Press conference with Director Chinonye Chukwu, Producer and co-writer Keith Beauchamp, actors Danielle Deadwyler, Whoopi Goldberg, Jalyn Hall, John Douglas Thompson, Sean Patrick Thomas

Q: Keith Beauchamp had been working on this story for a long time. He made a documentary about the Emmett Till case. How did you develop an interest in doing a story about the case? What was the origin of the film for you?

CC: Three years ago, the producers — including Whoopi, Barbara [Broccoli], Fred [Zollo], Michael Reilly and Keith — reached out to me and wanted to know if I was interested. This was not too long after I had finished screening my last film, “Clemency.”

Barbara reached out to me a month or two after it premiered at Sundance. I didn’t think I was in the emotional space to make this film, but Barbara was persuasive [laughs]. So when I met with them, I was thinking, “All right, I’m going to come clear about the kinds of parameters and non-negotiables that I am only willing to work with.” I was actually expecting them to say, “That’s fine, nice meeting you. Goodbye.”

But when I met with the producers, especially Whoopi who was so warm, I felt so seen by them. They really respected my artistry. So I told them: “First and foremost, the only way I’d be interested in telling this story is if I rewrite the script and focus my directorial vision towards this being a story about Mamie, her emotional journey and perspective. The narrative is really going to be through her lens primarily. The producers were like, “Yeah, yeah, okay, great.”

Then the second one was that I didn’t want to show any physical violence inflicted on black bodies. That was a non-negotiable for me. They were like, “Okay.” The third one was that I wanted to begin and end in a place of joy and love. In addition to this story being about Mamie’s journey, it’s also a love story between Mamie and her son.

They really gave me the space and creative freedom to tell this story the way I believe it needed to be told. So it really started from there. I was fortunate in that Keith was a mentee of Mamie’s and he was doing so much investigative work and helping to reopen the case. He had a treasure trove of information and research that he passed on to me.

I was able to really take some time to ingest it all, and go a few times, to Mississippi and Chicago, where I spoke to a lot of different people. That really laid the foundation for me to dive in and rewrite the script — in a very short period of time — and then direct the film last year.

Q: [To the producers] What was it about “Clemency” that made you reach out to Chinonye and consider her as the director?

KB: I can start. It was the way she told the story, that intimate, character-driven story. It was something that we wanted to see with “Till.” Mother Mobley was a strong figure in my life, and was most important to be able to resurrect her onscreen and tell her story. That was one of the main reasons why Chinonye was chosen to direct this.

Q: Having done a documentary, what did you think about making a fictional version of the story? Why did you want to develop it?

KB: Chinonye made sure that she had the story locked. Coming from someone who researched this for 29 years, and being that I’m so close to the story itself, and everything I wanted to see onscreen was the whole story.

Of course documentaries are different. Chinonye quickly checked me on that — “Oh, you can’t do this, we can’t put all this in the story.”

CC: I’m a teddy bear.

KB: It was a good experience to understand, because this is my first major feature narrative. I can do documentaries while I’m sleeping. But this is a whole other ballgame, so being able to figure out what would be great to have onscreen and what would not — that was a challenge. But we were able to do it.

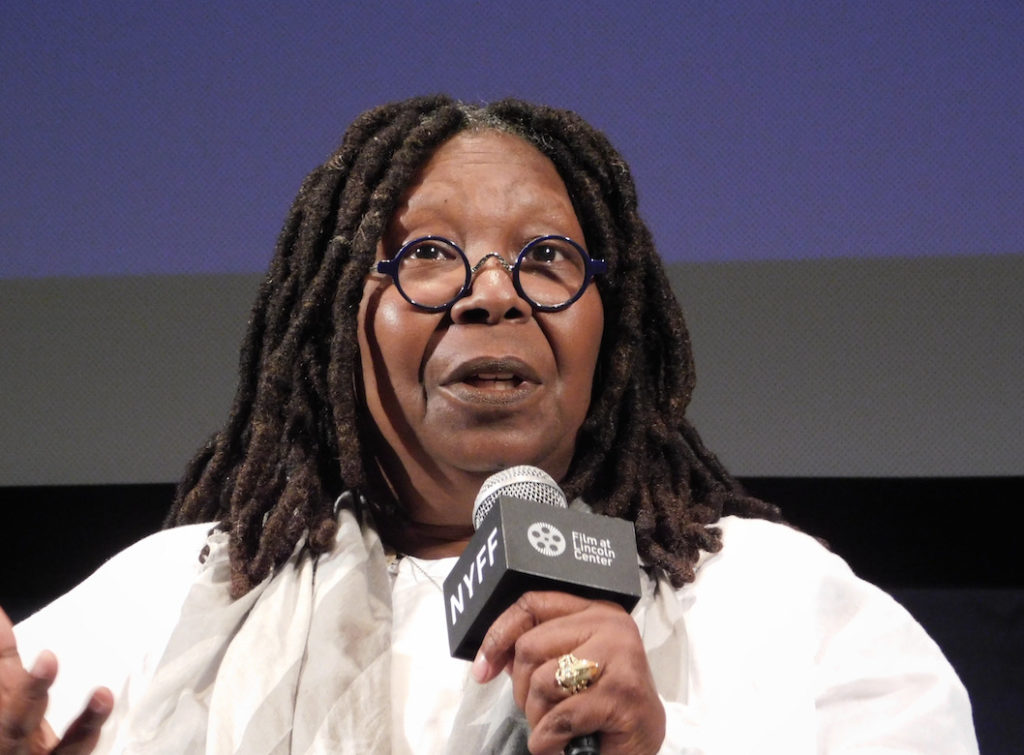

Q: Whoopi, why were you interested in taking this project on as a producer?

WG: This story’s been sitting there for 67 years. Everybody says they know the story. People throw the name out all the time — but they really don’t know anything about it.

For me, this is the same as “The Diary of Anne Frank.” This is truth, this is what happened, and we want you to know so that you can make up your mind, and say, “This systemic racism really affects all of us.”

Any time we can use information to make people smarter and recognize that they’re involved in all of this — that it starts here with Emmett and those hateful fingers of racism and sexism and all the other “isms.” They all come from here [indicating the audience] because this is what it looks like — this is what it does. It allows people to come to your house, take your family and do whatever they want to.

Gay folks get this movie, straight folks get it, black people get it, white people get it, women get it. It’s a movie for everybody. That’s why I wanted to be a part of it.

Also, [there’s] Fred and Barbara. I’ve worked with [them] before. They don’t do crap — and I’ve done some crap in my career. So, I’d like to be associated with non-crap. That’s the other reason I took it on, as much for myself as for anyone else.

Q: Chinonye, could you elaborate on knowing that you wanted to make Mamie Till Mobley the center of this story when they approached you?

CC: Without Mamie, the world — we — would not know who was Emmett Till. She’s the heartbeat of this story and should be [at its] center. Black women are so often erased from stories like this. We’re so often erased from history, the present and everything in between. That was another reason why I was so adamant about centering the story around this incredible black woman. By humanizing her and really showing her multi-dimensionality in all of the aspects of her life, this [film] really portrays her as more than just a grieving mother.

Whoopi was saying that there are a lot of people who think they know the story but have no idea. Part of what most of us don’t know is the journey that Mamie went on after Emmett was lynched, and all the intentional strategic things that she did, while also evolving in her own activist consciousness as well. I thought that was such a fascinating and interesting story that I wanted to tell it.

Q: Can you elaborate on [the idea of] not showing violence against black bodies onscreen? One of the most impressive things about this film is the way you filtered that. One of the points of Mamie Till Mobley’s activism was to force people to look at the hard truth of the violence that was done to her son.

WG: What you needed to see was the relationship. You knew what was happening. What you needed to hear was the sound. You knew what was happening, you didn’t need to see it. But you needed to understand what was done and why Mrs Mobley made the choice that she made.

Our hope was always that we would find somebody who understood the small things that this movie needed to have and respect that it needed to pay attention to the audience. [And show] the respect that the actors needed to pay to each other.

[Chinonye] understood that. So in discussing what we wanted to see and really didn’t want to see — we always knew it was going to be a mother-son story, because it had to be. Otherwise it’s just another, “Oh, I’ve seen this before.” But you haven’t seen this. When Chinonye says,“Here are the things I want to make sure we do,” we had made up our minds as soon as she said them. We knew we had found somebody who would pay attention to the little details that were necessary.

When you watch it, when you think of black people in the South, and these shacks, you see that. But you don’t think of Chicago in 1955, in a young man’s bedroom. It’s his bedroom, it looks like a room of any 14-year-old kid. It’s not toe-up, it’s not toe-down, it doesn’t need to tell you where to go. You follow the path that she has set forth for you to see these people as a family. They are ordinary people who have been thrust into extraordinary times. That’s what we needed you to see.

You know, a lot of people are scared of this movie. We know that. Keith and I know that. It’s taken forever to get this done. So I’m thanking you because I’m appreciative — it means people do want to see it. People do appreciate it. And love it.

Thank you [to Keith] because without Keith, we would have no idea of the lightness of Emmett. We wouldn’t have any idea of the beauty of his mother. We wouldn’t know without of Keith going in and digging that up. Usually in movies this is the periphery. But [Chinonye] made it the heart, and therefore the heartbeat for you all.

Q: It’s an extra level of responsibility to take on the personality of a real person. From watching Keith’s documentary, there’s a variety of material that you had to work with. Danielle, you had a lot of footage that you could look at for the real Mamie. Could each of you could talk about how you honored the people you were playing when you made the parts your own?

SPT: I played Gene Mobley, and for me, it was about how do I do this in such a way where Gene’s family, his loved ones, and the people who knew him, would feel respected when they saw the film. My main concern was that the people who actually knew him would not feel like he was done any disservice. That was very important to me.

A huge part in doing that was talking for hours to Mr Beauchamp, who knew Gene personally. He spent many hours and years with him and with Mamie, and saw them as a couple. That really helped me get a sense of, this is my road into doing exactly what I was hoping to do, which was to not do a disservice to the man and the relationship.

JT: I played Moses Wright. For me, the general thing was how do I play this ordinary man, a wonderful man, who was thrust into an extraordinary situation? What was that burden, and what were the feelings [he had]? I felt that I was given a lot of information as it related to my character. There is footage of him that I was able to find on YouTube, and there were the FBI transcripts of the trial itself, which was word-for-word, letter-by-letter testimony.

I also had some books. There was a wonderful book that was written by Simeon Wright [“Simeon’s Story: An Eyewitness Account of the Kidnaping of Emmett Till”], that’s about the family and Moses, his wife, their children, and about the event itself in its entirety. There’s also a lovely book by Mamie Till Mobley [”Death of Innocence”]. It’s a remarkable book and incredibly written. It gives you a wonderful account of her love for her son.

I had all the information that was given to us as resources. I was trying to do justice to a character, an individual, a real person who [had] this horrible thing happen to him and his family and loved ones. Was there any redemption? Was there a way to hopefully make things right? Which then, hopefully for my character, happens when we get to the trial scene and what my character actually decides to do, which no black man at that time had done something like that without losing their life.

So it was really trying to follow a track of an individual thrust into an extraordinary situation and trying to come out of that in the seeking of redemption.

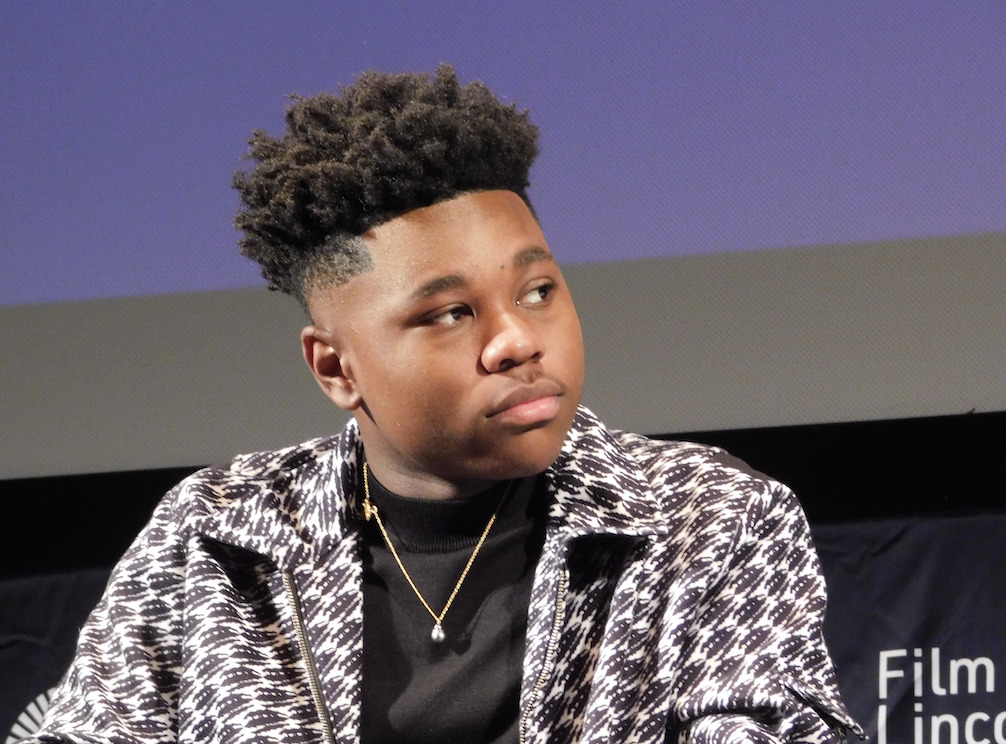

JH: I play Emmett Till. A lot of what we know about him are things that you can read or that you can see. But thanks to the guidance from these beautiful people [around] me, I got to learn a lot. One of the things about Emmett is that we see him as somebody in history who was at a pivotal moment. But you never really think about how he was — just a 14-year-old kid. He was regular. He may have liked to play video games or wanted to go to the moon — who knows? But it’s that innocence and that purity of heart and love that I wanted to desperately to embody. I’m showing you that he was just like anybody else who wanted to have fun and be curious.

So taking the personality traits that I learned about and that were shared with me, I put that into my performance, showing you what a human being, what a child and a black boy who loved his mother, that’s who Emmett Till was.

WG: You nailed it. I’ve been a grandmother since I was 33. I know a lot about being a grandmother, and I say that because grandmothers do stuff to mothers, their children, that are annoying. They say, “Let him go, he’s just going to see his family. What’s the problem?”

I’ve done that to my daughter, often. But the outcome was not the same. So I understood that. And for me, I was just glad to be here, because I hadn’t intended to do it. And they said, “No no, we want you to do that scene.” I said, “Are you sure? Because, you know, I’m iffy with a lot of people.” They said, “Shut up and be here when you’re supposed to.” So that’s what I did. Sick and lame, but I got there.

So it was a marvel to watch everyone, because I haven’t been living this material as long as Keith has. But I’ve been living with it for a long time. To see Emmett come alive, it was a marvel. So I’m gonna slip over here — because this [indicates Danielle] was the other marvel. You don’t get to see it often, but when you do, you recognize it. And you are incandescent as Mamie.

When you’re on set, you’re like, “Oh, my leg, I’ve got a cramp in my leg” and, “what’re you doing for such, you gonna eat? Yeah, I’m gonna eat” and then you hear “Action!” and you’re in it. But then when you see it — you took my breath away. I can’t stop saying it: you’re spectacular, a revelation.

[applause]

DD: This is one of those experiences where you know that you have an extreme amount of weight that you have to bear. There’s no other way to engage it. Chinonye and I had good long talks.

I’ve known Mamie and Emmett Till’s story since I was a kid in elementary school. My mother was born in 1955. It’s a year that rang for me a long time since I’d known it. We did the deep dive in all the ways — academically, reading a number of theses, and Mamie’s memoir served as a bible.

Poetry, music, the archival footage, photos — all those things. They continued to swirl daily, the months building up to production, all through production. These things have stayed with me the entire time. They still live in my phone, my mind, and life. In our lives, right? It’s not one of those things you can easily dispense with. We’re not allowed. In a way, we’re not allowed. I guess that’s why they’re scared, right? And we should be and confront it nonetheless. So that’s my experience, building and living with it.

Q: What conversations did you have about showing the aftermath of violence done to Emmett Till’s body?

CC: Well, the question wasn’t really whether or not to show the body, it was really how to do it. My decision to show the body onscreen was an extension of Mamie’s decision that she made in 1955. In order to honor her and the decisions she made, that was so critical to us in the civil rights movement and her story. We had to.

But as to how to do it, I approached it in a way where, when we’re first in the funeral home, the body is obstructed and we’re just with Mamie, and we stay in her emotional perspective. Because what that scene is about is more of us understanding what Mamie’s emotional processing is as she is seeing the body for the first time.

And then, when we really see a clear view of Emmett’s face and body, it’s with the large crowd in the church, and I wanted to replicate the experience of the world witnessing what happened to Mamie’s son Emmett in a very visual and cinematic way. I knew that the best way to do it was to do it sparingly yet effectively. So the moment that I decide that in the story where we need to see the body, I knew it was probably only going to be once. But it needed to really have a narrative and emotional impact. And then we’re done.

WG: The other thing she did was allowed us to know Emmett’s body the way his mom was getting to know it. She says in the courtroom, “I know my son.” Once you see her and she’s touching each place, you stop being [gasps!] by it, and you realize that you’re seeing a mother touching her son. It allows you to be part of it. I thought that was a wonderful way to go about it. It was magnificent.

DD: I concur. It’s a humanizing of his body as opposed to associating and affiliating it only with the violence enacted upon it. Comparatively, we look at what happens to black people’s bodies today, at the violence enacted on them, that’s not done with critical care. That’s [someone] trying to get someone in a “gotcha” moment. That’s trying to do something defensively, as opposed to this is critical care for the wellness of the narrative and the story of his life, and critical care for the aftermath of what happened to black people as a result of her showing it to everyone.

CC: Humanizing, not objectifying.

Q: How did you approach the use of sound and music? How important were they to the narrative?

CC: When I tell you I love the language of cinema, that absolutely includes sound and music, and the relationship that they have to picture. Abel Korzeniowski [is] the composer of “Till” — a brilliant composer in general. I am a film score junkie, and he was on my wish list of composers to get for this film. We talked extensively for many many many months about the sounds and music of the film.

We talked about emotional subtext. I love a score that does more than just underline what we see on screen. Abel and I had endless conversations, we literally went scene by scene and talked about whose scene is it, and what’s going on emotionally? How do we underscore that?

A great example of that was when we were talking about a scene where Mamie is seeing Emmett’s body for the first time. Visually, it’s a painful, sad, tender, humanizing moment. This is one of the things Danielle and I talked about when we were discussing the scene, because she actually did it as part of our director session and call-back.

Part of the subtext that Abel and I talked about was the rage and anger that’s building up inside her which leads to her make the decision by the end of the scene. Abel scored the film highlighting that emotional subtext because then that’s going to complement what we see visually. We also used the language of horror when talking about certain moments. When she has that intangible knowing that is inside her, especially when she sees Emmett off and when she gets the news that his body was found, that’s when I used the zolly shot. That was something that I’ve seen used effectively in horror films: the horror of that moment.

The soundscape that was discussed was [that] we don’t want it to be like a cheesy, horror-sounding, psycho movie. But how do we communicate that horror in a sophisticated way that still favors Mamie’s emotional moment — by the use of silence. I believe silence is also as important to the soundscape and the music. I was very intentional about those moments of silence that can be juxtaposed against those louder moments. So when we see Mamie in the train station receiving Emmett’s body in that box, the music crescendos and it’s almost deafening. Then we cut to this chilling silence to respect the moment that’s going on, to respect Mamie’s moment with her son.

I had a field day thinking about this stuff, silence, soundscapes and music. But all of it is an extension of the storytelling, the emotional beats and subtexts of the characters within the scenes.

Q: Could you clarify whose picture is in Emmett’s wallet that he shows to the woman who will ultimately betray him?

CC: There’s a shot of the wallet and Emmett holding it up in that scene. It’s Hedy Lamar. We see it in the store, in his bedroom, and then we see a shot of it clearly in that scene. We see that and then we cut to the medium of Carolyn.

Q: How did you approach filling in period details of the historical era you were recreating to achieve the tone you were looking for?

CC: I first need to acknowledge some department heads: costume designer Marci Rodgers, production designer Curt Beach and cinematographer Bobby Bukowski.

The first set of conversations I had with Marci, Curt and Bobby was that I wanted a vibrant color palette. I want the clothes, production design and lighting to reflect the vibrancy, beauty and richness that is black people, black communities and black spaces. So that informs the bright wardrobe pieces. We used wallpaper that was fitting for the time period — we just ramped it up a bit. That was also what Bobby did with the lighting. That was integral.

In terms of cinematography, Bobby and I had a lot of conversations about framing and compositional choices, because what’s out of the frame is just as important as what’s in the frame. Whose gaze are we centering, and who are we intentionally excluding?

A clear example of that is the testimony scene. Whenever I talk about planning an aspect of the film with any department head, especially with my cinematographer, all of the creative decisions that we discussed had to be rooted in the storytelling. When we were getting ready to shoot the scene of Mamie’s testimony, Bobby and I had eight or nine different setups that we thought were going to communicate the complexity of Mamie’s emotional moments throughout that extraordinary performance. The first setup was what we saw in the film. After that first take, I was like, “damn.” I think everybody was. Then with the second take, Bobby and I looked at each other [and went,] “I think we’re good. I don’t think we need to do anything else.”

So when I talk about framing and compositional choices, I have to make some adjustments because as Danielle was channelling, transforming, I knew, in order to make the scene work as a one-er, I had to adjust the framing and composition, and be clear to suggest the world beyond the frame. Bringing in the hands of the lawyer, the rings, and the photos, we used rack-focusing from the jury to Mamie.

I needed to make sure that we were clear about the spatial relationships and about who was speaking to her. But we didn’t need anything beyond that. The narrative and emotional focus is right there. So we had eight or nine other shots planned, but in being present in this extraordinary moment that we all got to witness in Danielle’s performance, it became clear that there were more ways to communicate that kind of emotional subtext that we wanted.

Q: This story took place in another century. How relevant is this film today?

WG: You know how relevant this film is today. It’s more relevant every day. It ties in more and more people, because, again, what you see is the culmination of everything that we are all living right now. And it’s not just us anymore.

So it’s really important that everybody recognizes what institutional racism looks like. We are slipping further and further and further. Unless we can show people what this actually means — in terms of people walking in your house because they don’t care who you are, and you don’t matter to them as human beings — we may be facing this again if we’re not careful.

It’s imperative for everybody to say, “I don’t think we want to do this anymore.” We recognize that we didn’t like it when we saw Trayvon Martin lose his life. We recognize that we didn’t like it when we saw Breanna Taylor lose her life. We knew that we didn’t like it when we saw George Floyd lose his life.

And now we’ve taken you to Point A and say, “From here, spreads all of this. We can stop it if we choose to.” That’s what this is about. This is about all of us. Emmett Till is all your brothers and sisters — your husbands, boyfriends, lovers. That’s who Emmett Till is.

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.