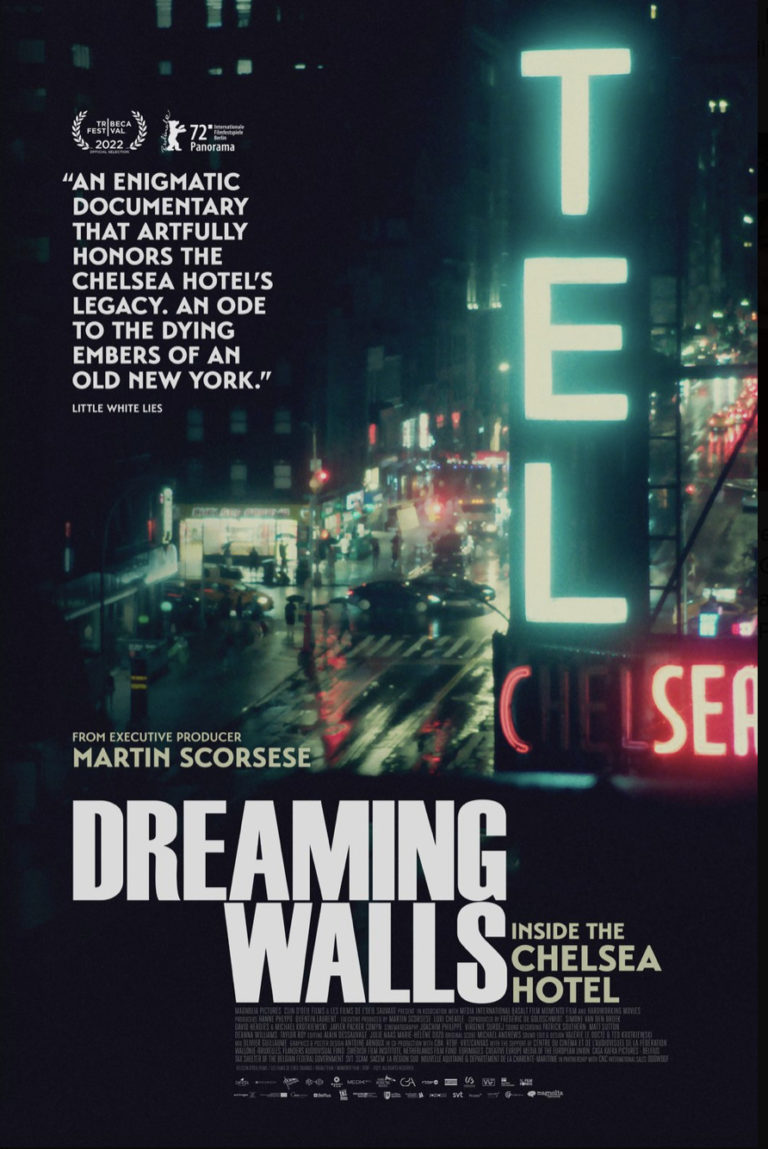

Synopsis : The legendary Chelsea Hotel, an icon of 1960s counterculture and a haven for famous artists and intellectuals including Patti Smith, Janis Joplin and the superstars of Warhol’s Factory, has recently reopened after extensive renovations, which are now almost complete. Dozens of long-term residents, many in their later years, have lived amidst the scaffolding and constant construction for close to a decade. Against this chaotic backdrop, DREAMING WALLS takes us through the hotel’s storied halls, exploring its living body and the bohemian origins that contributed to its mythical stature. Its residents and the walls themselves now face a turning point in their common history.

Exclusive Interview with Directors Maya Duverdier and Amélie van Elmbt

Q: After you read the book, “Just Kids” by Patti Smith (2010), it led you to make a documentary about the Chelsea Hotel — why was that the case?

Amélie : Actually, the book was a gift that Maya, as a friend, gave me 10 years ago, before we encountered the Chelsea Hotel. The way we really encountered the place was not linked directly to making a film. It’s just how we got to know the place. That’s why we recognized it when we were on 23rd Street for the screening of my film.

Then we both added a knowledge of the place because of our friendship, our relationship. It was all linked. But it was by chance that we happened to meet the building again in real life. That’s it.

Q: There are many stories of such famous people as Leonard Cohen, Patti Smith, and Andy Warhol being associated with Chelsea Hotel. I believe Arthur C. Clarke wrote “2001: A Space Odyssey” there. The Sex Pistols’ Sid Vicious’ girlfriend Nancy Spungen murdered in the hotel. But instead of covering its cultural history, your film focuses on the present. Why did you make that decision?

Amélie : It was very important for us to capture this moment in time for the Chelsea Hotel because we didn’t know that it was being transformed into a luxury place. Most important for us was to capture this moment, and also to trace the lives of those artists who were in the shadow of the bigger names. They were actually not really known, and they are part of the history of New York, so it was super-important to keep trace of them.

As you might know, the Chelsea Hotel has already been filmed many times, and there are a lot of films about the place that only talks about its glamorous history and the myth of the Chelsea, so we didn’t want to make the same kind of film.

We really wanted to tell the story of the ones who were never put up front and who are really, we’d like to say, the fertile soil that gives the others a place to emerge. Without this soil, all these different kinds of social backgrounds, creative backgrounds, people, even the ones that are still in the film and didn’t succeed to be in the spotlight, they were really the ones that make the others emerge.

It was so important for us to also keep traces of that and not tell the story that we already know, like Warhol and all of those people that there [is] so much documentation. Of course we tribute them with evocation in the awards, but it’s not a tribute to them. The film is really a tribute to those artists that we love and we share so much with, and we wanted to really put in front.

Q: In the movie, you meet a woman named Mel Easter, who showed you around the hotel. How did you gain the access and trust of those people so that eventually opened up to you and became friendly?

Maya : Mel was the first person we met when we entered the hotel for the first time. She was just sitting in the lobby, as she used to do every day. When she was with us, she began to talk. Maybe it was our chance, in a way, because if she [had] not spoken to us, we would have been kicked out like everybody [else], because Chelsea Hotel was closed to the public.

But she started to talk [and] we were getting on well with each other. Then Amelie invited her to see her movie in the theater. She came, and was super-happy, so she invited us back to her room to thank us. That was the first time we really entered the place. We discovered the situation and everything.

Then we had a lot of time with Mel, and we began to know her more and her story, but also more about the place as well. She introduced us to other people, and then — we never knocked on doors — it was always that people heard about our presence and were curious about us as we were curious about them.

So it was a very, very natural and organic process.

Amélie : If I can add something: we didn’t plan to make a film. It’s not like we came to Chelsea on purpose or that we needed to get something from it. It was really an encounter, and the idea of the film came later.

I think they believed in us, trusted us, and they saw that we kept coming back. We were not trying to just capture their story but to spend time with them. That’s how we gained their trust, I think, because of this approach. Then we also started with an old 16mm camera.

Q: You talk about a really grand hotel tour that we see through all those people. It seems like you were taking a long time to digest each story. So how difficult was it for you to put them together and how long did you take to shoot this — did you actually map out the storyline?

Maya : We wanted to make a long-process documentary where we were going back and forth which was really a challenge for us in shooting, and that lasted two years. It was two years of shooting with a team, and then one year of editing; and post-production, one year, let’s say. It was two years of shooting, but the whole process took four years. Yeah, what can I say? We didn’t want to make everything just a first closeup shot and then…

Amélie : We really meant like two weeks or three weeks of shooting. Then we came back to Europe, looked at the material, and spent two or three months in Europe wondering about what we had. Investigating the place and then coming back. And it was… It felt like two years and enough, I was there.

But even during the pandemic, we were shooting with a remote team. There was really one year when we were only editing. There was still time for shooting one scene through remote shooting, so we never really stopped. But in total, it’s like two years working with the people on it.

Q: This is not like a regular apartment building. Some residents have gardens on the roof, and some have animals. Since this is a hotel, how did the manager Stanley allow it?

Amélie : It was really the opposite of what can be found in the hotel now. I think Stanley [Bard, son of one of the owners of it during the 20th century] really curated the place. He was choosing the people he wanted to have in the hotel. He took money from the wealthy, but he also gave spaces to artists like Patti Smith who didn’t have any money at the time.

He also decided sometimes [according to] the face of a person or the feeling he had about them. But some that he loved, he really gave them a lot of trust. It was really a question of trust, and a question of trade also. He was trading some rooms for some piece of art, you know?

There are so many stories — we couldn’t put everything in the film. But we know that at one time there was a tiger there for some contemporary dance by Katherine Dunham, who was a great African -American dancer and choreographer. She came to the hotel, and sometimes asked Stanley, if she could bring a tiger into the hotel. It did happen, so it’s even more than what you saw in the film.

There was the collection of Susan Kleinsinger, wife of George Kleinsinger [writer of the 1940s children’s classical-music piece, “Tubby the Tuba”], who used to love to have a jungle and Stanley allowed it, because he loved and trusted him.

A lot of strange things happened, and it was only through the consideration and rules of Stanley. In a way, that’s also why at some point he was evicted by the board. Because, supposedly, they couldn’t keep track of what he was dealing with — or dealing. There wasn’t really any clear guidance to that, if you know what I mean?

The other owners, when they discovered that not everything was kept in the books, there were a lot of negotiations and sometimes — as you would know in the press, some accusations of whores, some drugs — it was so flexible that sometimes there is a cost to that. You pay, you know what I mean? But it’s really Stanley who decided.

Q: It has had a renovation for such a long time with new owners now. How did that progress and what is the situation now?

Maya : Since 2016, there’s been three new owners, so it’s a trio of owners who bought it back. So they began the work in a more respectful way than the previous owner, because it happened 10 years ago that people bought the hotel.

There have been a lot, and the first one really was very violent with people at the Gresham. They formed an association to fight the owner.

But now the situation is that those three people took it over and it was hard, but they managed to make the renovations they wanted. There have been a lot of lawsuits and a lot of people were not agreeing with the work in the hotel. So the hotel is divided into different parts. But it’s reopening. — it’s already reopened, actually…

Amélie : Not all the floors are done. They’ve managed to reach the end of the renovation, but there are still some floors where there are workers.

So if you can book the place; if you book a room you will have to be in the basement for the present night.

You can also feel what it’s like to be back at the hotel just before the reopening, but all the restaurants, the communal area — the bar and the lounge — are open to the public.