Q: How did you start the project for this one? What’s your relation to Mars?

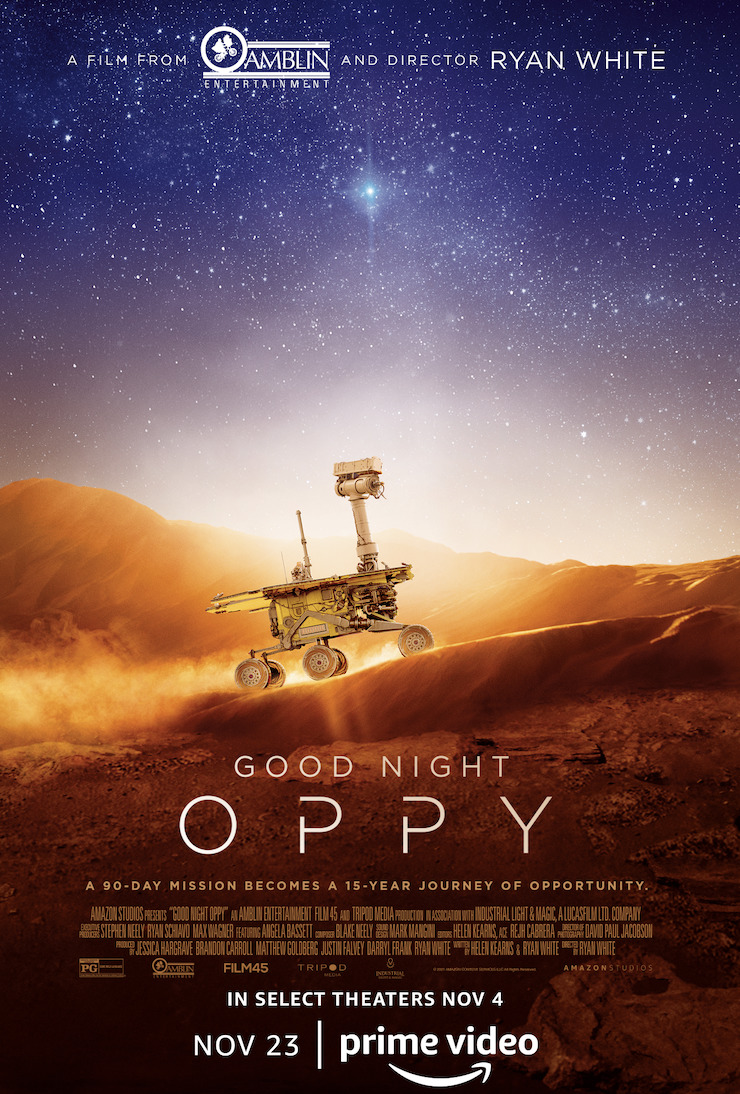

RW: I’ve always been a huge space geek. Growing up, I always wanted to be an astronaut and I followed all of NASA’s missions. Some of my favorite films were space films — “E.T.” is still my favorite film and it was my favorite as a little boy. When I became a documentary filmmaker, I always wanted to find a story that took place in space, and just never found the right one. Then a few years ago, the year after Opportunity had died, this opportunity was brought to me by Film 45 — Pete Burke’s company — and Amblin, which is Stephen Spielberg’s company. They had gotten access to almost a thousand hours of footage from NASA, and NASA was giving the film their blessing. They were looking for a director, and I knew right away it was finally the space story I wanted to tell.

Q: Right after the moon landing in 1969, NASA sent two orbiters and two landers to Mars. Principal scientist Steve Squyres wrote the original proposal for Mars exploration, which failed in 1980. But the idea of exploring the planet started a long time ago, so was it surprising to you?

RW: It did surprise me. As children, we grow up and Mars is like the little red planet. It’s where most science fiction takes place. Martians have always been these creatures from storytelling and folklore. But I don’t think I understood until I started making this film, how remarkably similar Mars is to Earth. It is our sister planet, and, relatively speaking, it’s quite close to us. The intent from the beginning was, once we had satellites that could look down on Mars, to send a scientific expedition there to find out the history of the Martian terrain and atmosphere. That’s been the goal since the ’60s — to try and find those answers. Of course, Opportunity and Spirit were a big part of finally solving that mystery.

Q: The world learned about the exploration of Mars when the two robots sent back data, but most people probably didn’t know how long those robots lasted there on the surface. How did those robots stay and explore Mars for such a long time? It was not intended because initially their expected lifespan was only 90 days.

RW: Well, 90 days was the expectation but that was also a conservative estimate. NASA always wants to meet those mission requirements. But they had the idea that they could last longer than 90 sols. But 90 sols was the minimum that they wanted. It was a couple of things. First of all, yes, the dust devils, appeared at the beginning to be like they could be dangerous, an enemy to the rovers. In fact, it ended up being the opposite: they were their best friends. Also, they built these rovers in a really reliable way. They were built for Mars, not for Earth. I’ve heard many people say they didn’t operate that well on Earth, so we just had to trust that, once they made it to Mars, that was the terrain we developed them for and they would work better. So really, it came down to genius engineering that these rovers, and the hardware in them, stayed intact for so long. It’s quite the engineering feat, and it proved that they were built perfectly for Mars.

There are two rovers currently on Mars — living rovers, I should say, Curiosity and Perseverance — and they’re much more technically savvy. They’re much bigger, their wheels are more durable, and they aren’t solar-powered anymore. They have nuclear batteries, so their life doesn’t depend on the sun and dust anymore. But yeah, it was those phenomena — mainly the dust devils — that extended their lifetimes.

Q: The Mission Control team made musical choices that were played at crucial points during the mission, such as “Born to be Wild”which was heard in the morning. When one of the rovers, Spirit, didn’t call home, they selected ABBA’s “SOS” to be played. They had great ideas for their music.

RW: Yeah. One of the best surprises in making the film, were finding these wake-up songs, which shows that it comes from the tradition of doing that for astronauts on missions.

Q: Even before the Mars mission?

RW: Right. Human beings being the astronauts were woken up with a wake-up song by NASA. They extended that tradition in a kind of cutesy way to the robots’ mission as well. It also helped build morale, like a morning kickoff to jolt some energy into the group because they were all living on Mars time. They often worked in the middle of the night. Everyone thought the mission would only last 90 days so that would be two rovers, 90 days, 180 songs. But no one thought that the robots were going to survive for years so it ended up being thousands of songs that were picked over the years. There’s a Spotify play list of the songs, both for Spirit and Opportunity. Some of the best moments in making this film were when someone was logging footage — people on my team watched every minute of the archival material and took notes on it — and when they found a wakeup song among the footage [it provided] some of the best moments. My favorite, of course, was ABBA’s “SOS” because it was such a sad time for them, but you see the energy changing in the room as the chorus hits. It definitely gave our film a lot more entertainment value to be able to include those songs.

Q: The rovers were deliberately created to have human characteristics. Robot cameras have a human’s 20/20 vision; their height was 5 foot 2 inches. Can you talk about the creation of the rovers?

RW: A lot of it is function over form, right? So yes, the rover needed two eyes and the people working back on Earth needed to be able to have depth perception when they were looking at the photographs to chart out the path. A lot of the reason the rovers had human characteristics is because they were an extension of ourselves. They were going to a place that we couldn’t go ourselves. We were sending them there as brave explorers to do the work we wished we could do. If a human being could go, they would need eyes, an arm to do all of these measurements, and would need wheels or feet to move around. A lot of those are essential to make the robot into a geologist, and a geologist needs them. I think the less literal answer to this question is [that] NASA deliberately created a cute robot. They could have created something that wasn’t adorable. And these robots [were active] a few years before WallE came out, which they are always careful to remind us. But there was something about these cute robots that they knew the public would want to come along for the journey. The whole point of NASA and all these incredible missions is that they do discovery. They want the public — who are the taxpayers — to be a part of it. In designing this adorable creatures, it invited in a very broad audience who wanted to go on the adventure with them. So I think it was a kind of genius in foresight.

Q: Vandi Verma, the operator who drove the rovers, was pregnant with twins, and had her own way to relate to them as if they had personalities. All of the staff had their own attachment to them. Can you talk about that personal attachment?

RW: It’s their pride and joy that they’ve poured all of themselves into this project. Even the idea that the rovers could land safely on Mars was very unpredictable. You go through this incredibly stressful launch, then through the stressful journey to Mars which takes six and a half months. Then you go through, perhaps, the most stressful event — the landing of these rovers, which is life and death. Suddenly your rovers have made it there and are safe. They’re beginning their journey, and you think it’s a countdown of 90 days that they’ll be able to live through.

But as they kept surviving — one year, two years, three — this emotional attachment grew even more as time passed. You start thinking, “Maybe we have forever with these rovers. The dust devils keep saving their lives.”

I’ve heard many times, that the emotional attachment grew as the rovers got older. Of course, people go through their own life events like Vandi Verma. She had her own twins, and own unique take on how she related to the twin rovers. There were deaths, and births, so other people had begun to see the rovers as a part of their lives like family members. Even though they’re inanimate objects, people couldn’t help but form feelings for them.

Q: How did you choose Angela Bassett for the narration? Her tone of voice fits very well for this film.

RW: She was always the voice I had in my head when I was writing this film. I didn’t write these words. They’re not narration, they’re the words that NASA wrote in its daily Rover diaries. It was a great device that I had access to because it’s written in present tense, like in the moment. That’s rare. When you interview people, they speak in past tense because they’re looking back on this experience. But we had this daily diary and wanted to bring it to life. I wanted an actor to do it. I always had Angela’s voice in my head. She’s playing the voice of NASA so you need someone who sounds incredibly wise — like the mother ship. I also wanted something very maternal because the feeling these people had for the rovers was often described as a parent-child relationship. I feel like Angela’s voice has that protectiveness that I wanted.

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.