Synopsis : Set in Japan in the year 1600, Lord Yoshii Toranaga is fighting for his life as his enemies on the Council of Regents unite against him, when a mysterious European ship is found marooned in a nearby fishing village.

Creators: Rachel Kondo, Justin Marks

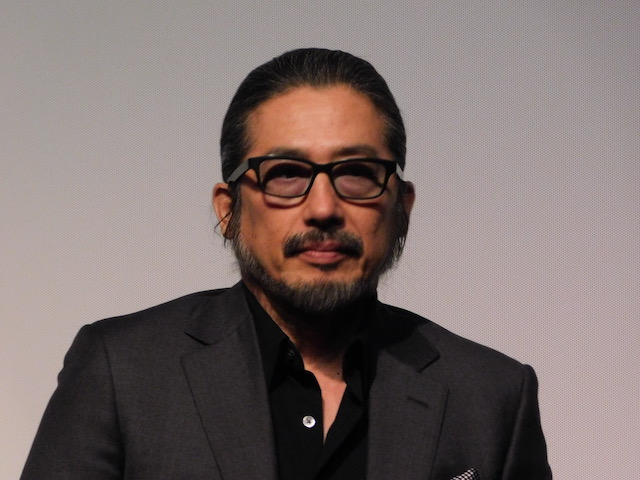

Starring: Hiroyuki Sanada, Cosmo Jarvis, Anna Sawi, Tadanobu Asano, Hiroto Kanai

TV Network: Hulu

Premiere Date: Feb 27, 2024

Genre: Adventure

Executive producers: Rachel Kondo, Justin Marks, Edward L. McDonnall

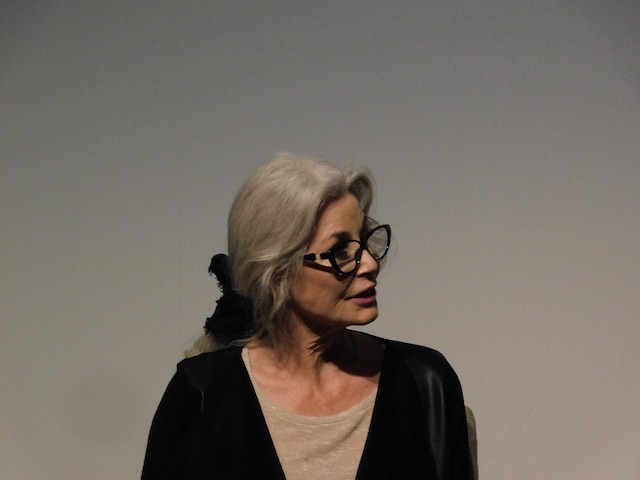

Press Conference with Actor/Producer Hiroyuki Sanada, Co-Creator Rachel Kondo, Justin Marks, Executive Producer Michaela Clavell, Producer Eriko Miyagawa

Q : The original show that was a big hit that won lots of critical praise so many years ago. What was the significant change, the main difference in the show that you wanted to show the world?

MICHAELA CLAVELL: I’m the estate. I worked with my father(James Clavell, Writer/Producer of the Original “Shogun”(1980)) for 15 years before he passed away. So, many people came to us wanting to remake it. And we were very careful about who we chose to go with. And FX was very generous with allowing us to participate and to some degree, to be able to keep the quality of the book.

And the reason that we went with them and at this time is really because the technology had come so far. And the viewer audience on cable is quite different to the late 70s on network TV, which was much more limited in what you could do and how really true to the book you could be.

Because I believe what Rachel and Justin, Hiro, Eriko did is very true to the book, and the darkness of it, the lightness of it, the Japanese-ness of it, the authenticity of it, and I think we were able to bring it to the screen in an authentic way that my father would have been so proud of. Because he was very careful with how he wrote and the detail he gave in his books that, it was authentic to the times. And yeah, we were very proud to be able to do this.

Q : Justin and Rachel, do you want to add to that?

JUSTIN MARKS: For Rachel and I, reading it from a modern point of view today, we really saw an opportunity in a story like this to go back to the book and use it to reinvent, in some ways, how we have collectively as a culture and in our country in the United States, told stories like this.

When I first read the book, it’s a wonderful story. You really are in the hands of a master storyteller. And in early conversations with FX, what we said — our approach was, we wanted to tell this exact story, with one big exception for modern day, which is we wanted to subvert the gaze of the storytelling as much as humanly possible.

It began in the writers’ room, working together, looking to the text to enhance the world-building, which really was just a matter of going to the book. Because so much of the research was there, and then it extended into the production process.

And this enormous army that Eriko and Hiro-san, you know, commanded every day. You know, a truly an intersectional crew of about 3,000 that we used in Canada to put this together.

So, you know, we think that the chance was for us to tell one of these stories of cultures meeting each other was, it — it was kind of time to reevaluate the way in which we tell these stories.

HIROYUKI SANADA: Yeah. Of course, you know the original one was great. And then, I respect the novel. It’s a great script, so I was so happy about that. I brought the novel on set every day. I read the script and novel back and forth Like a bible, I was holding it the whole entire shooting.

Of course, like Michela said, we had new technology, and also try to make this believable, we have to make this rather authentic. So, authenticity is very important. That’s why we hire the Japanese crew, who has a long experience for the samurai drama. So wig, costume, props, everything. And then, most importantly, master of gesture called Shosa- how to walk, how to sit, how to kill, everything. We have good coaches on set. So, we try to do our best to make authentic.

Q : Speaking of authentic, what’s amazing about this, actually, it’s not just originality, but also the authenticity of the casting. You guys have really top-notch Japanese actors. So, talk about casting process of casting as well.

JUSTIN MARKS: I’m glad you brought that up, and thank you because we see one of our cast also in the audience today. Ako-san [“Daiyon” / “Lady Iyo”] is here.

You know, casting this show was truly, for me, one of the greatest pleasures of my career. We had the opportunity to do something, we were given this opportunity by FX that they were allowing us to tell this story in Japanese, which meant that the caliber of cast that we could get was straight from Japan. it wasn’t a limitation if they couldn’t speak English or couldn’t perform in English. We could really go for faces that we in the United States have never seen before.

And we worked with Kei Kawamura [Japan casting director] out of Tokyo to really kind of, in a very bespoke fashion go through it role by role, I think, for every single part, with the exception of “Toranaga,” who was there from the very beginning.

There was such a depth that it was just a question of sort of saying, “okay, we could put him here, and then we could take him who he’s not going to work there, well, we’re going to put him here. There were so many great actors at our disposal. It extended beyond just choosing the right person for the part. It allowed for us to get actors to perform in such a way that they could really infuse who they were into the part and to make these roles come alive in maybe a different way than we originally expected.

Because you live with this book for so long, but I think specifically the character of “Buntaro,” Shinnosuke Abe plays him and I think we had ideas in our head and also – Emily, are you here? (pointing into audience) Emily Yoshida, one of our writers, is here as well. And I was thinking just how different “Buntaro” was in the writers’ room compared to when Shin began to embody that character and change who he was.

RACHEL KONDO: “Ishido” — the other character who while reading the book, we had certain ideas in our heads, possibly slightly older actor — more staid, more stoic. And I think it was your idea to skew a little younger to do more unexpected casting.

JUSTIN MARKS: It was Hiro-san’s idea.

RACHEL KONDO: Oh, pardon me.

JUSTIN MARKS: This was such a big part of it. So, many actors who are part of the process early on and there’s this, you know, tradition that we sometimes do, “Okay, well, now you’re a producer on the show, too. Great.” Then it’s a credit that everyone feels good about, and then that’s the last we see of it. This was not the case with Hiro-san on this show.

From the early casting process, every role was vetted with Hiro-san to sort of talk it through. And I remember in the case of “Ishido” specifically, you were saying, you know, just you’re looking for the right foil, the right rival.

But then, I mean, it just extended to — on set, we would be shooting scenes where Hiro’s wearing full armor on a horse or a step ladder, pretending to be a horse, for coverage, and then finish, you know, the coverage in his direction, and turn around, and we’d be sitting at the monitors, and then all of the sudden, there’s this armored “Toranaga” sitting next to us at video village monitoring every detail of the frame.

And you don’t get that from any other actor who has this. This is truly a producer we’re sitting with, and the show wouldn’t be what it was without it. Every single member of the cast joined this show in order to work with the man you see here today.

HIROYUKI SANADA: I’m so happy. And then, you know, all Japanese roles played by Japanese. That’s necessary. And then they allowed us to do that, so thank you.

Q : Can you tell me about the score and [composer]Atticus Ross and how he was brought aboard, and how that all transpired?

JUSTIN MARKS: Yeah. We’re so proud of what Atticus, and Leo [composer Leopold Ross], and [composer] Nick Chuba came up with for this show. You know, the early conversations — and it speaks to the philosophy how we wanted to make this show.

You know, there were – I grew up on Japanese cinema as a fan. When it comes with Kurosawa – obviously, he looms large in our mind and, you know, early on that we decided to try to do a style of filmmaking that was imitative of a culture that would be speaking – or for me, I didn’t belong to, felt truly false.

And when it came to the score, the early conversation was that I don’t want this to sound like we’re standing in the lobby of a Japanese restaurant, you know, that we’re trying to pretend that this is something else, that we needed to go deeper outside the culture to a space of psychology for these characters.

And what they did is they went to a Tokyo-based ensemble who used very specific instruments, many we had never heard before, and then we began to experiment with it in an electronic and psychological space. And we thought that was very exciting. It didn’t come without, you know, moments of kind of awakening.

As Hiro-san mentioned, we had such a huge Japanese crew working, you know, in key roles throughout this, and Aika — I’m reminded, Aika Miyake, one of our editors pointed out on the mix stage – do you remember that day when we were looking at – it was Episode 1, and it was the ride in, and we had one of those horns that they were using Aika identified as a — it was for weddings, right?

It was a, you know, kind of a wedding, horn was how she associated it. And it was being used as in sort of “Toranaga” coming into Osaka castle. And here it is, and she just said it’s like to her ears having grown up in Japan, it’s like playing like “happy birthday” to you or something in the middle of this. It just sounds so strange. And it was just such a nice gut check to sort of be like, okay, well, let’s just pull it. Let’s change the instrumentation of this. Because, again, it has to work on all sides. But again, it was just so great, the experimentation and kind of getting to the very unusual sonic space.

Q : I just wanted to ask you about your approach in the writers’ room because, as you mentioned, it’s a culture that you don’t belong to and how this might have been different from other projects, not just for story but character and language, what the approach in the writers room was for that?

RACHEL KONDO: I mean, it probably started way before for Justin and I were involved, way before you and me were even born.

MICHAELA CLAVELL: I had brown hair when this took place.

(Laughter.)

RACHEL KONDO: But when we came on, Justin had some misgivings about approaching the subject matter. And I felt invigorated. Wow, what a great opportunity for me, a person of Japanese heritage to step in and to, I don’t know, command attention and have something to say.

And really, the process that we went through initially, I think, kind of bled into our writers’ room, which is that there was a lot of humbling that had to happen. And we had to kind of understand that, because I’m a person of Japanese heritage, I actually didn’t have anything more to add than even somebody who didn’t have that heritage because my heritage is, I’m Japanese-American from Hawaii.

So this is all many degrees removed, and I’m not “Japanese.” And so, it was a like a zeroing out of who we were to be able to have the openness and the curiosity and the ability to absorb from our real Japanese counterparts and people who had expert knowledge about all — all that we were trying to express.

So and I think the Japanese —The writers’ room, we assembled a fabulous team of predominantly Japanese, Japanese-American, or excuse me, Asian-American writers, all Japanese and Chinese-American, and predominantly women.

And something that we had to learn is, a lot of us were also half Asian. So there’s a lot of it was a lesson for us to understand to find the space in between two worlds was actually the asset that we brought to the table. And so, there were a lot of lessons to learn.

JUSTIN MARKS: We also had the benefit, Pandemic, of having this extra year of sitting on our hands kind of waiting to find out when we get could shoot a show again.

And what it allowed us to do is actually sit on the scripts that we had written with the room, these ten episodes, and work with and individually reach out to Japanese producers to kind of get — I think when we started and what Rachel talked about was this process of humbling.

Everyone on this crew on this show, including ourselves in the beginning, comes into it saying, look, we’re going to do our thing, and we have a way of doing things, and we’re sensitive people, and we want to listen and whatnot.

And then you always do this thing where you send it to — you know, Eriko has seen this a billion times over the course of the last couple of years we’ve been doing this. You send it to your Japanese counterparts partners on the project, and what you’re really looking for –you say “thoughts, please.” But what you’re really looking for is approval.

And we realized early on — and this was working with Mako Kamitsuna, one of our producers, who’s a great writer and editor and was reading every script with us. And we were not getting approval.

Mako held fast because she said this is not something — I can’t even give you notes on this line because a Japanese character from this period wouldn’t even think this way. You know, this isn’t how it’s done. And this is how it would be done. And so we began to really workshop it over the course of a year to change that.

And which was a very — for a writer, a very humbling process. And you quickly find that all the tools that you have mean nothing. That you can’t go to partners looking for approval. You have to go to partners looking for inspiration in partnership with each other.

And that was just our great department heads learning this time and time again. And I can think of Carlos Rosario, our costume designer, the beautiful work you did was because he worked in tandem with our Japanese team. He didn’t just do this work and hand it over and say is it good? He really was there from the get-go. And you know. It shows.

HIROYUKI SANADA: And the Japanese script, Justin sent to me every episode. The first translation was done, and then I take notes, and translation and the script is totally different. So, I take notes and make changes, send back, and then back and forth.

And especially with the dialogue, it’s difficult for the writer as well. So, yeah, we discussed about how to say with the actors too, and especially Ako-san, you know, “with my character in this situation, I want to say it this way.” You know, and that’s so helpful for the show, and then they are so flexible for that. So, we created together with whole cast and crew. I’m so happy about that.

RACHEL KONDO: I think you touched upon the process that you mentioned, the language, right? The process that we went through, sort of the machine that had to be built in order to initially write it in English. Everybody in the writer’s room that spoke English as our primary language. From there, it was, we went through cultural translation. And then, it was sent to a team in Tokyo to translate it. Then it went to a playwright, a Japanese playwright, to kind of add her flair to it, and then it was spoken by our amazing actors, who added their own slight adjustments or their own.

ERIKO MIYAGAWA: Inflections.

RACHEL KONDO: Yeah, inflections, their flair. And then, it finally came back to us in post, which I think Eriko, thank you for all of your months and months that you devoted. But from there, I don’t know if you wanted to share what the three of us had to — with the subtitling.

ERIKO MIYAGAWA: Yeah. So, I had all the dialogues transcribed. And then I translated them back to English. You know, just so Justin and Rachel can really understand that there has been an inversion of what exactly is being said in Japan.

Because English and Japanese are obviously very different languages that — and you know, the point is like the intention has to come through. And to deliver the same intention, what might be said in English and Japanese could be very different.

So, we have this kind of process of re-checking every single dialogue and for them to understand what is being said so they can make the final decision, how to best incorporate that into the subtitles so that Japanese-speaking — Japanese audience can have the same experience.

JUSTIN MARKS: It was really — the words that you see on screen in the subtitling were not the words that were originally written in, I would say, 80 percent of the cases. They went through this just elaborate game of telephone to find their way back to the state that they’re in. And we’re really proud of that there are — because there are lines on screen that we had no part in writing.

RACHEL KONDO: Couldn’t have thought it up on our own. I mean, it was real learning curve and a beautiful lesson to see — to watch it all go through the machine and come back in such a — such an improved, more poetic way. Oh, you would like me to give you the example.

So, in Episode 1, there’s the scene towards the end in which “Toranaga” is speaking with “Mariko-sama,” and she is saying — or he’s asking her if her faith would conflict with her service to him. And her response is, “if I were just Christian, then, yes, it would.” And the line following that is, “but I am more than one thing.” That was what we had originally written in the writers’ room, which we thought, ooh, was so good.

But then it goes in the machine through all of our various contributions, and it comes back to us, having them spoken in Japanese, having been re-translated back to English as, “if I were just Christian, yes, but I have more than one heart.” And I mean, how much more powerful is that? And none of us could have come up with that, so.

Q : What was the name of the Japanese playwright that helped translate the script?

ERIKO MIYAGAWA: Kyoko Moriwaki. She’s based in Kyoto. She’s a wonderful writer.

Q : How long did this process take, translating from writing the script, translating it into Japanese, re-translating it to English? Like, roughly how long?

RACHEL KONDO: We’re still in it.

(Laughter.)

JUSTIN MARKS: Yeah, no. I mean, what you’re describing is what I’m just seeing Eriko doing at video village every single day with the sides, just sort of like going from her phone to her laptop, ’cause, the nature of production with me also – is that there are a lot of rewrites and things that we adjust. And there’s a large train that has to follow that rewrite when it goes into translation. And very often, Eriko was doing on the fly on the day of just kind of cold reading all the notes.

So, I would say, five years because that was how long we’ve been doing it, but in actuality, even the process would be — I don’t remember the gun that was held to my head in terms of — was it this is how far I was. Was it three weeks, I think, was really the…

ERIKO MIYAGAWA: Three weeks was how long it would take to translate the entire script…like, rushed. Again, the polish with Kyoko, the polish with Hiro-san, and the polish with the actors. And then, inspiration tends to come about when we’re shooting. And oftentimes Justin may say, is it okay if we do things like this? And then maybe consider it. So it was — just always, it kept moving.

RACHEL KONDO: I think we would be remiss to also not mention that none of this existed, obviously, before the show, and so I think we were all learning what had to happen. Like we didn’t go into it thinking this would be a great way to approach.

JUSTIN MARKS: Yeah, that’s a really good point. Because Hiro-san was the one who brought it up when we first — early, long before we were shooting, you know, when we had the scripts translated the first, like, three times into Japanese, who said that this isn’t really performable. And we had to figure out another way to do that. And, you know, it was — was it Hiro-san, or was it Eriko? Who was it that — who found the playwright, specifically? Oh, you know, was it Elephante [translation company] that reached out to her?

ERIKO MIYAGAWA: I think it was Elephante.

JUSTIN MARKS: But yeah, it was kind of a lot of this show was not reinventing the wheel. It was like inventing what a wheel is.

ERIKO MIYAGAWA: Not to mention the polishing — making it to period language. Because back then, Japanese was quite different. And, of course, if actors speak exactly the way it was spoken, the audience wouldn’t understand what’s being said. So, the art was in just finding the right balance to make sure that it feels authentic, it feels period, it feels the time, but at the same time, making sure it’s understandable to a Japanese audience.

MICHAELA CLAVELL: Hiro, I think you may have had some experience with that — the difference between the older Japanese and the modern Japanese.

HIROYUKI SANADA: Yes.

MICHAELA CLAVELL: Many, many years.

HIROYUKI SANADA: Yeah, since I was a kid, I’ve done a lot of samurai movies, something like that. So what might be a traditional way to say coming out of my mouth even reading the monologue. So we tried to make a good balance. If it’s too traditional, some young audience cannot understand, but we don’t want to put this subtitle Japanese to Japanese, right? (Laughter.)

So, we took the balance. Easy to understand but flavor of traditional way. So, we took a good balance with our team and actors. So, yeah, it was an interesting process, and then very important, and that never happen like this, you know, deep communication from the beginning to the end. So, I believe this is a dream East-meets-West project. I’m so happy.

Q : The subtitling, I was a little curious why none of the English words were subtitled. To me, it’s like something a little bit uncentering and sort of the assumption of who is watching this. And so I’m curious about the position that you have of any of the English kind of speakers be subtitled, some of whom are quite accented. So, sometimes it can be a little bit difficult to understand what they’re saying even if you understand English.

JUSTIN MARKS: Difficult to understand, like the Portuguese actors speaking English?

Q : Yeah, yeah. So, I was curious about just why none of that was also subtitled the majority of the show.

JUSTIN MARKS: I mean, this is being shown in the United States, and so we subtitled it in English, but it’s interesting that you mentioned that it’s hard to parse even some of the English as an English speaker. Because I’m thinking about “Rodrigues” specifically sometimes, who could be standing right here and in that accent as he was doing, and I wonder.

But no, I mean — when this the shows, for example, in Japan, we’d be watching this inverted. Or they’d be watching this inverted. So, the choice here is we’ve decided that English is our lingua franca for Portuguese. And for our gaze here in the United States, it’s also being done that way.

We did look at a version that we screened for the cast and crew when they’re wrapping at the end in Vancouver. We wanted to show everyone a couple of scenes that had been put together. And when we’re there in Vancouver with our cast and crew — it’s a very bilingual set. You hear in safety meetings in English and Japanese as a matter of the process because it just feels that it’s good manners. And when we wanted to show scenes, we decided to subtitle both as we’re striving in English and Japanese so that our cast could watch along with it.

And I have to be honest, it was actually turning on closed captioning. There was a tonnage that started to happen. So, by doing it in this way for an English-speaking audience, it seemed to just simplify it for us. But it’s — it’s an interesting point about the accents that I haven’t really considered.

RACHEL KONDO: Back to the drawing board.

(Laughter.)

Q : I was wondering if you could elaborate more on the set design and costume in a specific way how you guys got it to look so good.

ERIKO MIYAGAWA: So costumes, Carlos [Rosario], a wonderful French designer, he had Kazuko Kurosawa, who is a very established costume designer in Japan. She’s daughter of Akira Kurosawa. So, she was an advisor for Carlos. So at beginning, they had conversations, and she had sort of Akira Kurosawa’s right-hand man in Japan to, you know, go through the construction of the kimono and our source to the right type of textiles from Japan.

So, Carlos had a lot of direct support creatively and practically from Japan. And you know, likewise, Helen Jarvis, who was a production designer. She worked with Kyoko Heya who’s also a veteran, you know, production designer in Japan.

Funny story is that she worked as an assistant on the original Shōgun when it was shot in Japan. Yeah, so it was a full-circle moment for her. She was so excited to do this. So, you know, Helen would send her the design ideas and plans, and Kyoko will send back into the notes, and they would talk. And so, that was the process that — that kicked off the beginning.

JUSTIN MARKS: Also saying in terms of, you know, things we collectively learned beyond just design of these elements, I’m thinking about wardrobe. And you know we have — we’re in Vancouver. There’s not a lot of shootable day in the winter, so you’re always looking at your watch as we’re just preparing to get our first shot off. And sometimes we have 150 extras in any given scene, which — that’s a lot of people to put into costume. That’s a lot of nakazori(It’s for foot, not head) to put onto their heads — you know, the caps. That’s a lot of makeup to put on.

And you know, there were conversations early in prep with the studio about resources. We always had a healthy amount of resources, but you’re always forced to make choices at various times. And I remembered as a conversation about obi-tying, the belts, the kosode — and just kind of — there are YouTube video for that. We can all look at that, and we can all understand these things. Because, again, everyone’s sort of coming into it with their tools at the very beginning. Three days into production, we have tires coming out from Japan in armies because we just couldn’t get people up fast enough. And you know it speaks to — there are many values — the word inclusivity is an important one, and it’s — you know, there’s a — there’s a corporate component of that. You know, we all kind of understand what that means.

But I think there’s a creative component of it that we do this because it makes our art better. It makes our days go by faster. It makes our extras come out sooner to have the people who have done this for their entire careers out there working day in, day out.

And then over time, you know, as the Canadian crew was able to work with these Japanese professionals, you know they were able to learn and slowly but surely, things could evolve and then they got even faster.

But it was always this sort of really decision-making process that had to go into it. And Hiro-san, it was you who was like, no, “we really need them from Japan.” You were saying — I remember I was standing in New Hampshire months before we were out in Canada listening to you on the call about exactly that.

And then, we were in Canada, you know. So much of this feels like the very often — Eriko’s “Jim” from “The Office,” like looking at the camera or something in this way looks, like eventually they’re going to come this way. And then, sure enough, like, two weeks later, there we were. But you have to find your way to it, and we did.

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the series.