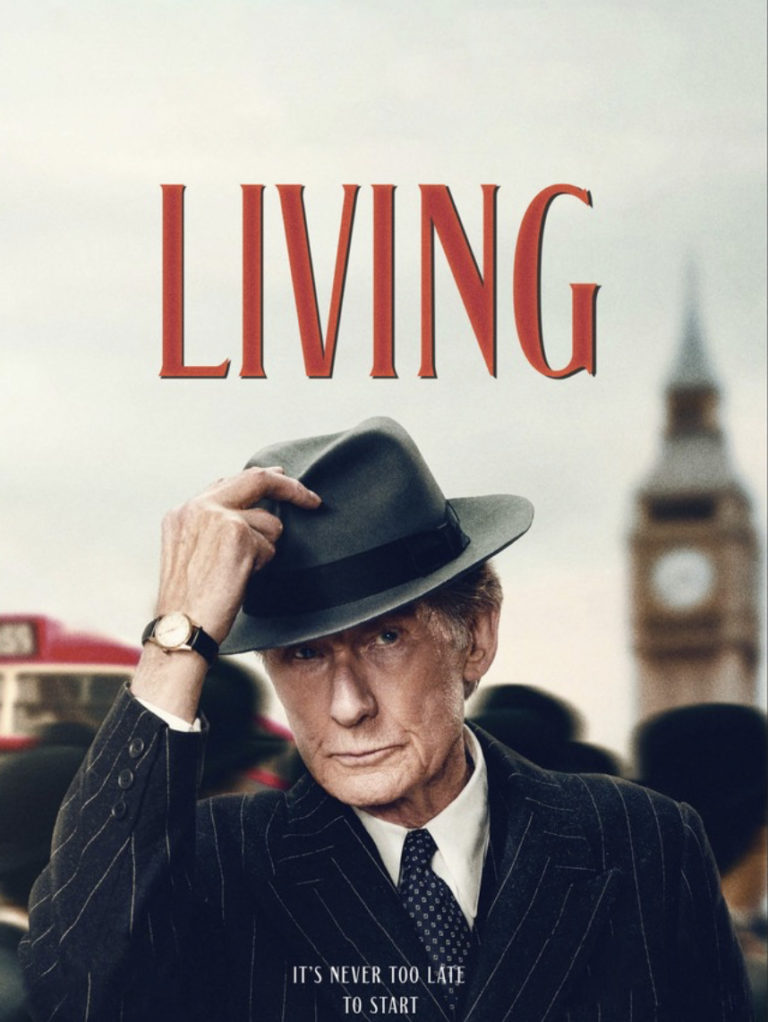

Photo by Npt - © Andrew Testa

Q: The original Akira Kurosawa’s film, “Ikiru” had such impact on your life. What kind of element stood out for you that made you decide to tackle the screenplay?

KI: I think all the things that struck me the first time I saw this — and I think I must have been very young. I think I was about eleven or twelve, something like that. I think there are still the things that I find most important about the film. Because often you see a film when you’re young and then you see it again many years later, it feels like a different movie and you think, “Why did I think this?”

“Ikiru” is an interesting case because I almost “got” it as a child. I think what was important to me was, yes I was an English boy growing up in England with very little contact with Japanese culture. I was going to school every day on the train — I had something like a twenty-minute train journey — to my school. I would travel every morning with these English commuters who had bowler hats and umbrellas, and they were on their way into London. (My school was closer.)

When I saw “Ikiru”, I made an equation with the Japanese bureaucrats I saw there, and these kinds of English — in those days you considered them “English gentlemen” — they were trying to be English gentlemen — going in to work on the commuter line. I suppose I thought when I finished my schooling, the natural thing was that I would go from being a boy in a school uniform to one of these people. There was a kind of — both sides, the English side and the Japanese side made quite an impact on me, although it was about a much older person. I somehow thought this would say something about the life I would have.

And what I found very inspirational was that it suggested that, even if you don’t become some kind of “star” or do something fantastic or become very rich, it doesn’t matter. You can be somebody quite humble, like Watanabe-san in “Ikiru”, or Mr Williams in our film. You can still make an effort — you have to still make an effort. If you make an effort, then your life could actually become full. So that was an upright position for me as a young person. I never dreamt that I’d be allowed to do the things I’ve been allowed to do. I thought I would have a life rather like Mr Williams.

Q: When they announced the remaking of “Ikiru”, some of the bureaucratic elements and politeness could transition to the English setting. Is this something that you cherished from the original film that you wanted to adapt into this film?

KI: Yes, I think you’re right that there’s a certain Japanese manner that you see in “Ikiru” which transfers quite naturally into the kind of manners that English people liked to display at that time in England. As I was growing up in England, those kinds of manners started to change quite rapidly, so that by the time I was a university student, they were deeply unfashionable. But certainly for the generation the same age as my parents, the English people of my parents’ generation, they thought that was the correct way to behave, even under great pressure. And it wasn’t just manners, but it was even the way of putting people down, or influencing your position in society. It should be done in a certain kind of way. I think there were, perhaps, parallels between Japan and England.

But I would say that there was an important difference, for me. In “Ikiru”, [Akira] Kurosawa and his writers, Shinobu Hashimoto and Hideo Oguni, wrote their movie in 1949, 1950 — some time like this. [The movie was released in 1952.] At that point, they are right to be quite pessimistic about what this bureaucracy, what ordinary bureaucrats like that can achieve. Japan has gone through this terrible section of its history — this militaristic rule, this terrible war, the atomic bombs, American occupation. Kurosawa and his team had no idea that Japan would become so prosperous in a few years’ time. And not only that, [that] Japan would become this very solid, liberal democracy. They had no idea. So I think Kurosawa’s film is quite pessimistic. It seems to me that there’s a feeling that, never mind the little spark that you see from Watanabe, it will all be crushed by the weight of bureaucracy and just the huge burden of trying to rebuild Japan.

For us today, we have the benefit of hindsight and we know that Japan rebuilt magnificently. And I feel that Britain also rebuilt brilliantly after the Second World War. You know, Britain was also smashed to pieces. It had no money, people lost all the people they loved in the war. But they rebuilt a new society, a fairer society, with the welfare system that didn’t exist before.

So I think ordinary people like Mr Williams succeeded. It was difficult, but they succeeded. I think we have that knowledge. I think Kurosawa’s team did, and our society. For me, there’s a big difference in the term. Our film, I think, is more optimistic and we present a younger generation. So we can hope.

Q: In the film, Bill Nighy sings a traditional Scottish song called “The Rowan Tree”. In Kurosawa’s film, the song is “Gondola no Uta”. How did you come to select those songs and what was the reason for that?

KI: Well, as much as I respect Kurosawa, as much as I love “Ikiru”, the original film, there were certain aspects of it I found too direct. Often, the theme was being expressed too directly, with the voiceover at the beginning and so on. One of these aspects I was less fond of was the choice of that song, although the final scene of the Kurosawa film when he is singing, the singing is one of the greatest scenes in cinema history, I would prefer that the actual words of the song not refer directly to the story — you know, that life is short, and so on.

I felt it was more important that the song that we chose reflected the fact that he had a wife who he had loved and that there was a time when he wasn’t like this. Before his wife died, perhaps he was much more open, he was living much more fully. And I thought this was a very important part of this character. I wanted, with this choice of song, to suggest that he was deeply bereaved and that somewhere there was a memory of her when he was much more alive before he became “Mr Zombie”. So I wanted the song to connect back to his Scottish wife.

He sings the song twice. When he sings it at the end of the swing, it’s almost like he’s triumphant because he’s achieved the park, but also, he wants to be with his wife at that special moment. So I thought this would be an important moment. And my own wife is Scottish, and this is a song I learned from her. It’s not a song that I learned from records. This is a song that she learned from her grandmother and she often sings. So for me, it’s like a song that’s handed down through people, not a song that became a hit. I thought this would be good.

I also heard Bill Nighy singing a Scottish song in a movie a few years ago, “Their Finest” [dir. Lone Scherfig, 2016]. He sings a Scottish song called “The Wild Mountain Thyme” in that movie, and I thought, Yeah, Bill Nighy singing Scottish is rather good.

Q: Thank you.

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.