©Courtesy of GKIDS

©Courtesy of GKIDS

©Courtesy of GKIDS Q : I heard that you were captivated by Uoto’s work after reading the manga ”Orb : On the Movements of the Earth,”you became intrigued by the work of manga artist Uoto. Could you share your initial impression upon reading his original work “Hyakuemu.”(In the Japanese title, the comma at the end, so rest of the titles have this comma). What aspects do you think are appropriate for an anime adaptation?

Kenji Iwaisawa: That’s right. My initial encounter with Mr. Uoto’s work was through his publication “Orb: On the Movements of the Earth”which was so captivating, I was curious about the other works created by this new young manga artist. I read “Hyakuemu.” as his debut serialized work, which has a completely different theme from “Orb : On the Movements of the Earth”, focusing on track and field. So I read it, and since it was labeled a debut work, I thought maybe it would have that fresh, debut-like quality. But actually, Uoto’s distinct authorial voice came through very strongly right from the start.

I truly felt he was a fresh voice in manga expression. I was immediately drawn to the manga artist Uoto, and after reading ‘Hyakuemu’, but I never considered adapting it to a film. A few weeks after reading ‘Hyakuemu.,’ I was offered the opportunity to direct it. The timing was perfect. So I thought, “Alright, let’s give it a shot.”

Q: I hear Uoto’s original work “Hyakuemu.” spans five volumes total. How did you extract the essence of that manga and condense it into a nearly two-hour animation film? What parts did you omit, and which did you prioritize in the adaptation? I understand you actually discussed this with Uoto himself. Could you share a bit about the process and how that production came together?

Kenji Iwaisawa: I was asked if we wanted to make an animated film when I was approached with the idea. If we wanted to make an animated film, we naturally had to make it a structured animation film.

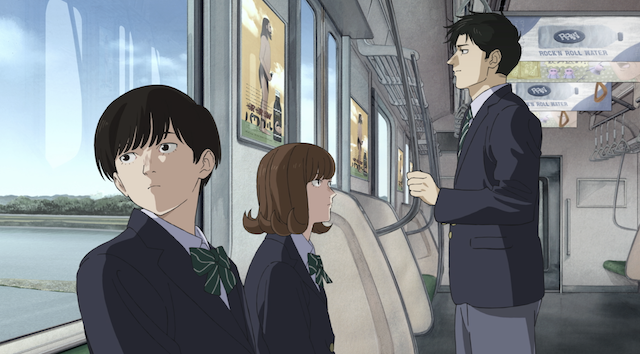

Because of the difference in expression methods between manga and film, I felt that if we were making an animated film, I would want to pursue expressions that were exclusively available in animation.

Mr. Uoto’s work is known for its use of philosophical language and monologues that reveal the inner feelings of characters. That feature was very distinct. It’s inevitable to use sound, color, and other expressive methods when translating that into visuals. In addition, with this 100-meter race ending in a matter of seconds, I had a strong desire to convey a sense of urgency, immersion, and a good rhythm.

So I said, “First, let’s try to eliminate as much of the monologue as possible in the film.” Furthermore, in terms of structure—and this appears in the film too—while the original work did depict the cruelty of track and field through the character Nigami, the volume (page count) dedicated to that aspect was a bit excessive. So, for the film, I wanted to condense it into the story of Togashi and Komiya. Consequently, I largely excluded the episodes surrounding Nigami from the original work. That made the film’s current structure feel much more cohesive.

Q: What’s fascinating is that, as you mentioned earlier, just continuing to run comes with so much drama—such as the pressure of comparison between Nigami and his father, Togashi’s contract renewal, and muscle tears, and so on. To understand the mindset and sensibilities of track athletes, have you ever actually spoken with track athletes themselves?

Kenji Iwaisawa: That’s right. Before I even started writing the script, I had the chance to speak directly with an active track and field athlete. We talked for about an hour, and I learned a lot about the real realities of track athletes’ lives. That information was very useful when creating the work, especially when writing the script. Some of those actual episodes are incorporated into the work itself.

©Courtesy of GKIDS

©Courtesy of GKIDS

Q: Did you speak with a professional athlete?

Kenji Iwaisawa: Yes, a professional athlete.

Q: Are you withholding their name? Or is it being disclosed?

Kenji Iwaisawa: The name is being disclosed. Ippei Takeda.

Q: This time, Togashi and Komiya are voiced by Tori Matsuzaka and Shota Sometani, respectively. From my perspective, Matsuzaka tends to be more outwardly expressive, leaning toward emotional performances. Sometani, on the other hand, has a cooler, more restrained quality—almost an elusive, floating quality that makes his emotions hard to grasp. Could you share the reasoning behind casting these two? What aspects of their performances were appealing?

Kenji Iwaisawa: Yeah, I definitely had that image in mind too, and I felt it synced perfectly with the role. Matsuzaka-san’s Togashi is truly the protagonist, yet it’s also a character with a lot of complexity. I thought he was someone who could express that range of acting, even through voice acting alone, so I felt he was absolutely perfect and asked him to do it.

As for Komiya, played by Mr. Sometani, there was a real overlap between my image of the character and Mr. Sometani himself. I genuinely felt it was a perfect fit for him. He really delivered that restrained feel and those delicate expressions beautifully.

Q: In music, you’ve collaborated with Hiroaki Tsutsumi, who worked on dramas like NHK’s “Omusubi” and TV anime like “Blue Spring Ride” and “Tokyo Revengers.” Did you discuss the music beforehand before starting the anime, or were you commissioned to create the music after the visuals were already completed?

Kenji Iwaisawa: Tsutsumi-san was involved from quite early in the project. Before the main “hyakum.” project, there was actually a pilot version, and we asked Tsutsumi-san to do the music for that pilot too. So he was really one of the founding members, and we spent a long time communicating our vision to him.

For example, for the main feature, I first asked him to create the main theme. Ultimately, he composed the song “100 Meters,” which is the title track used in the main feature.

At that time too, we had numerous discussions, and besides the main theme candidate used this time, we actually created three or four different songs. Each of those songs ended up being used in scenes like the relay race or Kaido’s final running sequence. So, we really went through quite a detailed back-and-forth process.

©Courtesy of GKIDS

©Courtesy of GKIDS

Q: For this project, you created a notable sequence—the high school championship final scene—using a single 3-minute-40-second take from before the match until its conclusion, employing a technique called rotoscoping. What was the reason for using this technique? What advantages did rotoscoping offer that led you to attempt this visual approach?

Kenji Iwaisawa: First, the rotoscoping technique itself is quite indispensable for me in creating animation. I’ve been using this rotoscoping method consistently since my short animation days. At this point, my animation expression is synonymous with rotoscoping. If I were told to make animation without rotoscoping, I probably couldn’t do it. It’s that essential a technique for my expression.

Of course, if it doesn’t match the work, it’s completely meaningless, so for that part—that rain scene—I actually went to watch an actual track meet after receiving the story for this project. When I went to watch the meet, I saw the entire sequence for the first time: the athletes entering, setting their starting blocks, warming up. YouTube videos only show excerpts before and after the running scenes, so I had no idea what the actual pre- and post-race moments looked like until I went to see it. When I saw it there, I realized the race had already begun from that point. It struck me that the preparation itself is part of the race. That’s when the image for that single-take shot instantly came to me right then and there.

That particular shot, where the camera swings around like that—it’s a technique that’s really hard to pull off without rotoscoping. Sure, you could probably do it with 3D if you tried, but it just wouldn’t capture that specific feel and look. So when that scene came to mind, I knew right away: this is a project that absolutely requires rotoscoping.

Q: That was truly an amazing scene. In the mixed relay, there’s a difference in how the baton is passed—the downsweep (passing the baton horizontally) and the press pass (passing the baton vertically, pushing it forward to the next runner). The Japanese team is world-renowned for their baton-passing technique, right? Did that relay scene also have a distinctive feature? Were there any specific aspects you focused on?

Kenji Iwaisawa: That was kept true to the original work. The Japanese national team uses an underhand pass, and I think they aimed for fidelity to the source material. Story-wise, it’s probably something like the Baton Pass that you can’t do without proper practice. Including that dramatic build-up, I believe it was present in the original work.

©Courtesy of GKIDS

©Courtesy of GKIDS

Q: Among the characters competing in this 100-meter dash, there are those like Kaido who don’t care about records, those who meticulously calculate and prepare thoroughly, and those who compete somewhat emotionally. When adapting the original work into an anime, were there any aspects you focused on regarding the characters? Were there any points you felt should be incorporated into the characters?

Kenji Iwaisawa: For the characters, I tried my best not to change the core aspects from the original work. Where character traits inevitably shifted due to story structure—especially Togashi’s character—some episodes that couldn’t be depicted in the original due to cuts ended up being included. So there are parts that inevitably changed in those areas. But I consciously aimed to adapt it in a way that preserved the original impression as much as possible.

Q: This film will be distributed in the U.S. through GKIDS. What aspects of the film would you like American audiences to see?

Kenji Iwaisawa: Well, this isn’t necessarily unique to America, but to begin with, visual works centered on the 100-meter dash are quite rare. Even in Japan, I doubt there are any animated works like this. There are works about long-distance running or ekiden( a Lonh-distance running multi-stage relay race, mostly held on roads) relay races, but nothing that focuses so directly and straightforwardly on a short-distance event. That rarity means it’s likely perceived as a unique work in pretty much any country.

I did think quite a bit about whether the soundtrack’s music would resonate universally during climactic moments. In terms of direction, I wondered if the way we used the music might actually appeal to American audiences too. So yes, that was something I was conscious of.

Q: I understand that you have a project based on Hideaki Arai’s original work “Hina” (English title: ‘Hina is Beautiful’) is underway. It aims to develop and pitch the project, secure funding, and produce a feature-length animated film based on a roughly 3-minute pilot film. I also heard this pilot was screened at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival’s Annecy Animation Showcase. Will this become your next project?

Kenji Iwaisawa: That’s right. “Hina is Beautiful” was originally a pilot version, a pilot for a feature-length film. So next, we’re preparing the next work based on “Hina is Beautiful“.

©Courtesy of GKIDS

If you like the interview, share your thoughts below!

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.