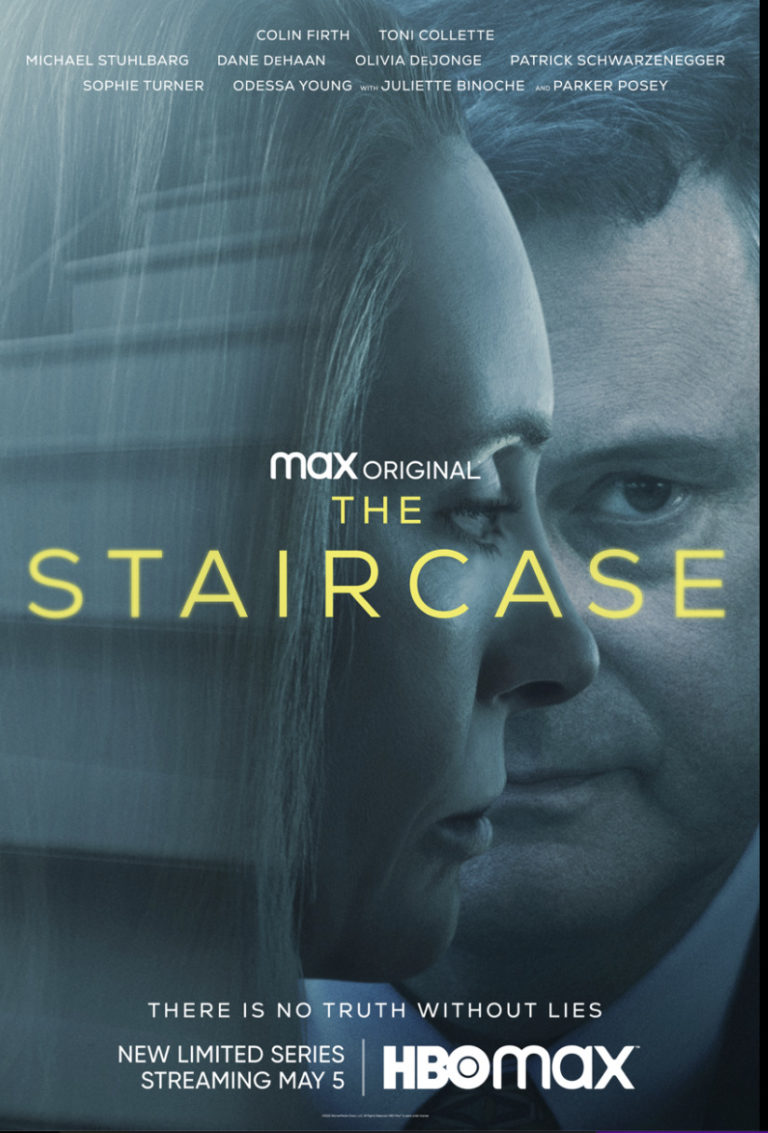

Synopsis : The Staircase follows the compelling story of Michael Peterson, a crime novelist accused of killing wife Kathleen after she is found dead at the bottom of a staircase in their home, and the 16 year judicial battle that followed.

Exclusive Interview with a Showrunner Maggie Cohn

Q: “The Staircase” documentary had a such impact on the crime documentary, since then, there are lot of documentaries, such as “Paradise Lost” series, “The Central Park Five”, what was the elements that you found it fascinating in documentary that made you decide to make this series out of that?

MC: This concept has always been very fascinating to me. And then, when years later Antonio gave me the pilot script and I read it, I really saw the potential for this project to be a series. A series not only about what happened at 1810 Cedar(Where the Staircase Incident Happened), but a series about storytelling, and about the different ways in which a story is constructed, whether or not it is being constructed by a documentary film office, whether the story is being constructed by a defense team, whether it’s the prosecution, whether it’s somebody within a family creating their own narrative about what happened that night. Everyone is looking to fill in the blanks.

For me, there haven’t been many opportunities to explore what I do for a living in the context of the media that I create. So this, to me, was a way to use the documentary’s fascination with the story as our way into a larger sort of thesis about why stories are told in the first place, and how they’re told, and how they’re received. So that’s what made me really inspired to work on “The Staircase”, initially.

Q: Even though the Staircase documentary covers thirteen episodes, there are a lot of elements in this series that totally separate it from the documentary, such as the focus on the business side of Kathleen besides being a wife and mother. You constructed a more interesting perspective that we didn’t see in the documentary. So how did you consciously avoid the same look as the documentary?

MC: Yeah, it’s not as though the documentary avoided them, it’s just not something you would necessarily put into a documentary. You know, whenever you create fiction or write something, you have the opportunity to build and fill the world in a new way. So since we had that tool, we are able to do that as storytellers: Antonio and myself, and the other writers and the other creatives involved in this project.

It means that we get to then look at Kathleen Peterson as a character. Not only does building and casting out as a character change the viewers’ experience when they’re watching our show — than, say, when they watch a documentary — it also allows us to really go into what her absence truly must have felt like. Because in order to understand her absence, you have to know what’s missing, right? In seeing Kathleen and bringing her character to the screen, it perhaps gives us a better opportunity to understand what each of these characters is experiencing in this new world where she’s not with them anymore.

So that’s just one example in the ways that we were able to take the world outside of the camera — the frame that we all saw in the documentary — and build that. And we reference the documentary throughout, but really the documentary is just part of a larger story that we wanted to tell. It’s not “The story”.

Q: This Peterson family is a very unique family. Michael had a previous marriage to a woman named Patricia and they had two sons, Clayton and Todd. While they were in Germany, they met a couple, the Ratliffs, who had two daughters, Margaret and Martha. When Ratliff died, Michael became the guardian of the two daughters. Kathleen had a previous marriage as well, and she had a daughter, Caitlin. So none of their children are biologically related to both Michael and Kathleen. This dynamic has a different perspective in this series. You carefully constructed this family dynamic which is very intriguing.

MC: I think this family, in the sense that any family can be conventional, I guess. I think every family has its nuances. The nuance of this family is perhaps more on the forefront because two of the daughters were under guardianship because, as you said, their parents had passed away, both in unexpected ways. And then you have the sons, who are products of a previous marriage on Michael’s part, and then you have Caitlin, who is Kathleen’s biological daughter.

For us, while we understood those facts, it was exploring the dynamics of love, and of loss, and of the evolving nature of commitment that you can find in any family if you follow their journey for enough years. I think most people, even if they haven’t necessarily experienced a tragedy, their relationship with their parents or with their siblings, if you follow it for twenty years, there are going to be interesting pivots and there is a certain evolution to it.

I think for us it was a way to explore not necessarily the generational, but the way that grief and trauma manifests and evolves over time, and how that shape can feel and look different depending on the year and depending on your personal circumstance.

Q: How did you carefully construct the storyline with Antonio when covering past-present-future? How did you differentiate all that, because it spans a couple of decades, and I noticed that there’re a lot of hand-held shots in the future sequences.

MC: Yeah, it was a larger conversation, and it starts when you’re writing. So there’s writing, “how are we going to approach differentiating these timelines on the page?” Our approach was: if you removed all the dates — minus some obvious continuity errors — it should still feel like a cohesive narrative. We weren’t making sure the story was blocked — this block had its three-act structure, and this block had its three-act structure. It really was trying to maintain that act structure in each episode despite the fact that you had three concurrent timelines.

And we kept using the word “energy”. For me, it’s about sequences and it’s about how the scenes communicate with each other and the dialog that they have. And you can either make that abrupt and a harsh transition, or you can make a smooth transition, but the idea was that the energy that we had, even though they were three concurrent timelines, should still feel like the cohesive energy you would have with a script that didn’t use this device.

So that was our initial approach in terms of writing. My office was covered with note cards, and each timeline had a different color. So I’m making it sound a little easier than it probably was, going crazy and making sure that everything is working in the way it needs to. Because you just need to make sure that a plot and the theme is still present throughout, and you don’t want to lose it too much in any of the timelines.

Then when it came to production, I think it was fairly early on that it was decided that there wouldn’t be a stylistic visual difference between the timelines. We would really be using character and production design to immediately place us somewhere. We wanted to use handhelds in the future to give it somewhat of this ethereal quality, where we didn’t quite realize: is it a dream, is it not a dream, what exactly is happening in the future? Then it was decided that we would have that hand-held until Michael and Sophie [Juliette Binoche] walked through the doorway into the conference room at the courthouse.

And at that point, we would go to our traditional framing in which the majority of the shots are locked down, it’s basically camera movement on a dolly, or on a tripod. We wanted to do that because then we wanted the viewer to realize, oh no, this is very much real, this is very much happening — and it’s actually very pivotal to our show, what’s happening in this conference room.

But I also think that that ethereal quality that we front-loaded the future timeline with in the initial episodes aided us. Because then we have episode eight where, while the camera has a very firm touch, what we’re depicting on the frame has, again, this amorphous, beautiful, lyrical quality to it. Had we not prefaced that with the hand-held movement, it might feel too jarring at the end.

Q: In the first episode, we realized that Michael lied about receiving the Purple Hearts, and he also lied about his injury in Vietnam, in fact, he actually had a car accident in Japan. But at the same time, you also showed Michael is having a birthday party for his daughter. There appears to be a neutral perspective, so how did you balance out the neutral perspective rather than taking a side?

MC: I think it goes to the idea of storytelling, which is I am not sure I think the perspectives that we offer, the majority of the perspectives are not neutral. When you balance all the perspectives out, you create a certain alchemy that supports multiple perspectives. So we don’t skew towards one or the other.

In the writers’ room, we decided early on that no one had to have a firm opinion, and if you did have a firm opinion, that was okay but you had to create space for other opinions. I think for me, that’s just life; as much as we want to be objective and without bias, at this stage it’s hard, sadly, to avoid it. So is it better to ignore it, or to recognize it?

With our show, we were like, let’s recognize bias and let’s ask people. We were going to present “The Staircase” by weighing out the perspectives and making sure that guilt and innocence were equally positioned on the scale, and that we were actually giving the viewers something that they could then look at. And it’s probably most likely that their backstory — the viewers’ backstory, what the viewer is bringing to the show — is actually the thing that points it in either direction, whether he’s guilty or innocent, or whatever happened that night. It’s actually the viewers’ experiences that are shaping their perspective, as opposed to us telling them what to think.

Could you talk about recreating the staircase scene with Toni Collette, because it’s such a visceral sequence. It’s so gripping, but at the same time you want to turn your face away. It’s a daunting task to represent all those things all together when you think about the production.

MC: Yes, so we have the three depictions, so we visit the back staircase on that night when Kathleen passed away, three different times. Obviously, we wanted to approach it really sensitively. There were a lot of rehearsals. There were a lot of discussions between Antonio and myself about conceptually how we wanted the action to look, and then those conversations would be worked out with our stunt coordinator and stunt team and, of course, Toni.

In terms of filming it and showing it, we wanted to pay homage to documentary–style filmmaking, which is a removed perspective that’s somewhat locked down, and we wouldn’t go in for closeups or different setups or camera angles. So really, we were having to cut between two different angles, which means that you stay in the shots for longer.

Again, we did not want to put a bias on it. Whenever you make a cut, you have to make a decision, and every decision you make is actually going to be representative of something you’re feeling and thinking as a creator, as an editor, as a director, as a writer — and we wanted to avoid that. So that’s how we shot it. And I think the reason it’s beginning to feel a bit memorable is because we aren’t going in for gore and we aren’t moving close up. It’s actually the fact that we are removed and far away that is impacting people. It’s just not what they are accustomed to seeing currently in television or films.

Q: Colin Firth had a voice coach to prepare for the character. What kind of preparation did he do that stood out for you?

MC: We told all the actors this isn’t about replicating a character or a performance. Because frankly, we don’t know — we are watching these people as they are in a documentary, so to a certain extent, they are still performing, too. So we all know we don’t really know the real anyone. Like you watching me right now, you don’t know the real me. The camera creates some sort of distance. So to say that we know what someone sounds like or behaves because we’ve seen them taped — in theory, for me, a problematic equation.

But with Colin specifically, I think for him, it felt important to get some of the nuances of Michael Peterson’s voice and his mannerisms, and then of course, bring his own impression of the situation to it. And that’s a bit what all the actors did to varying degrees, which is, they wanted to embody these people but not mimic or replicate them. It feels pretty successful, because I feel what you’re sensing is not necessarily “Oh my gosh, that’s exactly what he would do”. But you’re actually just sensing more like an authenticity, or like “This feels familiar to me”. So it does feel somewhat like mimicry but it’s not that, it’s like a comfort because you’ve already been exposed to it before.

The other thing is, we didn’t want the actors to feel that way because many of our viewers haven’t seen the documentary, and don’t know who these people are. So you always want to err towards “our audience is intelligent, they know how to think”. Perhaps we want to push them in a direction to encourage more critical thinking than the typical television show.

But I think it almost feels a bit cheap to try and imitate something exactly, because then you’re being like, “You won’t recognize it if it isn’t exactly the same thing” — and that’s not the case. People sense authenticity and I think that’s what they are drawn towards.

Q: What is your personal opinion about Michael Peterson? You watched the trial on TV, you made a series based on his life. When I watch his face, it’s actually very hard to pin down who he is.

MC: Well, going to the reason this show –hopefully — feels as cohesive as it does, is that we’re writing, producing and directing a show about storytelling and one of our key characters is a storyteller. And he is somebody that likes to entertain, and has a fluid relationship with reality.

I know what it feels like when I tell a lie. I know that there’s a truth in my perspective, and that sometimes I am not fully embracing that truth.

And perhaps with our character, Michael Peterson character, the relationship with the truth is amorphous. You can’t pin it down. I think he knows when he’s lying, like about the Purple Heart — you either have one or you don’t. But I think his storytelling is “well, it’s more entertaining if I say it that way”. And that’s not a lie, that might be very true. It’s kind of like, “well I don’t have a Purple Heart, but I have these other medals, and I did serve in Vietnam, and I was exposed to violence over there.”

So to say that it’s a full lie, saying “I don’t have a Purple Heart” might be disingenuous, because “I’ve been through all the things that lead to you acquiring a Purple Heart”. So I think for us, it was really interesting to have this character who actually embodied our thesis, which is: he is the North Star of subjectivity.

He looks at a situation and puts his personal touch on it. Always. All the time.

Q: When this incident happened, it was right around the September 11 attacks, and the entire nation was in a somewhat fragile state back then. But the social climate has been changing a lot since then about gender issues, gay issues. How did you and Antonio navigate that?

MC: Yeah, I think this is a story that’s a bit in a time capsule, and it is a period piece, part of it. We weren’t going to deny that prejudice existed — and still exists; I mean, let’s be frank. I don’t honestly know how much the prosecution’s case would change in this day and age. We hope for the better, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s minimal.

What I will say is, I think the viewer might sense that these fictional conversations we created between Kathleen and Michael don’t feature some of the more contemporary discourse or lexicon that we have at our disposal today. The kind that would facilitate possibly a healthier, more well-rounded conversation regarding sexuality, regarding infidelity, regarding toxic masculinity, femininity. It almost seems like there are two people that are caught in this era where it’s like, we’re beginning to recognize the diversity within relationships, within gender, within sexuality, but we haven’t caught up yet. We don’t know how to have these conversations.

I want the conversations between Michael and Kathleen to feel like only they could have them now. But also the subtext is, these are two people that might have been actually very capable of having mature conversations if only they’d been exposed to the political discourse that we’re seeing today surrounding these issues.

So there’s almost a sense of loss in that. all of this could have been avoided had we not been carrying the burdens of prejudice. That’s totally hypothetical, but that was something that we were thinking about when we were creating this.

Q: How did the autopsy photo of Kathleen become public domain before that investigation started? It’s so unusual from a Japanese perspective.

MC: Right now, currently, autopsy photos are public domain. I’m guessing in this day and age, as we’re kind of evolving, media outlets are less apt to publish a lot of things, because we’re learning this isn’t actually what people want to see or need to see. But the reason autopsy photos are available is because it allows evidence to not be shrouded in mystery.

I think it’s a debate. I understand the withdrawal from it — it can feel disrespectful, it can feel like you’re exploiting something. But also, it’s a way that people can understand the “Look what happened”.

That being said, one of the things that we’re doing with our show is, everyone’s looking at the same photos, and those photos tell different stories to different people. But the photos aren’t changing, and it’s the opinions that are different and really, it’s what people are bringing to the photos. That’s actually how the story is told and how it’s manifesting.

Q: This series is having quite an impact on a lot of people, with family values, gender issues and other interesting ideas. What do you want audiences to take away from this show?

MC: Well, I think you just cited two very specific things. But I think our hope is even more general, which is the idea that multiple perspectives co-exist, and that there is no such thing as a single truth, and there is no such thing as objectivity. The stories that we tell ourselves, we need to be somewhat more critical of why we tell ourselves the stories that we do. I think that helps us make room for a variety of opinions. It makes room for people to live their best lives because someone isn’t judging how they choose to live.

I think you can feel one way or another about what happened that night and no one will fully know what did occur. Ultimately, okay, because there isn’t really any alternative to it. That’s the reason that I think a lot of divisiveness right now, because we are uncomfortable with the idea of ambiguity. Because it means that chaos exists, and that’s difficult when you want to believe that you have some sort of control over life. Which for the most part, you do — or you don’t. But I think just allowing people to be like, “it’s okay not to know”, “that’s the way it works”.

I understand the frustration about not knowing, but I also sense that if we move closer towards acceptance of that, that there is an opportunity for people to generally be happier.

Q: Thank you so much.

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the series.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TftAFQflBy8

I’m so excited for Emmy Contender! I can’t wait to see how it turns out.