We are all hodophiles, i.e. people who love to travel. But not all of us explore the countries we visit in a responsible way.

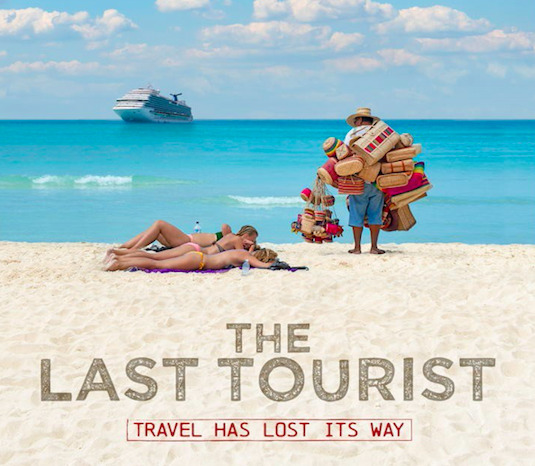

The piercing documentary The Last Tourist, directed by Tyson Sadler — that he co-wrote with editor Jesse Mann — discloses the unsustainable consequences that are caused by mass tourism. Among them is the exploitation of animals for entertainment shows, voluntarism that is increasing the number of children in orphanages and secluded places that are being polluted beyond control. Through it all there is a profound Westernisation of any kind of experience around the world.

On the other hand, there is a silver lining in this mass phenomenon, such as initiatives of women empowerment in developing countries and the chance for certain communities to have a livelihood that would no longer be achievable through agriculture.

The film is a wake-up call to respect locals and landscapes that welcome us in their nations. The documentary features interviews with visionaries such as Dr. Jane Goodall, Lek Chailert, George Stone, Meenu Vadera, Jonathan Tourtellot, Judy Kepher Gona, Gary Knell, Bruce Poon Tip, Costas Christ and Elizabeth Becker. Through their testimonies we witness how “Overtourism has magnified its impact on the environment, wildlife, and vulnerable communities.”

The Last Tourist was presented at the pre-opening event of the 22nd Innsbruck Nature Film Festival, and has been traveling around the festival circuit from Vancouver to Santa Barbara, from Denmark to Germany and will soon be heading to the ECOCUP Green Doc Film Fest in Georgia. In the United States, the film is available on Hulu and is being distributed in Asia, Oceania and Europe.

In the Exclusive Interview, director Tyson Sadler takes us on a journey (pun intended) through the making of this eyeopening documentary:

Q: How do you travel and did that in some way inspire you to make this film?

T.S.: My personal approach to travel is one of immersive exploration, seeking to connect with diverse cultures and environments on a deeper level. This experiential journey inspired the creation of The Last Tourist. Through my travels, I witnessed the profound impact tourism can have, both positively and detrimentally. The desire to share these insights and promote a more responsible approach to travel, one that respects the planet and its inhabitants, became a driving force behind the film.

Q: You co-wrote the script with Jesse Mann, who also edited the film, what was the process as you worked together?

T.S.: Working with Jesse Mann was an incredibly collaborative process. We shared a common vision for the film, and our partnership extended beyond traditional roles. From co-writing the script to the final editing stages, our communication was open and fluid. She demonstrated some visionary thinking in order to weave the stories together. The film would not be what it is without her input. This dynamic allowed us to create a narrative that seamlessly conveyed the urgency and complexity of responsible tourism, ensuring that our original vision remained intact throughout the editing process.

Q: With your crew you filmed in a variety of countries, how long did it take and how much of it was planned as opposed to stories you discovered along the way?

T.S.: The filming process spanned a transformative 2 1/2 years, taking us to 14 countries. We shot over 400 hours of footage — which our editor, Jesse Mann, had to patiently analyse to bring the story to life. While we approached the documentary with a meticulously planned framework, a significant portion of the storytelling unfolded organically. Embracing the unpredictability of each location allowed us to capture authentic and unscripted narratives. The stories we discovered along the way enriched the film, offering a nuanced and comprehensive portrayal of the global impact of tourism. For example, we met a painter in Siem Reap, Cambodia who created oil paintings to sell to tourists in Angkor Wat. He invited us into his life to learn more about how tourism impacted him and his family. It’s a beautiful moment in the film that wasn’t planned prior to filming in Cambodia.

Q: The film starts from the premise that we are born explorers, and we witness how tourists are unconscious consumers, do you think this is because we are also innate colonialists?

T.S.: The Last Tourist invites viewers to consider whether unconscious consumerism in tourism is rooted in innate colonialist tendencies. This exploration serves as a catalyst for introspection, urging audiences to question and reassess their travel behaviours. By acknowledging our instinctual desire for exploration, the film encourages a conscious approach to tourism, fostering responsible global citizenship.

Q: Travelling is often about taking a break from daily obligations. Do you think this is why people tend to be more wasteful on holiday and disconnect with the sustainable issues we hear about in the news every day?

T.S.: The escapism inherent in travel often leads people to disconnect from daily obligations. However, The Last Tourist suggests that this shouldn’t be a justification for wasteful or unsustainable practices. The film advocates for a transformative mindset — one that encourages travellers to be mindful and make informed decisions, even during leisure, fostering a harmonious coexistence between exploration and environmental stewardship.

Q: Amongst the various interviewees, who surprised you the most with their insight?

T.S.: While each interviewee brought a valuable perspective, Lek Chailert left an indelible mark. Her insights challenged preconceptions and injected a distinctive layer into the documentary, offering a fresh and unexpected viewpoint that enriched the overall narrative. Lek Chailert is a renowned conservationist and the founder of the Elephant Nature Park in Thailand. Her approach to tourism is deeply rooted in ethical and responsible practices, particularly concerning the well-being of elephants and the broader ecosystems they inhabit. Lek is a vocal advocate for the rights and humane treatment of elephants, and her efforts have significantly influenced the way tourists interact with these majestic animals.

Q: Do you think social media has had an impact in transforming tourism into a status symbol?

T.S.: Social media undeniably plays a pivotal role in transforming tourism into a status symbol. The constant pressure to share aesthetically pleasing travel experiences online has contributed to the rise of “Instagrammable” destinations. This social validation-driven approach to travel magnifies issues like overtourism, emphasising the need for a more conscientious and thoughtful approach to sharing our journeys.

Q: Soul-washing is something very frequent nowadays, whether it’s greenwashing, pink-washing or rainbow-washing. Do you think voluntarism in travel is connected to this phenomenon?

T.S.: Volun-tourism in travel can, at times, fall prey to soul-washing, where individuals engage in volunteer activities more for personal fulfilment than for making a genuine positive impact. The Last Tourist acknowledges this potential pitfall and encourages viewers to approach voluntarism with authenticity, ensuring that their contributions genuinely benefit the communities they aim to serve.

Q: You finished filming in 2020, when the world went in lockdown and people couldn’t travel. Have you recently heard from some of the people whose livelihoods are based on tourism?

T.S.: Staying connected with the individuals we met during the production of the film has been an interesting process. Their livelihoods depend on tourism and our communication has been both humbling and enlightening. The pandemic’s profound impact on these communities has emphasised the vulnerability of their economic structures, underlining the urgency of addressing and fortifying the tourism industry against such unforeseen challenges. When tourism nearly stopped in Ecuador, one of the film’s main characters who runs a homestay lost nearly all of his income. For many, tourism supports their way of life, their families, and their children’s education. When the world went into lockdown, it was very difficult for many who are reliant on tourism to survive.

Q: Your film has travelled around the festival circuit and has been distributed in several countries. Have you received feedback from spectators who have changed their traveling behaviour after watching it?

T.S.: The response from viewers has been deeply gratifying, with many audience members expressing a tangible shift in their approach to travel after watching the film. It’s encouraging to learn that The Last Tourist has not only heightened awareness but has also motivated viewers to adopt more responsible and sustainable travel practices. The Last Tourist is also being screened in schools and universities. It’s been incredible to see the film take on a new life and to witness the many productive conversations that follow.

Q: The Last Tourist aims to educate the new tourist to make informed decisions when travelling, can you share the initiative that is present on the film’s website that provides online courses on the matter?

T.S.: The online courses are not yet available. They are still in development. Once complete, this series of online courses on responsible tourism will delve into practical insights, real-world examples, and actionable steps, empowering individuals to make informed decisions while traveling. By offering educational resources, we aspire to cultivate a community of conscious travellers committed to positive change.

Q: What do you think is the most urgent issue in rethinking the way we should travel?

T.S.: Undoubtedly, the most urgent issue in rethinking travel is overtourism. Immediate attention and collective efforts are needed to address this challenge. Implementing sustainable solutions, promoting responsible tourism practices, and fostering a global mindset shift are crucial steps toward ensuring that travel becomes a positive force for both the travellers and the destinations they explore. As a global travel community, we need to move towards slow tourism. Slow tourism is important for its commitment to sustainability, cultural preservation, and community support. By encouraging eco-friendly transportation, longer stays, and meaningful interactions with local communities, slow tourism minimises environmental impact and promotes authentic cultural experiences. It contributes directly to local economies, supports small businesses, and fosters a more relaxed and enriching travel experience, contrasting with the fast-paced nature of mass tourism.

It also emphasises responsible travel behaviour, contributing to the long-term preservation of both natural and cultural heritage. Overall, it’s a more mindful and sustainable alternative to traditional tourism practices.