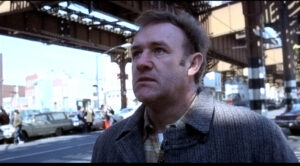

Mississippi Burning, 1988

Released in 2004, Welcome to Mooseport by Donald Petrie is a comedy not many people remember. And they are quite right to do so. It is important because it’s the hundredth movie that credited Gene Hackman as an actor. When he reached this impressive milestone, he decided his job was done. He retired without any official statement, not a word. Without glamour, the same way he carried his entire acting career. For him it was surely the chance to express himself, but most importantly it was a job. This is why Hackman has done, together with Welcome to Mooseport, tons of forgettable movies. With some others instead he wrote the history of American Cinema starting with the “New Hollywood” artistic revolution. From July 25 to July 31 Film at Lincoln Center presents Gene Hackman: A Week with the Gene Genie, a retrospective of 18 movies that shows the actor’s work over the decades, especially his absolute versatility.

How to explain the common link that ties the selected titles? With a simple word: respect.

Respect for the character first: watching any of these movies you can easily understand that Gene Hackman never put his personality in front of the role. In his breakthrough performance as Buck Barrow, Warren Beatty’s brother in Bonnie and Clyde (1967) by Arthur Penn – for which he received his first Academy Award nominee as supporting actor – he embraces perfectly the flamboyant, almost hysteric mindset of the criminal, and in a few scenes is capable of developing a larger-than-life character. Three years later Hackman achieved a second Oscar nomination in the same category for a completely different character in I Never Sang for My Father (1970) by Gilbert Cates. His role of a son struggling to leave behind the shadow of an authoritarian father (Melvyn Douglas) is played with a few, precise touches, and still enough to make the audience understand his conflicted inner life. In these first movies you can already understand how Hackman had devoted his professional life at the service of the project, wholly understanding what was needed from him in order to elevate the final result.

He wasn’t the first choice of William Friedkin for the role of Jimmy ‘Popeye’ Doyle. Not even the second or the third. And he struggled for weeks with a character that he thought at the beginning too rough, too violent. But then again, Gene Hackman was fully committed to do everything required in order to make his roles layered but believable, so he put his craft to the service of Friedkin’s vision, and trusted it to the bone. The French Connection (1971) changed the rules of shooting and created what we perceive as contemporary noir. Gene Hackman’s performance is regarded as one of the best and most important in the so-called “New Hollywood” era, definitely one of the most effective in portraying the reality of what was going on in the United States – particularly in New York – at that time. If we consider how far Jimmy Doyle’s personality was far from the lifestyle of the artist who gave him life on the big screen, you can really understand the greatness of that performance.

The French Connection, 1971

Once he gained the “star” power to pick the roles he wanted, Hackman used it in a series of movies that depict the struggle to understand American society and way of life, something highly prominent in the early ‘70. In movies like Scarecrow (1973) by Jerry Schatzberg, The Conversation (1974) by Francis Ford Coppola and Night Moves (1975) again by Arthur Penn, we can see Gene Hackman’s characters dealing with a world which hides violence and betrayal under its surface, a world that these men try simply to navigate, failing to understand its rules and complexity. The Conversation – voted by many critics as the best movie of the ‘70 – is one of the most complex and pessimistic takes on what hidden forces rule American society, a sort-of dystopian thriller that Hackman elevates with his composed, almost reserved performance, exposing with perfect physical and psychological adherence Harry Caul’ s disorientation. A character that he would re-enhance (named this time Edward Lyle) almost 25 years later in Enemy of the State (1998) by Tony Scott.

The Conversation, 1974

Watching Gene Hackman’s work all over the years you can fully understand how, no matter what movie he was acting in, his belief was: get the job done. And no title like Mississippi Burning (1988) by Alan Parker exposes that with such power: in the role of the experienced FBI agent working with the boss Willem Dafoe in order to solve the murder of three activists in 1964, Hackman gives Rupert Anderson’s character a practical vehemence, a contained disdain that make him not the hero you would want beside you, but the law enforcer you need in a time like that. After the glory of the ‘70, Mississippi Burning represents in our opinion the best performance of Mr. Hackman’s career, maybe the best at all. Even better than the one he gave to Clint Eastwood for his crepuscular western Unforgiven (1992), a masterpiece awarded with the Oscars for best movie, best directing, best supporting actor (Hackman of course) and best editing.

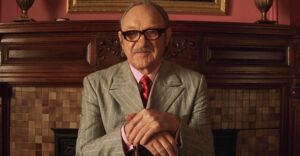

When Gene Hackman wanted to let himself go, he was capable of a histrionic, hilarious performance. His biggest box office hit in the ‘70 has been Superman (1978) by Richard Donner, where he plays a joyful Lex Luthor, clownesque without any make-up, threatening but always with a smile on his face. A role he would play again in the 1981 sequel with the same levity and elegance. He could be absolutely funny even inside an austere role, like he demonstrated in The Birdcage (1996) by Mike Nichols, where he starred together with Robin Williams and Nathan Lane. Not to mention of course his legendary cameo in Young Frankenstein (1974) by Mel brooks. But when we think about Gene Hackman and comedy, the title that comes first in our mind is The Royal Tenembaums (2001) by Wes Anderson, where he plays the carefree and sailfish patriarch who destroyed the family life and messed up his children’s psychological life without even knowing it, too immersed in his luxurious and extravagant universe to be really aware of anything but himself. His Royal Temenbaum is a horrible father-figure that still you can’t stop loving, because of Anderson’s magnificent writing and because of Hackman’s performance, a scrupulous portrait of a man haunted by the fear of silence and boredom.

The Royal Tenenbaums, 2001

We are not going to talk about how Gene Hackman died last February, first because we have no interest in pointless speculations but most importantly because we value the way he lived, the way he conducted his life through his job.

Watching Gene Hackman starring in a movie – any kind of movie, not only the good ones – meant to see an actor showing not only his incredible craft, but primarily his sense of respect for the job itself. In this case we call it a job because that’s how he perceived it, valued it, and through this lens he was sometimes extraordinarily capable to turn it into art at the highest level. As we already explained in our article about Jack Lemmon, it takes one kind of an actor to make an ordinary character and turn it into a performance impossible to forget. Hackman was capable of portraying the depth of the common man. Not like Lemmon his doubts or fears, but his strength and his tenacity. A man whose goal was always to get the job done, and he did it like no other.

This was Gene Hackman. Do remember him this way.

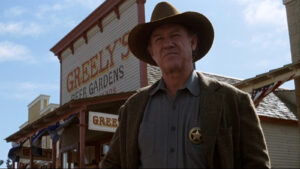

Unforgiven, 1992

Unforgiven, 1992

If you like the articles, share your thoughts below!

Check out more of Adriano’s articles.

Here’s the trailer for Mississippi Burning: