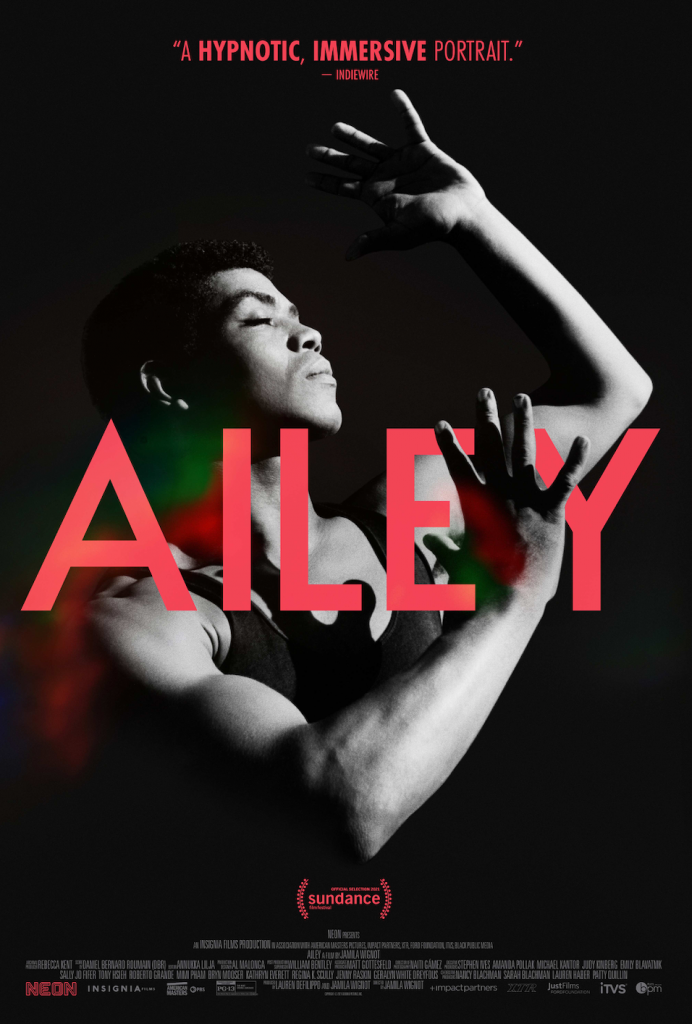

Alvin Ailey was a trailblazing pioneer who found salvation through dance. AILEY traces the full contours of this brilliant and enigmatic man whose search for the truth in movement resulted in enduring choreography that centers on the Black American experience with grace, strength, and unparalleled beauty.

Told through Ailey’s own words and featuring evocative archival footage and interviews with those who intimately knew him, director Jamila Wignot weaves together a resonant biography of an elusive visionary.

An Exclusive Interview with Director Jamila Wignot

Q : When did you see the Ailey production for the first time and what inspired you to make this film?

JW: I first saw Ailey’s production in college. I didn’t know anything about the company and hadn’t seen any modern dance before. And so I entered the theater with no expectations and just really had my mind blown. I think I was this visceral nature really spoke to me, and of course, this kind of centering of regular life that gets dramatized in a satirical way on stage, I just found it incredibly beautiful. That memory stayed with me and I remained a fan ever since. Then, when I was approached in 2017 by insignia films, they were searching for the director, I got lucky.

Q: Do you have any dance background?

JW: I have no dance background. I love to dance and did drill team and cheerleading but I have no formal training.

So it was a really important part of my research process, to really steep myself in dance tradition to find the best way to showcase the dances that we feature, so that they would be seen as powerfully as they could as mediated through film as they do in an evening.

Q: You did a beautiful job. How did you manage to put the story together about his pioneering works to main stream?

It shows Ailey was an icon and true artist. But he has vast works that you need to tell. How did you make his story in less than 2 hr, what was the starting point?

JW: That’s the heartbreak. At the very beginning. You know you’re not going to be able to come close to curating all dance works that he created. So we were limited by what actually filmed; that was beyond our control. And then we were guided by these audio recordings that he conducted from 1988 to 1999. In the last year of his life reflecting back on his life and what informed his process; what was drawing him to be called to dance and what he offered as an expressive form. And then the other part of that, we had shown this contemporary thread, so looking for the thematic connection translating from Mr. Ailey graphical serial that we had, and sort of layering all these together.

Q: How did you decide to have this contemporary dancer from Alvin Ailey’s American Dance Company? Is it to show how his spirits kind of passing down to the generation?

JW: From the beginning there was always an awareness of Mr. Ailey’s legacy lives on so vibrantly, I always tell people, if you had an opportunity even walk into the dance company in Manhattan. There is that energy, people move and walk into that building and something of him, it’s literally alive there. It felt that a portrait of him would be incomplete, if it only contained the years he lived. It acquired a sense of what he left behind.

Knowing that, when we approached the company we had asked for a contemporary glimpse into the company today without having a real sense of what we wanted to do. We just wanted access. The artistic director said we just commissioned Rennie Harris to do this hour long ballet on Mr Ailey’s life and times for the 60th anniversary. So that was just this kind of serendipitous happened and we’d be grateful if we can be involved with that process — that would be wonderful.

Q: I was surprised that with all those people that he worked with, he did not have a specific partner for a long time. It must be tough for him to lead the company, so how he maintains his inner struggle while he’s also running the company at the same time?

JW: The duality shows. It’s one of the things that I could take away from the intriguing aspect was that, he could be so giving; he was one of those people who could cast a light on everyone all around him but never allowed the light to be truly shown back on him. I think it’s just an interesting conundrum in some way. At the same time, he required this deep privacy but at moments in which he wanted to create intimacy of a romantic nature like what he had with Abdullah, so it was lost to him there was an even very poignant moment where I wanted him to remain on a pedestal, he arrived at a place where he was loved as a father figure an icon and leader, so I think that’s an interesting aspect to him.

Q: By shooting this documentary, what elements separate Alvin Ailey’s American Dance Company from other dance companies? What stood out for you?

JW: I think really the mission from the very beginning was that, unlike every other choreographers of his day, he was not only creating a company that would dance his own works be a reflection of his own expression alone. He always saw Ailey as something that would perform dances that came before, it would open up that opportunity for younger choreographers to harness that. In our stories, so many others, like Bill T. Jones was offered a chance for a stage work, which got a national attention. Today, Rennie Harris is doing that legacy.

That generosity he always saw the company as being something bigger than himself in many ways.

Q: What was the most surprising element in this production — seems lots of elements you discovered?

JW: I think of his vulnerability and loneliness in his life for the reasons as we discussed. The way people talked about being around him, the all embracing quality came back to him the fact that he did need… It was surprising to me. At the same time, for a person to say I’ll sacrifice all things for dance, as space to be just made sense. If he were alive today, I’d just love to talk with him more about that.

Q: After we go through pandemic and Black Lives Matter, do you think we have different reactions to this film if you made this film a decade ago? There’s an appreciation of black culture now; there’s another film like, ‘Summer of Soul‘, which won the Sundance, it was also embracing the black culture. It was perfect timing for this film to come out.

JW: Both of our films… A decade ago we couldn’t have made them. We couldn’t have had access to the archives, it’s so foundational in different ways. Summer of Soul couldn’t get that archive at all. People were aware that it had been preserved and existed in that … Similarly, the way that we were able to do, there’s a world that we built that Mr. Ailey inhabited that we get into everyday black life that 10 years ago that would not be possible.

I’m in a place where I want stories about — I understand that there is the social movement for justice and the politics and the fight we still need to wage — but at the same time, it was important to see Mr. Ailey’s works for the first time. Oh, right beauty and joy and love and caring and family and fun and that there is a tradition, those are the things that make up a people. There is drama that isn’t about our perceived brutalized or marginalized by white superemacy structure. I think Both films are a showcase that in a way allow people to get into a space of the times that we are in for sure.

Here’s the trailer of the film.