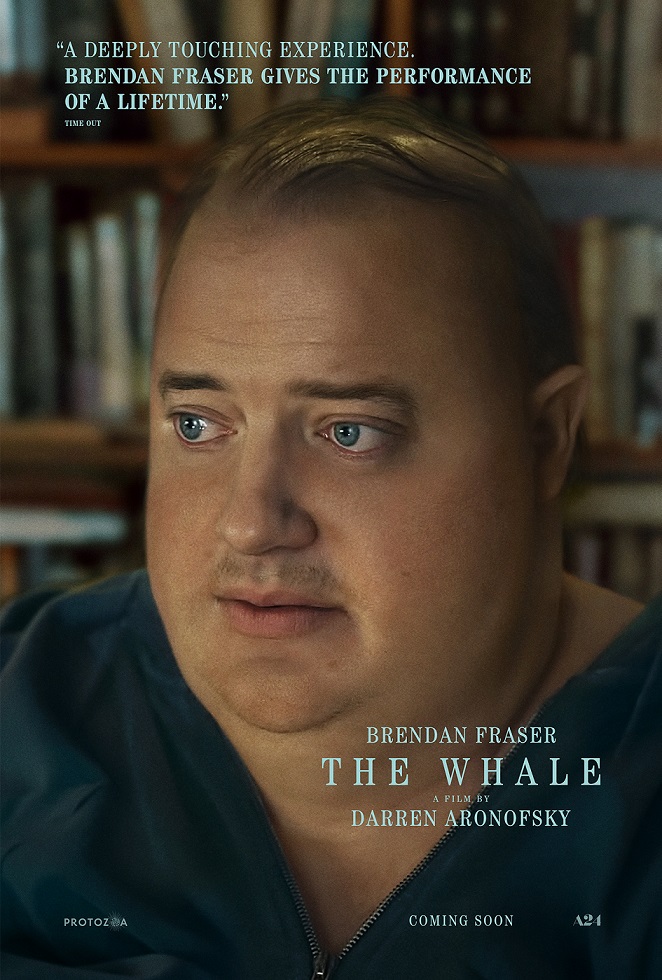

Playwright Samuel D. Hunter has an impressive resumé. He was a recipient of a 2014 MacArthur Genius Grant Fellowship, among many other awards, and he has written over a dozen plays. Among the most successful was The Whale, which also turned into the first play he rewrote as a screenplay, for a film directed by Darren Aronofsky and starring Brendan Fraser in the lead role. Hunter has already picked up a nomination from the Critics Choice Association and a number of other awards bodies for his adapted screenplay.

I had the chance to speak with Hunter about the process of turning this play into a movie, as well as the opportunity to work with Aronofsky, whose films tend to be much more far-out than this story. We also discussed how he feels about some of the controversy the film has stirred up.

Q: I’m a big fan of this film, so any chance to revisit it I really appreciate. Is this a story that you always saw as a movie?

SH: No, it’s so funny. When I wrote this play in 2009 or so, I just wanted to be an off-Broadway playwright. That was my dream. I did undergrad, grad and then did some more grad at Juilliard after that, all for playwriting. I had just fallen in love with the stage, I think mostly because it’s such a writer-driven medium, unlike film, or at least most film. I just loved that I could be at the top of the pyramid as the writer and tell the stories the way that I wanted them to be told. So when this play was done at Playwrights Horizons, which is one of my favorite theaters in New York City, that was like, my dreams are coming true. The fact that it was finding an audience and doing well, I mean, it was just incredible. It was a crazy next chapter for me when Darren called me and said, let’s talk about it becoming a film.

Q: Do you remember what your initial reaction to that was?

SH: My agent had called me, and I was walking to Washington Square Park and heading to the A train, and he told me that Darren wanted to talk about making it into a film. And I was so shocked. I just remember getting on the subway, I then lived and still live all the way up in Inwood, which is like the end of the A train, so I had this long ride from West 4th to 207th Street, where I just remember clutching my backpack and being like, whoa, what could this be? It took a really long time for this to come to fruition. I’m kind of glad it took that long, because I’ve done screenwriting in the interim. I’ve written twelve or thirteen plays since I wrote The Whale. Look, it didn’t need to take ten years, but it’s kind of nice that it did, because I think we had to figure out how to make it the right way.

Q: Were you familiar with Darren’s work before hearing from him?

SH: Yeah. I grew up in Idaho, which is where Charlie lives, and I moved to New York at eighteen to go to NYU. That was September 2000. One of the very first films that I saw was Requiem for a Dream, at the theater in Union Square. I was just blown away, I had never seen a movie like that in a theater before. I had seen some experimental films from the cult classics section in my local video store in my hometown, but it was just incredible. I bought the DVD the moment it came out and watched all the extras. I always followed his work with real interest. The Wrestler is one of my favorite films of his, if not my favorite. So yeah, I was quite familiar.

Q: It’s interesting that you mention The Wrestler. When I was speaking with Sadie Sink, I said that it feels like the closest thing to this film, because a lot of his work is incredible, but it’s so out there and just on a different plane.

This is a very intimate human story, which is terrific, but it’s not like a lot of what he does.

SH: Exactly. Yeah. And honestly, if he hadn’t made The Wrestler, look, I love his other movies, too, but they’re just not the kind of stories that I tell. If he hadn’t made The Wrestler, I think I would have been more confused. It was the first thing I thought about when he called me. I was like, oh, right, The Wrestler. He can do that, and he’s really good at that. The deeply intimate character portrait that he got with Mickey Rourke. And I think he brings the same grace and humanity to it in this film.

Q: What challenges did you find in adapting your own work for the screen?

SH: Early on, in our first meetings, I think the obvious step to take would be opening it up and adding characters, and adding flashbacks, or showing Ellie at school or Liz at the hospital, or entirely new characters beyond these five people. The more and more that I thought about that, I was like, that is not what this wants. I have other plays that probably could get opened up in that way and be successful screenplays. But the experience of this one is that you just want to be with this human being. The fundamental thing here is that you’re spending time with this very beautiful, very complicated, very multi-layered human being. Every time I ideated about leaving the apartment or flashing back, I was just like, this doesn’t feel right. But I also didn’t know if that was my playwright brain, just the lack of imagination of my playwright brain.

In one of the early meetings, Darren did say, let’s keep it in the apartment, and I was like, oh, okay, that’s I think the right choice. It’s the really difficult choice. From then, it was like, how do we find more of a cinematic language for this, while also retaining what it is fundamentally. Story-wise, it’s almost identical to the play. The event structure is almost identical.

Over the years, I slowly added things in, like, for instance, during the pandemic, I had the idea about the second bedroom, this place where he preserves that former life he had with his lover when he was happy. I added that because I had extracted this big monologue that Charlie had to Thomas’ character about his lover, and so I think with that, I found the way to visually tell that story rather than in dialogue. There are a lot of moments like that.

Q: I remember watching the film, and especially with Ellie, just noticing the presence of blocking. There’s this boundary that Charlie can’t cross in going outside, and so she also gets there and I think she realizes to some degree that she can go out and she’ll be out there and he won’t be coming with her but also that she’s being drawn back by something, which is very interesting.

SH: Yeah, exactly right.

Q: The pizza delivery guy was an addition for the film, correct?

SH: Yes. Very early on. That was actually one of the first things that I added. Funnily enough, Lincoln Center has a Performing Arts Library where they have archived videos of a lot of the major theaters in the city. They had a filmed version of the play, and right before we went into production, I pulled some strings and, even though it was closed because of COVID, I got Darren and his lead producer Ari in there. Darren was shocked to see that there was no pizza guy. He was just completely convinced, I think because it was one of my earlier ideas, that he had seen that on stage, but in fact he hadn’t.

Q: Were you involved in the casting process at all?

SH: A little bit. Darren definitely said, what do you think of Brendan Fraser? I know that he had looked at tons of different people for that role over the years, both famous and non-famous, but he had never brought a name to me before, so I knew he was really serious when he did that. I think we both knew that we couldn’t even think about going forward with the film in any way, shape, or form, until we knew we had found the right Charlie. Darren organized a reading of the screenplay at Theatre 80 St Marks down in the Village and Brendan read it. And actually Sadie was there too, when she wasn’t the mega-star that she is now. It was just so clear from the get-go, like, oh my god, Brendan is incredible. I saw a few tapes here and there for the other characters, but Darren was really taking the lead on that.

Q: I know that there has been some criticism of the fact that Brendan is not nearly as heavy as the character and that he’s not gay in real life, as well as that some people take issue with the title because they think it’s referring only to his size and not the Ahab references. How do you think about those things and reckon with them?

SH: I had the idea for the title early on, but I actually had a different title for a while because I was worried about it for that reason, but then I was like, you know what, this does want to poke at some people’s prejudices coming in to the film. It reveals that’s what you brought to it at the top of this movie. I’m just presenting a person. In terms of casting, I’ve seen so many people do this role over the years. I followed the play around in the first four incarnations, from Denver to New York to Los Angeles to Chicago. What it wants is somebody who can tell the story effectively and beautifully. And I just had so much faith in what Brendan is doing and his ability to hold deep despair and deep joy at the exact same moment. That’s what the character wants you, and that’s what the casting wants.

Q: Yes, he’s terrific. I’m curious, what was the alternate title?

SH: Oh, I’m not telling anybody that. I’m going to take that to the grave. It wasn’t a good title.

Q: Do you think it would have been more or less controversial?

SH: Way less. But it was such an anodyne, dead dog of a title.

Q: You mentioned being from Idaho before, and I remember noticing that the film is set there. Do you think that it’s an important part of this story, being set far away from big cities and the more well-known parts of America?

SH: I’ve written a lot of plays at this point, and the one thing they all have in common is that they’re set in Idaho, where I’m from. Well, I think there’s something else that the plays have in common, which is that all of them on some level are about the tragedy of isolation and the deep value of human connection. And so I think setting the plays where I came from gives me a level of insight to it. I also feel deeply connected to Idaho still. I was talking with a reporter from Spokane and they were like, oh, I went to a screening at the Kenworthy in your hometown. My grandfather was an usher at that theater in the thirties! My connection to that place runs really deep. I also think that by setting all the plays, The Whale included, geolocated next one another, allows me to focus on my larger body of work rather than one specific play. And it allows the plays to speak to one another and dovetail off one another in certain ways. I’m actually going into rehearsal on January 3rd for a revival of a play called A Bright New Boise that was produced before The Whale but I wrote it before I wrote The Whale. It’s very much a companion piece to The Whale. It’s about a guy trying to reconnect with his son, and the lens of that is that what’s blocking him is his deep Evangelical beliefs that are standing in the way of him living a normal life quote on quote.

Q: You obviously have a huge volume of work, and this also took a long time. Do you have a desire to adapt more of your own place for the screen?

SH: Yeah, I mean, I have no idea if that means adapting something I’ve written. Definitely, having gone through this process, I’m like, what about that play? What about that play?. And also, I’ve never sat down and written a screenplay on its own, so maybe there’s that. I’m kind of just on the ride of the movie right now, and I’m a little breathless at the moment, so I really haven’t had time to sit down and be like, okay, what’s on the other end of this? But I do know that this has really whet my appetite for film. Look, I had the opportunity to be on set the entire time, so I had a master class in filmmaking from Darren Aronofsky, so how can I let that experience lie dormant? So I don’t know, but the answer is yes. I just need to figure out what people will allow me to do.

Q: Well, good luck with the film, and I’m eager for people to see this film. It’s barely out so far.

SH: Yeah, six screens so far. That’s it.

Q: Thanks for taking the time to speak with me today.

SH: Yeah, of course, I really appreciate it.

Check out more of Abe Friedtanzer’s articles.

The Whale expands to theaters nationwide on Wednesday, December 21st.