American director James Ivory (born 1928) has become known for his unrivaled screen adaptations of major classic and contemporary novels, including A Room With a View, Howards End, and The Remains of the Day. He has also enjoyed a successful and lucrative partnership with Indian producer Ismail Merchant, in their independent film company, Merchant Ivory Productions

Q&A with Director James Ivory and Michael Barker(Michael Barker is the Co-President and Co-Founder of Sony Pictures Classics)

Q: How do you feel about this book, ‘Solid Ivory”?

JI: Well, I’m surprised that people want to read it and buy it. I mean I never imagined that. I had no plan to ever especially write a book of memoir. I’d written the pieces over the years just for my own pleasure, mostly. Something would happen and I would write about it. I never thought it would be published, unless sometimes I was assigned to do something.

There’s a long piece in there on Vanessa Redgrave that was assigned by the British film magazine Sight & Sound. But on the whole, I just did them for fun, really, and then put them away.

Then Peter Cameron, who was the author of the novel The City of Your Final Destination, which was the last feature that I made. He saw some of the things that I wrote and he showed them to John Farrar at Farrar, Straus and Giroux, and said “Well, I think there’s a book here.” So we gathered it all together – some of it, anyway – and it became this book. And I’m surprised that people seem to be quite worked up over it.

Q: People want to know what is going on behind the scenes not only with the movies, but also the subtext of you. We see a lot about your childhood in the book that we don’t know anything about. Tell everyone how you met Ismael?(Ismael Merchant, they established a company called, Merchant Ivory Productions)

JI: There was a screening of my second documentary film, which is a film called “The Sword and the Flute”, which is about Indian miniature painting, that was being screened at the Indian consulate in New York. Mutual friends said to Ismael, “You should go and see that film because it’s really nice”. One of them was Saeed Jaffrey, the actor who had spoken the narration.

So Ismael came to see it, and then after the screening I came out of the building and he came up to me. He was standing out on East 64th Street right in front of the building, and he came up and said how much he liked the movie. We started talking, and sooner or later he said “Well, let’s go for coffee”, which we did. We went around the corner and up Madison Avenue and then had coffee.

Q: And at what point did Ruth come in? (Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, a screenwriter for “A Room with a View,” “Howards End,” and “The Remains of the Day”)

JI: Well, several months later, I was at that point working on another Indian documentary, which was a portrait of the city of Delhi (“The Delhi Way”) and I wanted to go back. I had shot a lot of it, most of it, but I wanted to go back to India, to Delhi, and shoot some more. So I went to India.

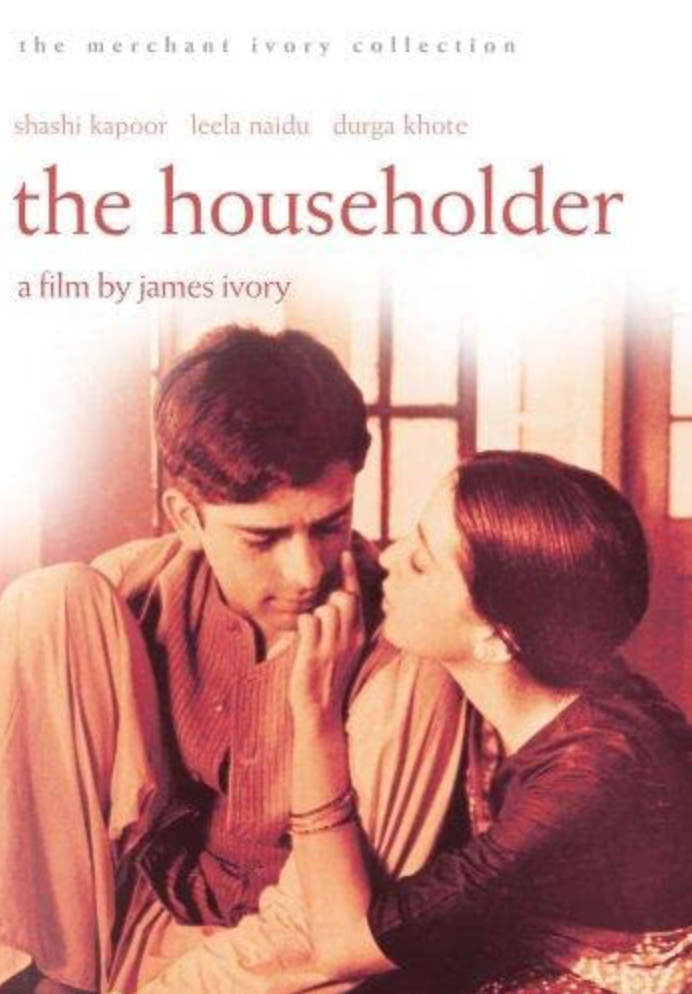

Ismael was also in India at that time, and he was going to produce a feature film for some Americans, but that sort of fell through. But he had read Ruth’s novel The Householder, and someone out in Hollywood, where he had gone and spent some time, said “Oh, you should make that into a movie because the studios will never do a deal.”

It was Ruth’s fourth novel; he wouldn’t have read very much of Ruth’s books. So he said “We’re going to make “The Householder” and you’re going to direct it. But we need a script writer.” And I said “Well, let’s get Ruth if she wants to do it.”

So we went to see her in Delhi. He got her telephone number somehow and he called, and she didn’t want to talk to anybody. She said that Mrs. Jhabvala wasn’t there – she pretended to be her own mother-in-law. Ismael wasn’t fooled. Finally, we got in, and we met and there was this meeting.

We said what we wanted to do, and Ismael made this pitch to her that she should write the script. She said “I’ve never written a screenplay.” And then the famous retort that he’s told every journalist in the world for years: “Well, I’ve never produced a film and Jim’s never directed one.” So she agreed. And we made “The Householder”.

The interesting thing about “The Householder” was that it was, in fact, sold to a Hollywood studio, Columbia Pictures, who distributed it. Ismael sold it to – I’m not sure who it was at Columbia that he knew, but he knew people at Columbia. Right away he started pitching that film and lo and behold, he succeeded. We made this film in India and then we brought it here to New York.

Q: At that time, did you know you were going to be a team going forward?

JI: Yeah. We made “The Householder” and we wanted to make something else, some other films as well. We became a team and the desire was to make certain films that he would produce and I would direct.

Q: And how many films did the three of you do together?

JI: Oh, gosh – twenty-seven, I think. Yeah, twenty-seven features, but then also three films made for television.

Q: But what’s interesting is, the trademark was for you to be so independent, and that’s the only way you could have done that. You couldn’t have done something like that dealing with Hollywood studios, could you?

JI: No, but in time we did deal with Hollywood studios, and we didn’t get in trouble with them. We really didn’t. By the time that we began to make films for the studios — first it was Fox and then Sony at one point, and Columbia Pictures – by that time, people in the studios kindof let us alone because they knew that what we did was probably okay and had a reasonable possibility of being commercially okay, and we were successful. So they left us alone and they never leaned on us. That never happened even once.

Q: What I remember about “The Remains of the Day” is we were moving over from Orion to Sony — which is a whole other story, Sony Classics – and “Howard’s End” was with us at Orion Classics, through Sleight-of-Hand. Ismael moved the movie over to us at Sony Classics. But what I remember is you had told me and Tom Bernard how much you loved that book The Remains of the Day. We had a meeting with Peter Guber and he said “Oh, Mike Nichols doesn’t want to direct it because the script is so horrible from Harold Pinter.”

JI: It wasn’t so horrible, a lot of it’s in Ruth’s script. She liked it

Q: Yeah. But that’s the way they talked about it, and they thought it was so unstudio-like. So we showed them “Howard’s End” and we told them that you loved that you loved that Ishiguro book, and the rest was – I mean, what a great movie.

JI: Another thing that happened was just before that, “Howard’s End” became a big box office success. I don’t think Columbia would have come to us offering us that if it hadn’t been. Ismael was very clever about it. He would never show “Howard’s End” to any studio executive in their home. If they wanted to see the film and it had fantastic reviews and was doing fantastic business, he would arrange for a screening, or they would have to go to the theater. Actually buy a ticket and go to the theater. And he stuck to that, and it helped somehow.

Q: What a lot of people don’t know is, that is Sony Classics’ first film. We were always interested in that screenplay of “Howard’s End” even when it belonged to someone else – Samuel Goldwyn for several years. Then Ismael got it away from them and then came to us at Orion Classics. And then when we moved to Sony, we figured out a way to get it from Orion and into Sony. The film was like lightning in a bottle. When people saw it, they just adored it.

JI: It has such extraordinary performances.

Q: I remember when you and Ismael brought it to Cannes and you and Ismael had a big villa, and all the actors stayed together, with Shashi Kapoor as the chef with his smile, and what was a big way to present a film in an especially unique way that was different from anybody else.

JI: He would always rent a villa and then fill it up with all the people who worked on the films. And I mean fill it up.

Q: Yeah. Well, maybe we ought to look at a scene from “Howard’s End”.

[Showing Clip]

Q: That was the first role that Anthony Hopkins played after Hannibal Lechter. But another remarkable thing was your cinematographer, because we with you made 70mm prints for the Paris Theater and a few other theaters, and it was just glorious in 70 millimeter. Can you talk about working with your DPs, and specifically that one?

JI: The cinematographer was Tony Pierce-Roberts, and I wanted to do something more. The “more” was to make the 70mm prints with all the rigamarole that that entails. I felt it’s such a story it needed something more.

Q: It was really remarkable. David Schwartz is here, who runs the Paris Theater now, and I can tell you that the Paris Theater showed no more glorious film than that film in 70 millimeter. You played many of your films at the Paris Theater.

JI: We did, from “The Europeans” down to – I think even “The City of Your Final Destination: played there. Pretty much all of them, and once in awhile I would do something and the distributor didn’t want it to play at the Paris. But on the whole, they did.

Q: “Howard’s End” played almost a year there. But you’ve worked with several cinematographers. Do you have favorites?

JI: Well, when I’m working with them, they are my favorite. I trust them, and we always have a good relationship. I’ve never had a bad relationship with my cinematographer. But it’s also that sometimes, someone that you want to work with is making another film so they’re not available. Then you have to get a different cinematographer.

Or you might be working in a country where you want to take on a local cinematographer. When we began to make films in Paris, we started making films with a wonderful, wonderful cinematographer named Pierre Lhomme, and we made most of our French films with him. If we were in India, then we would work with Ray’s photographer, Subrata Mitra, and I made four films with him.

Q: Jim and Ismael have done a lot for the restoration of films and film history. We were part of this, and the Academy was part of this in restoring so many of Satyajit Ray’s masterpieces in the ‘90s. I remember when we banded with you and Ismael to get him a special Oscar. That was so great. The actors that you work with are so phenomenal. It must be arduous work to get some of these actors, too.

JI: Well, with Emma Thompson, several actresses read for the part, all on the same day, and Emma was the last one to read. She didn’t have her script, or she had lost it or something, so she read straight from the novel. It was at the end of the day, I don’t remember what scene, and I just cast her immediately on the basis of that.

If you are after somebody in particular, usually you don’t have to convince them too much. If a part was a good one, and they were free, they tended to come along and work in our movies.

Sometimes there was a difficulty with Vanessa Redgrave because we wanted Vanessa Redgrave very much to do “The Bostonians” but she had all sorts of other projects. Then when she began to have her political troubles and suddenly wasn’t cast anymore in anything and nobody wanted to work with her, and she was able to then be in “The Bostonians”.

Suddenly she was saying “I couldn’t really play a woman like Olive Chancellor/ I couldn’t play that part. I don’t see myself in that kind of a role.” And you just had to accept that.

Q: It’s one of her greatest performances.

JI: It is. And then when she decided to do it, she was adamant that she would do it.

Q: One of the things that’s so remarkable about “Howard’s End” is she’s in the first eight minutes and her presence is felt throughout the entire movie. The story provides that. It’s Oscar-worthy for like two and a half scenes. That is remarkable what you do with her. So many of these actors you work with again and again, so it’s like a family or some kind of company you have that travels with you.

JI: Well, yeah, if you get a great performance out of somebody and then a part comes along that you think that actor could do well, of course you want them. You developed a way of working, a friendship, and you go after them.

Q: Your supporting players, too, like Tim Pigott-Smith. You used him over and over again.

JI: Yes.

Q: Maybe it’s the John Ford model.

JI: But you want to put them in different kinds of roles, also. He’s talking there about his son, who was played by James Wilby in the film, and who also played Maurice in “Maurice”. While we were making “Maurice”, he had a scene which was cut from the film. He had a scene with his sisters and he was horrible to them. He spoke to them in a terrible way. It was appropriate for the scene. And while we were making it, I thought he would make a fantastic villain. So the next film with him, one or two later, was this film. I cast him as the villainous son, and he was incredible.

Q: He was great.

JI: Yeah. He played, really, sort of a fool, a villainous fool, and he was extraordinary.

Q: It might be a good time to play “Maurice” now. James Wilby is in “Maurice” with Hugh Grant and Rupert Graves, and that was such an important movie in so many ways. It was between “A Room with a View” and “Howard’s End”.

There was something about it that seemed very honest and raw in a new sort of way for you. It’s an incredible movie.

[Showing Clip]

Q: Ruth did not write that screenplay. You wrote it.

JI: I had a partner, because I didn’t feel that I would maybe get it all right, the whole English social scene, that world that the book shows. So I had a good [deal] with Kit Hesketh-Harvey, and we wrote it together. Both of us wrote it. Thank goodness he did, because he was spot-on in so many ways.

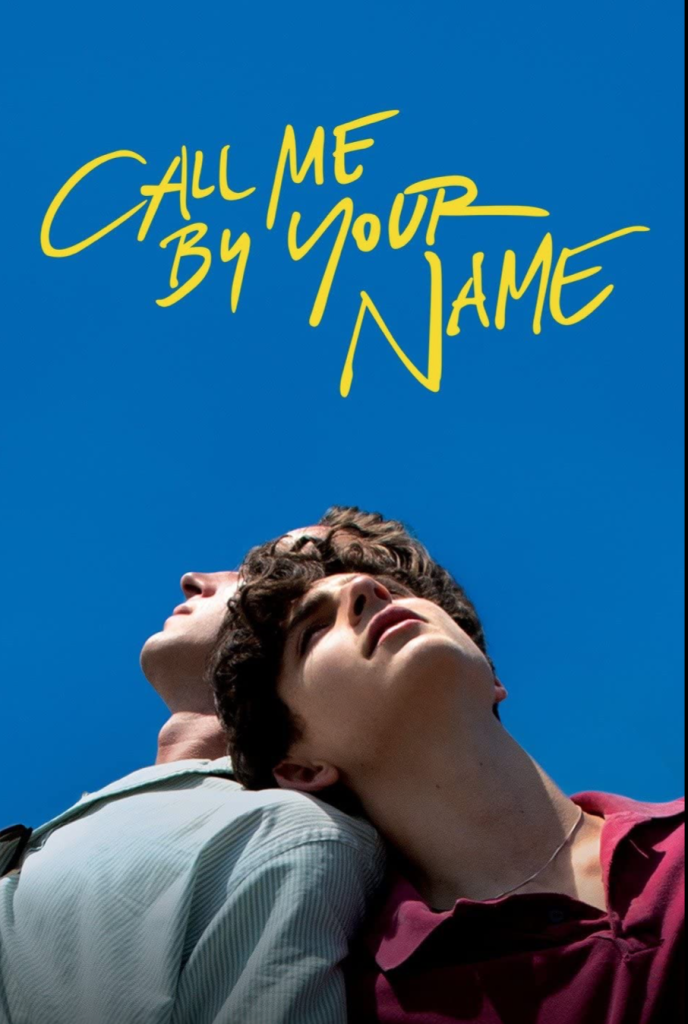

Q: So you wrote that screenplay with him, and you wrote “Call Me By Your Name”. Were there other screenplays you wrote?

JI: I worked on certain other screenplays with Ruth. Sometimes we worked together on a screenplay – like “The Divorce”, for instance. The way we would work – if she was adapting a book and I wasn’t going to do it with her, then she would work on it for months and months. Sometimes she was in New York and sometimes she was in India, and I wouldn’t see it for a long time.

But if we were working together and both doing an adaptation as a team, then I would do mine first. Then she would take my version and she would work from it, but not go back to the book. She might go back to the book to get little bits and pieces she thought were useful. But she would then work from my screenplay rather than the original novel. That’s how we worked. That seemed to work out all right.

Q: The screenplay for “Call Me By Your Name” – was that difficult to write? The book is so —

JI: Not terribly. I didn’t work all the time on it. I’d go in and work on it a bit and I’d do something else, and then I’d come back and do some more. I think it took about three months of – not constant, every-day work, but about three months.

Q: Is the final film very close to the screenplay you wrote?

JI: It is. I saw the film the other night. They were showing it in Charleston – I just had come from Charleston – and I hadn’t seen it in awhile. It’s very like, sometimes I’m surprised. They kept in a lot of stuff that I wrote. Yeah, it was pretty much as I wrote it.

Q: Probably now’s the time to show the scene from that film, which does show off the screenplay.

[Showing Clip]

Q: Can you speak about the controversy about whether or not there was enough nudity in this film, or not enough nudity?

JI: Well, here’s what happened. American actors, male actors, don’t like to do nudity. They don‘t like nude scenes and they don’t do them, on the whole. Except for Viggo Mortensen. He likes them.

So it was in the contract for the two boys with their American agents that they would not have to do nude scenes. But there wasn’t any necessity of really doing nude scenes. The way I wrote the script – they were in bed together, and so on – but it wasn’t necessary to have frontal nudity. It just wasn’t.

The way I wrote it, they would have learned everything you wanted to know about their lovemaking that they needed to know. So that’s the way it was. And both Luca and me, we had a lot of nude men in our movies. I mean, look at what you see in “A Room With a View”, where one of the boys goes swimming.

But people took that up and said there wasn’t enough, and so forth. But there could be, we wanted them to. There might have been a glimpse here and there, that sort of thing, they’re getting in or out of their bathing suits or whatever. But the agents said they didn’t have to do it, so they didn’t want to.

Q: In writing the book, or in assembling the book, did you write new things to fill in gaps that you felt were missing? And when you read your old material, were there things that you decided to revise?

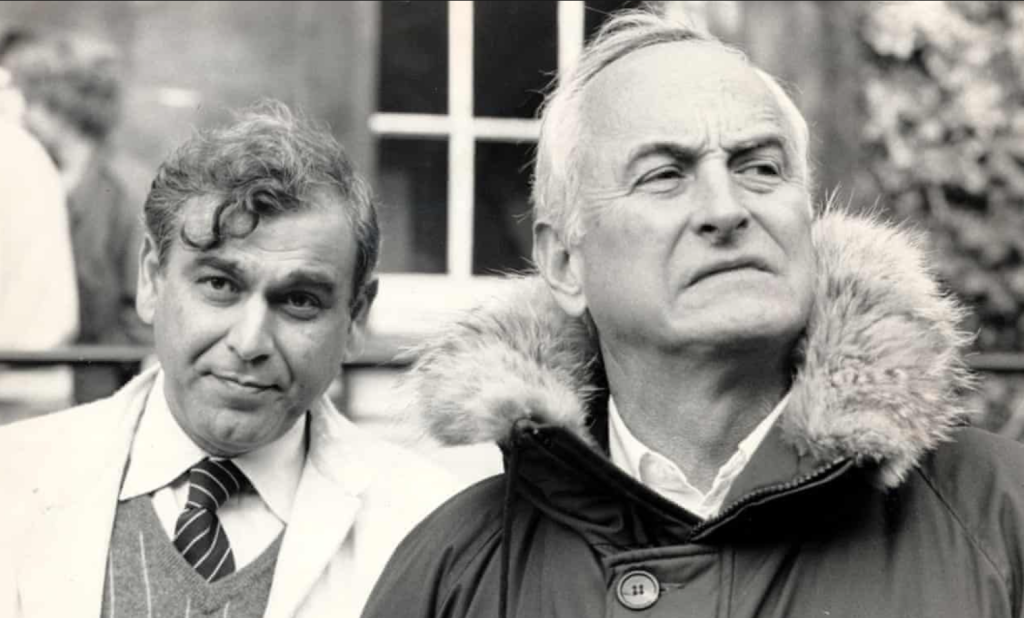

JI: Well, here and there, once in awhile I would add something or I would take something out. I had to give things a shape sometimes. But what the publisher wanted was three things, basically, that I had not written. One was a number of portraits in the book, all different kinds of people that I’d met – some very famous people, some not famous at all – as people I knew, and I wanted to write about. So they said “Do a portrait of Ismael”, although Ismael appears a lot in the book and there are many scenes with Ismael, but they said do a portrait of Ismael. “Do one of Ruth”. And then “Write something about “Call Me By Your Name”. So those were the three things I had to do.

After I got done with Ismael and Ruth, and it was no longer possible to add things, they wanted to go to press and bring it out. And they said they would, and all that. But I had the feeling that I hadn’t really done Ismael justice. There were so many more things I could have put in there, and I wish I had. Maybe someday, if there is ever a second edition or something, I’ll be able to do that.

I thought the same thing about Ruth. But it’s very, very hard, I feel, to write about your closest friends. You know so much but at the same time, a lot of what you know is a felt thing, and it doesn’t lend itself to description or descriptive writing, I feel. Unless you’re such a clever writer that you can bring life to those feelings. One tries to, of course, but in general I feel I haven’t done Ismael justice.

Q: Well, I think the number of years we’ve known you – decades – the love that you and Ismael had for each other, we never got a window into that. We just felt it.

JI: An interesting thing about Ismael – I’ve been thinking about it – if you compare the films that he directed with my films, his films would be four features and two shorts. His films are about poor people, people who are miserable and have terrible lives, and are on the edge of despair. Except for the film that he made with Jeanne Moreau, called “The Proprietor”, that is a different kind of film.

Somehow between his films and mine, which are pretty much about contented upper middle class, well-off people, there’s a balance. It was like he was bringing a kind of balance into Merchant-Ivory that it lacked. You have to see his films.

There’s a really wonderful one about an old poet who was drunk all the time, an Urdu poet. Ismael was absolutely fluent in Urdu, wrote it and read it, and he wanted to make a film about this classical Urdu poet. It wasn’t a real living poet, it was a novel. He was drunk and falling down, but it was so powerful. Shashi Kapoor played that part. Shashi Kapoor, who was our young leading man from our very first film, who was beyond handsome, he was so sublime looking and here he was at the end of his career as this fat, drunken old Urdu poet. He had a ball doing it. He loved playing that part. But by this time, he was grossly fat.

Q: It’s all a matter of taste. Ismael’s taste, your taste, and Ruth’s taste. All three of you were very different. Somehow you got together.

JI: Well, Ruth didn’t always like the things I wanted to do. I never did something that she really didn’t want me to make. Possibly “Maurice” – she thought that “Maurice” was not really a good model of E. M. Forster, and that was generally said by people who knew his work and critics and so forth. “Maurice” of all the novels was least good. She always said about that that the film was “sub-Ivory” and the novel was “sub-Forster”. She never changed her opinion on that.

Q: I so disagree with her on that. I think one of the reasons those critics in the early years said that was a sub-par novel is they didn’t like what to them was “transgressive”.

JI: No, it was a little more than that. One of the things that happened in the novel and which we kindof got away from with the help of Ruth in the film, was that Clive leaves Maurice in England and goes off to Greece on a holiday. When Clive goes off to Greece, he decides while he’s there that homosexuality is not for him, and he’s not homosexual, doesn’t want to be, and he’s over and done with it.

Well, that never happens, almost. He comes back and announces that to Maurice. That was not accepted. Nobody who ever read that book ever thought that was valid or it could be like that. It was just a novelist’s easy way of not being put in prison. That story, which has a happy ending, could not really have been published in England before 1961.

Q: I wanted to ask you about your project you’re working on now about Richard II, and how long you’ve wanted to work on that?

JI: Well, if Ismael had been around when we wanted to do it and I really got going on Richard II, and we had a great screenplay written by Chris Herriott. If Ismael had been around, I’m sure that film would have been made five years, ten years ago, whatever. But he died before we could really do it, and we were able to get the financing for it. So it just never happened.

Q: Did you have an actor in mind for Richard the Second?

JI: Several, actually.

Q: I was wondering if you could speak on the Merchant-Ivory editorial process and what it would be like after filming it, getting in the room with Ismael and editing it?

JI: Well, Ismael was never very interested in being in the editing room. He’d wander in sometimes. That film, like most of the films from that time on were edited in upstate New York at my house there, and if he was around, he would come in. He wasn’t someone who sat in the editing room and said do this or do that. The person who was interested in being in the editing room at a certain point was Ruth.

I don’t know how many other directors are here, or how many editors are here, but all first cuts are monstrous awful things, shapeless and terrible. “A Room With a View” was like that.

So Ruth would come in and she’d be very very helpful in helping me and the editor to shape the cut film. She’d help us get rid of stuff that was not good enough. Occasionally we would shoot something else, once in a great while. But she was very very helpful in bringing us to the final form and cut of the film.

And the only other person who did that with me was Satyajit Ray, who recut “The Householder” from start to finish, and turned the film into a big flashback. He was the only person that ever did that.

Q: Do you think it was an improvement on the film?

JI: Oh, enormously! Oh yes, of course it was. Are you kidding?

Q: Many directors wouldn’t admit that.

JI: We loaded that film, all these cans of film and cans of sound, on a train and went right across India from Bombay to Calcutta to bring it to him. He said “I’ll do it. I like the film. I’ll help you with the editing, but I don’t want you to interfere while I’m doing that. Let me do what I want to do, and then if you don’t like it, you can change it, put it back the way it was.”

So I was always in the editing room while he was working, but pretty much stayed out of his way. I think I put one scene back. I was just happy that he was doing it.

Q: Another movie that we released was “The White Countess”. That was another Ishiguro screenplay. It had Ralph Fiennes. It was a bringing together of the Redgrave family, Vanessa and Lynne came together for the first time in awhile. And Natasha Richardson is magnificent in that film. That is one of your great movies that people don’t really talk about.

JI: I liked that film a lot. It has a central flaw and it’s my fault.

Q: And what was that?

JI: When Ralph Fiennes said he wanted to play the lead in that, he kept saying, “you know, I wish that character had something else – a disease, some other thing. And I came up with the idea that we would make him blind. When he heard that, he said “That’s great. I love it. Let’s do it.”

So Ralph Fiennes is playing a blind man. Well, that’s all fine, until the end of the film when you have the bombardment of Shanghai by the Japanese and all the people fleeing to the docks. And then you have Ralph Fiennes, impeccably dressed with the perfect hat, going along with his cane, through all the mayhem and the bomb blasts and not falling into the water and so forth, as if he knew the way. It just strikes you as phony.

Q: I wish you hadn’t told me that.

JI: I am sorry, but that’s what I feel about it. Nobody could possibly have gotten around those Shanghai docks which were being bombed by the Japanese and survived and gotten on a boat and gone off to Macau as the people do.

It would not be possible. You don’t believe it – or I don’t believe it. That’s my fault. I should never, ever have thought of such a stupid idea.

Q: What was the most challenging element of adapting “Call Me By Your Name”, and why didn’t you actually direct it?

JI: I don’t know. I didn’t feel that there was any particular thing that was difficult. Like everybody else, when we came to the long scene with the father and the son, where the father gives him advice, which is a very, very, very long scene. It was longer in the book than it is in the movie.

I knew that never ever put at the end of a movie a long dialogue scene because people don’t want to listen to it, they want to get up and go. And here we were putting this long, long, long very, very important dialogue scene at the very end of the movie. I worried about that constantly. But it wasn’t a difficult thing to write somehow, and I liked imagining certain new scenes, and the whole business of finding the statute in the water was all new. That wasn’t in the novel.

There wasn’t really any difficult thing. But I wasn’t there for the shoot. I imagine they shot stuff that was in the script and then because the film was so long, they cut it. Or maybe it was too expensive to shoot. There were sequences which probably they didn’t want to spend the money on.

Q: Why didn’t you direct it?

JI: Well, Luca Guadagnino decided he wanted to direct. Then he wanted me to co-direct, and I said I would. Though I don’t think I would have been allowed to do that, because the Directors Guild just absolutely will not allow people to co-direct. You don’t do it.

It was a French-Italian co-production, and they thought it would be a terrible awkwardness and the possibility of trouble if there were two directors. What if they got into a dispute over something, and while they were disputing, valuable time was lost and everyone just sits around. You can’t resolve something that you don’t agree about, and so on.

And how would it look, also, if one of those directors had to give up and the other one would then be the “real director” in people’s minds. It was an awkward thing. I think that’s what happened.

But I didn’t know it was going to happen because just before Luca went back to Italy to make it, I had a meal with him in New York. I said “What are we going to do if you and I get into an argument on the set?” He just laughed. “Oh, it won’t happen,” he said. “So what?” But I think that was in the minds of the financiers, the possibility of that. And then, maybe, in Luca’s mind, too. He would not have liked to back down on something.

Q: Shia LaBeouf was supposed to be the Armie Hammer character before Armie Hammer came in.

JI: Shia LaBeouf was cast in that part, yeah. And Greta Scacchi was going to play the mother, which was my idea. I don’t think Luca was all that happy with it. But she would have been perfect because she was fluent in Italian and she had an Italian passport. And to have a big part in that film, you had to have a European passport.