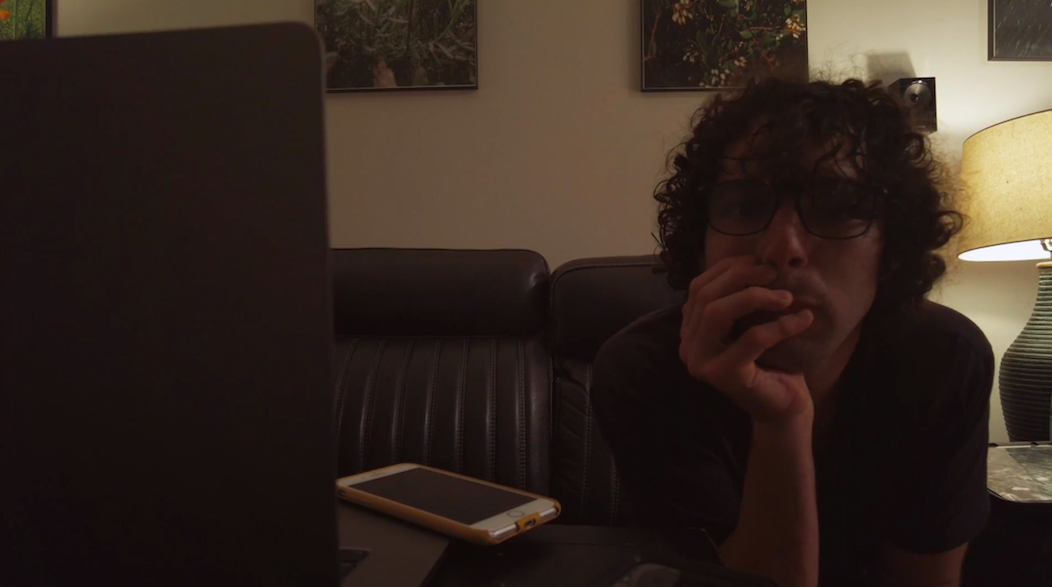

Who holds the right to decide whether a life is worth living? What factors determine the quality of a human existence? Should their be limitations to the right to die with dignity? All these questions are explored by disabled filmmaker Reid Davenport in his investigative documentary Life After.

The motion picture — which was presented at the 2025 Sundance Film Festival — begins by retracing the judicial plight of Elizabeth Bouvia, a quadriplegic victim of cerebral palsy, who in court sought the “right to die,” igniting a national debate. After years of media debate, the disabled Californian woman disappeared from public view, making Davenport wonder whether she was still alive. The film director not only discovered what happened to her, but managed to interview on camera her two sisters, Teresa and Rebecca Castner. The two provided context on their sibling’s life story, that the sensational news cycle had neglected. Elizabeth Bouvia’s main reasoning was not the wish to die, but to stop living in a body that caused her sufferance and prevented her from being autonomous.

The story of Bouvia assumes the role of battering ram for other chronicles of disabled people. Some wish to quit living voluntarily. Others criticise how certain environments facilitate euthanasia, because it’s considered more convenient by their healthcare system. The storytelling portrays these juxtapositions through examples in the United States and Canada.

In Texas, the widow of Michael Hickson recalls how her disabled husband was removed from a ventilator at an Austin hospital, against her wishes, after contracting COVID-19. Wisconsin teen Jerika Bolen, at the age of 14, decided to enter hospice and end a lifelong fight against Spinal Muscular Atrophy Type 2, that racked her body and brought continual pain. In Canada, disabled people have unprecedented access to Medical Aid in Dying (MAID), even if their deaths are not reasonably foreseeable. This is thoroughly described by Michal Kaliszan, who lives in Ontario, and was faced with the prospect of moving in a long-term care institution, and contemplated legally ending his life as “the lesser of two evils.” He eventually chose to live, once he was granted major home care support, from government programmes. His story, along with that of other interviewees, is a testimony of how the institutionalisation of people, who require special assistance, is perceived as a segregation leading to trauma.

In the film, two sides of the same coin are exposed. If one faction is fighting against the prohibitions on ending life in a medical structure, the other seems to question the facilitations in this regard. For instance, Canada’s Bill C-7 expands the law to permit anyone who considers their physical or psychological suffering to be intolerable, to qualify for death by lethal injection, even if effective medical treatments for their condition exists. As a result, more than 6700 citizens have had medically assisted deaths since it became legal in 2016. The numbers have risen exponentially through the years, adding up to 13343 in 2023, out of which 622 were terminal cases. Hence, Canada has outnumbered European nations such as The Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg who have had assisted suicide for over 20 years.

Life After tackles the moral dilemmas on this delicate issue in an all-encompassing way. The film does not forget to include a brief historical excursus about the death of the disabled people, particularly under the Nazi regime. Shocking abuses of power discriminating the disabled can also be found in the annals of the United States: compulsory sterilisation in prison system was permitted from 1907 to the 1960s, motivated by eugenics.

Reid Davenport, besides interviewing the disabled and their families, expands the conversations to individuals who have confronted the debate from different perspectives. On one hand, there are the ideas propagated by the likes of Dr. Jack Kevorkian, who publicly championed a terminal patient’s right to die by physician-assisted suicide. Along his line of thought there was also Elizabeth Bouvia’s attorney, Richard Scott, who was the co-founder of the Hemlock Society, a West Coast group with the mission “to discuss the training of counsellors prepared to help those who are considering self-deliverance.”

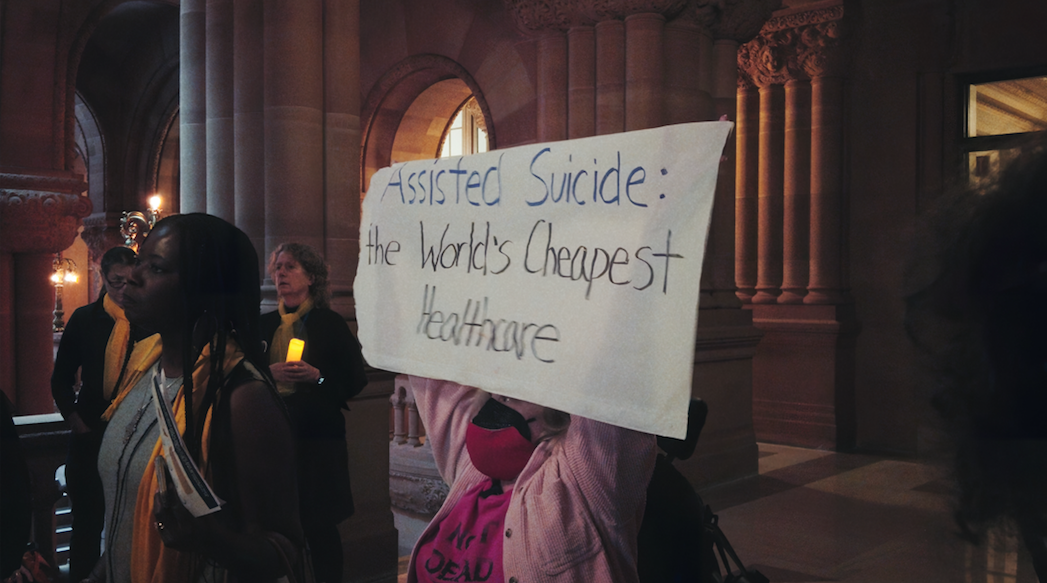

On the other hand, there are those who feel that assisted death is a governmental ploy to save money in medical management and public assistance subsidies. Alex Thompson, as the Director of Advocacy at the New York Association on Independent Living, organised the grassroots activist group Not Dead Yet against efforts to legalise assisted dying in New York. Sarah Jama, a disability justice activist, co-founded Disability Justice Network Ontario pursuing affordable housing access. She makes an emblematic reflection on the way the disabled confront the possibilities of taking charge of their lives: “Those born with disability more easily see a future. But when you acquire it, through an accident or ageing, you feel you’re losing your functionality.”

Life After amplifies the voices of the disability community fighting for justice and dignity in an unfurling matter of life and death. As Davenport remarks: “This film is not about suicide. It’s about the phenomenon that leaves people desperate to find their place in a world that perpetually rejects them.” He further emphasises how he has fallen in and out of that desperation for his entire life.

This documentary gives room for hope, for a dignified existence albeit different from that of the abled. Improving the welfare system for the impaired — allowing them to avoid assisted death as “the world’s cheapest healthcare” — is the ultimate aspiration expressed in Life After, because “maybe there’s a way to make the impossible, possible.”

Final Grade: A