©Courtesy of Japan Cuts

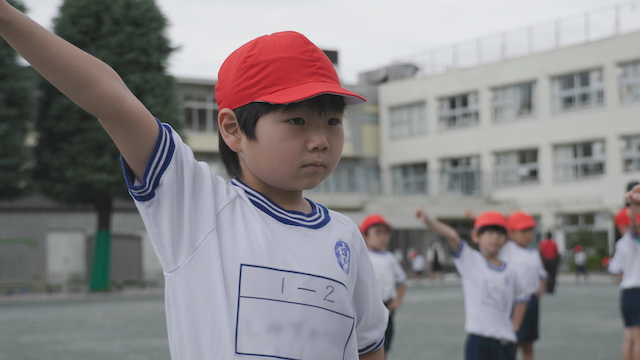

The Making of a Japanese : Located in one of Tokyo’s sprawling suburbs, Tsukado is one of the largest public elementary schools in Japan with nearly 1,000 students. In the nation’s unique educational system, children are tasked to run their own school in order to teach communal values and how to play one’s role in the group. Intimately capturing one school year from the perspective of 1st and 6th graders, THE MAKING OF A JAPANESE has the magic of childhood with precious moments of joy, tears, and discovery — as they learn the traits necessary to become part of Japanese society.

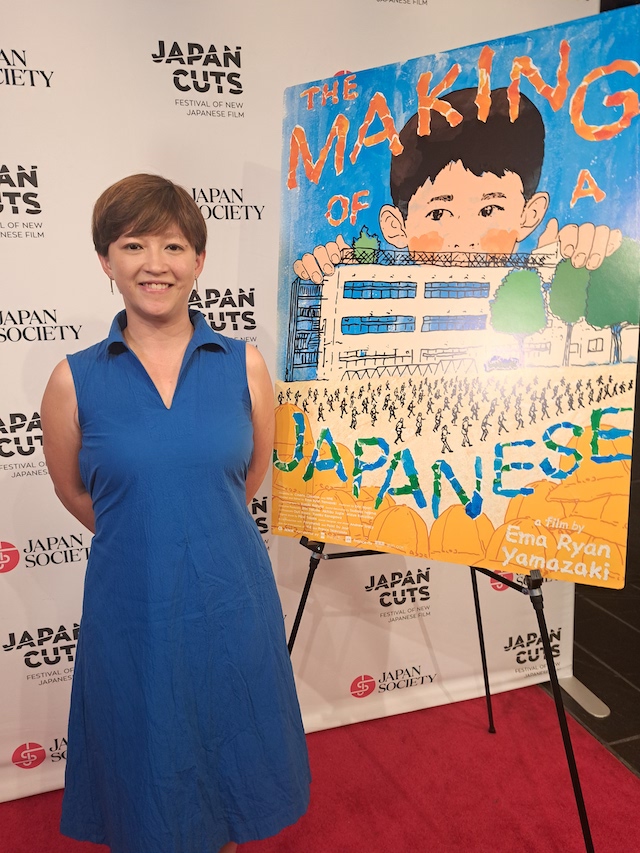

Directed and Edited by Ema Ryan Yamazaki (Documentary Feature / 99 min)

Tokyo International Film Festival ‘23 / Thessaloniki International Documentary Festival ‘24

Co-Production by Cineric Creative + NHK + Pystymestä + Point Du Jour / Participation of YLE and France Télévisions, World Sales Autlook Filmsales

Exclusive Interview with Director/Editor Ema Ryan Yamazaki

Q: You had your own kid a few years ago, did that propel you to study and research Japanese elementary school? How did you get started? What was the motivation behind making this film?

Ema Ryan Yamazaki: My son just turned two. But it’s taken 10 years to get this film out from when I had the idea. The film came first by a long way. I see. It’s somewhat by chance, but also it was our wish. I was pregnant during the shooting of the film.

I gave birth about six weeks after I finished shooting. I continued to edit the film as my son was a newborn and in the first year of his life. As a result, I feel like I have always said that I think the Japanese elementary school system is really interesting. If I had a kid I would put them in Japanese elementary school, just as I went to Japanese elementary school.

But it became a reality. I still believe that even after making this film and seeing the behind-the-scenes, the reason I wanted to make this film was that I was interested in explaining why Japanese society is the way it is. I think a key answer, why Japan is the way it is, is because of our elementary school system.

I grew up in Osaka and went to a Japanese public elementary school. As I look back, I realize that everything I learned about my Japanese-ness I learned in these six years of elementary school. I went to an American school for middle school and then came to New York. [My education] became less and less mainstream Japanese.

My idea was if I examine the incoming first graders who are six years old and don’t know anything about anything yet, we filmed them learning how to be part of the school system. We also filmed the sixth graders who are six years later and see how they’ve become leaders in their school.

We can learn a lot about why Japan is the way it is. I think we’re the only school system where we clean our own classrooms. Everyone has a responsibility and role. it’s not a burden. We want to do it. It becomes normal to be given duties and responsibilities. There’s a community — that’s built [that way]. Of course, sometimes, the group mentality is too much. It’s not all black or white, but I wanted to highlight the uniqueness of it and present it to the world.

Q: That was a great comparison. You decide to pick students from first grade and sixth grade, even though there’s only a five year difference. Kids can learn a lot and teach something to a younger generation.

Ema Ryan Yamazaki: It’s clear to me that something happened in those six years. I feel that five year olds, anywhere in the world, are kind of similar whether in New York, in Japan or in Europe, wherever. But by the time you’re 12, a Japanese 12 year old is quite different from a 12 year old that we see in New York. I wanted to document what especially happened in that first and last year. Sometimes I was like, “Should I film for six years with the same kids?? But it wasn’t realistic. it’s a symbol of what in first grade, the characters of the sixth grade experience.

Now look at them. By filmmaking it’s a very useful tool. I’ve done it in my other films too, where you document the new people of the environment, whether it’s the first graders or for my baseball film. I do something similar with the freshman students coming in. It’s a useful way to teach the audience as they experience things just as the characters are experiencing them. I found it to be very useful.

Q: I thought teacher Endo was very engaging. He’s a very old-school type of teacher that scolds students very loudly, but teaches you good lessons, which sometimes raise the eyebrow for other teachers. Those teachers are very passionate and are the ones that we like and try to get good grades from them.

Ema Ryan Yamazaki: First of all, I think it’s so hard to be a teacher, especially nowadays just being at this school for a year and seeing everything, in japan, the teachers are overworked. The parents are demanding they have to teach a curriculum? The kids have all sorts of childhood problems. These people are supposed to raise the next generation.

It’s a really difficult job. I have a lot of respect and empathy for the profession. I made the school itself the main character, so I could show not one teacher or one student to represent the system, but to actually show it as a whole. there’s more traditional, stricter teachers, but there are teachers who take the position of being close to a friend to kids which is more of a new way I think.

When I was growing up 30 years ago, all my teachers were very strict. I didn’t expect my teachers to be friends. So I also observed changes, Each school, each grade has different classes, different teachers. As a whole, it felt like it was really well balanced. How strict should we be with our kids? There was a Showa period when it was way more strict. I’m of the early Heisei generation where it was still quite strict. For me, teachers like Endo really shaped me to be who I am. Teachers pushed me. I faced challenges. I overcame it.

The boy with the skipping rope or even the little girl that’s pushed and then cries, they overcome those experiences and that really formed who I am as well. I understand also, depending on what you’re used to, that some people think it’s too much. but I think Japan is the way it is because of that type of education.

I think we should talk about how much of that we should continue — what are the pluses and minuses. Japan is also a society where things are just orderly. We’re known for hard work so it’s all hand in hand. it’s all connected. I want people to think about it. For me personally, I think it’s easier to not be strict like teachers who don’t want to be but I think teachers are taking on an extra role they sometimes have to play.

Educate our kids. It’s more than being supportive. You have to be there, but you have to teach. And I think I wanted to highlight some of that, but also the struggles of that, especially nowadays, when I think there’s more pressure for people to, like strictness is sometimes an issue.

©Courtesy of Japan Cuts

Q: When one of the kids, Kato-kun, didn’t want to choose s school activity due to the fact that there’s nothing he was interested in, but the girl Yanagawa-san suggested he switch the activity, I thought that was a great lesson.

Ema Ryan Yamazaki: We were there for 150 days out of one school year and we filmed about 700 hours, but I was there for thousands more when we weren’t filming. I was always trying to be there when things like that happen. I’m not just seeing it, but capturing it. The best of what I captured is in the film but a lot of things happened. You have to have the right view at the right time, get the good shots, have good audio. So this is what’s really challenging about making this kind of film.

what you mentioned happened a few times where the kids were kind to other kids. I’m not saying it’s only in Japan, but I think it’s particularly amazing that at such a young age there’s this kind of, not just friendship, but it’s like the feeling of “we’re in it together and so we support each other.” We sometimes help each other more than what you think. You offer it to the other person, or you make sure even a young boy, when his classmate, Ayame chan, is crying he goes over to see, and he’s six years old. He’s trying to make her feel better, but be like, I messed up too. Let’s try, it’s just these words that you can’t write. If people were writing a script about children, you wouldn’t expect them to behave this way.

Again, I think it’s part of the Japanese community’s collectiveness. I know that these days, words like shudan or group, especially in Japan are viewed almost a bit negatively. We want to be more individualistic. I think that balance is really important, but I also wanted to highlight the things that are so common in Japan and with kids because that’s where this kind of education is.

You’re taught to be part of this class, this group. you’re responsible to your group. It’s not just about you being okay. That’s maybe more like a capitalist, sometimes American, system of fighting for yourself to be at the top. I wanted to highlight these things because I do think it’s uniquely Japanese — for better and for worse.

Q: During COVID, they had a shield to protect from getting the disease, not just wearing the mask.

Ema Ryan Yamazaki: You have this shield during lunch, so you can’t talk when you have your mask off. So lunch is totally silent. And you have to have masks on at all times, except when you’re eating or drinking. If you’re doing sports or something, you have to keep your distance.There’s a very strict two meters, the six feet rule. This was so interesting. I read a lot about how in the U S there was a lot of trouble with that, especially in forcing kids to do it. Of course, we’ll see in the next five to 10 to 20 years, the impact of COVID in the long term.

How many people died? A lot of kids in the U. S. weren’t able to be at school. There was a lot of online learning, and in Japan, it was just the first three months. After that, schools never closed and it was asking for extreme sacrifice from the kids, like not talking while you eat, or not holding hands with your friends, but education kept on going. I think, again, different people can say which was better, but I was amazed with the creativity within the restrictions and a determination to keep everybody safe. They kept going In a way that I think is not only in Japan.

It was these traits of Japanese society that happened that was one of the reasons I planned to make the film. In April 2020, we were ready to film and then COVID happened. I had the choice of either filming the following year or just giving up and waiting until life was back to normal.

The reason I decided to make the film during COVID, even though it was not part of my original idea, was that I was interested these character traits, in how people function which were further emphasized [during the pandemic]. It came out more in a weird way during COVID. I thought it was a great opportunity to capture that unique time. Every culture, I think, revealed its kind of true colors during COVID. I think I captured that for Japan in the film.

Q: During the lecture of professor Hiroshi Sugita, he addressed that In Japan. Besides the classroom, teachers have to teach students that social life is also a subject of education in a way, things such as a school lunch menu, cleaning up and so on. Do you think Japanese teachers have a lot of tasks?

Ema Ryan Yamazaki: it’s clear that teachers, especially elementary school teachers do. Of course, you have to teach the basics math, science, social life, but it’s a holistic human education. it’s almost as important to learn these kinds of values and skills as people living in the small society that a first grade class or second grade class is. their tasks I think are so much more than I think what a teacher in the US is expected to do.

That’s tough because that’s what makes the Japanese school system amazing and unique in a way. So much of the burden is on the teacher. there’s now measures to try to shorten the hours, but some teachers feel that what’s being cut is what they enjoy the most, which is being with the kids more.It’s hard for them, I think, since they approach it as a holistic job.

But for sure, I think it’s so hard to be a teacher. Now that I’m a new parent I understand parents’ feelings too, but the parents’ demands feel almost unrealistic. They expect the school and teachers to do so much. Schools in Japan and elsewhere are so closed off. Sometimes it’s about not knowing what is going on with the school. I hope that by just showing what it’s like to be in a school people will have more empathy for people who are just trying to do their best.

I know sometimes it’s frustrating if your own child is going through something, but I think it’s important to open up that world so people can see it. Sometimes I think parents just don’t know what’s going on. schools should be more open if they can. That’s what I thought.

©Courtesy of Japan Cuts

Q: That’s true. Professor Sugita addressed the way of collective responsibility in Japan. Japan’s high level of collectivity is one of the things the world wants to imitate but it’s also a double-edged sword which creates bullying.

Ema Ryan Yamazaki: It’s a double-edged sword. I feel this way about so much about Japan. Everything that makes Japan great is also what makes it a tough place to live. It’s hard because the way things are is what tourists and people admire about Japan. we’re unique, but those are the same things that can tip towards the negative.

In elementary school, there are a lot more positives when you’re younger. you learn how to be responsible for something that’s bigger than yourself. But as you get older, as a teenager its different. Then as young adults it’s all about how you fit into the group or how you dedicate yourself to the group. if you don’t fit in or your individuality, uniqueness, is affected and as a result, you don’t feel like you fit in.

Sometimes you get bullied or like the professor mentions, the suicide rates and these problems are all coming out of the same system. there is no perfect system, but I go back and forth between. Tokyo and New York often, and I think somewhere in the middle of this Japanese system and the amazing system of the U.S., which is so much about creativity and freedom and individuality, but maybe not as much about considering others I think, is maybe the perfect way that no place has, but it’s again a way to think about These things. And cause I think, especially in Japan, there’s a lot of self criticism.

No matter what tourists say about Japan, people in Japan don’t really appreciate the basic things of Japanese society because it’s so normal, I was the same way when I was living it took me to New York to Oh, trains don’t run on time everywhere in the world, or streets are not clean automatically because New York was dirty and the trains were unreliable.

But when people don’t have that perspective, it’s a lot of criticism, which I think we need to criticize and help encourage change, but it’s not all bad. Some of the school system is amazing and I wanted to also highlight it so that people, teachers and people in education can feel confident about those things.

And then obviously identify the issues that we also have instead of just being all bad. I’m curious to know, during the COVID, obviously the students can go to the actual school trip. And I’m curious to know what kind of things the teacher offers?

Q During covid, obviously you can go on a school trip, so what kind of activity that teacher had to offer, in order to engage in something in school?

Ema Ryan Yamazaki: I feel because of the restrictions of COVID, of course. Sometimes things couldn’t happen with all these rules, but I was so amazed about the creativity that the teachers came up with Even the kids are trying to. sometimes different grades were not allowed to mingle in case they spread COVID. they would do video chats online, like within schools, just to be able to talk eventually school trips were allowed.

As you mentioned earlier, it’s a big part of the Japanese school system, that grade six. mentors grade one there was an issue of them going together and holding hands? They wore gloves so they could hold hands with each other. It was safe, but they had that experience. It’s extreme to have to wear gloves to hold a hand.

But if that’s what it took to carry that spirit, I think that was very creative and much better than not doing it. So many things didn’t happen and people gave up the times I saw, people trying to figure out a way to do it. I think some of that is going to help now when we realize, so what do we want or don’t want now that COVID is gone? some of those lessons could be carried over. So that’s the things that I enjoyed observing.

Q: What’s engaging about this, during the sports day, is that you don’t need to succeed as a student running or throwing some ball or whatever. What’s amazing is trying to challenge obstacles in a school activity or any kind of sport. That was the way to teach. People often compare themselves with other kids, but at the same time what is important is just coping with the obstacles on a daily basis.

Ema Ryan Yamazaki: Now that i’m in my mid 30s, what I most remember about my elementary school days is sports day and it was so hard. you were given what felt like an impossible task to perform whatever with your classmates and you know in the film you see this one boy Going from being a really bad skipping rope person to becoming really good at it. And those are the type of challenges.

I think it shaped me like I learned how satisfying it feels to work hard and get better at things and also that a little bit of pressure makes it easier to work hard when everybody else is also trying because I’m not such a strong person. but the idea of like, when everybody else is also trying, and I learned that feeling when I was 11, 12 years old, and I think again, at least up until now, a lot of Japanese people and Japanese society is built upon this kind of spirit. People say konjo (effort).

This konjo is now old, but I think that spirit in moderation is really a foundation of how we are. And I think sports day in the U S it’s like a one day activity in Japan. It’s like you practice for four to six weeks before, but the key thing is. Also, Japan is changing, and there’s a lot of talk about not doing as many of these school activities, again, to lower the burden for teachers, But I personally hope that as you witness in my film this is what makes the system unique.

Ultimately I understand math and science and like academics are important, but at that age, I think these kinds of memories and what you learn, can form the basis of who you are. So I just hope that we can figure out a way that Japanese education can recognize the value of that and do it in a way that is less burdensome for the teachers, but still has that magic that I remember receiving from the system.

©Courtesy of Japan Cuts

Q: You have a really great title, Making of Japanese. How do you come up with that? I think that was really great because when you think about forming age from first grade to sixth grade, so how do you come up with that title?

Ema Ryan Yamazaki: I just think, and I know it’s a little bit like. Startling especially in Japan and the Japanese title is not quite the same because I want that film to have a chance to be seen. I don’t want to offend people just for the title. I stand by that.

It’s a great title too because first of all two things like I think I get to title it because My father is British and I grew up in Japan and I’ve always been labeled half my whole life. People have questioned my Japaneseness. I’m in this situation where I have to constantly prove or think about what it means to be Japanese.

One of the answers that I’ve really come up with for myself is that I feel Japanese and am Japanese. Not just because. I grew up there and I speak Japanese and have a passport and all these other criteria that people say, but I went to Japanese elementary school and I feel like anyone who goes to a Japanese elementary school has that essence. Even if you, maybe in the future they’ll, there is now more.

Kids who come to know their parents are not Japanese or I just think that was my kind of funny but real like answer to this question and I think and I understand I’m playing on this idea of Japan being this one homogeneous place and it isn’t but it is way much that compared to a place like America or New York, and I’ve been the kind of Victim and of that being a little bit different but also like seeing the benefits of it.

I just wanted a title that made the film seem like it’s not it’s of course about individual students and teachers year and their growth and their ups and downs and It’s people say it’s cute and I get it and I love that because I wanted to show the magic of childhood but ultimately what i’m trying to get people to think about is How this reflects on society and that I think the title does that the Japanese title is which essentially, again, it’s that same idea.

It’s one of the titles that got people to think it’s about a school and about these kids. I wanted to reflect on how this is like feeding into our society, so this is why, yeah, and I had the idea of the title like many years ago and it never changed basically, yeah, okay, so this will be the last question. This film was selected at Japan Cuts. How do you want the audience to take away from this film? You talked about briefly in the past, but Yeah, for sure. I think I’ve been fortunate enough to screen this film in many countries this year.

I have two wishes. One is of course, I do think the Japanese school system has something to offer. I wanted people to learn about it, see about it, maybe they don’t agree with everything they see, but I think already some reactions from people is just “Wow it’s different from us.” A lot of people speak about how impressive it is.

The children are at a young age and there are things that they don’t see in their own society. I wanted to present and tell stories that are not just about sushi and anime, ninja, and these things that Japan is known for. If people are interested in Japan, it might not be that simple, your first idea might not be what it is. I think this is what makes my work unique.

Once you do watch it, I think you will learn a lot more about Japan. Again, it’s a mirror into the education system of your own city or country today. In New York or in Finland, this film has been playing for three months in theaters and it’s been about what we think about our own schools versus what we saw on screen.

It inspires conversation. I love it. We all think Finland is known for its education, but apparently within Finland, there’s a feeling that the education system has lost a sense of community that they used to have. They’ve really turned to this film to use it to think and talk about that. Whatever that is for each country, whether they take what they like and don’t like about what they see. I wanted to reflect on and get people thinking about education because I think it’s the most important topic of a society.

Yet often it’s not in Japan. Definitely it seems like it should be, that people should care more about what kids are learning. It’s hard sometimes to get that conversation going and more than “Oh the teachers are overworked.” I just want education to have more of a role in the conversation in society. Those are my hopes for this film.

©Courtesy of Japan Cuts

If you like the interview, share your thoughts below!

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.