©Courtesy of GKIDS

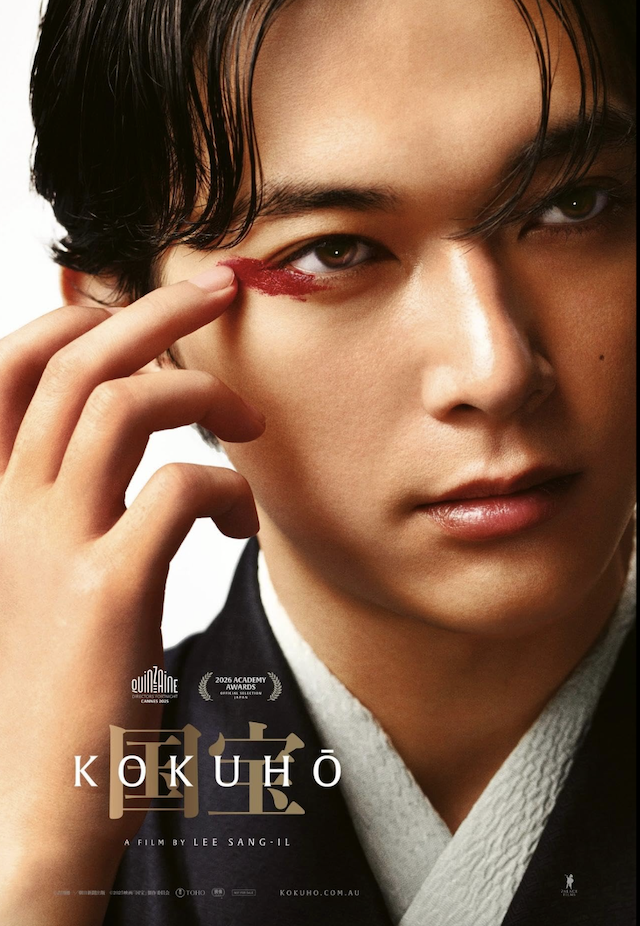

Q&A with Actor Ryo Yoshizawa and Director Lee-Sang-il (The Q&A took place at the Japan Society, moderated by Alison Willmore)

Q :Lee-san,your interest in Kabuki is something that has stretched back years. It actually predates the novel on which this film was based. Can you start by telling us a little bit about what felt so compelling to you about kabuki as a subject for a film, and then how what ultimately became a story made its way to the screen?

Lee Sang-il: That’s right. It was about 15 years ago. A certain Kabuki actor (Utaemon Nakamura—who dedicated his entire life to Kabuki and was called the pinnacle of onnagata in the postwar Kabuki world. He never engaged in theatrical activities outside of Kabuki and dance, nor did he appear in films or TV dramas. However, this film is based on the novel of the same name. Its author, Shuichi Yoshida, collaborated with Kabuki actor Nakamura Ganjiro (66) and spent three years learning behind the scenes as a stagehand at a Kabuki theater before writing this novel.) I became very interested in him.

He was active from before the war, and including the postwar period, he really elevated Kabuki, especially dramatically raising the value of the onnagata role. He was born with a disability in one leg and underwent major surgery as a child. Despite this handicap, he continued performing on stage. Unfortunately, by the time I became interested in him, he had already passed away. I was able to see some of the remaining literature and, though from his later years, some footage of his performances.

Among those recordings was footage of “Kyōkako Musume Dōjōji,” just as Yoshida-kun had written in the original script. He was so beautiful and elegant, you scarcely felt his disability at all. He seemed to be in a state of selflessness, or perhaps he had entered some realm only he could reach. Yet simultaneously, I sensed something slightly manic, or perhaps grotesque. There were also some TV interview clips left, where he appeared not as a kabuki actor but in his everyday self.

He looked like a very neat, petite old man wearing glasses, Yet, in his mannerisms and speech, there was something feminine, or rather, a girlish aura about him. It felt as if his very humanity, his life, had been deeply infiltrated and completely overtaken by something from the Kabuki stage, from being an onnagata, from being an actor. I felt I was catching a glimpse of the intense, dramatic life of a man who had devoted himself entirely to Kabuki. That was probably the first seed that made me want to make a film about him. I’ve talked too much for a start, so (looking at Mr. Yoshizawa) please focus on listening to his story from here on.

Q : Yoshizawa-san, I know that Lee-san has said that he knew from the start that he wanted to to find film actors as opposed to Kabuki actors for these roles, but that meant that you had to do some incredibly intensive studying and training in the world of Kabuki. What was your relationship with Kabuki before this project and what was it like to undergo over a year and half of training. Is that right?

Ryo Yoshizawa: Well, I received this offer specifically for kabuki, and while I’d seen it a few times before, I really knew nothing about the inner workings of being a kabuki actor. I started completely from scratch. Well, I started Kabuki training about a year and a half before filming began. Since I trained for a year and a half, I initially thought I might be able to do it to some extent. But the more I did it, the more I felt the sheer power of actual Kabuki actors every day.

They’ve been building their craft as actors since birth, performing on stage with decades of accumulated skill. The more I trained, the more I realized it was impossible to catch up in just a year and a half. We practiced the most minute details—just Suri-ashi(Suri-ashi is a fundamental footwork technique), just walking—accumulating these tiny elements. Even knowing I couldn’t reach their level, I approached this work with a kind of resolve, a stubbornness, that I had to keep pushing forward. And in the end, I believe that was the most essential emotion needed to play the role of Kikuo.

©Courtesy of GKIDS

©Courtesy of GKIDS

(Q) : This film is very much about the actors performing kabuki as opposed to the experience of watching it. But there are some incredible sequences in which we see the Kabuki performances. Lee-san, I was wondering if you could speak to how you wanted to shoot those performances in terms of what perspective you wanted to show. And I was wondering if you speak a little bit you, you worked with cinematographer Sofian El Fani, who shot “Blue is the Warmest Colour.” Is it true that you wanted specifically someone who is not that familiar with Kabuki

Lee Sang-il: First, since Sofian had said she’d never seen kabuki before, I was very interested in how she might perceive its aesthetic aspects from this new perspective, this new side of her. But what I was conscious of was creating a sense through the visuals that would blur the boundary between the audience watching kabuki and the people on stage. So, I particularly focused on the perspective of the actor’s view of the (Kabuki) world. And of course, the actor on stage—for example, Ohatsu—plays the role of Ohatsu.

But within Yoshizawa-kun, I wanted him to swallow both that role and the protagonist himself, Kikuo. Not just play the role of Ohatsu, but capture the weight Kikuo carries, the conflicts Kikuo faces, including his ecstasy on stage. I conveyed to Sofian my desire to somehow zoom in and capture the swirling essence of Kikuo the human actor himself, how he stands on that stage.

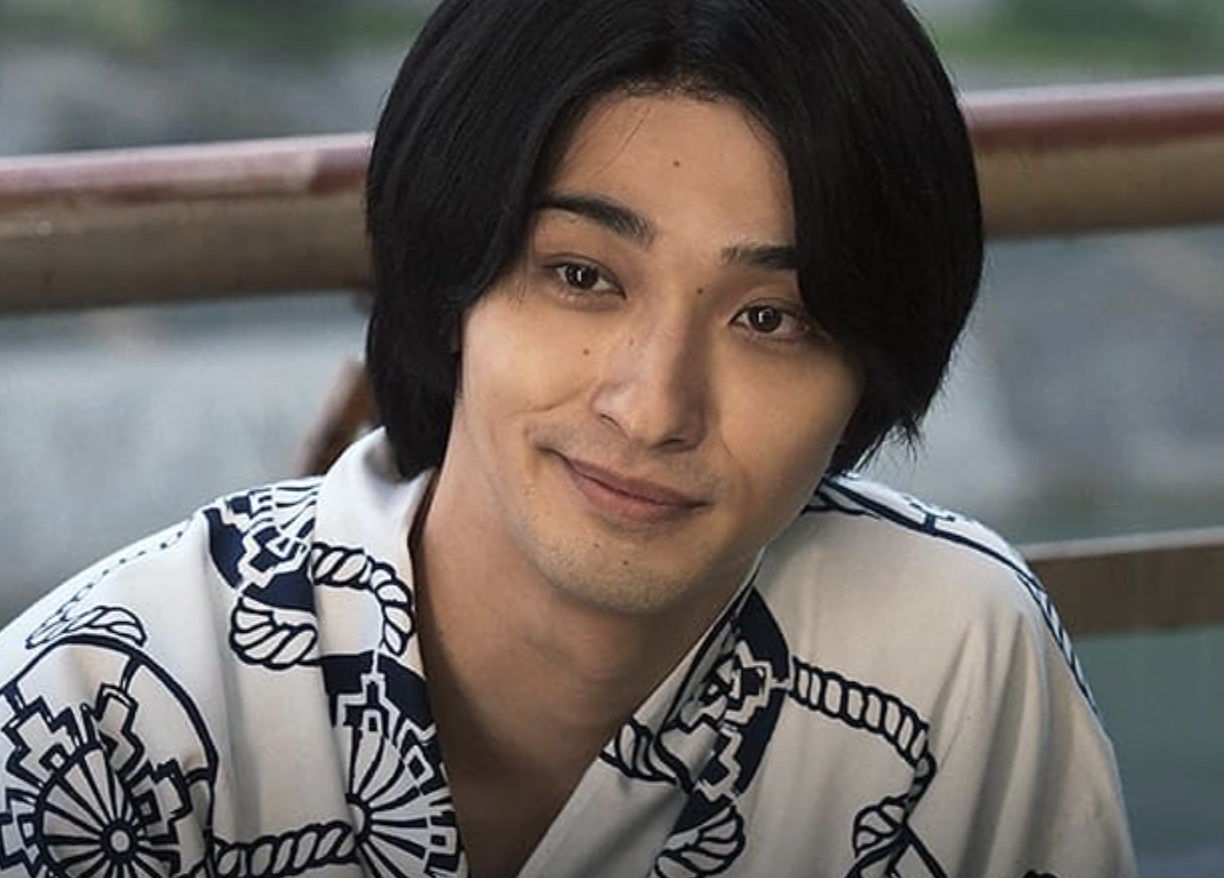

Q : Yoshiszawa-san, this film spans 50 years and you are playing Kikuo for aside from that early section for all of them. What was it like to play a character over these different life stages and to take him from being a young man to an older one?

Ryo Yoshizawa : Of course, as the character ages, I had to portray that aging process through special makeup and such. But as the director mentioned earlier, having lived as an onnagata for so long, especially with a character like Kikuo, I envisioned him becoming increasingly absorbed into the world of kabuki. It felt like the happiness of his daily life was being gradually sucked into the stage. As the director mentioned earlier, the older he gets, the more the onnagata role permeates his daily life. I was conscious of how that onnagata way of living would naturally seep into his posture, his way of speaking, the movement of his gaze—these everyday aspects.

Q : I wanted to ask about the character Shunsuke(Played by Ryusei Yokohama), who is the other most important character in the film. And you know, this is a story of someone who has many people passed through his life. But like throughout the film is this incredibly complicated friendship and rivalry. Can you tell me a little bit about casting that role and how you built that dynamic between your two actors?

Lee Sang-il: Well, whether it’s sports or art, stories about rivals competing against each other are really quite common. But what characterizes this particular story is that, for example, in films like Amadeus or the relationship between Mozart and (Antonio) Salieri, the jealousy and envy within that dynamic, or these dark feelings swirling internally, are often depicted. Well, those elements aren’t entirely absent here, but for them, what’s more central is something like kabuki, or the pursuit of mastering their art.

They are completely aligned in that. They are heading towards the same world, you know… not exactly two becoming one, but they are connected by something like a beautiful spirituality, striving for an art that transcends jealousy or resentment. I see the characters Shunsuke and Kikuo as very contrasting. Even in their costumes, the color schemes and styling are deliberately set up as opposites. Kikuo is like a very cold flame—burning intensely, yet possessing an icy core. Shunsuke, on the other hand, is a true red flame, the kind that would burn you if you touched it. They’re opposites, yet I saw them as sharing an equally intense passion.

©Courtesy of GKIDS

©Courtesy of GKIDS

Q : Yoshizawa-san, throughout the film, we see how physically and emotionally intense the performances art of Kabuki is. I was wondering if there was a particulars, not to mention the costume, the costume changes and the kind of makeup. I was wondering if there is a particular sequence that stood out in your mind as either maybe the one that was most challenging or the one that you feel the proudest of.

Ryo Yoshizawa: There wasn’t a single scene that wasn’t difficult, so it was tough overall. But honestly, the hardest parts were the dancing on stage and portraying Ohatsu as Kikuo. We spent a year and a half rehearsing, striving to perfect how beautifully I could dance as Kikuo. But then, during the actual performance, the director came up to me and said, “I know you can dance beautifully, but dance as Kikuo.” That was his direction. At first, I had no idea what he meant. But then I realized… it wasn’t about being there as a kabuki actor, though that part was true too.

He was asking me to act as Kikuo carrying the weight of the role of Ohatsu, incorporating everything about his life up to that point and the situation he was in right then. So compared to an actual kabuki actor, there were many parts where I became very emotional. and there were parts where we deliberately played with emotion instead of relying on stylized beauty. I suppose that’s where it differs from traditional kabuki. But when I saw it in the film, it felt incredibly dramatic. Watching it, I understood what the director meant, and at the same time, I grasped why we film actors were chosen for this work, rather than kabuki actors.

Lee Sang-il : Did you realize it after it was over? (wry smile)

Q : And Lee-san, this film, which is also Japan’s submission for the Oscars, has been enormously successful. It has really been a phenomenon. Did it surprise you that people connected so much with this traditional arts? And has it driven any interest in Kabuki?

Lee Sang-il: I hear kabuki tickets are quite hard to come by these days. Many people come to Japanese theaters too, and some of them have seen it multiple times. I never imagined a three-hour film about kabuki would spread like this, but I suppose it really comes down to the theater environment, the screen itself. The visuals and sound are important, but what’s truly vital is the immersive experience that makes you forget time, and the theater itself. This beauty, and then the actors performing kabuki—or rather, the artists, the way people who pursue art to its ultimate limit live their lives—is something more than just following the story. I feel like audiences are going to the theater multiple times to soak in their way of life, and then wanting to reconfirm that experience they’ve absorbed.

©Courtesy of GKIDS

©Courtesy of GKIDS

If you like the Q&A, share your thoughts below!

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.