic. We have strong feelings about all the issues in the film. But I think we wanted a film that was more observational in nature where people could grapple with the contradictions and the conflicts that were unfolding.

It was a very complex situation here; it wasn’t just a simple story of a community that was completely united against a developer whose plans were just horrendous.

I think there were like a lot of nuances here. So we were really interested in allowing audiences to have the kind of experience we had, which included us questioning, what’s going on here, what should happen and which strategy is right?

Should the community negotiate with Industry City to get this community benefits package? Should they just say no? What’s the right solution?

I think for us, taking a bit of a hands-off approach and just crafting a journey for the audience, where they could really not be overwhelmed with all the details and complexity, was beneficial. We want them to be able to grapple with all of the issues, in a meaningful way, on their own terms. I think that was the challenge, and I hope that we achieved it.

But I think that was that was a big thing – we wanted it to not be too didactic, in terms of giving people a message that we wanted them to just swallow and believe.

©Courtesy of Tribeca Festival

Q: Emergent City features such community members as Carlos Menchaca, who served as the NYC Council member representing Sunset Park; Marcela Mitaynes, who represents New York’s District 51 in the State Assembly; Antoinette Martinez, the Chair of the Housing Committee for Brooklyn Community Board 7; and Elizabeth Yeampierre, the executive director of UPROSE, Brooklyn’s oldest Latino community-based organization. How did you decide to feature in Emergent City?

Kelly Anderson: It’s interesting because we didn’t want to make a traditionally character-driven documentary, where you just really latch on to one to three people. We really didn’t want to see the whole thing through their goals and ambitions, and whether they achieve what they want or not.

We knew it was a film that was going to be about a community. Everyone in the film represents not just themselves, but a point of view, a constituency or an experience.

So I think for us, certain people just came forward as very compelling right from the get go. Then it was a question of, if there’s five people who are all involved in the same organization representing the same point of view, who do we want to feature a little bit more? You might not see them a lot, but you see them three or four times.

So Carlos Manchaka was an obvious choice because he was the council member who was tasked with making this decision. He was really squeezed between all these different agendas.

So we knew that would almost be a proxy for the audience. We also thought it would be interesting to see him grappling with all these pressures.

We met Marcela Matanz, the tenant organizer who becomes our assembly member for the 51st assembly district, early on. We really appreciated her as a person and an organizer.

She grew up in Sunset Park and was evicted by a landlord after living in her apartment for 30 years. That’s how she became a tenant organizer. So she was just somebody that we gravitated to. Similarly with Antoinette Martinez, who was part of the Protect Sunset Park group.

The same was true with Elizabeth, Pierre, who’s the executive director of UPROSE. She, aside from being very dynamic and powerful speaker and thinker, also heads UPROSE, which has a very important role in the film. Growing out of their experience in Sunset Park, she and the group deal with this toxic industrial waterfront that they want to repurpose for climate adaptation.

UPROSE had a really key role in the information presented in the film. This whole idea of moving away from extractive, toxic, industrial manufacturing, but keeping it industrial and providing jobs in the new green economy, doing climate mitigation, was so important. That was a very powerful reason why the waterfront shouldn’t turn into a retail destination or a high-tech office destination.

So I think UPROSE’s work, not only nationally, but also certainly in this region, made it obvious that Elizabeth was not only going to be in the film, but featured the way that she was.

Jay Arthur Sterrenberg: I think it was also always really important for us to include the developers as well in that, including Jim Samoa at the end. We also wanted to include Andrew Kimball throughout the process, who was the CEO of Industry City through most of this whole rezoning project.

That was very important to us, as we were developing the project and building the relationships to see this from all of these different sides at the same time.

I think part of what also drove that question of who we followed had to do with power mapping and understanding where the lovers of power are in the neighborhood. So obviously the CEO of this development has a lot of power. The council member who’s going to direct the entire city council on how they’re going to vote is also important.

Then watching the way that a number of meeting members, but especially UPROSE, which is spearheaded by Elizabeth Yeampierre, was also important. They were really thoughtful and strategic around developing and releasing this alternate plan for the waterfront. It was called the GRID, the Green Resilient Industrial District. Having that be an alternate plan that the community could be grappling with, so it wasn’t the rezoning or nothing, was an additional vision.

We tried to allow the audience to see the way that this strategy is being thought up and implemented in different ways while watching the film. So we felt the moments of working with the politicians, or resisting and creating public disturbance, was important to show.

We wanted to really show this diversity of tactics that went in from both sides, and how different groups are taking different tactics. We wanted to show that the developers are trying to encourage the community to go along with this idea, while many different members in the community were addressing this in different ways, using different tools. So that really helped us determine who we were going to follow, too.

Q: Jay, you also served as the editor on Emergent City. How did you work together to put the final version of Emergent City together?

Kelly Anderson: Well, I’ll just start by saying that we were filming since 2017, and I think there were over 200 days of shooting. One of the nice things was we could just go out and film, since we live and work in the neighborhood. So we could just go out and shoot for an hour sometimes.

But we had a ton of footage. One of the things I feel really good about is that we started from the bottom and worked our way up in a way that we really looked at everything. We then made assemblies and selects, and then made more refined select.

So it wasn’t a situation where we just dove into one scene or another scene. We just really processed everything, and we did that because we had time. Go ahead, Jay

Jay Arthur Sterrenberg: I think we spent about a year just looking at all the footage from the meetings and thinking and talking about it before we really had the other funding in place. We were figuring out what are we going to do with this.

We were also figuring out where is the story was going to end. There were still things we were filming after the pandemic and things sort of resolved.

But we spent a long time doing a first pass. We probably spent about two years – not full time –in the actual edit of the film. It was really important to us to find that mode of storytelling that worked for this.

So we probably have had 30 or 40 different versions of that first half hour of the film. We tried so many different ways to get that balance in a way that we feel hopefully is just right.

So, it was a real blessing of working with ITVS (America’s leading funder and presenter of independent documentaries). There wasn’t artificial time pressure from them. They really believed in us and encouraged us to make the film the way we wanted it to be.

We also had hours and hours of footage from the neighborhood, which we ultimately went through. We then built out the structure with all of that footage, including the meetings and the process.

Once we had that laid out, we actually went back and re-shot a lot of things in the neighborhood over the last year or so. That way it wasn’t just miscellaneous footage in the neighborhood; instead, it was like very purposefully filmed moments with people in the neighborhood. So we re-did a lot of a lot of that stuff.

Ideally nothing in the film is just a B-roll or miscellaneous, throw away shot. This has always been the hope with the film, but I think we took the time with this one. We really feel good about every shot that you’re seeing, and think they mean something and contribute to the broader understanding.

Kelly Anderson: Just to add on to that, one of the ways that we approached what might be normally considered B-roll is we actually had conversations with most of the people in the film. They might just show up for one shot, like working in a fish market or fixing somebody’s belt. But they actually had a conversation with us about what we were doing, and consented to being in the film.

A lot of times we had mics on them. Even though we are part of the neighborhood, we didn’t want to feel like we were just grabbing shots on long lenses, and people didn’t even really know they were going to be in the film.

That was something we cared a lot about. It took us a while to get to that, especially with these wide shots. If you don’t put a mic on somebody and you’re in a wide shot, it by definition feels distant and far away. But if you can suddenly hear the person talking, it’s a different experience and it feels much more intimate and that consent was given.

Q: Emergent City (had) its World Premiere in the Spotlight Documentary section at this year’s Tribeca Festival. What does it mean to you both that Emergent City (screened) at the festival?

Kelly Anderson: We’re totally thrilled. We just literally finished the film two nights (before the interview).

We brought in wonderful people to do composition, color, sound mix and design, and animation. But we didn’t have a huge team to support the post (production). So we just finished the film.

To have a New York City premiere (was) incredible. To be able to premier it in the town that the film is about, and in the real estate capital of the world in some ways – or, at least, in the U.S. – is amazing.

To be able to have so many people who are in the film or worked on the film be there and be part of the conversation is a dream come true.

We (then screened at DC/DOX Film Festival on June 15 in) Washington, D.C. (which was) amazing, too because the film is about politics and power. It’s really meaningful to us.

Jay Arthur Sterrenberg: I was joking with Kelly as we were just watching our final master of Emergent City. We did the sound, color and everything also in Brooklyn, and I realized that it (was) going to be really fun to watch the movie in Manhattan, at Tribeca. We’ve never watched the movie out of Brooklyn (before the Tribeca Festival).

So that (was) a new experience, even though it’s the hometown of the film. So we (were) really excited about that.

We’re also really looking forward to being able to do more screenings down the road in Brooklyn, particularly in Sunset Park, translated in different languages, like Chinese and Spanish. That (wasn’t) part of the first premiere screening, but we have a lot of things in motion of planning in order to bring the film home to Brooklyn.

Then, of course, bringing it outward to other places around the country and world, too, over the next, year or two, will be amazing. We’re thrilled to be sharing the film!

If you liked this article, please share your comment below.

Check out more of Karen Benardello’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.