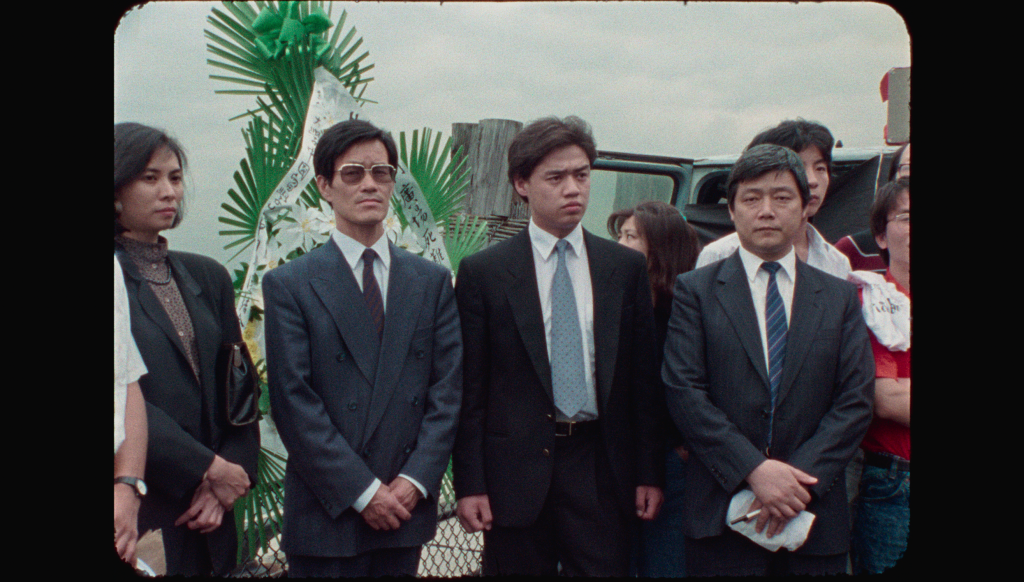

Synopsis : Documentarian Christine Choy tracks down three exiled dissidents from the Tiananmen Square massacre in order to find closure on an abandoned film she began shooting in 1989.

Directed By: Ben Klein and Violet Columbus

Produced by Maria Chiu, Ben Klein, and Violet Columbus

Executive produced by Steven Soderbergh, Chris Columbus, Eleanor Columbus

An Exclusive Interview with Documentarian Christine Choy on “The Exiles”

Q: Co-directors Ben Klein and Violet Columbus seems to have been following your career for a quite period of time. At what point did the subject shift to the Tiananmen Square protests? Then, the film focused on three of the surviving leaders of Tiananmen Square protests, and in the film, you said, “Rediscover yourself through your film,” was that your intention behind that?

Christine Choy : Violet and Ben were my students 5 or 6 years ago. After they graduated, I had told them of the recently found1989 footage. They approached me with the idea of making a film about me revisiting the project and me revisiting the exiles who were still around.

Q: When you made this wonderful film, “Who Killed Vincent Chin?” you were nominated for the Oscar, when there weren’t any Asian members back then. How much has progressed when it comes to Asian voices, what do you think is still lacking in the film industry?

Christine Choy : Within the last twenty years I have seen a lot of changes within the Oscar’s organization in terms of growing diversity and representation. We have seen significant progress with African American, women, and LGBT filmmakers receiving bigger roles and more recognition. I do believe however we are only beginning to see the progress with Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Latin Americans

Q: You were working in Los Angeles, shooting for HBO, when the Tiananmen Square protests happened. What was your impression from both a filmmaker’s perspective and also as seen through the eyes of an Asian American?

Christine Choy : When watching the initial protests, I was under the impression that the event would be over in a few days. While I was unsure of how it would resolve itself, nobody, including myself could foresee the impact such an event would have both culturally and geopolitically.

Q: From the beginning of the Tiananmen Square protests, the protesters clearly were not trying to take down the Communist Party. They wanted to reform it or for the government to hear their voices. Do you think the massacre could have been prevented, depending on how the student leaders approached this protest. Even though the students never doubted that their own government could kill them or with the military’s presence there, that they would have no choice but to open fire like that. Did the leaders talk about their approach to the protest?

Christine Choy : Absolutely not. There was nothing the students could have done to prevent the massacre unless they stopped their protests. Remember, these protests were peaceful and non-violent. Chinese citizens do not have the right to bear arms, meaning their protests were less about violent conflict as it was about sending a message to other potential movements that they will be wiped out. The leaders of the movement, were adamant that mass gathering of support and peaceful protests would be enough to get the world’s support.

Q: The Chinese government concealed the number of deaths when the Tiananmen Square massacre happened. It’s still unknown how many people died. The government never released the exact figures to this day. What scares me about that, in this era of digital communications that we are living in, how could the government still conceal anything, and how did people allow it to happen? I was even surprised by the Chinese exchange student that you spoke to, how much she was afraid to talk about the Tiananmen Square protests in front of the camera.

Christine Choy : Go ask the Chinese government.

Q: You had an opportunity to interview some of the leaders of the Tiananmen Square protests in New York when they escaped China becoming politically exiled individuals. I was really surprised that you held onto those interviews for a long time. Of course, they never expected that they couldn’t go back to China for such a long time, but knowing the One Child policy and all those other policies in China —how strict they were back then — neither they nor could predict that they couldn’t return? Then did you realize the growing value of the videos you made?

Christine Choy : I had always realized the value of the footage I had. Unfortunately, after the funding was pulled, there wasn’t much I could do with it. In fact, I have offered the footage several times to Shanghai TV, who wanted nothing to do with it. In fact, they told me to never mention the footage to anyone. Thus, it all sat in storage for years until I was able to convince Ang Lee to fund the restoration of the footage. Once we realized how clear the footage and sound were, we were inspired to continue the project. Given the recent controversies surrounding the Uyghur population in china, it felt the perfect time to reexamine the footage, comparing 1989 to today.

Q: One of the leaders, Wu’er Kaixi, surrendered himself after living in Taiwan for a long time, not having gone back to China to see his family. He spent the night in an immigration detention center in Macao, but they never accepted his surrender because it didn’t take place in China. I found a unique way to commemorate the June 4th event. Is there more significance than that to his surrender?

Christine Choy : Despite being on China’s most wanted list, the CCP refused to accept his unconditional surrender. This is because it is easier for them to censor his existence within China than it is for them to face the internal scrutiny of his returning. Given that the position of the CCP is that the event had never happened, I’m sure acknowledging his surrender would legitimize a movement that was supposed to have never have happened.

Q : They fought for the democratic society at the Tiananmen Square, but in China, the government still leads by communist party where they still control what people say or see on the internet or papers. Now, all of the leaders can freely express their feeling where they live in, and we can hear their voices in many mediums, even in the film. But their voices cannot be heard in China just as the film probably won’t come out in China. I was just wondering how those leaders measure their happiness by returning to China or staying where they live knowing all this above? The word, the exiles always associate with unhappiness?

Christine Choy : Nope, they will never go back to China, yes, many many famous leaders in the world were exiled, mind you, including Kim Il Sung and Li Son Mang since your country( Japan) did not allow the independence movement in Korea, so the revolution was based in Shanghai. So was Ho Chi Minh, who was in Paris. BUT, not for such a long time like these exiles.

Q: Even though this isn’t your directorial film, are there elements that you found fascinating to Ben and Violet’s direction; is there anytime that you suggested something to them as far as their directorial approach?

Christine Choy : The generational differences between us showed me how different film making is today. When I was a director, I was working with film, meaning that every shot needed to be planned out in advanced. Today, with the use of digital, Ben and Violet were able to film significantly more footage than I was able to. Therefore, they had the difficult decision of going through 300 hours of footage to produce a 90 minute doc. For me, it is interesting to see the differences in the directing process today.

Q: What did you rediscover about yourself in the journey that started almost 33 years ago?

Christine Choy : I’m still crazy.

Here’s the clip of “The Exiles.”