The Film Tom Petty, Somewhere You Feel Free Debuts at SXSW 2021 To Acclaim

October 2, 2017, it was devastated to hear the announcement of Tom Perry’s untimely death, one week after the end of the Heartbreakers’ 40th Anniversary Tour. At that time in his career, he had sold more than 80 million records worldwide, making him one of the best-selling music artists of all time. Petty and the Heartbreakers were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2002.

Formed in 1976, he was lead vocalist and guitarist of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers; previously led the band Mudcrutch, and was also a member of the 1980s supergroup the Traveling Wilburys.

Petty recorded a number of hits with the band and as a soloist With the band they charted such songs as “Don’t Do Me Like That” (1979), “Refugee” (1980), “The Waiting” (1981), “Don’t Come Around Here No More” (1985) and “Learning to Fly” (1991).

As a solo act the hits included “I Won’t Back Down” (1989), “Free Fallin‘” (1989), and “You Don’t Know How It Feels” (1994).

Daughter Adria discovered a stash of 16mm film shot by photographer Martyn Akins between 1993 and 1995 chronicling Petty’s recording of his 1994 triple platinum album, “Wildflowers” — which he considered his best and most personal. The found footage, along with insight and perspective from many who were there, form the basis of this feature directed and produced by Mary Wharton, an experienced music doc creator.

Q: What was your relationship to Tom Petty’s music and how did you get interested in his story?

MW: I’ve been a fan of Tom Petty’s music since the late ’70s, early ’80s. I’ve been a music geek my whole life. My father is a musician and he used to always bring home records of new artists. I remember hearing Tom Petty as a kid and just loving the very classic guitar rock-and-roll sound that he had.

When I decided to pursue becoming a filmmaker, I started my career working in television, actually. I worked at VH1, the music channel which is part of MTV; it was the sister channel to MTV here in the United States. I had just started my career, and a couple years into it, I got a job working on a documentary about Tom Petty in 1994.

It was around the time that he was about to release his “Wildflowers” album. I knew that record because I worked on this film and saw Tom Petty on the Wildflowers Tour when he played at Madison Square Garden in New York City. I got to go to Los Angeles when the filmmaker who was making this particular documentary was doing an interview with Tom Petty and I got to go and help him that day. I was in the room and met Petty and got to have my picture taken with him as a young lady. That was a pretty big day for me!

Pretty big and very much an amazing learning experience, because I was working for someone who was really mentoring me, teaching me about how music documentaries are made. That was a foundational experience for me as a storyteller.

It had been some 20-some years later that this project came to me, and it was such a full circle moment. I was able to look back at who I was all those years ago and what I hoped to do with my life, and then here I was, doing it — doing what I had always wanted to be able to do. That it be a film about Tom Petty was the icing on the cake.

Q: In early 2020, this footage was discovered in Petty’s archives that was never seen before. How did you decide to intertwine this archival footage with that of the Heartbreakers members? How much of that found footage is there?

MW: The discovered footage of these recording sessions is about four hours of material. In addition to that were the things like the scenes of Tom in his backyard with his dog.

And they shot the Wildflowers tour, three different performances. There was one that opened the tour in Louisville, Kentucky; there was one at Hollywood Bowl, and then there was also a New Orleans, Louisiana, show that I don’t think we ever had transferred. But I would guess there was about another three or four hours of tour footage that we had available to us.

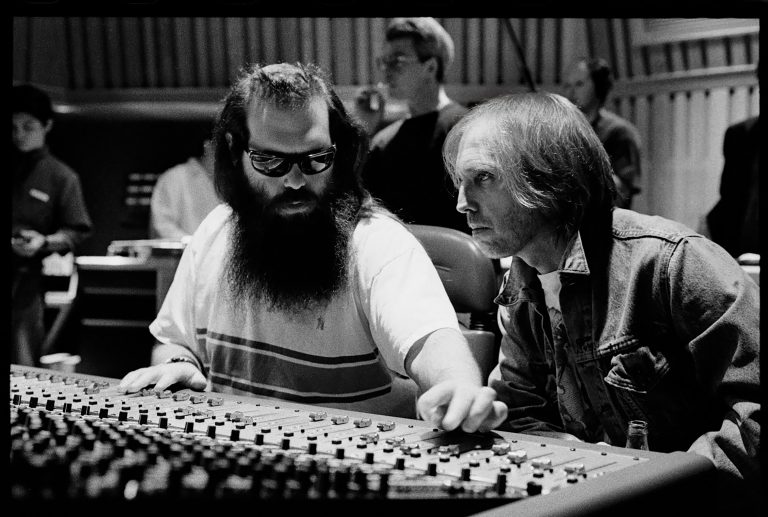

And then there’s conversation with Rick Rubin, Mike Campbell and Benmont Tench that was shot in black & white. There’s also the Rick Rubin black & white interview. That was filmed by Petty’s daughter Adria at the very beginning of this process, when she knew that they wanted to make a documentary using this archival film. She was able to set up a time when those three guys all happened to be available on the same day in the same city.

They hadn’t quite figured out who they were going to bring into this project as a director. They had started talking to me about it and I was very much interested in it. I encouraged Adria to just go ahead and shoot this conversation, because I knew that it wasn’t going to be easy to get Rick Rubin, Mike Campbell and Benmont Tench all together.

I joked that Rick Rubin was like a Yeti, a mythical creature in a way; if you can capture him, get him while you can. And I was able to listen in. I had a Zoom link where I could see a feed from the camera to see what was being filmed, and I could text Adria with followup questions or things to ask.

When Adria decided to go ahead with that shoot, she made the choice to shoot it in black & white, because of the fact that all of the recording studio footage had originally been shot on black & white film. She thought it would look better to marry those two things together. I have to give her credit for that decision.

But it was such a brilliant decision, and when I came in to the project and decided to shoot the interviews with the Heartbreakers, I also wanted to shoot it on 16mm film so that it had the richness of grain and texture of film, to give it that subtle kind of feeling that would make it blend well with the archival material.

I had a feeling that we might make it black & white, but I cheated a little bit. I was like, “I’m going to shoot it on color film, just so that we have the option: you shoot it in black & white, it can only be black & white. But if you shoot it in color and you decide you want it to be black & white, you can do that in the post-production.

When I got the color film back, it was so beautiful that I was like, “you can’t turn this black & white. To have this whole feature-length documentary all shot on 16mm film is so rare in this day and age. Digital video is beautiful, but doesn’t have that rough-around-the-edges feeling that film does: you see the full frame of the film and there is like, junk around the sides and the edges are not clean and sharp, and there is grain and scratches and dirt and hair in the gate and stuff like that. I just love that, it feels very nostalgic. The fact that this was a nostalgia-riddled project made shooting on film the perfect choice.

Q: Tom Petty’s first solo album was Full Moon Fever (1989) and it was quite successful. By then he was working with the Heartbreakers for almost 20 years, the same people all the time. He felt like he had never grown, in a way. That’s what he said in a movie. He wanted to get out of his comfort zone, to achieve something different. He was obviously succeeding as an established artist, but at the same time struggled to step forward. So what was his mental state back then?

MW: One of the things that was surprising to me was this idea that Tom Petty could feel trapped. You would think that his success would give him whatever freedom he wanted. That’s your notion of success, right? “Well, I can do whatever I want because I’m Tom Petty.” And in some ways, I guess, he probably could have. But he felt trapped creatively, by, “if I just keep working with the same people I’ll never progress beyond what those people and I have together.”

He also felt a little trapped by his record label. He had battled with his label for a while over lots of different things — over the prices of his records. He wanted to keep prices low so that his fans who weren’t rich could afford to buy his music, so he kept his ticket prices low. He was always fighting for the little guy.

I think that he felt like he carried a lot of responsibility for his family, for his band, for not just the band but the crew [as well]. He probably had 40 people on the payroll of the business of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, where he felt a responsibility for all of those people. That was trapping him into [having] to do the thing that was going to make enough money to support this empire that he had built. He had just reached a point where he felt like he wanted to give himself permission to follow his creative muse.

For a songwriter like Tom Petty, it’s the idea he had to “create or die.” For a creative person, if you don’t feel you’re challenging yourself, you don’t feel you’re growing as an artist, then you feel like you’re dying. He was at a point where he knew he had to make some really big changes, and I’m sure that was scary for him.

That’s one of the things that was the most interesting to me about diving into this archive of film and learning about what was going on with Tom Petty and learning this part of his story: to discover how human he was. I always looked up to him like a rock god, if you will. As a kid anyway, I always looked at rock & roll musicians as somehow very much “other.”

It’s really remarkable to see Tom in this way, where he’s not always sure of himself and he’s finding his way in life, in his art and discovering new things about himself as he goes. It’s a pretty incredible opportunity, to see that.

Q: Producer Rick Rubin established Def Jam Records with LL Cool J and the Beastie Boys’ single. Then on to Red Hot Chili Peppers and Mick Jagger, AC/DC and so forth. In the movie, he’s not a corporate man compared to other producers. Yet he becomes head of Columbia later on. So that’s ironic.

What do you think was [Rubin’s] quality that Tom decided to work with him? He doesn’t play an instrument, but he definitely loves [Petty’s] music.

MW: It seems like it was his youth that made him intriguing to Tom.

Q: How old was he when he worked with Tom? [Around 30]

MW: I don’t recall exactly. But I just know from what Tom said about him. He said, “We’ve never worked with someone who was younger than us.” Tom was about 40 years old [44] and he was trying to figure out how to be a rock & roll star but with some dignity. He was looking around, and if you think about other artists that were popular in the ’90s, you had artists like Guns ‘N Roses who were out there with debauched lifestyles, with their shirts off all the time, and that kind of thing. That very obviously was not Tom Petty. He was not that guy.

But he was also an older — well, 40 seems young to me — so he was trying to age gracefully and still maintain his rock star quality. Rick presented a certain amount of young attitude towards music but with respect for the past, and respect for the kind of dignity that Tom Petty carried himself with. Tom was a very dignified man.

Rick had a really great — perhaps the perfect combination of being in touch with what was going on in the moment with younger artists and young audiences, while having the ultimate respect for the past. It meshed really well with what Tom needed in that moment.

Q: Wildflowers was originally supposed to be a double album, but it was decided to make it a single album after Warner initially rejected it. How many songs were there initially before they cut it down to the single album?

MW: They had finished and mixed 25 songs that would have been fine to put out. And then they ultimately had to cut it down to what would fit onto a single CD. If I remember correctly — I don’t have the final track list in front of me — I think it ended up being 17 songs on a CD. For example, one of the songs that they had to leave off was “Hung Up and Overdue,” which had Ringo Starr playing drums and Carl Wilson of the Beach Boys singing backup vocals. It’s amazing that it shows you what an embarrassment of riches they had that they could leave something like that lying in the dustbin of history, essentially. But that was also a very long song — it was 6-1/2 minutes long or something like that, so it was not going to fit onto the CD.

But I think the reason, as best I can figure out — and there have been a few theories put forward — but the thing that makes the most sense, at least from Adria’s perspective, was that if they had put it out as a double record, it would have been expensive for fans to buy. It might have cost like $15 to buy a single CD, but it might have cost them $30 or $40 for a double CD set. That was always something that was really important to Tom, to keep things affordable for his fans. So that makes sense. He talks about that in one of his interviews. We used a little clip of it, where he says, “it would have been really expensive to buy so we just decided to cut it down.”

But that was definitely a difficult decision for him, and even more so to figure out what to cut off and what to put out. That was important to him: the sequencing of the album. It’s something I never really thought about until I started making music documentaries, but when you listen to the songs in the order that the artist intended, there’s an arc — it tells a story. The songs are like chapters in a book.

As much as I’ll listen to albums as songs that I particularly like out of order, I like to at least, one time, listen in the way the artist intended, just to have that experience.