©Courtesy of Janus Films & Sideshow

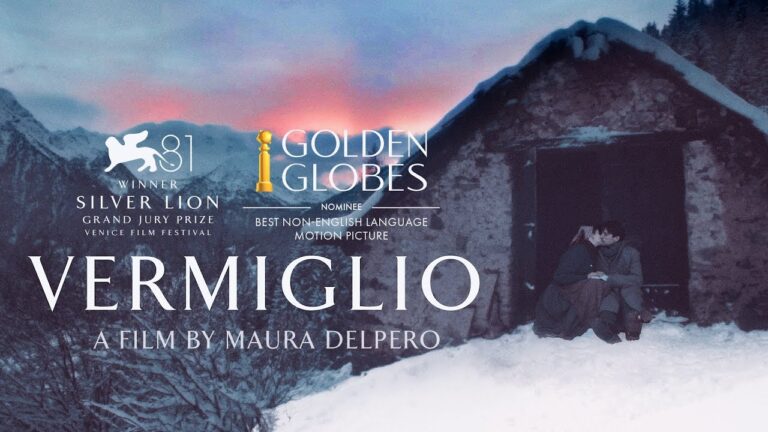

Cesare Graziadei’s sprawling household might be a little like The Waltons of 1940s Italy, but they have a sadness and perhaps even a darkness that would be alien to America’s favorite Appalachian TV family. On the surface, there is a pastoral beauty to their roughhewn life beneath the towering Italian Alps, but they endure very real hardships. Nevertheless, the Graziadei clan carries on in the face of adversity, as families do, despite the occasional heartbreak in director-screenwriter Maura Delpero’s Vermiglio, which was won the Silver Lion at the Venice International Film Festival, and also nominated for the Golden Globe, and just shortlisted for the Academy’s Best International Feature Award, ahead of its Christmas release-date.

The Graziadeis have more children than beds, so everyone must share. Of course, winters are chilly in the Italian alps, where the village of Vermiglio remains practically untouched by the modern world. None of the houses have central heating and most garments are homespun from natural fibers. Everyone must wake early, especially the eldest daughter, Lucia, who milks their cow to provide for her family’s breakfast.

Despite their crops and livestock (which are necessary for survival), Signore Graziadei’s primary occupation is that of teacher in the one-room schoolhouse serving the titular village. His position bestows considerable prestige and influence, but little in financial compensation. Nevertheless, he often vexes his (almost constantly pregnant) wife Adele by spending their limited funds on phonograph records—like Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons, which becomes a touchstone musical motif throughout the film. (However, record collectors will understand his contention music is “food for the soul.”)

©Courtesy of Janus Films & Sideshow

©Courtesy of Janus Films & Sideshow

Regardless, that is the only indulgence viewers see throughout the film, except maybe a consoling drink or a well-earned café-break. Life grinds on, so much so that the ongoing war hardly registers for the village. Whereas most Americans compulsively followed radio war reports, nobody in Vermiglio even owns a “wireless.” Consequently, they have little frame of reference when two deserters take refuge with Signore Graziadei’s sister, Cesira. For her sake, Cesira’s son Attilio and his Sicilian friend Pietro stay in her barn, to maintain his mother’s remotely plausible deniability, but their presence is an open secret within the village.

Frankly, illiterate Pietro’s Sicilian dialect sounds as foreign to Lucia as ancient Sanskrit would to us, but their romantic attraction transcends language barriers. Soon, it becomes yet another fact of life for her parents to manage.

The beauty of Vermiglio comes directly from its Spartan austerity. Every scene framed by cinematographer Mikhail Krichman looks museum-worthy, especially his snowy winterscapes, which almost suggest the influence of Flemish master Pieter Bruegel (the Elder).

However, the pace in Vermiglio passes by very differently from what contemporary viewers are accustomed to, because it is a very different world. Clearly, Delpero primarily intends to immerse viewers in this insular community, while storytelling, per se, represents an important but secondary concern. When it comes to that first goal, Delpero succeeds smashingly. However, Delpero’s severe aesthetic approach often keeps viewers emotionally at arm’s length.

©Courtesy of Janus Films & Sideshow

©Courtesy of Janus Films & Sideshow

Yet, regular film-patrons will likely not see finer ensemble work than that from Vermiglio’s cast, which features many nonprofessionals making their film debuts. Remarkably, the many young children look and act entirely as if this hardscrabble life is all they ever knew (you would hardly believe they ever saw commercially packaged food, let alone an Xbox). Likewise, Roberta Rovelli plays the long-suffering, no-nonsense Signora Adele with conviction that demands respect.

However, Tommaso Ragno’s masterful portrayal of the Graziadei patriarch will truly linger in viewers’ memories, for its quiet power and subtle complexity. Ironically, Martina Scrinzi’s Lucia appears so angelically innocent, she seems as out of place in the frosty Alps as she would in our contemporary world. Appropriately, her keenly expressive performance conveys Lucia’s deep sensitivity.

Essentially, “nothing” happens in Vermiglio, except some of the most difficult and challenging events the Graziadei family will ever face. It in no way classifies as a “war movie,” but wartime circumstances still definitely contribute, indirectly, to their troubles. The artistry is arresting, but Vermiglio is hardly the sort of foreign film you would recommend to the subtitle-phobic. It expects viewers’ full attention and concentration, but in return, it transfixes and transports them to a very specific place (almost but not quite untouched by time and the outside world). Respectfully recommended for cineastes with refined tastes, Vermiglio should be a serious Oscar contender, following it theatrical opening, this Christmas Day (12/25).

©Courtesy of Janus Films & Sideshow

©Courtesy of Janus Films & Sideshow

Grade: B+

If you like the review, share your thoughts below!

Check out more of Joe’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.