Alex Pritz is a filmmaker based in New York, whose cinematic sensitivity allows him to weld humanism and ecology in a remarkable way. He worked as a cinematographer on the feature documentary The First Wave, directed by Matt Heineman, as well as on films such as Jon Kasbe’s When Lambs Become Lions, and My Dear Kyrgyzstan.

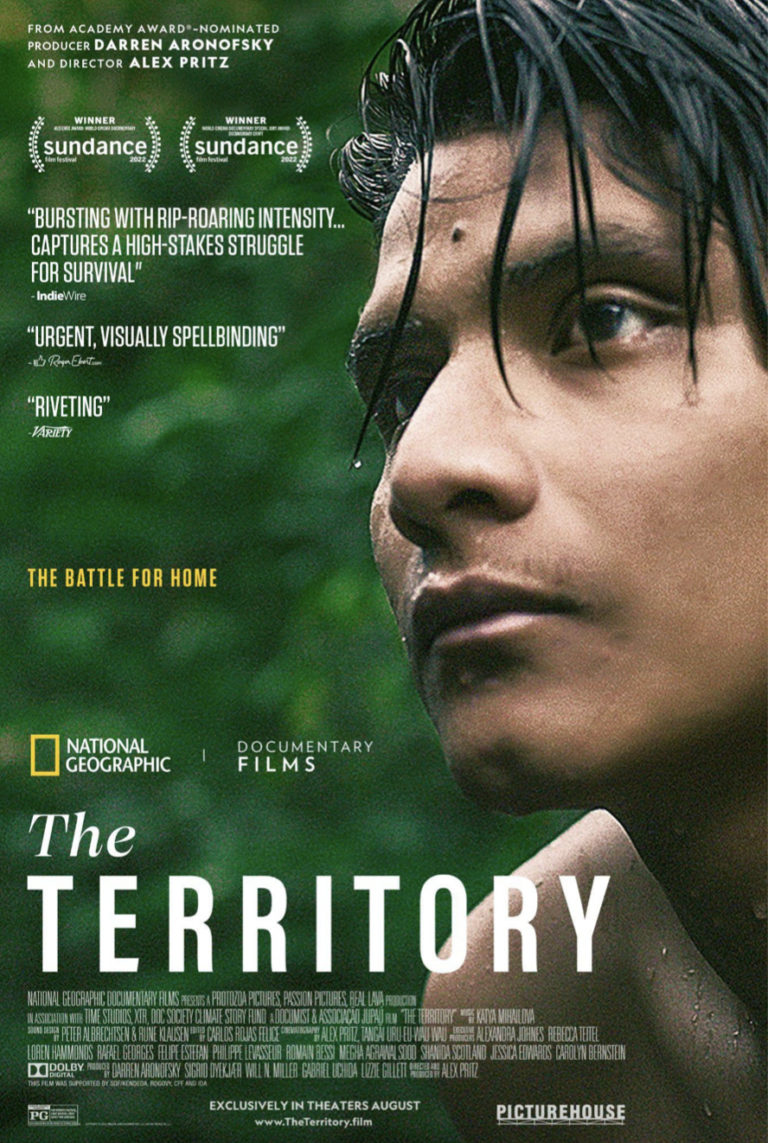

His recent work as director, The Territory, premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, where it won the Audience Awards and the World Cinema Documentary Special Jury Award. The picture, produced by Darren Aronofsky, has continued to travel around the festival circuit, gathering more accolades and is being distributed by National Geographic Documentary Films.

The film powerfully portrays the land of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau, the indigenous people of Brazil living in the state of Rondônia. The Territory is visually magnetic in the way it serves as an immersive on-the-ground look of the juxtaposition betwixt the Indigenous, the farmers and illegal settlers in the Brazilian Amazon, who have different perspectives on the way the rainforest should be managed.

In this exclusive interview, Alex Pritz shares his creative process in the making of The Territory:

Q: How important was it for you to study environmental science and philosophy to become an environmental filmmaker?

AP: For sure, my background in environmental science, philosophy, agriculture has informed the way that I want to make films. The films that I’m interested in making are about our relationship to the natural environment, but from the perspective of people who are actually living in these situations and giving it more context than the academic setting often allows for.

Q: What inspired you to go into the Amazon and bring to the screen the situation of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau people and the invasion of their territory?

AP: The Amazon is one of the most important ecosystems in the entire world — for climate change and for the people that live there, the indigenous people. When I read about the work that Neidinha Bandeira, the activist at the centre of this film, was doing, I felt really inspired and moved by her courage and bravery.

I reached out to her through email and said, “Hi. I love the work you’re doing. I’d love to meet you and talk about the possibility of making a film following your work. It looks like there’s going to be a new president [in Brazil] who could really dramatically stand in the way of some of the things that you’re trying to accomplish.”

Q: As one of your characters says, “The Amazon Rainforest is not just the heart of Brazil but of the whole world.” How important was your encounter with environmental activist Neidinha in order to make a distinctive report about this globally meaningful place?

AP: We wanted to tell a story that went deep into the lives of real people, some characters who are living through this conflict in a very personal way. It’s a local and regional conflict, but it’s emblematic of what’s happening across the Amazon. The Amazon is often called “the lungs of the earth.” It filters 20% of the planet’s oxygen and 20% of the world’s fresh water. Biologists find a new species in the Amazon rainforest every two days. So it’s a hot-bed of biodiversity, crucially important to the ecosystem.

But we didn’t want to get too bogged down in the science or the facts. We wanted the story to live by itself through the eyes of these characters. We had to find ways of getting the audience to care about these people, but also to appreciate the larger scope and the grandeur of the rainforest. That was one of the essential challenges of this film. Part of how we did that was really through sound design, the score, and by trying to immerse you in this really beautiful environment.

Q: Your documentary is exceptional by adopting a sort of “Rashomon” approach in that you presented multiple perspectives, between the indigenous people and the settlers. Without taking sides, you managed to portray them in a non-judgmental manner — how did you achieve that effect?

AP: It was important for us to show the perspective of the settlers and invading farmers because they aren’t just deciding to get up and burn the rainforest. They don’t wake up in the morning and say, “Okay, let’s go destroy this beautiful ecosystem.” They have their own internal logic as to what they’re doing. We wanted to understand this conflict in a deeper way — in a way that will allow other people to design better solutions. We had to get into that colonial mindset and understand what’s driving these people and critique them as well — not just present it, but offer it up as a competing perspective.

That came up as an idea through conversations with Neidinha who said, “Everybody comes and interview the environmentalists, but not very many people come and actually try to understand the source of this conflict.” We took that as a challenge — and ran into a lot of other difficulties. But I think empathy and compassion for other people and other perspectives is, in my mind, the bedrock of documentary filmmaking. We knew that it was something we really wanted to bring into this film.

Q: Neidinha and the Uru Eu Wau Wau people know about you filming the other side. Were they okay with you showing the other perspective?

AP: Yeah. Bitaté and Neidinha are the ones living in this really complicated conflict. For them, it’s not a simple solution or easy issue to deal with. Often I find it easier to create these black-and-white narratives, morally reductive simplifications of these conflicts while you’re sitting far away in an air-conditioned hotel in New York City or something like that. But for the people that are really there in that conflict, on the front lines day in and day out, it would be a disservice to them to not try to capture that complexity.

Q: You are both the director and cinematographer, how does the film’s visual style enhance the storytelling?

AP: We wanted to put a lot of thought and care into the images in this film. I think one of the influences, early on especially, was the Western genre — traditional American Westerns. I was trying to take some of those aesthetics to subvert the storylines or the narrative tropes that are often quite problematic. We tried to shoot with the farmers and settlers on longer lenses, making it slightly more removed, more static, and more mechanical. The really fluid, organic hand-held cinematography was used with the indigenous perspective. Then as the camera shifts, I stop filming and indigenous cinematographers took over. It added this new level of urgency and immediacy in the way that they move the camera. The things they choose to notice and frame become much more immediate and direct.

We really wanted to develop a unique visual style for this film — something that draws people in unexpected ways, to play with images, and allow people to think it’s going in one direction and then shift it and twist it somehow in the shot or the movement of the shot.

Q: Covid arrived in Brazil while you were filming, how did that affect production?

AP: We see Bitaté, this young indigenous leader, begin to use technology more and more as part of his leadership.

The technology allows him to expand their surveillance capabilities. Going out and looking for invaders with a drone becomes much more effective than going out and looking for invaders just on foot. Same with GPS, cameras, walkie-talkies — all these things really helped them expand their ability to do their work. Bitaté’s role as a leader was to bring that technology into the community.

When Covid happened, it became a natural extension to say, “Hey Bitaté, you’re already using cameras in these really innovative ways. What do you think about shooting the film yourself? Do you guys think you’re able to do this?” They were really eager and excited to take that on.

It was scary at the time — we had no idea if this would work, it felt like a really big risk. But as soon as we started getting the footage back from them, it became really obvious that this was going to be a key window into their world and give the audience a first-hand perspective of what it’s like to be an indigenous person living in this conflict.

Q: Neidinha, the environmental activist, had life-threatening experiences, including ones involving her daughter. Did you have any life-threatening experiences?

AP: Yeah. These small Brazilian frontier towns are where everybody knows everybody. So I knew that I was always being watched. I was always being analysed, scrutinised. I would get photos of myself sent to me by phone numbers I didn’t know. I didn’t know who had taken the photos, with just the back of their head or something. So there was always a fear, I think, among our team, but in a healthy way that allowed us to create strategies to protect ourselves.

When Ari [Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau] was killed that changed everything. We took security a lot more seriously going forward after that. But it’s important to say that for me, somebody who doesn’t live in Brazil, the risks that I took were nothing compared to the risks that Bitaté, Neidinha and everybody else were taking day in and day out to be able to continue doing this work protecting the rainforest. They’re the ones by far living in a much more dangerous situation.

Q: Technology is often seen as something detrimental for the natural world, but in this case we see how Bitaté and the young indigenous use technology to protect the community. How do you see the evolution of the union between ecology and technology?

AP: Of course, there’s a tension there. The technology that Bitaté is using, drones had batteries made of lithium ion that are being mined in nearby Bolivia; that’s an extractive process. So technology, in and of itself, I don’t think is an answer to any of these problems.

But it does provide a new tool for Bitaté and the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau to continue to advocate for themselves, to fight back, and resist this pressure — this quiet genocide that’s happening — in new ways. There’s hope in that. But technology itself is not the answer, it’s just a medium for them to be able to get their message out more broadly.

Q: Your work somehow evokes the Gaia hypothesis, that envisions the Earth as a synergistic and self-regulating system that interacts with all beings on the planet. James Lovelock, who conceived this concept, recently passed away. Can you share a few words on how he inspired you as a filmmaker?

AP: I loved James Lovelock and was very inspired by him. It’s a cliché to say that we’re all connected. But when it comes to the planet and these ecosystems, there’s no doubt that it’s all connected. What happens in the Amazon will affect sea level rise for people like myself living in New York City, for people in, say, Bangladesh and for people all over the world. We need to start thinking about these things more holistically, and treat the Earth as more than just a resource that we can extract from but as a living being with its own regulatory processes and ecosystem which provides services for us.

Who knows how much of a cost in dollars it is to filter 20% of the Earth’s oxygen? That’s something the Amazon rainforest is doing.

All the money in the world, all the effort we’ve been doing right now, couldn’t do that. Simply, in financial terms, we need to do that. But also from a spiritual sense, it’s important that we begin to treat the Earth with respect and gratitude.

Q: Indigenous affairs agents said they can’t fight with the invaders. They also said Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau people made up the story, and want proof. Why didn’t the agents just go there to find proof? The organisation that was supposed to help the indigenous people didn’t help them.

AP: There’s a real vacuum of power in this government. That phone call happened just a few days after Bolsonaro took office. You began to see the effect of this new administration quickly in terms of cutting funding for these organisations, pulling people out, people lost their jobs.

The good people working these organisations, a lot of them had to leave their jobs.

It had a chilling effect on the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau and Neidinha and their ability to do their work. But we also see them begin to take on that responsibility themselves for protecting the rainforest and fending for themselves in defending their lives.

It’s one of the things that I hope whatever administration is coming next in Brazil will prioritise: funding and enforcing these environmental laws that exist on the books.

Q: This film won both the Jury Prize and the Audience Prize at the Sundance Film Festival. How much does this help you go to other countries to make the world aware of this crisis?

AP: Being at the Sundance Festival, being accepted there, and any awards that have come since, have helped broaden the audience for this film in a really important way. It’s helped us reach new people. It’s helped us get this message out in a much stronger way.

All of the wonderful recognition the film has been getting is really, really heartening and encouraging for everybody that’s engaged in this work and for the filmmaking team to be recognised for their cinematic craft. There’s a lot of emphasis on the messages of the film, which are wonderful. But there’s also a lot of people who spent a lot of time thinking about the cinematography, the colour, the sound design, the score, so to have their work acknowledged as well is really meaningful for me.

Q: Nowadays, young people around the world have taken the climate crisis to heart, as they prompt governments to take action. In what way do you think the film industry can act as an accelerant to affect policy decision-making for a more sustainable future?

AP: There are certainly policy goals that we have in terms of reducing deforestation-related supply chains, or in helping fund indigenous surveillance and monitoring work. These are concrete things that our team and our impact campaign are focused on. But I think more broadly, the message that we want audiences to leave with is that indigenous people are the best conservationists on earth. They preserve 80% of global biodiversity — it’s bound within their land. Any conversations about climate change need to centre on indigenous voices as the authors and the sources of wisdom as we think about a blueprint for our collective future where the Earth remains a beautiful and habitable place.

Q: For the characters of “The Territory” who have seen the finished film, what was their response?

AP: Their response has been wonderful. We showed the film to all of the Uru-Eu-Wau-Wau community. We showed scenes, rough cuts, and the final thing. We had a premiere in Brazil. We were at the It’s All True/ É Tudo Verdade Film Festival in São Paulo a few months ago, and a third of the audience, maybe half, was indigenous. A really beautiful reception. As for audiences here in New York, we’re opening this weekend and it’s been a really, really beautiful welcome.

Check out more of Chiara’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.