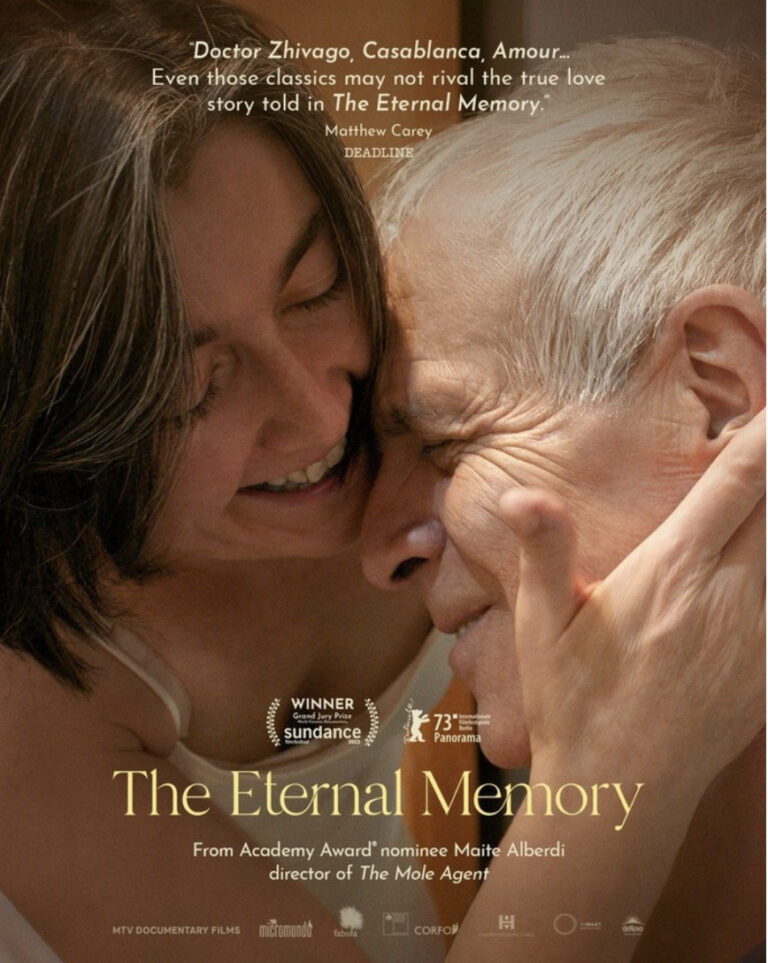

Director Maite Alberdi emotionally captured the hearts of audiences at Sundance 2020 with “The Mole Agent.” The film went on to garner an Oscar nomination and was shown to audiences around the globe. Now, she made her surprisingly well-made documentary, “The Eternal Memory,” which won the top prize for the World Cinema Documentary at this year’s Sundance.

Chilean TV journalist Augusto Góngora and Paulina Urrutia, an actor and former politician, who served as Minister of Culture, were married in 2016 and were together for 25 wonderful years. But in 2014, Augusto was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and his partner Paulina became his caretaker, which proved especially challenging when his symptoms began worsening during the pandemic. Director Alberdi documents a heartbreaking and heart-warming story by giving audiences an incredibly frank and intimate look into Paulina and Augusto’s lives.

Genre: Documentary

Original Language: Spanish

Director: Maite Alberdi

Producer: Maite Alberdi, Juan de Dios Larraín, Pablo Larraín, Rocío Jadue

Writer: Maire Alberdi

Release Date (Theaters): Limited

Runtime:

Distributor: MTV Documentary Films

Production Co: Inmaat Productions, Fabula, Micromundo Producciones, Chicken And Egg Pictures, UTA Independent Film Group

Exclusive Interview with Director Maite Alberdi

Q: How did you meet Augusto Góngora and Paulina Urrutia in the first place and how did you decide to tackle this project?

Malte Alberdi: I met them in a class that she asked me to do in a university that she works for. I was making my class and she was with him and he asked me questions. I knew that he had Alzheimer’s disease because he openly did an interview in a big magazine.

I was surprised to see how Paulina and all the people that work with her integrate him. I saw how in love they were and that was my first approach. I have never seen before a person with dementia that was not isolated from society. He was completely integrated and I saw them as a couple. So my first idea was [to ask] how this couple can continue being a couple and I wanted to make it a love story as well.

Q: You’ve been documenting them for almost four years. Some of this film shows very intimate moments that pass in time. As a filmmaker, what parameters did you set up to film them? Are there any boundaries that you’re concerned about?

Malte: We have been shooting for so many years. It was like a five-year process so the boundaries were constructed together, like trying to make them feel confident about speaking together and about which places they felt comfortable to shoot in and which ones were not so. Step by step, that confidence between us was developed.

Q: During COVID, you handed the camera to Paulina to record a very intimate moment in this film. You also have some archival footage from them. How did you construct the narrative of the whole film with the archival footage, the footage you shot and the actual film that Paulina shot during COVID?

Malte: During the COVID [pandemic], the lockdown was really long. At the beginning, I asked her to record, mostly for research material, to understand what was happening there until I came back. The lockdown took longer than expected. I was not thinking of giving instructions to Paulina as to what she had to do. It was completely intuitive for her to shoot what they were learning. I gave directions as to how to use the camera but she never learned really well how to use it. It was more that it was completely open and I’m very grateful for the [intrusion] of COVID. In the end, it helped us to have intimate scenes that I would have never had, even if I had all the access to them. I couldn’t have filmed all the moments that happened in the middle of the night.

Q: Alzheimer’s is irreversible. It’s a progressive brain disease that slowly impairs memory and thinking skills. It eventually results in a loss of the ability to perform even the simplest tasks of daily living. During your research, what things did you learn about Alzheimer’s disease that you applied to the filmmaking process for this film?

Malte: I have been shooting people with dementia for many years, but in this case, I realized that there are some things that the body never forgets and it remembers until the end such as the painful loss of a friend during the dictatorship. There were nights he spoke to Paulina and recognized her until the end. There were moments or nights when he got lost constantly. Yet, he recognized her. So it was a particular way to have an eternal memory — that’s why it’s the name of the film.

Q: Because of Augusto’s professional life as a journalist, he recalled some of the important moments of society in Chile. What were the things that you discovered about his career as a journalist that you found fascinating?

Malte: I find it fascinating that he was a man who was really concerned to show what was happening in the country. Nobody knew what was really happening because the media was held captive by the military so we only have that version. He and a group of friends risked their life to communicate. Then, with the return to democracy, he was concerned about bringing culture back to the audience and making a lot of cultural programs on public television. He was a guy who was concerned with constructing and preserving memory. So that’s why his career, to me, was important to the film in the end because it was completely related to the topic of the loss of memory of someone who constantly tried to preserve it.

Q: This is a film about memory and holding onto memories but at the same time, it’s also about living in a moment. What does it mean to you when your subjects are trying to cherish their memories and live in the moment at the same time?

Malte: It’s a film that promotes the present. I feel they are really connected with the moment that they are living in. But the only way to understand that moment and way of life, the moment is related to the past — with the past relationships and past personal history. How they approach the present is completely related to their relationships and the careers that they constructed before. You can’t understand the dimension of leaving the present without seeing the past. That’s why the film is not linear — it’s not edited in chronological order. It’s edited by associations.

Q: It was very heartbreaking to see how Augusto was left wondering during the COVID lockdown why all the friends and the family didn’t come to his house and visit. What went through your mind when you saw the footage that Paulina shot for the first time?

Malte: it was very heartbreaking because you cannot explain [to] him the lockdown. It was like I was living with a two-year-old son and couldn’t explain to him why he couldn’t go out. To show a woman who constantly is trying to bring him into the world, to work with him and to be socializing, that was a goal of the film. It was so clear that he lost his identity when he wasn’t socializing. It was heartbreaking to see how people with dementia need to be in society and not just with a caregiver. He’s very well cared for but he needs other [people].

Q: After you shot this film, what were the most important things that you learned from Paulina and Augusto?

Malte: I think that I can be with them until the end. They have the spirit of continuing as a couple until the end, to continue having good moments. Even if they were passing through a bad situation, there are people who don’t understand Alzheimer’s as a tragedy if they can be together. So I really see a new way of living and loving, a new way of being a couple — really understanding that they are two and not one.She’s helped him until the end to remember. That for me was a lesson and a gift.

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.