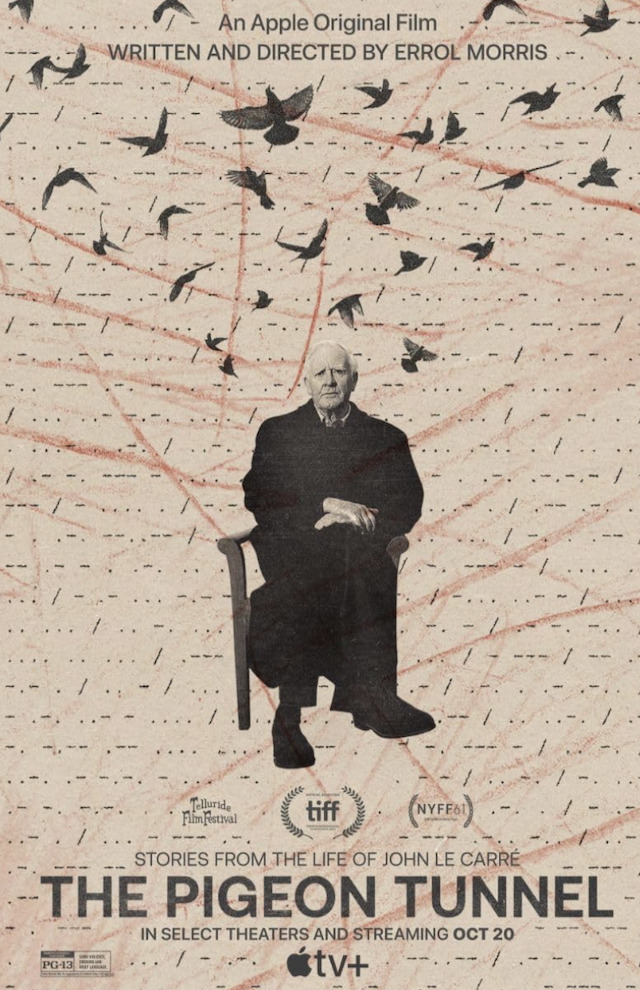

Synopsis : Academy Award-winning documentarian Errol Morris pulls back the curtain on the storied life and career of former British spy David Cornwell — better known as John le Carré, author of such classic espionage novels as The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy and The Constant Gardener. Set against the turbulent backdrop of the Cold War leading into present day, the film spans six decades as le Carré delivers his final and most candid interview, punctuated with rare archival footage and dramatized vignettes. “The Pigeon Tunnel” is a deeply human and engaging exploration of le Carré’s extraordinary journey and the paper-thin membrane between fact and fiction.

Rating: PG-13 (Brief Language|Some Violence|Smoking)

Genre: Documentary

Original Language: English

Director: Errol Morris

Producer: Errol Morris, Steven Hathaway, Stephen Cornwell, Dominic Crossley-Holland, Simon Cornwell

Writer: Errol Morris

Release Date (Theaters): Limited

Release Date (Streaming):

Runtime:

Distributor: Apple Original Films

Production Co: Storyteller Productions, Hero Squared, 127 Wall, Fourth Floor Productions, The Ink Factory, Apple Original Films, Jago Films

Exclusive Interview with Composer Paul Leonard-Morgan

Q: You composed for films like “Limitless” and “Dredd.” You are one of the greatest composers out of the cyberpunk genre. How did this project come to you because working with renowned composer, Philip Glass would be like having the cherry on top.

Paul Leonard-Morgan: I started off at the Conservatoire at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama. I was classically trained. I’ve always worked in the classical world, written my concertos and stuff. I don’t just do film music. But then I started producing bands and doing string arrangements for them. I started working on the electronic side. That’s where my kind of music comes from.

When “Limitless” came along, I had been working with this band No Doubt, I had been doing some drum and synth programming and I had this sound. That was kind of the “Limitless” sound. Everyone was like, “Here’s this electronic dude. He does great electronica.” I did “Dredd” and various other soundtracks based on that. I did video games because they liked “Battlefield: Hardline” and “War Hammer.”

Then I got into cyberpunk — everyone knew my electronica sound. At the same time, I was doing a lot of real orchestral classical work with Errol Morris, the director of “The Pigeon Tunnel.” I’ve done, I think, six films with him now. Philip Glass had done his first three. “The Thin Blue Line” being his most famous with Errol — that had really set the sound for Errol’s films. There’s a lot of momentum, a lot of driving force in the music.

It’s not like typical documentary music which is low in the mix and very sparse. Errol just has music driving and telling the story. I’d worked with Philip. We had a thing called “Tales From The Loop” — an Amazon series. That was my first collaboration with him. It went really well. People seemed to like the music. It was a wonderful experience.

Errol said, “Well, look, I’ve got this film on John Le Carre that I’m doing and would adore it if you would do it. You’ve done all these films for me, Phillip’s done all these films for me. I would love it if we got the band back together and actually did a collaboration with the three of us. Not only do I get to work with the greatest documentary maker alive, but I get to do it with the greatest living composer in Philip as well. Where can it go wrong?

Q: There’s such a vast works of Philip Glass from opera to film soundtracks. You have this unique cinematic style using orchestra-like electronics. How do you manage the collaboration? Where did you start with Philip?

Paul Leonard-Morgan: First of all, as a collaborator — whoever your collaborator is, whether it’s a director, a dancer or a composer — you’ve got to get on their wavelength. You need to know what they’re thinking. You have songwriters for pop songs and they’ve got to get in the room with the artist to know where they’re coming from.

You build up a rapport and most importantly, a trust. You’ve got to get them to trust you. If you’re putting your heart and soul out there, you’ve got to trust that person. I remember the start of “Tales from the Loop.” I met Philip in New York at his house. He was making me a cup of tea and said, “I’ve told the story a few times, but you write the most fantastic melodies.” He was on youtube checking out my music. I was like, “This is Philip Glass!”

I don’t get starstruck because I work with a lot of people but it’s like, “Your melodies are phenomenal, I don’t understand why you do this with your chords.” Suddenly this cup of tea is going cold because he takes me upstairs to his studio to his grand piano and says, “Wll, look, this is your melody” — and he plays my melody on the piano. I was like, yeah, and this was from a completely separate project.

We hadn’t started working together yet. Then he started putting his chords underneath it and I found it fascinating. He said, “Well, I don’t understand why you don’t do this.” He didn’t mean it in a derogatory way. I was like, that’s really interesting. That makes no sense to me whatsoever. It’s absolutely beautiful. But the way that I would do it is like this. It’s really interesting, you start having that conversation and then I would start just taking some of his melodies that he sent over and would put my chords underneath it.

Other times, I would send over my melodies and he would put chords underneath it. That was basically our starting point. You’re just sending stuff back and forth between L.A. and New York and then about two episodes into “Tales from the Loop,” we were just on each other’s wavelength. When this comes along, it makes it a lot easier because by this time you trust each other implicitly, it’s not a case of, “I hope that he doesn’t mind if I muck around with his themes or I hope he doesn’t muck around with mine.”

I muck around with his chords and vice versa. He just does it. There are some people where you worry that you might offend someone but you need to get over that in a collaboration. You just need to go look, “We trust each other. We’re both bloody good. There’s no egos here.” It’s just a case of let’s do it. It was just this wonderful process of sending stuff back and forth and us changing each other’s music until it became one. I’ve got some synthesizers in there but I’ve also got a lot of my orchestral work in there. Philip’s got his piano work and his orchestral work and they’re all gradually merging together until hopefully, it just sounds as one.

Q: How did you and Philip gather the information of what’s on film in order to switch your mindset to his vision?

Paul Leonard-Morgan: I’ve read pretty much every single one of John Le Carre books, [or rather] David Cornwell. Growing up, I was a huge fan. I never actually realized, until the film came out, that a lot of people in the States weren’t necessarily aware of him as a name. When you talk about the books that he wrote that have been turned into films, they’re like, “Oh “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy” and “The Spy That Came in From The Cold.” Oh, yes. I was brought up on them.” I knew it intrinsically.

Philip knew quite a lot of them as well. That’s when we were chatting away about it again and talking to Errol and Stephen, Errol’s editor. It was, “Well, yes, he is a spy novelist.” But if you do a tongue in cheek spy film, it’s going to sound really cheesy. You have some instrumental elements of classic films from the ’60s like John Barry and “The Ipcress Files,” it’s called a cimbalom. This instrument is like the inside of a piano which you play by hitting wires with mallets and that’s got a really cool sound out of the ’60s. We incorporated some of those sounds into our world. It’s definitely not an homage to spy movies as such. It’s more just having a few sounds here and there.

Q: It’s fascinating to compare John Le Carre books with the James Bond films in the ’60s. Talk about the comparison with those spy movies in the ’60s and differences versus novels.

Paul Leonard-Morgan: Le Carre talks about it in the interview with Errol, he says he was pretty pleased that Errol brought up the fact that when his first book came out — which I think he sold, maybe two million or 20 million — but he had sold a lot of those books. This was in those days when it first came out, he said you need to remember that the only spies that people knew about were the Bonds. It was tongue in cheek.

It was the lightness of touch. It was a very cheesy version of Bond which again, was incredibly popular. But his films were all about espionage, spies and Le Carre himself, referencing the fact that, yeah, he did a bit of spy work here and there. People cottoned on to the fact that it was a completely different spy world.

Similarly, with the soundtrack, I guess, it’s like we’re doing hints of a spy soundtrack, but we’re not doing a James Bond film. We’re keeping it very much in our style of music, having different touches to allude to because it’s not a spy film we’re doing. It’s much more about Le Carre telling his story about his father and how his father was a conman and how Le Carre’s life was completely fucked up and changed by who his father was.

Q: The film answers questions about Le Carre’s aspirations and the relationship with his mother as well; she initially disappeared when he was five, and met when he was 21. There’s a moment in the nursing home that addresses what was happening. How did you and Phillip address his mindset? That’s a key element in his life. He doesn’t have a mother or mother figure.

Paul Leonard-Morgan: I took Le Carre to be a wonderful and altogether phenomenal storyteller. But if you look at his life, it’s quite sad to begin with. He said himself, by the end of his life, he’s happy, content with where he was at. But you look at how his life has come about. There’s been a lot of sadness in there to me, yes, his mother figure and the mum walked off because she was sick of his dad’s affairs.

She went off when he was five and left him. We all have our truths, don’t we? One person’s truth is not necessarily the truth. You make up your own stories in your mind about what actually happened. He’s got an image of his mum leaving him at five. But is that actually what happened? I don’t know. For me, the dad, the con man, he can have funny moments. Again, it wasn’t a sad childhood.

He adored his childhood, but it’s these sad moments that changed him as a person. With the dad, he played not exactly the spy part, but the dad was all. He was the con man, a confidence trickster. It’s very easy to go. “Oh, it’s your mum. Let’s have a tender moment and stuff.” there was never that tenderness between them. it was always for us, the wind. We had lots of high wind with reverbs on. It was tinged with sadness. Whenever he thinks back to his mum, it was one of those things that could have been “dot dot dot” when she’s in the nursing home at the end of her life.

It’s not like they loved each other because they didn’t know each other that well. It was much more about, I think the mum believes, I should have had that and I could have had that. She was very glamorous and she liked to be glamorous, picking out clothes from magazines and so on. For me, it was about what’s going on in Le Carre’s head, what is the picture that he’s made of his mum in his head that he likes or makes him happy, right?

Q: Writing is a journey of self discovery. Do you sometimes find in composing your music throughout the film that you find it like a sense of discovery?

Paul Leonard-Morgan: His quote of Graham Greene, who said childhood is the credit balance of a writer, which means that all of those experiences that you have as a child are how you become a writer. you need to write with experiences and it’s the same with music. It’s a case of, “well, you have to start with your experiences somewhere. it’s building up your credit balance, it’s building up your brain. you have more experiences, more exposure to different styles of music or certain musics.

Every job that you do, whether it’s film, dance or whatever they’re all feeding into you. I don’t just write film music. I would go insane just watching a screen every single day. I love the process and love the collaborations in general. I go from a film to working with a band or doing some theater. I love all those different things but each video game and all of those things, you take that experience with you so that we go back to start off in “Limitless” and “Dredd.”

I ended up working on a video game because someone liked the “Dredd” score. I’m working on that, but I’m learning about how to do a video game. I did music for a Disney Ride years ago and it was just when I was doing “Battlefield: Hardline” — of course games are completely different. It’s not just writing a track. You’ve got all these different levels and layers and they have to be loops and so on. It’s a different way of writing. It’s nonlinear, it never starts, it never ends.

You just walk into a scene and write the music as opposed to listening to a track of a soundtrack or CD where you have a beginning, middle and an end. I was working on this Disney ride at the Epcot Center and was like, “This makes sense because you’re standing in one room. Then you’ve got another room over there and another and another. They all want to be playing the same kind of music, the same family.

But if you’re hearing the same piece of music, when you’re lining up for a ride for two hours, it’s really bloody boring, isn’t it? it’s like, “Oh, I’m hearing this piece on loop. What you do is take elements of it — you might have the drum, you might have the full version — in this room. But in that version over there, if it’s also playing the full version, there’s going to be this weird cacophony of sound.

Get rid of the drums and maybe do a melody over there, which is like having a different level on a different layer on a video game and so on. I was like, “This is how you do video games.” All of those jobs you learn something about how to do it, but you also learn about yourself. It’s like, I wonder why I write like that. Do I write a sad theme? Do I write a main theme? Does it make you always question yourself as a composer? What was my life experience that made me do this?”

Q: In this film, Errol Morris and Philip Glass showed what intellectual giants can come up when exchanging ideas. What was an idea of yours that ended up in this film that you were most proud of?

Paul Leonard-Morgan: It’s all very organic. It’s not a case of, it’s all, it’s just a wonderful collaboration. Wonderful. It’s just so funny, isn’t it? You think of him as America’s greatest living composer, but yet he’s just this totally down to earth guy that you just chat away to about them. It’s very hard to explain it if you haven’t met him. It’s not particularly one idea. It was nice when I said we were talking about a particular scene. I was like, “it’s just this bit is too classical. Sometimes you can over-Hollywood a soundtrack, you can make it sound too big.

Obviously, we’ve got a great big orchestra on it and thank you very much at all for and in the factory for supporting us. when I said, “Oh, let’s put in some synths here and there.” It really brought it to life because then it’s a case of it’s not just an orchestral soundtrack. It’s got all these sounds and there’s some crazy modern stuff in there as well. It becomes much more interesting. It’s got more ebbs and flows. That’s why Philip’s music works so well in life because everybody goes and remixes it.

He writes these wonderful themes. He’s got a wonderful sound, but then people will take it [somewhere else]. They’ll do a concerto but then the concerto will have beats on. He writes stuff which is intrinsically able to be married to other sounds. That’s what was cool about this. As I said, it’s not a case of it’s him. It’s me. We just collaborated together on the whole thing and it just became one.

Q: After you finished this film, what tips did you learn from Philip Glass that you might apply in the future?

Paul Leonard-Morgan: To write less. I don’t mean to write less as far as the jobs, I mean to write less as far as I’ve, I have quite dense orchestration in a lot of my music and whether it’s using a lot of strings and then a lot of wind and then a lot of electronica underneath it. What Philip told me was that by stripping it out and just having, sometimes, instead of ba ba, him and his triplets, instead of having all of that, sometimes a little bit of wind on the top, then you have a few bumps underneath it.

It doesn’t have to be as dense. Sometimes it can be just as powerful. It can be just as powerful, if not more powerful by not using as many instruments. because you have more instruments doesn’t make it as powerful. You can get that power from a quartet or you can get that power from a piano or a single wind. It’s just about how you use it rather than relying on the number of instruments.

Q: With Sakamoto’s music when he does the piano, a single note has so much expression.

Paul Leonard-Morgan: Just because it’s one note doesn’t mean that it isn’t being bold, isn’t it? I don’t mean bold as a composer but being bold enough to stand out from the crowd. That one note can be just as important as 60 strings underneath going bum bum bum. Sometimes just that piano goes bum. It’s like,”Wow, where did that come from? Bum bum bum, bum, bum bum bum bum bum.” That is a motif that you’ve got rather than relying on that big glossy sound. It’s much more intimate sometimes and powerful. You have much more of an emotional connection with one person walking into a room. it’s much easier to have a chat one on one with someone rather than one in 60 people. It’s the same when you’re listening to musicians.

Check out more of Nobuhiro’ articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.