©Courtesy of Together films.

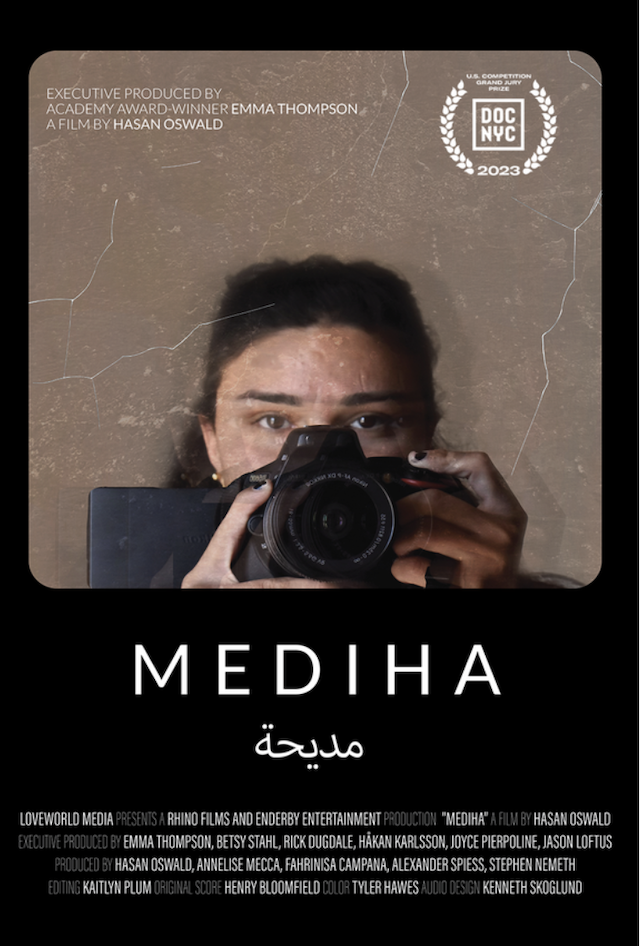

Mediha : Mediha and her younger brothers, Ghazwan and Adnan, were kidnapped in August 2014 when ISIS invaded their village of Sinjar in Northern Iraq. After years of enslavement by different ISIS families, they were rescued and returned to the IDP camps in Northern Iraq. Their parents and youngest brother are still missing, yet despite this they must now attempt to rebuild their lives.

Faced by local and international complexities, which continue to affect rescue and accountability efforts years after the genocide, the siblings must turn to a network of Yazidi rescuers in the search for their missing family members. Their story takes place over three years, across Iraq, Turkey and Syria, highlighting the ongoing and long-lasting impact of ISIS atrocities. Mediha takes us on her quest for justice, confronting her trauma and pain through personal video-diaries, and reclaiming her voice by initiating investigations into her perpetrators.

Director : Hasan Oswald

Producer : Hasan Oswald, Annelise Mecca, Fahrinisa Campana, Alexander Spiess, Stephen Nemeth

Screenwriter : Hasan Oswald

Distributor : Together Films

Production Co : Enderby Entertainment, Love World Media, Rhino Films

Genre : Documentary

Original Language : Kurdish

Release Date (Theaters) : Oct 11, 2024, Limited

Runtime : 1h 30m

©Courtesy of Together films.

Exclusive Interview with Director Hasan Oswald

Q: I heard that you went abroad to become an English teacher prior to making a film. So how was that process of coming around to making this film? Did you study any journalism or something?

Hasan Oswald: I graduated From Villanova University here in Philadelphia. No interest in film. A writing background, journalism background, but no interest in film back then. But this was the time of GoPros. So we had a little GoPros when we were traveling all around Southeast Asia and Europe.

And we would do little street interviews, with cabbies or food vendors. And I didn’t know at the time, but that was dipping my toes into what would eventually become a documentary film. I then moved to Barcelona. I still didn’t really have interest in film in general.

And I went to Lesbos, Greece to cover the Syrian refugee crisis with my GoPros as a little travel video. And that film went viral and national geographic signed me the next week. That’s a short version of how this happened.

Q : We all heard of the story of the Yazidi women and the camp. What was your first impression when you actually were there and filmed what’s going on there?

Hasan Oswald: Yeah. So I didn’t really have a real strong understanding just how dangerous it was at the time. I don’t speak the language. And also I had full trust in Dr. Nimam, who was the rescuer in those scenes.

She had probably been there hundreds of times probably. So I had full trust in her. Even though I didn’t speak the language, I understood there was danger. I didn’t understand just how much danger there was until we came back and edited the scenes with subtitles and then that’s where the quotes come up.

We’re going to shoot them in the head. And then pieces started coming out on vice news and whatnot of really horrific stories of acts violence committed in that camp, especially against journalists, NGO workers. Yeah, that was obviously the most dangerous part of this story and one that sticks with me in a pretty dark way.

Q : I heard that you guys initially contacted Mediha’s brother Ghazwan, he was very vocal about his family. Could you talk about meeting him and how that led to Mediha and her other family members?

Hasan Oswald: Yeah, sure. As you see in the film, Ghazwan has the charismatic spark that Mediha has and the other siblings have.

They’re wonderful kids. He was with Annelise Mecca, one of our producers was doing a photography workshop in the camp, it’s for only girls. He kept peeking in, curious about the cameras. Finally I said, “let’s meet him.” We met and interviewed him without a camera or anything. He said, “My brother hasn’t come home yet, my sister just came home.Why don’t we meet her?”

So we met the uncle and siblings, sitting in the corner was Mediha, already funny, already interested in the cameras. And she had this spark with her that despite what she had been through and we didn’t know, they didn’t speak about what she had been through, but we can guess, she had a spark of resilience.

I thought this is a participant, this is a character who can carry the load of…you know we split the filming 50, 50, and that was a big ask. And I saw that in her early on. Of course. I didn’t realize just how special it would become and how strongly she would grasp the reins of this story. But yeah, from very early on, I knew that this was going to be the thread we were going to follow.

©Courtesy of Together films.

Q : Your decision to give a camera to Mediha, how did you balance out the dynamic of filmmaking? Because in this case, the participant is also becoming a filmmaker in a certain sense. So talk about how you balance it out? How did you envision editing?

Hasan Oswald: Yeah, balance is the perfect word, I’ve always been interested in the power balance between filmmaker and participant, because forever it’s been heavily on the side of the filmmaker. interesting.

They take the story, they mold it, how they see fit, and they bring it to film festivals, red carpets. So I had always been interested in rebalancing that in some way, And that’s what led to the decision to hand Mediha and her brothers to camera.

I could never have imagined them being so good at cinematography and so innately, they understood storytelling. What we thought would be creative vignettes or transitions of home footage turned into,

They filmed their home, camp and around the camp. That turned into very quickly what you see now, which is close to 50 50 filmed by them and by me. And yeah, it was scary as a filmmaker who likes control, most directors do that because there was a big mutual trust in that collaboration.

Q : You made the right choice for this one for sure. What point did you also decide to focus on the rescuers? What was the process of finding them? Could you talk about how they work over there?

Hasan Oswald: The rescuers are mostly volunteer Yazidi rescuers. A lot of them had no experience heading into the work that they took on. And the work has changed. So what began as a government funded or there was resources from the government for them to bring these people home.

That dried up very quickly. A lot of it then depended on private donations and no pay for rescuers. That’s how it started. And then when we arrived, all those resources had dried up and there were pretty much no rescues going on.

Barzan was one of the last rescues since just four days ago when that girl was found. So they are pretty much not operating now, and that’s part of our impact campaign to start off..we want to kick the wheels on getting rescues started again. As far as how I found them, we weren’t breaking news, so it’s not like we were putting them in danger.

They’ve all been all over the news. I think with a story like this, the world moved on so quickly, I think the Yazidi people were very interested in focusing on getting some semblance of an international spotlight back on them. The rescuers were very interested in participating in the film.

And then again, with them, similar as we did with Mediha, we made sure that everyone was on the same page from day one. We weren’t going to show them a film full of surprises because there’s real danger in this region and we wanted to make sure that they were taken care of as far as the edit went. As far as their safety, not only on the release of the film, but moving forward. So yeah, it was a very open and collaborative process with the rescuers as well.

Q :You briefly talk about this, but what’s important of those stories is that when the genocide or massacre happened, people and media obviously focus those issues. But when the situation is going on for a long time, the media has left, and the people’s attention is shifted. So those are the things that are much more important to focus on, the situation of the aftermath. So what kind of things that the government or organizations are doing over there now? Could you talk about that?

Hasan Oswald: Yeah it’s, as Mediha says in her Q& A’s, the genocide was ten years ago, but the genocide continues. All of the issues that the viewer sees in the film are not only not resolved, and in most cases were worse. There is little appetite from the Kurdish or Iraqi government to solve things such as, the mass graves have not been unearthed, the identification of bodies has not happened.

So Mediha and her brothers don’t know where their dad is. For example, IDP( Internally Displaced Person) Yazidis in the camps are being…I don’t want to say force…but encouraged to leave the camps because the Kurdish government does not want to pay for them anymore. So kind of being pushed back to their homeland, Sinjar( is a town in the Sinjar District of the Nineveh Governorate in northern Iraq) and that has not been rebuilt since the genocide.

So it’s akin to forcing a people who just experienced the genocide back to the place where there is no safety. They fear this is going to happen again because it’s happened 74 times, 74 genocides committed against them.

In a lot of situations they were turned in, betrayed by neighbors. And right now there’s a huge increase in violent rhetoric online against the Yazidis. The situation is bad. And part of our impact campaign and part of the reason we made this film is to try to refocus the international spotlight on helping this cause and these Yazidis.

©Courtesy of Together films.

Q : When you guys have a sensitive subject to capture or talk about with Mediha, do you guys have a translator to make it clear what you guys intended? Because it’s a very sensitive topic that you guys are dealing with, particularly when you’re talking with Mediha. So could you talk about how you guys work it out?

Hasan Oswald: Not only we were working with kids who had been through a traumatic situation, and we were also working with a girl who had been through situations of sexual violence and at the time she was 14. So we knew we had to approach this not only delicately but we had to commit to Mediha and her brothers and her community.

This could not be a one year shoot. This had to be a four or five year project because that’s how you build trust and that’s how you have time to break down everything from, yes, we had a translator with her, but for anything, anytime she wanted to talk about something sensitive, we brought in female translators, her therapist what they called her therapist, and trauma informed producers.

We just had to make sure that if she wanted to talk about those sensitive subjects, we were there to support her talking about them, but in the right environment with the right guardrails. Continued consent and continuous consent were always at the forefront of every film, every shoot day intentional.

We want to do this as intentionally as possible. In order to safeguard against issues that could have come up. The time spent with them, overnights in the camp, helping with homework, family dinners. It’s just built this trust that we are not going to do her and her community wrong.

I always say, if you’re going to tell a story about a community or people you do not belong to, you better get it right. And we have huge support from the Yazidis community now. That took time and mutual trust.

Q: Speaking of therapists, do you find that Mediha was shooting those footages and families were therapeutic in a certain sense? And how is she now? Could you talk about that?

Hasan Oswald: She loves talking about this. She brings it up in all the Q &A’s. The camera, she says, was her therapist before she knew what a therapist was. It was a friend when she didn’t have friends, and someone to talk to when she didn’t have anyone to talk to, she describes it as a release off her shoulders, just from the first days of filming.

And that hasn’t stopped that sort of healing process through film. And while she doesn’t film anymore, what she does is, she speaks about her film, about her people, and about her cause. She watches the film. She sits in on every film festival screening. She says it’s a continuation of this healing process, and makes her feel good. What we gave to her as a tool in the hopes she would regain some semblance of agency has turned, we could have never imagined how well she would use that tool, but also how far she would come using the filming process and the film itself.

Yeah we’re super proud of her, no spoiler, she’s here in New York in school and making friends. So yeah it’s been a journey. Incredible journey that, as she describes, just started with speaking into this little lens.

Q : This movie won a jury prize at DOC NYC. How do you want an audience to take away from this film?

Hasan Oswald: Sure. Yeah. The film’s been on an incredible festival run. And now as we head into theatrical release and awards season, awareness of this issue is paramount to us, especially the 10 year anniversary.

However, as Mediha explains it better than I can, this is not just the Yazidis. This is not just Iraqis, Kurds, or even the Middle East, Mediha and her brothers are the human cost of conflict. The world moves on quickly. Mediha and her brothers do not move on quickly. So as Mediha says, “Every day there’s another Mediha in Gaza and Ukraine created by conflict.”

People do not see who the true cost of these conflicts lands upon, and that’s Mediha’s shoulders. People like Mediha’s shoulders. We didn’t make any huge political statements. This wasn’t about ISIS. This wasn’t about refugees.

This was a coming of age story in foot hills of Iraq, of a girl who experienced the unimaginable, yet they continue on, it’s a story not just of resilience, but it’s a story that I hope…these are troubled times in the world, I’m not naive to what’s going on in the world news, and so I just would love viewers to see, we tend to pay attention to these things as they’re happening, and we tweet and we post our outrage, then we forget about them…But Mediha and her brothers, they don’t forget them.

If you like the interview, share your thoughts below!

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.

invaluable insights into how we may better provide the continuing support for those who have lived violence, and who share their determination to heal and to advocate for healing and justice for others.

We in Bellingham look forward to screening this film during our amazing Doctober, at the Pickford Film Center, that provides our community a month-long worth of the revelatory power of documentaries