Synopsis : Severe, pale-eyed, handsome, Phil Burbank is brutally beguiling. All of Phil’s romance, power and fragility is trapped in the past and in the land: He can castrate a bull calf with two swift slashes of his knife; he swims naked in the river, smearing his body with mud. He is a cowboy as raw as his hides. The year is 1925. The Burbank brothers are wealthy ranchers in Montana. At the Red Mill restaurant on their way to market, the brothers meet Rose, the widowed proprietress, and her impressionable son Peter. Phil behaves so cruelly he drives them both to tears, reveling in their hurt and rousing his fellow cowhands to laughter — all except his brother George, who comforts Rose then returns to marry her. As Phil swings between fury and cunning, his taunting of Rose takes an eerie form — he hovers at the edges of her vision, whistling a tune she can no longer play. His mockery of her son is more overt, amplified by the cheering of Phil’s cowhand disciples. Then Phil appears to take the boy under his wing. Is this latest gesture a softening that leaves Phil exposed, or a plot twisting further into menace?

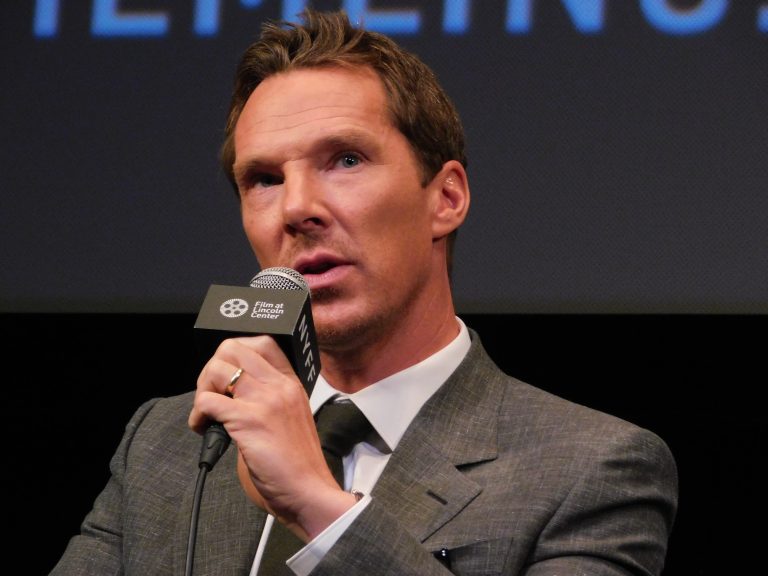

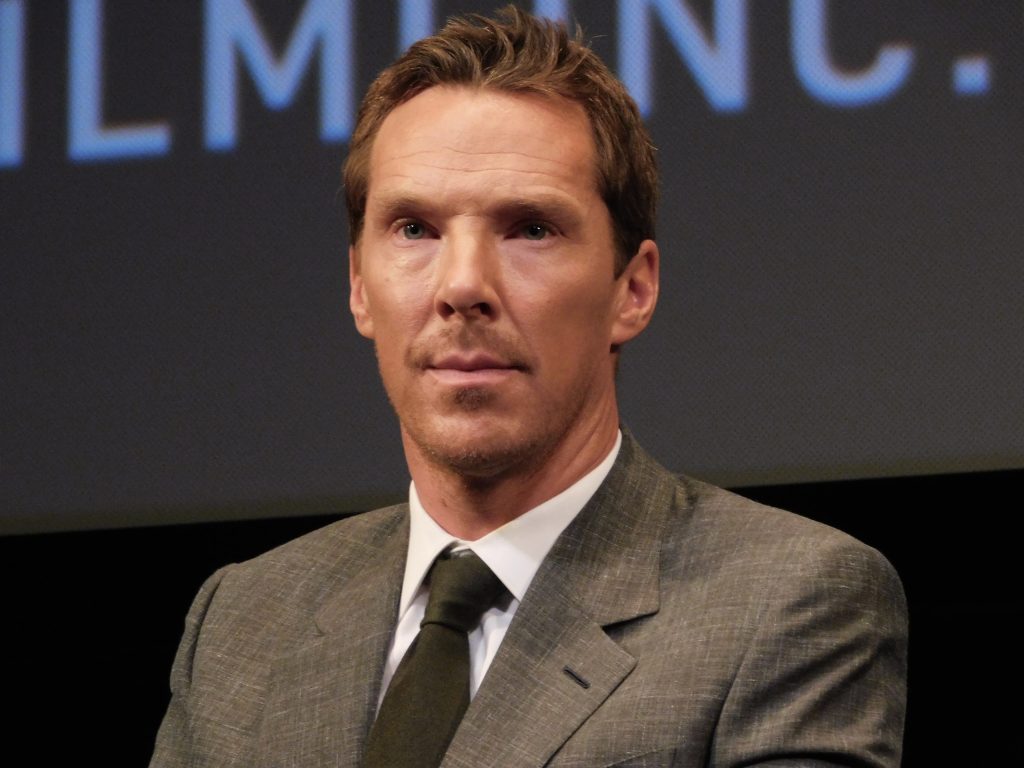

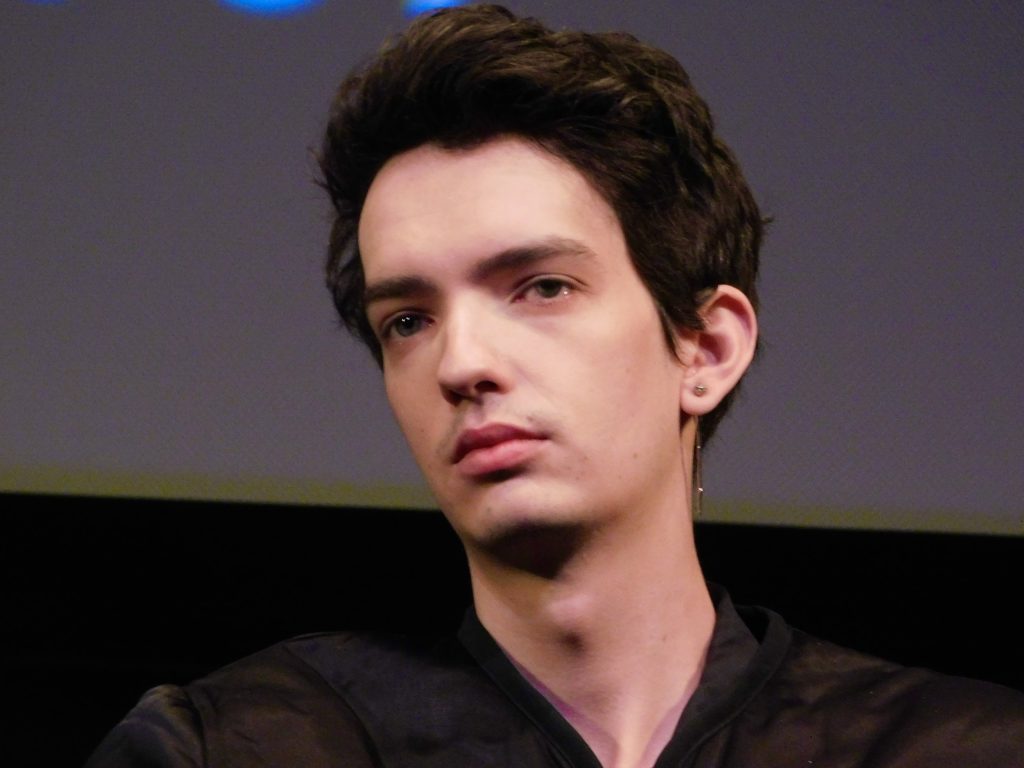

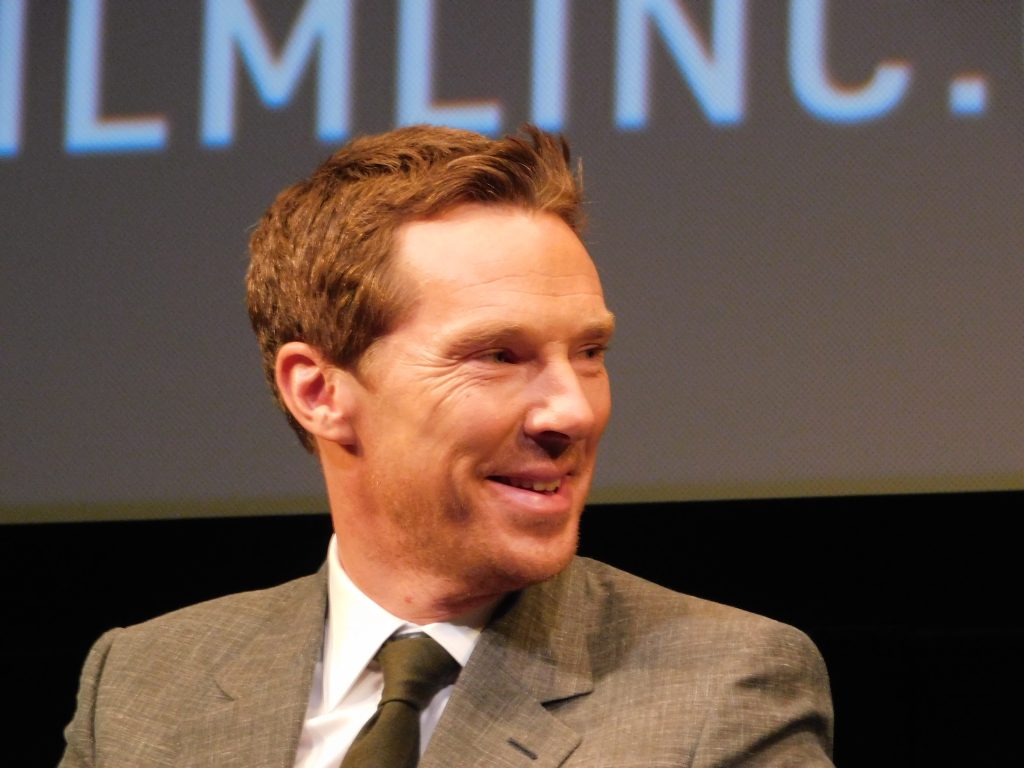

Q: Welcome to the press conference for our centerpiece film, The Power of the Dog, and the director, Jane Campion. Also welcome members of the cast: Benedict Cumberbatch, Kirsten Dunst, Kodi Smit-McPhee, and the cinematographer, Ari Wegner. Thank you all and congratulations.

I will leave plenty of time for your questions. But I’m just going to start by asking Jane to tell us about how you discovered this 1967 novel, that isn’t that well known.

JC: My dad’s second wife, Judith, is a great book reader – as a lot of New Zealanders are, actually – and she sent me the novel by way of, here’s a great book you might like to read. I was just finishing the Top of the Lake series and I read it, as you do a novel. And unlike many novels I read nowadays, I actually got more excited the further I got into it and found that the whole experience of reading this book was thrilling.

It felt like it was written by someone that really knew the world. At the back of the book, there’s actually an Afterword by Annie Proulx which is really helpful in understanding the context in which Savage wrote the book.

I didn’t think about making a movie or anything like that, but the point was that I just kept thinking of the themes in the story. Over the next few weeks, I really found it kindof haunting, in a really good way, and so I started taking more and more steps to find out more about it, like, were the rights available, for example.

Q: What were some of the themes that haunted you?

JC: Well, I think it’s clearly a really complex way of approaching masculinity because of its setting on a ranch, where it’s normally a place where the values of masculinity are really highly valued, and I think – as you’ve seen in the film – there [are] some surprises about what people are keeping secret. I think the pain of those expectations around masculinity – and I try not to use the words “toxic masculinity” – I think it gave such a great sort of container, in a way, for studying and thinking and rethinking about the men in this world. Because of course Phil Burbank is such an interesting study in masculinity, and also the character that Kodi plays, Peter, is another. He’s very feminine and of his feminine-ness he’s comfortable with it, in a way that [Phil] finds it really uncomfortable.

BC: Yeah.

Q: Did you all read the book?

BC: Yeah. It’s an amazing, amazing read. I always hope, in adapting a book, that one of the offshoots might be that people will pick it off the shelves and rediscover it, or discover it for the first time.

It’s got this amazing terseness in it. This poetry has a kind of savage, violent beauty to it, and yet it tackles incredibly complex themes in an era in which it was written in a very deft way that brings very loudly to a modern sensibility. He can surmise a character in a line, a story in a page, and a world in a chapter. It’s very beautiful writing.

JC: Yes. The book actually begins with a description of castration, which puts you right at the center of themes of masculinity. Of course, they don’t allow the masculinity of the animals to exist, just one or two bulls. The rest get castrated.

BC: I’m just remembering – I carry around the book with me quite a lot. I haven’t actually bought it, but it’s covered in dirt because I was the annoying actor bringing it to set all the time.

JC: He was the annoying actor on the set [laughs].

BC: I was always the annoying – well I was in character, so of course I was the annoying one. It’s a masterful blueprint, as far as approaching the role – for me, anyway. I found it opened up a hell of a lot of understanding of film, the complex building blocks that make him.

Q: Kirsten and Kodi, do you want to weigh in on the book?

KD: I feel like Jane added more to Rose, more richness than what was on the page, for me. So, a little bit book, a lot of Jane, and then me, myself and I.

KSM: I don’t have too much more to add, but of course there’s so many more layers and a lot more that you can explore, I guess, as a book, in the book. But as you said, there was a lot more depth and a lot more things that we could explore in our own little secrets that we could create as motivations and intentions for the characters in bringing it to life.

KD: Kodi and I had the secret that he killed his father. But that was our own secret.

Q: [to JC]: Did you know this?

JC: Halfway through, I was told.

KD: That was our secret creepy mother and son connection.

KSM: Yeah.

JC: They didn’t really do that, right?

KD: We did!

Q: Jane, you’ve adapted books for cinema before. I think even the films that you have in this [festival], there’s always been, I think, quite a strong literary influence. Can you talk about the process of turning this into a screenplay? I think Kirsten is right, that you do more with the character of Rose than is in the book. But there are other aspects that are quite faithful in terms of certain family dynamics and psychology.

JC: Yeah. I loved the book, so that was really a great help and a challenge as well. And I also worked with my dear friend and colleague Tanya Seghatchian, who was incredibly helpful in discussing the structure and what we might leave out and what we’re going to keep in. We decided we didn’t want to have flashbacks to another time, and try and tell it all in one time and make that a rule.

But the story is haunted by Bronco Henry, and he’s a character that’s very, very big for the story but who we never see. It was like trying to come up creatively with ways to have that understood or felt or discovered, which is easy in a book but really difficult [for a film]. Or things had to change and had to be created in order for us to be able to keep remembering how important this ghost lover was for a story and for Phil Burbank. I think in the end, of course, those themes of the ghost like for Kodi’s character Peter, that you know Phil is going to be his Bronco Henry. When you have to suppress your true feelings in your love, it’s safer to love a ghost.

Q: There’s one interesting choice I was going to ask you about: this voiceover that we only hear at the beginning and then it sortof drops out. Why have that only in the beginning?

JC: I wanted to steer people’s attention towards Peter because we see him only very briefly at the beginning of the film, then he’s off at school before he comes back. But I want them to know, in the back of their brains somewhere, if it works. I think most people can’t remember what was said, but I tried to keep it.

I had one more complicated version of it which I think had a lot of great texture, but you couldn’t remember it at all. But I think he’s just basically saying “You got to help your mother”, and that might trigger a memory later. Just to know this isn’t just going to be a story about two brothers that are not getting [along] anymore.

Q: The other thing about the book is that it is often described as somewhat autobiographical. So I don’t know if you did much research into Savage’s life, and into Montana and that period.

JC: Yes, I did. Annie Proulx really opens that up in the Afterword that she wrote in the book. And then we also met relatives of Thomas Savage when we went and did some research and actually saw his ranch that he grew up in near Dillon in southwest Beaverhead, Montana.

So he came to the ranch in a very similar way to Peter, like his mother married Brenner. At that time, Ed Brenner is actually the inspiration for Phil Burbank, so there [are] quite a lot of similarities. We did actually ask, is there someone who might have been Broncho Henry? And they did show us a picture of the person that they thought could have been that inspiration as well.

So Savage was a gay man and he, at that time, wasn’t obviously openly gay and he actually married. I imagine that you know when I see the photo of his and the jacket cover, he’s wearing the tennis shoes. That is so important in the profile for Peter for me, so I imagine he thought of himself as Peter in a way.

But he also was a great horseman and broke horses. Actually, his first thing he wrote was about the breaking of a bronco. But he certainly did have a much more complex relationship to the romance about the West than most people did.

Q: Since we have the [actor] here, I was wondering if you can talk about assembling this incredible cast for the film. Maybe we can start with Benedict in the role of Phil. This is a quite different part, I think, from anything you’ve played. I think it’s a very complex role. What made you think of Benedict for this part?

JC: I was thinking, of course, of “Who could it be?” and Benedict is somebody whose work I’ve always really loved since I saw the Ford Madox Ford [series] “Parade’s End”, and then your recent television series as well, which is amazing. I just think he’s a really good actor, and that means a lot to me. Looking for somebody that can take on this part without worrying what everyone’s going to think of them as they play a really cruel man. But you need someone who really wants that challenge.

Benedict, you’d read the script, I think you said, or you were interested and that meant a lot to me. So we met, didn’t we? Also, I think that Benedict has got this fantastic quality for showing actual ability to show vulnerability, which I think is so important for people connecting to a character like this. It could have been like you’ve been so put off and just went “Oh, I don’t know about this person at all, I don’t want to know anything more.” But somehow Benedict managed to bring you into the inner world of the character in some sort of compassionate relationship with his pain.

BC: Thank you. It’s very weird having Jane Campion talk about you like this, but very nice at the same time. Thank you very much.

Q: Can you say a bit about preparing for the role? Obviously, there’s quite a few technical skills you had to pick up.

BC: Yeah, I won’t bore you with a list of those. A lot of them didn’t even make the film – some ironmongery and taxidermy that didn’t make it. But whistling, whittling, horse riding, banjo playing, it was a lot — roping and ranching in itself. All of that. For me, it was about trying to – time capsule, I suppose – to imagine myself back into that world, which required a lot of subconscious work as well as conscious work, just sortof drip feeding the imagination over a long time. Jane gave me quite a lot of runway with this, which is a rarity in my life [and] which is a blessing for this role. Because it was quite a sharp turn from a lot of things I’ve done before.

How I started: well, I went to Montana. I did a sort of dude camp thing, which was great, to try and get the dirt and the blood and the sensation of what it must be like to be a body in that world doing that work with animals and people and that culture. A lot has changed since then, obviously.

But then it was about leaning in near a production to costume and Grant [Major]’s work, our production designer, and Noriko [Watanabe]’s and hair and makeup, with Jane collaborating to piece together a kind of thing that felt good to move around in and to see my environment and understand it.

But yeah, all the time I felt like I was reaching, and then those lovely moments when you stop reaching, you just let go. Jane’s brilliant encouraging you to do that, to stop worrying about the homework and just be, and let vulnerability come and something unspoken, which you can’t really talk into a microphone about, happen. And there was a lot of space and time to do that which is, again, a rarity. That’s all credit to Jane’s female gaze, but also her sensitivity as a human being and where she was directing the story, and Ari’s lens work, and everything else going on around it.

And these amazing actors, one of whom is not here on the stage, Jesse Plemons, whom many of you might not hear, but Jesse in particular as my brother, to form a relationship, however odd and competitive it was, with Kirsten. We hardly talked because we were in character all the time. So once I’d done that work, I was trying to be him all the time. So we’re good friends now, but . . .

KD: We were friends on the weekends.

BC: We were friends at the weekend, it was very weird. I didn’t take my homework home with me. That is homework – I didn’t have my work home with me.

I’m very jet-lagged after only a four-hour time difference from L.A., but I’ve just realized –

KD: It’s worse coming [east].

BC: — it’s weird, right?

KD: Because it’s like, oh, you’ve got to wake up at eight –

BC: — yeah, and it’s sortof four in the morning or whatever. So forgive me, I’m dribbling in my mind and in my body. But —

KD: — but air conditioning is kindof quiet here –

BC: Yeah, it’s so respectful, it’s such a New York audience. I love it.

But yeah, I think I’m living up to my gold standard of sending people to sleep. Apparently, I do audio books that send people to sleep; so if any of you suffer from insomnia in the city that never sleeps, just do click-out. Maybe I’ll do a read of the Savage novel, maybe that would be a way to lull yourselves to sleep after this. Thank you.

Q: Jane, why don’t you talk about the other actors?

JC: Yeah, I wanted to also mention Jesse Plemons because he’s not here. But that was an absolute joy to work with him, and then you were really excited, too, Ben, to work with Jesse.

BC: I didn’t cast this film – I tried to. I did, I really pushed for Jesse. He was the only person I imagined in the role from the beginning for some reason. He was just there.

JC: But Jesse wanted your role.

BC: Everybody wanted my role.

JC: I think it’s beautiful to work with an actor like Jesse, and I of course had noticed his work already. But when you’re really there with him, he’s such a unique human anyway, and such a unique actor that he takes you two degrees more grounded into a character than I think you really ever see anywhere else.

Jesse also had to try and get my hyperactivity into a zone where you could actually get to talk to me, and he sortof worked me and then he’d get me into the caravan and say “Oh, you know when you did this or that, you know, it wasn’t so pleasant.” I was so grateful that he would talk to you, and work on the friendship and the relationships. So I ended up loving him to pieces and feeling really connected to him.

This job, we’re all doing quite complicated, difficult things and everyone feels quite vulnerable. So it is a job to make these relationships work, don’t you think? I’m completely willing, because I know how much you guys put into [it]. Anyway, we’re sorry Jesse’s not here.

KD: I’m the most sorry, believe me. We’d be away from our kids, in a nice hotel room.

JC: Shall we talk about working together?

KD: Me and you, Jane?

JC: Yes.

KD: Yeah, well, Jane wrote me a letter in my early 20s about working together. I saved it, and obviously, she is one of my favorite filmmakers. Her films were always something to kindof inspire myself as an actress with the type of work I’d like to do in my own career. So Jane has always been one of the people at the forefront of those kind of performances for women.

JC: I thought I really was in love with the work that you did with Sofia [Coppola] right back to “The Virgin Suicides”, it was so mesmerizing and beautiful. And then to see you in “Melancholia”, oh my god, that was a brilliant performance. And then to find out that you’ve got the same birthday as me, as does Lars von Trier! This is how women work together. And then we sometimes talked about the role, right?

KD: Yeah, we did.

JC: Kirsten says to me “Don’t worry, Jane, I’ve got this. I’ve got it.” There was a lot of difficulty, actually, playing a drunk person or a person that was drinking a lot.

KD: Yeah. I think you told me to have Jesse – she’s like, “Any time you drink, just have Jesse record you.” Right? I mean, we did it, believe me. That was helpful.

Q: Kodi, I think was a discovery for most people in this film.

KSM: I originally auditioned for Phil, actually. Everyone wanted that role. Didn’t get it, so that’s okay. Peter [is an] extremely layered character. Originally reading it, I wouldn’t have suspected that because he’s somewhat on a secret mission until like the last ten pages. You really see that he pulls something else off, which is really what attracted me to the role. And had me reading the script immediately again after the first time that I read it, just to go through and make sure that that’s what I just experienced with this character. So I saw that there was a lot to play with and pull from and it would be an extremely challenging role, but a lot of fun as well.

After meeting Jane, I absolutely fell in love and I feel that she saw a certain potential in me that she could kindof push me out of my comfort zone and the boundaries that I originally had in terms of character development and all that. And that’s what she did.

JC: Really? Tell me how. I never realized that.

KSM: Absolutely. I mean, it’s been something I’ve spoke about a lot, and it’s unfortunately been sound-bitten sometimes in some of these interviews and it sounds like I said “She made me extremely uncomfortable.”

I didn’t mean that at all. But no, just in terms of creativity, we all, I guess, have our approach, and when it comes to developing a character and creating a world for the character and understanding. But I feel like if I went on this endeavor with just my own tools and my own approach, then it wouldn’t have been anything near what I saw on the screen and the performance that I’m so proud of. Thanks to Jane, I feel like you took me through a lot of different techniques, and nitpicked and pushed me out of my comfort zone in a good way.

JC: This is a very modest young man, because when he arrived, we just jumped straight into an improvisation. I came in the door and oh my god, he looks like Peter. So I started to pretend like I was interviewing you or something as Peter. Neither of us quite knew what was going on, but we went along with it.

KSM: Yeah, we did. I believed there was supposed to be sides or something, and I thought it was a general meeting and we met there and we just –

JC: So I just pretended he was Peter and was asking about his mother, and questions, and immediately I could see how brilliant Kodi could be as this character. I was so excited, I mean, he was already fantastic. I was thinking “Oh my god, we’ve got a Peter that’s better than the Peter in the book!”

KSM: That’s so sweet. No, I am in love with his kind of more grounded, less murderous side. I relate to that. He’s an intellectual, he’s a hermit, he’s very alone, and he studies life and he’s passionate about life, and he’s extremely curious. One thing I really love about him is he’s extremely courageous and confident in himself.

Being someone who’s extremely kindof a feminine myself, I feel like there was a lot I could take on and learn about him, and things that I had to experience in my own life. My dad’s six foot six, bikey, covered in tattoos, and that was something that I knew I was never really going to grow into or be. I had to really embrace who I was in that same way that [Peter] did. So I really enjoyed playing that.

Q: I want to bring Ari in, and then we can take questions. This is your first time working together? Ari and Jane?

AW: We’d actually met briefly. We did a commercial. It was a very short shoot, but this is definitely a journey we’d not been on before.

Q: In case people don’t know, I think Ari has shot some of the most striking films of the last few years, like “Lady Macbeth” and “In Fabric”. Jane, can you talk about deciding to work with Ari on this one, and figuring out the visual language for the film?

JC: I’d also say some shorts, Ari’s shorts, that I thought were really incredibly beautiful. The camera language in it was stunning, and having worked with her on the short, it was like a little icebreaker, really, wasn’t it?

AW: Yeah.

JC: And I felt, okay so this is a very masculine story in the way that I’m telling here, and I don’t want to abandon all the ladies. I thought, oh, I’ll have a female [DP] and so wouldn’t it be brilliant if it could be Ari? And we could go on this adventure together. Ari was really open to the idea of a really, really long pre-production, which I think is absolutely vital in giving any project its full legs. We both knew it was a big stretch for both of us, I think.

AW: Yeah, but it was incredibly enjoyable. We started about a year before we shot, knowing more or less the location where we might shoot. We wanted to see it at the time of year we were shooting, so that was a whole year before the cameras were rolling. We were walking up hills and down valleys, trying to find the Burbank ranch, find the mountain range that could be so iconic.

And like you were saying about the relationship, just getting to know each other because a film shoot is quite an intense experience and it can be so lovely when you’ve got a friend and ally versus someone you’ve really just met six weeks ago.

JC: Yeah, I think we made really good friends. I love Ari, she’s amazing. We also spent a long time discussing the language of the film that we wanted to use photographically, and trying to describe it and trying to think about it. And I think we got there. We never quite put words to it, did we?

AW: No, . . .

JC: We also talked a lot about the characters and Ari’s a [DP] that works from a deep interest in character and in story, which is lovely. And to me that’s – when the visuals are really embedded inside the mechanics and the themes of the story, everything, then they’re so much more meaningful than just looking beautiful.

AW: Yeah, I think the most definition we got to was for every frame, know what the information was and to have absolute clarity of information, which seems quite simple. But to know what that information is is quite a lot of attention to detail and work to know what is the information at what point, which seems simplistic. But to do that, you need to know everything there is to know in the script to make the [right decisions].

JC: There’s the other side, too, which is not intellectual at all, like the work that you did with Benedict in the sacred place with the scarf where it was just me and you and Benedict and we didn’t really know what he was going to do next and just had to be highly intuitive and sit in a situation where you could try things.

BC: Yeah. With Ari there was a huge amount of freedom with that, to ignore the trappings of a camera following your movement. I felt unobserved. I felt free to do what I needed to do in the space and see what happens.

AW: Yeah. I think that’s one of the amazing things about you, Jane, that you allow everyone to be vulnerable. I think the three of us were all in that kind of willowy glade at that point. We’re all vulnerable and open to not knowing what was going to happen but to know that there’s no such thing as a mistake, that there’s just [to] take a risk. I really love that sequence, it’s one of my favorites in the film.

JC: I think you’ve got to take risks and you’ve got to trust, and there’s really no other way around it.

Q: Okay, let’s take some questions from the audience. Jane about working with Jonny Greenwood on the score:

JC: Jonny Greenwood is a genius. It’s an absolute pleasure to go through the process with him and he really led it. After I heard a piece that he did called “Water” with the Australian Chamber Orchestra, Richard Tognetti, [et al.], I didn’t even know it was his. I am a fan of his anyway, and I [said] “What’s this? I think this could be for us.” It turned out to be Jonny Greenwood again.

So we got an exemption from Financing in order to work with Jonny, because I really felt we needed someone with his depth as a composer. I think he’s extraordinarily talented. What he basically did was, he built up a lot of suggestions. I was really just sharing what he was going to do because he’d say “I like horns” or “What about mechanical pianos/” and “What about violas?” And I would just [say] “Yes, yes. Try whatever you like.”

He created a palette of what he was feeling from the script. My experience is, it’s much better for composers to work off their own instincts and intuitions and not actually have the film trying to fit themselves into that. So he created a suite of pieces that he felt [with] complete freedom to create.

We maybe had in the end about 30 or 35 of these pieces, so that when we started editing, we started fitting them to pieces and parts of the film, and then we’d share that back to him. But we might be struggling with one or two cues that we had really high hopes for, and then some surprising things happen, like we’d use half of one and half of another and they just sortof worked and he could bridge them.

But it was a very interactive process, and after that, any digital sketches that he made he replaced with actual instruments as much as possible. He’s so modest and so easygoing, I was sortof [afraid] to ask for things, “not sure he quite got this moment”. He’d say “Oh, great, give it to me”, like oh great, I want to do some more violins or I want to try this or I want to try that. I want to do some more strings. He really enjoyed any sort of challenge we threw his way. He was beautifully modest.

We’ve been putting a book together about the making of this project, and we decided to include the emails between him and me during the process. And Tanya [Seghatchian] was also involved in it, too. She actually plays piano, and I don’t read music or do anything, so I feel quite vulnerable talking to composers at times.

But he was never like that. He never made me feel less or anything of that kind. But it’s really interesting because we haven’t met. In fact, we’re going to meet in London for the first time because of working through the pandemic. It’s a very, very different situation. It probably suited him really well because he’s quite shy. So we had this massive Zoom relationship and email relationship where I’ve become very, very fond of him. And I love what he gave us for this film, and how it sits in there with it. Thank you.

Q: “Earlier, you said you were trying not to use the phrase “toxic masculinity”…

JC: You hear that phrase “toxic masculinity” so much that you begin to wonder if it means anything. I think we do know it means something. I am really interested in both concepts of femininity and masculinity and how they play out in our lives because I believe it’s in everybody and we all have both.

Also, when we deal with alpha males, it’s painful. They’re so dominating. And I am interested in that because I have to put up with it.

Q: I suppose, maybe to follow up on that, a lot of people have pointed out that this is your first film that focuses on men. But I do think that masculinity is a theme that you have explored in your films, so I don’t know how much you see this as a departure from the other films.

JC: I do see this as a departure, in fact, almost like a bookend. If you look at “The Piano”, you’re clearly looking at much more from a much more feminine perspective. I see this as a kind of bookend of another large landscape film, exploring another kind of masculine myth. Savage has helped me find a piece, really, that I could feel really happy [about] and it took me a little bit to find my feet in it.

But also, you know, I did a lot of psyche and dream work just to help me really explore that. Because I didn’t want to stand back from it. I wanted to really go in there and from my point of view, if you imagine what Phil was feeling and they’ve been so suppressed, you know.

It was a challenge, and once I got in there and got dirty with it, I really enjoyed it. And also, I think the male actors that I’m working with, they’re my friends. Friendship can [outrank] everything in a way, I think. There’s a way where we just accept each other as individuals and personalities

[to Cumberbatch]: What do you think? Does it make a big difference being directed by a woman?

BC: I wasn’t gender aware, do you know what I mean? I’m just working with a really talented director, and someone who I trust. Of course you bring a sensibility which is about your life experience to your work. I have worked with female directors before – not as many as male. But I’m very glad it was you directing this film –but your entirety, not just your gender. That’s all I can say about it.

JC: Thank you.

Q: Jane, you mentioned dream work. Can you elaborate on that?

JC: Yeah. I was trying to figure out a way to – I actually felt quite a lot of fear before getting into the business of directing it and understanding these characters as well as you could because it’s a real thing for me.

If I’m going to do something, I want to do it as well as I possibly can. I can’t stand the idea of not giving this project what it needs. I had the strong feeling that I needed to do some psyche work to get inside it and to really feel what, especially, Phil Burbank was feeling and thinking. So I worked with this woman called Kim Gillingham, who encouraged me to have these dreams, and it was the most amazing work I’ve ever done. She’s the only person I think that’s really helped me as a director to go very deep. She facilitates this dialogue between yourself and the character. So all the things that you say are only the things you say.

KD: Yeah, it’s kindof like therapy between you – for me, it’s like therapy. I do the same work, but with someone named Greta Seacat, who Jesse and I work with. We also do dream work.

JC: Well, actually, that’s Sandra Seacat’s daughter, right?

KD: Exactly, yeah, so she learned from her mother. But it kindof feels like therapy between you and the person you’re playing. So at the end of the day, you know who you’re playing better than anyone else, which gives you a sense of groundedness in your work and also a sense of security to try anything again.

JC: That’s actually really true. Having done the work, I did feel so much more grounded and confident that I understood.

KD: And your choices then are completely, like, right on. Like you never will question yourself when you’re filming.

JC: Yeah. Because it comes from such a sacred deep place in yourself – the images, and you can’t make them up, can you?

KD: No.

JC: It’s a gift from somewhere else

KD: Right. Your unconscious mind.

Q: Okay. Question from somebody who is from east Montana: question for Jane and Ari of conceiving of the landscape as a character. And we should add that you found these Montana landscapes in New Zealand. And then questions for the actors about working against this landscape.

AW: It’s a big, big question but yes, we did shoot in New Zealand, which sounds like a good stand-in. We spent a long time thinking in depth about finding the right places. I’m sure everyone has their own personal connection with the landscape in this film. But for me, that sense of scale in isolation was mainly important, [with] obviously the sense of place, and Phil’s relationship to the mountains and the dog. But the way I looked at it as well was how important it was to set up the scale in isolation.

I think also, for Rose when we meet her and she comes to this place, by the time she arrives, you as a viewer know what kind of place this is and how remote it is and how much trouble she is, that she’s not going to get out of there in a hurry. That was my way in to set up the epic-ness, the scale, the brutality, the remoteness, for that kind of very particular reason.

JC: Well, I’ve come to it from a bit more of a sensualist point of view. I think the hills are really sexy – all those folds and crevices hiding secret little streams and things. I’m in love with landscape in a very powerful way. It can get me trembling. I just love it.

I also agree with Ari that I did feel like these people were in the middle of an ocean, really, they were so isolated in the landscape. Of course, I did go and see the landscape that is Savage’s landscape in Beaverhead, Montana, and that’s amazing as well. But actually not so amazing as on his actual ranches, I think, [in] the hills that we were filming with in the Ida Valley. New Zealand is a really weird place, it can stand in for almost anywhere – like Middle Earth and a Switzerland; now, Montana. It’s a chameleon; it really is a landscape actor.

BC: It is another character. It is, completely. Phil is the landscape; it’s in him. He’s the outdoors, he brings the outdoors indoors. For me, I had to literally lay in the earth for a while — just feel it, hear the grass, see the clouds move, feel the different temperatures. So I went to set a few times before we started filming.

I did a lot of that in Montana as well when I was out there. It’s hugely important. It’s something that [Phil] has managed. It’s one of the only aspects of his life that he has total control over: this outward show of masculinity, where he knows how to work the land and the people of the land and the animals. In any condition, in any landscape.

To be able to get that familiar, I’m outdoorsy; that’s definitely a box ticked as far as something I have in common with my character. I love nature, and that immersion, I think, was key for me to find him. So it was my ally. I felt it was something for nothing to have that as a backdrop. I was panicked about stepping out into a car park in Auckland doing set work. I was really worried about it because it felt so natural being on that plain under the shadow of those hills. Yeah – we got there.

JC: I think, too, that when I see the film now, I really see how Phil relaxes in nature. You only really see him calm, without all the masculine front that he puts on for the other cowhands, the alpha performance.

BC: The secret space is outside, his sacred place is outside.

JC: Yes. He’s at his most loose, relaxed, natural, beautiful.

Q: All right, we’re going to take one final question: [how did you conceive of the panning shots that bookended the film at the beginning and the end?]

JC: I think these sorts of visual rhymes are things that we’re always aware of and looking for without setting them up in some sort of fake way. [Ari and I] were very aware of it, and we were discussing how it would work, like to open the story with that and then to end with [Phil] quite a broken man, looking for the boy with the rope on the way to the hospital.

As I said before, you’re always looking to try and find a language that will hold the film in a way that you can take it with you, that you will remember it. That will help you review it in your mind later.

For me, that was one of those rhythms that I thought would work. Well, although it was quite hard to get it, I almost gave up.

AW: Because it was very tricky.

JC: Your team [was] brilliant. I was going “Oh, this isn’t going to work.”

AW: Yeah, one of those ideas that you have when you’re sitting at your kitchen table with a nice cup of tea and drawing thinking “This will be a great idea”.

JC: It’s quite hard to achieve. You’ve got to have the track and then the panning and everything, and then they’ve got to be walking at the same pace.

AW: Yeah. But I remember one of the things [we were] talking about was to make sure that we obviously have kind of emotive images, but not emotionally manipulative camera moves. So we had a rule about no camera moves that were emotionally manipulative. And we wanted a hands-off kind of photography that you can watch someone feeling something, but the film’s not telling you as an audience how to feel about that. It doesn’t guide you or tell you or prescribe to you how you should feel about it. We just show you.

JC: That was very important to both of us, and for me as a director I really love being given that space. I don’t want to be told how to feel emotionally. I always react against whatever I’m told to do. It’s been like that since I’ve been a kid.

It’s really beautiful when you see a film [that way] and I’m happy if this one gave you that feeling, too, that you can have your own feelings freely without a sense of being manipulated.

Q: Kirsten, were you going to say something?

KD: No, she [the audience member] just commented on something really nice that you guys answered, which was that Jane invites you into a film rather than tells you what to feel.

JC: I think that way, too, you can go back to the film and see it again, and notice different things. There’s still a space that you can explore because there’s more than one way in and through.

AW: Yeah. I remember you, Jane, and us saying that we wanted the film to be a strongly retrospective experience. You experience the film in real time as you’re watching it, and then hopefully, afterwards your experience somehow continues with your thoughts. I think that also comes from a film that’s not telling you at every beat “this is how you should be feeling”. It’s up to you to take what you see and put your own experiences and thoughts onto it. I know the first time I saw it, I was very biased, but there’s days of images and thoughts coming back to you.

JC: I don’t think you’re that biased.

BC: As an actor, though, I think I speak for all of us: when we watched it, we were like “Ah, that’s the film we’re in”. And that’s again, even as someone who knows what we’re trying to do in our way, to be invited in as an audience to have a spectator’s experience when you’re watching your own work is a very, very rare testament to the masters on this stage.

Q: All right, I think we’re going to have to wrap it up. But I want to congratulate and thank all of you for being here.

Here’s trailer of the film.