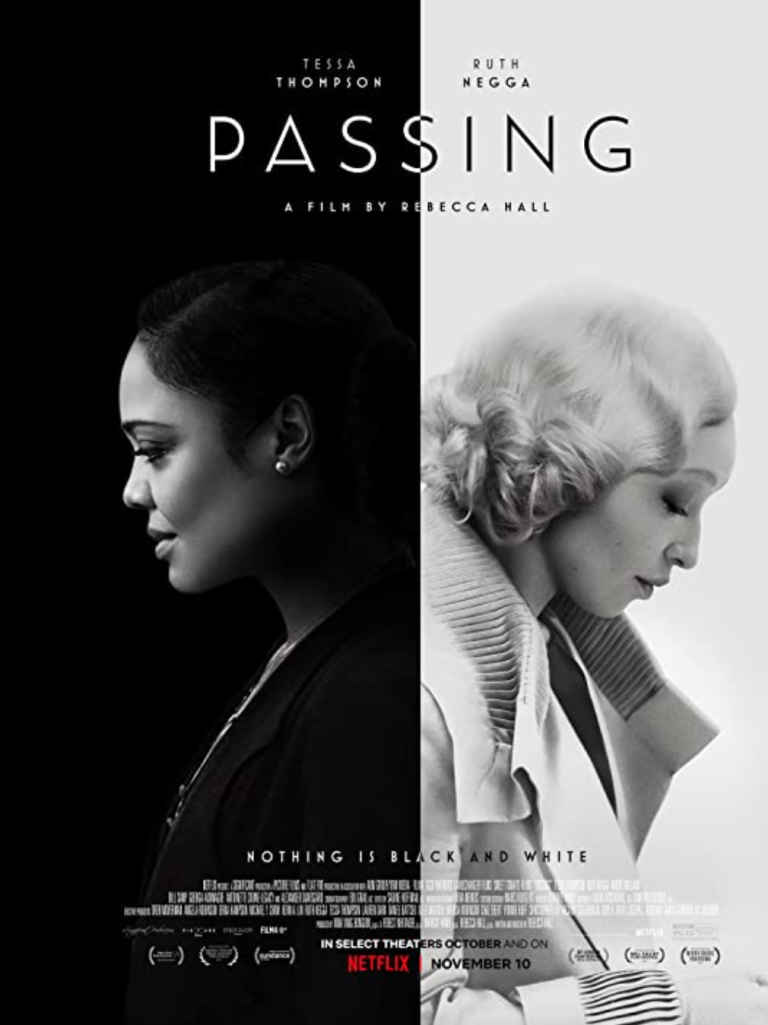

Synopsis : Adapted from the celebrated 1929 novel of the same name by Nella Larsen, PASSING tells the story of two Black women, Irene Redfield (Tessa Thompson) and Clare Kendry (Academy Award nominee Ruth Negga), who can “pass” as white but choose to live on opposite sides of the color line during the height of the Harlem Renaissance in late 1920s New York. After a chance encounter reunites the former childhood friends one summer afternoon, Irene reluctantly allows Clare into her home, where she ingratiates herself to Irene’s husband (André Holland) and family, and soon her larger social circle as well. As their lives become more deeply intertwined, Irene finds her once-steady existence upended by Clare, and PASSING becomes a riveting examination of obsession, repression and the lies people tell themselves and others to protect their carefully constructed realities.

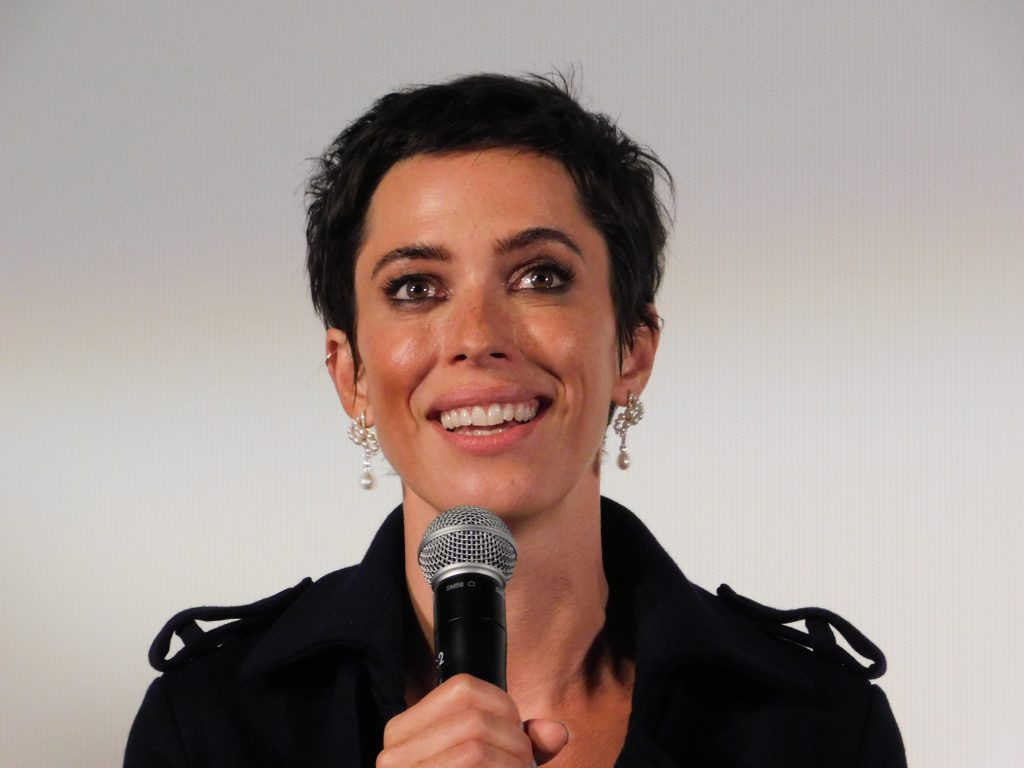

In this Q&A conducted with director Rebecca Hall and cast members Thompson, Negga and Andre Holland, they explore what it took to bring this project to fruition and poignantly discussed after this preview screening held in the Paris Theater.

Q: When did you realize there’s something here that you wanted to make into this movie?

Rebecca Hall : I remember specifically seeing the book in the window. Then I finished the book, loved it, opened my laptop, and started writing the screenplay. It was suddenly like being possessed. I think that I had freedom to do it because honestly, I didn’t think it would end up like this. Or I talked myself out of it.

Also, I was just struck by the modernity of this: how it speaks to so many aspects of humanity, in this tiny, tiny book. Now it’s not just racial passing, it’s all the ways in which the thing that you think you believe in doesn’t match up with the thing that you want. The ways in which we all put ourselves into containers or let other people put us into containers, and then we’re massively spilling out of them because nobody can be defined by one thing. That is a very contemporary idea.

We have words like intersectionality or something [like that]. I was blown away by that so when I arrived to work, I just thought I wanted it to look a certain way. I came up with ideas that shocked me when [placed] in the movie. I got really attracted to the screenplay, thinking, “I’m going to get into this because I’ll never make it. So it’s fine, this is just for me.” And then it was a 13-year process, maybe not quite 13 years. It was about a six-year process of me getting the nerve to take it out of the drawer, and then another six years of actually trying to get it made, which is normal.

Q: What was one of the early shots that you had in your mind?

Rebecca Hall : Of the feet. Also I had the idea of the meeting between the two of them. I committed self-matching at that scene. I had [that] in my head. I look at her playing the central character, and is she in a place where she was being observed, and you didn’t know why she was hiding from something, to a place where she was taken in this room and feeling safe, and then she’s looking around and suddenly there’s this other person looking right at her.

Q: In an interview you talked about bringing Tessa and Ruth to your house for a weekend before going into production because you felt that it would be imperative to have that time together. So tell me all about that: what did you do?

Rebecca Hall : Well, I’m an actor so I understand rehearsal very much, so I just kidnapped them and said –

Q: Was it like a rehearsal at the house, or was it bonding time connecting everyone?

Rebecca Hall : There were some. You and I sat down and did a lot of work. We’d sit down and go through scenes a lot. Mostly it was just time for the two of them to be together and explore each other’s [thoughts].

Q: Tessa, you said that you were terrified to take on this role. But you did it with such grace and depth, it was a beautiful performance. What ultimately made you say yes, what intrigued you about diving in?

Tessa Thompson : I guess I like being terrified. In the sense that I like to, when I am approaching work, there’s something that is central to the thing that I’m not sure that I can do.

In this case, it had to do with being in the character and also that there was this — so much is expressed, as Rebecca said, with her example of that panning shot of their passage. It focused squarely on Irene’s obsession with staring at her. Without the movie looking away, and looking back, there is no cinematic journey. So Rebecca was able to tease that out, and so I felt very comfortable. If she could do it…

What I was worrying about for myself is, there’s this incredible document in Nella’s words. There was a wealth and a depth of feeling that this woman has inside, and when you don’t have a lot of dialogue to express that, and also in that she’s playing someone that’s quite restrained, the moments when she’s feeling strongly is whenever she’s around this person and that stirs things in her— [which I had to express]. She’s a feeling person. How do you say that without saying that? And that terrified me. And then also other stuff terrified me, but I won’t go into that. But the easy thing is that she just needs to be really beguiled and blown away by this woman and look at her.

Q: Ruth, in bringing this really complex woman to life, what compelled you to play this woman?

Ruth Negga : I love the word “haunting”. I love it. I was haunted by this book. I was haunted by these characters, and I think what struck me most is, I never really read a friendship like that: the full, deep complexity of female friendship with all the usual attractions, and also repelled by one another at the same time, that push and pull. We have all combatted the disease of UJE: the ugliness of it, the jealousy, the envy. I was bewitched by these women.

For me, for Clare, I was so curious about this woman – her intention of living so fully and authentically. It brings to mind a Mary Oliver quote: “What is it you plan to do with your one wild and precious life?” Clare, for me, she embraced it fully and deeply. And I guess after reading it, I found – I don’t know, this atmosphere of sense of ending somehow that haunts the book and that lingers way after the final frame. I think Rebecca shocked us, and that’s a terribly hard thing to do. I don’t think I’ve ever seen film writing that captures the feeling, the emotion, having read it, onscreen, sufficiently.

Q: Had you read the book before anyone suggested you read it?

Ruth Negga : Yeah, I’d read the book. I’d wanted to work with Rebecca for a long time. We met up in New York and she said she was adapting this, and I [said] I’d do it anytime, anywhere.

Q: André, your character is so complicated and so rich. There are so many scenes that jump out at me when I think of them. But I ask you what I was asking them: what was it that intrigued you about this character, and do you want to explain it to the audience?

Andre Holland : This character gave me a chance to explore this world. I think that’s one of my favorite things about this job: getting a chance to learn about men I didn’t know before. I didn’t know about Nedda’s work, I hadn’t read that.

Q: In the dinner table scene, there’s an argument that you have with the other characters. It’s very much of that era, but also very contemporary. Black parents have had these conversations all the time. What was it like preparing for that and diving into that performance?

Andre Holland : Well, I was really looking forward to that scene from the very beginning. Which is exciting.

Q: Tessa, how was that exciting for you?

Tessa Thompson : What struck me is just that: how modern it felt. And this was before the events of last summer. But it’s like forever and always in this country, right? I think that’s the negotiation you make as a parent to black children and in particular, I’d say, to black men. So there was that on one hand, and to activate that which would do him a favor even now. And on the other hand, I think the scene has a uniquely important physicality that it felt like we were playing a piece of music together. To me there was a real specificity in rhythm. So that was what I liked.

Something that I really enjoyed about this project is the precision, I think, because of the precision of every angle. If you were off your mark by a little bit or just objectively not in the right place, Rebecca would come and be like, [gestures] “Once again.” But I don’t know — I like that. I didn’t do sports and I’m not into doing anything else. This is just something I like, so I’ll do it right.

Ruth Negga : You did, you know?

Tessa Thompson : And inside the form is such freedom when you know what the form is. When I was into Shakespeare and the Classics… But [Ruth] knows, go see her in “Macbeth” [on Broadway co-starring with Daniel Craig].

Q: Ruth, you talked about the precision of the technicality of the camera. How did that stretch you as an actor? How did you get that joy of finding freedom?

Ruth Negga : In order to play you have to have rules because it just tightens everything up. I felt a great comfort and relief in it because I think the way Rebecca works is a very lavish process. We were let in on this. This wasn’t a proletarian office. We knew that there was a goal as we were [performing], and we were recruited. And that’s a lovely thing, I think, about Rebecca, especially in her being an actor as well. There’s a gift in ensuring trust. That’s a lovely thing for an actor to have, a director’s trust, and to let us in on it. We had freedom to discover within the scene, working with Tessa and Andre.

Q: The framing is so beautiful. There is such a precision, and such a beautiful stillness in every shot. How did you arrive at that framing as the visual language of this film?

Rebecca Hall : It’s as I said earlier. An inherent problem in adapting this book for the screen is that if you were unable to show the inside of your protagonist’s mind, it would [belie her reality] because she’s not truthful to herself. That’s the whole point of this story. She doesn’t really know who she is. She’s so bound up in the idea of this respectful, proper, erect life – wife, mother, and everything – that there’s no room for her expression of herself.

So this was the bottom of that problem: How do you get you guys in on that? How do you show that? I think the formality of it felt to me, finally, correct, that there should be a way of slowly giving signals to the audience that this person is unreliable, and finding the visual language to do that. You slowly start to see what you are saying or she is saying it, maybe it’s not real. It’s fuzzy, it’s blurry, and you literally use lenses that compressed the image, but were soft on the top and bottom. That creates a sense of her world dissolving around her.

Also, it occured to me what I thought about this novel. The ’20s are famous for being loud – the Jazz Age, color, photographs — and there was something so — this book was so simple and held so much in it because it allows you to do the work. So I couldn’t help thinking about… What’s the simplest version of this? And that comes down to shot-by-shot. I didn’t want to have to cut away. So let’s see how long I can contain the two-shot. Let’s use a mirror if we have to. Let’s play a two-shot in the mirror with that person as well.

That formality also literally puts them in a box, it puts them in this place of restraint — Irene, specifically. It should feel claustrophobic. And, the music is deliberately beautiful, and haunting. It’s deliberate. So I was very specific about everything.

Q: It made us curious as well.

Rebecca Hall : Yes. Correct. Well, she was an exile for most of her life. And that song that you hear all the way through the movie is called “[unclear] Walker Rag.” I heard it when I was doing a rewrite at some point. Not right from the beginning, somewhere in the middle. I remember hearing that piece of music and thinking, “That’s the film.” That’s the time, that’s the feeling, and that’s the sensibility, and what we were looking for. If I can make this film sound like how this sounds, then it’s worth it.

Q: And the house [which was used in the film] was a character as well.

Rebecca Hall : Well, the house was pretty bright. I did want the feeling that the house was meaningful. It was meaningful to be there in Harlem, in that house, in a brownstone like that, knowing that these houses and these spaces, and the apartment that’s at the end of the film was a historic building. There were probably parties in the ’20s that took place in that building.

Ruth Negga : Yeah, I think so. The house, the residence, we learned a lot and we would use the bedroom as the place where we were all sitting.

Tessa Thompson : So we’d all be sitting in this bedroom together. It was a little claustrophobic. Which was helpful for me, because Irene was supposed to feel very claustrophobic. [I would go] “Irene would love this.” But the bathroom was open, and I could go in there.

Tessa Thompson: I was very happy for you except when I had to pee.

Ruth Negga : And it’s the set you want to work in…

Rebecca Hall : There were things that weren’t right.

Ruth Negga : I believe that when I’m not working, I’m haunted. I think the bricks, mortar and moulding carry memories. I am living there. All the memories that one would have in Harlem are so vibrant and so, of course, it is its own costume. I love that. So yeah, I definitely felt that. And it was all that for a lot of nothing [in the end].

Here’s the trailer of the film.