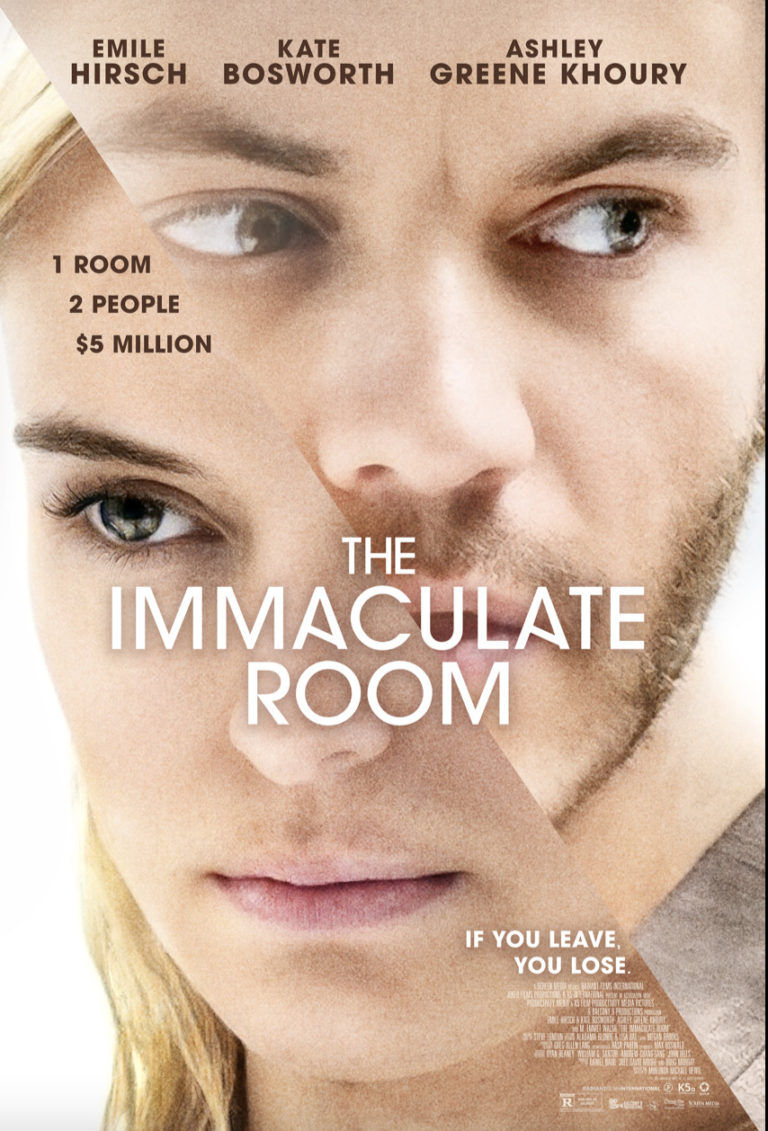

Synopsis : The Immaculate Room tells the story of Mike (Emile Hirsch) and Kate (Kate Bosworth), a seemingly perfect couple, join a psychological experiment to compete for 5 million dollars if they can last 50 days in a sleek, white room in complete isolation. No phones, no family — only the Voice of the Immaculate Room keeping them in check if they think of straying. But as the clock ticks down, the Room becomes more than it seems, putting them through cruel tests to break their resolve and resurfacing private demons which they may not survive.

Q: The concept is like a reality game show, but underneath the storyline it has great observations about human behavior. How did this story come about?

MMD: I’m fascinated by human behavior and the mind. There’s a saying that you can’t solve a problem until you first acknowledge that a problem exists. Most of us spend so much time being constantly distracted, and because we’re distracted we never deal with our stuff. So what happens if you take everything away and people are just left with who they are and who their relationship is? They’re forced to deal with some stuff.

I wanted to show that in a dramatic, striking, tense and thrilling way. Obviously, much goes on. But the human nature behind that and how we respond is definitely the through-line that fascinates me with this.

Q: Kate Bosworth [Kate] and Emile Hirsch [Michael] worked together on “Force of Nature” [dir. Michael Polish (2020)]. I heard that you didn’t have much rehearsal time. How did you develop the bond between them, and did you allow for any improvisation?

MMD: You really need good actors because if they’re good, they can do their stuff. If you’ve got good actors in good roles, my job as the director is just to provide a safe and nurturing space for them.

Kate and Emile go to some pretty dark places in this movie — it’s intense and vulnerable to expose that kind of performance. I wanted to make sure that I gave them the space and the safe area for them to deliver such incredible performances. Like with Kate, I just [did] two takes; she had to have breaks because it was too intense.

So with good actors in a good part, if you give them the environment with which to really reveal and dig deep, [they will give] great performances.

Q: What was the challenge of shooting in a white room? It can be visually boring, but what you created on that set is mesmerizing.

MMD: I was so happy with how it looked visually. It was beautiful and elegant, but sometimes, it also [got] very dark and heavy. Lighting was a big deal. I had different lighting setups for nighttime. I used dawn setups and midday setups as well. Those different areas really came [across]. We had a lot of room to be otherworldly because you’re in a strange environment.

I had the opportunity to try some interesting things with my DP [that] worked, and we were very happy. We spent most of our money on building that room. It was a big room, a hundred feet by 80 feet or something. We spent most of our time and energy trying to design it so it’s a beautiful piece of architecture. Together with our lights and actors, and solid, beautiful composed frames, you are drawn in by the whole aesthetic of it all.

We spent a lot of time trying to make sure that you were never bored. If you look at it, you don’t actually feel you’re in a white room, visually. You feel like there’s so much happening in there, and it’s so exquisitely framed. We were very, very happy with that. But I think we were conscious right in the beginning of pre-production [to] make this work visually. I knew we had the story, I knew we had the actors, and if we could just make it work visually — it would be a triple threat.

Q: You have had an interesting life. You became a monk, and went to India to meditate. Did you apply any of that experience in this film?

MMD: I did become a monk and moved to India for several years. One of the extraordinary things I saw was what was inside my mind. That’s a fascinating thing to see: how crazy one’s mind can be. And it was a genesis in some ways for this, because we want to see that mind at play. When you take away all the distractions, what’s actually going on inside there?

The other thing that was informed by my time in India was that sometimes you have to go through the fire to come out cleaner, brighter and more mature on the other side. You can’t go around and can’t run away. You can only go through the fire.

In this movie, Emile and Kate go through the ordeal and the fire of that experience. They come out with characters that have grown. As everyone sees, both characters had to undergo a great purging of unhealthy toxic things to get through to the other side where they become lighter, happy people. So yes, in many ways, that did mirror my time of living in ashrams.

Q: What was the decision that you didn’t show the professor Boyan, it seems more intimidating to have an only female voice there — like Hal’s voice in “2011: A Space Odyssey.” What was behind the decision not to show Professor Boyan, the guy who created this setting?

MMD: We definitely wanted the voice in the room to feel as impersonal as possible so that the characters weren’t able to get relief from who they were in any way. That was a very conscious decision. The professor is the intelligence behind all this. For me, this was always a bit like God or the Divine being.

A surgeon will often perform surgery on a cancer patient and that’s painful. In one sense, the surgeon’s got a knife and he’s cutting into someone, but that’s benevolent and kind behavior to help someone by taking out a tumor. This is what’s happening here in the room. This force is benevolent and kind, although it seems like these characters are going through hell. In the end, they come out, in a sense, cured of some toxicity that they had.

Q: Was it a conscious choice not to have the flashback of Kate and her father, as well as flashbacks of Kate and Michael’s past?

MMD: There’s no flashbacks in a sense. What’s happening is the one time there’s a video that gets played live for them in the room that triggers all of this, because it’s live with the father and the sister.

During the trip scene, I took a lot of creative license to show the subconscious and we all took from that license what we could use. Visually, it [offered] some relief from the room as well. I can do something completely grounded in reality, in a sense, because someone’s having a trip. That gives me an opportunity to do something strong visually.

For me, everything has to serve the story. The story is about a strict taskmaster. Am I serving the story here? Am I increasing tension?

Q: When this film opened at the Mammoth Film Festival, the audience talked about what they would do if they were in the same situation, which is different from the reaction of the actors in this film. What was the most fascinating response or conversation that you had with the audience?

MMD: When they were watching it live at some of the festivals, I saw that people really wanted to laugh because they needed some relief. It’s so tense. It’s an engaging movie and you’re drawn in quickly and it’s pretty intense. So when there were these little moments of relief, people really took to them, and I took it as a good sign that people were needing relief because they were so engaged emotionally in it.

Some of the jokes and stuff landed better than you’d think. But I understand now that it was people needing relief from the tension. So that was quite surprising.

Q: What about the choice of music and sound in the background? It’s very minimal.

MMD: Music is this underrated thing. It’s actually worth 50% of the movie, we give it five percent of our energy. I always try and spend more time if I can on the music. My editor, Megan [Brooks] did such a good job offline finding moments musically that really, really helped. Steve London, our composer, took off [in] the direction that she started with.

I thought it really helped, particularly at the end. There were these industrial-type, grinding-gear things which really worked. Music is the unsung hero in this and, I think, with a lot of good movies. Get your music right and you’re getting a lot right.

Q: In that film’s very confined setting, other staff and cast have already bonded when Ashley Greene comes in at the middle of the film. How did you create the circumstances for her to work smoothly with the others?

MMD: Thankfully, her role in the movie is the cat among the pigeons, which is [that] she’s not meant to fit. It’s meant to be very disruptive when she comes. So I didn’t in any way bring her in earlier, and I just had her come on the day and do what she had to do. That was exactly what it was meant to be: a catalyst for chaos. And she did that fantastically.

Q: What do you want the audience to take away from this movie?

MMD: You’ve got to deal with your stuff because it’s not going away. There’s a saying, an unpleasant truth is better than the most beautiful illusion. So it’s better to deal with our reality because it is, after all, reality.

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.