Q: This history of Indigenous people spans 250 years. How did the concept for this film come about?

Miki Magasiva: Mario and I were looking for exciting projects to be a part of. At that time, the NZ Film Commission just happened to send out a call on their portal asking for submissions to this initiative called Nga Pouwhenua. We read the brief and were excited,especially since it was a rare opportunity to have a joint venture with our sisters and brothers in Australia. We sent in our scripts and ideas and the rest is history.

Danielle MacLean: We were asked to respond as filmmakers, to the 250th anniversary of Captain Cook’s landing and the British take over of our lands. Each of the teams came up with a response from their own perspective that [addressed] colonization, survival and our resilience in some way. Originally, these eight films were going to be made as stand-alone films and screened together. But as we spent more time together with the other filmmakers, we decided we wanted to be more challenging. We wanted to see if an anthology film could be built from separate writer and directors’ visions and if intercutting these stories could be more impactful than a series of shorts.

Renae Maihi: In our first development gathering, it was clear to me that this film needed to be about endurance and survival. There were numerous stories that floated around. However, in order to achieve the full scope of what my story instincts were telling me, I knew we needed one film set back in time to the early colonization of the Māori. I approached Tim, the writer/director of “Te Puru,” and told him that he should abandon the other idea and pursue “Te Puru” because we needed the expanse of time. He agreed. It was in his heart to tell this story of course, and so, at that stage, the time expanse became possible.

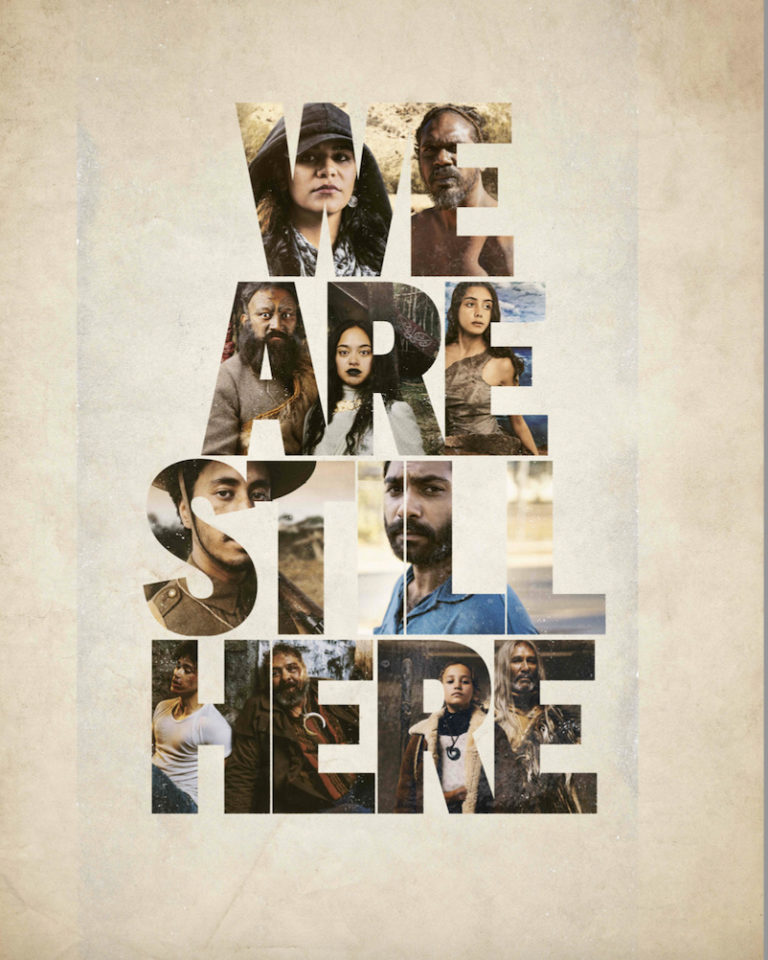

I was living in Toronto at the time with my partner who is a First Nations Canadian. They have a saying up here, “we are still here,” which acknowledges not only their strength but also their endurance. I wrote that down as an offer on the title and it was chosen in the end. While I had no official power in this process, I was always sitting back trying my best to guide the vision that I could clearly see from the beginning and that is, that Indigenous people are resilient, have survived and will continue to survive.

Q: The film opened with “Lured,” written and directed by Danielle MacLean. It depicts a mother and daughter of the Warumumgu [tribe] showing women fishing together in a canoe at sea. It was really engaging and set the film’s tone by exploring the ramifications of the British invasion of the region. The film displays the towering British ship,which came out from the sea, like a ghost vessel. How did you map that out; did you create it from scratch?

Danielle MacLean: “Lured” is set on the East coast of Australia at Kamay (Botany Bay) where Captain James Cook first landed his boat, the HMS Endeavour, on April, 29th, 1770. While my cultural connections are to the Warumungu and Luritja peoples of Central Australia, the imposing symbolism of the Endeavour was utilized to explore the devastating effect colonization had on all the indigenous peoples of Australia, Aotearoa [New Zealand] and the pacific regions beyond.

The traditional fishing line continues to be made today by a select few, as too are the hair-string belts from Central Australia. The string was used as a symbol to talk to the ongoing connection, blood lines, song lines and dreaming tracks that were not erased by colonization. The old people’s presence is still there, even in the busy towns and cityscapes. These remain as places of significance. Our people are drawn back to them and have ongoing obligations to them.

I worked with animator Huni Bolliger and Dan Hartney to create the animated pieces. Shot against green screen, “Lured” was made with a combination of digital rotoscoping and keying. 2D graphics/animation and 3D animation. Digital painting and collage techniques were used to treat the footage and create the environments.

Q: Samoan filmmaker Chantelle Burgoyne’s “In Blankets” is set in 2274. The climate has collapsed and the land’s poisoned. How do you see the future of the current crisis of environmental issues through the eyes of indigenous people?

Chantelle Burgoyne: One of the commonalities that indigenous peoples around the world share is an intrinsic link to the land and natural environment that surrounds us. With that comes an inherent sense of respect and guardianship for it. So much of our language is borne of the land and environment. For example, in Aotearoa, Maori are the tangata whenua, people of the land and Pasifika [Pacific Islanders] are considered tangata o le moana, people of the ocean, as we come from the island nations of the Pacific Ocean or Te Moana nui a Kiva.

Indigenous ways of knowing and caring for our environment have been around for thousands of years but much of that knowledge has either been lost or ignored in the modern era to the detriment of the earth that we live on. I think that returning to being guided by indigenous principles regarding the land and environment may be a key to guiding us through whatever climate catastrophe we are no doubt on a collision course for.

In terms of “Blankets,” through the story that Tiraroa Reweti had written, I saw both a physical and metaphysical manifestation of this as our young protagonist Kōtiro has known nothing but the post-apocalyptic world that she has been raised in. Yet she collects artifacts of the natural world in a pouch that she wears — there was actually a deleted scene at the beginning where she picked up a frozen seed from the ground and put it in her pouch. She has been taught indigenous knowledge and guided by her koro [grandfather]. In many ways, I saw Kōtiro herself as being a seed as she represents the continuance and resilience of her people. No matter what, she will move forward in the world knowing where she came from and who she is. She will survive and preserve [the knowledge] against even the greatest of odds.

Q: Directors Tim Worrall and Richard Curtis’ “Te Puuru” is set on the eve of the fateful Battle of Ōrākau in 1864. Indigenous people debated whether to fight the invading British forces, or stay out of it. Is this an origin story of how the mighty haka war dance started? The performances of Tioreore Ngatai-Melbourne and Te Wakaunua Te Kurapa are incredible — how do you cast them?

Tim Worrall and Richard Curtis: This is the origin story of the Ngai Tūhoe haka Te Pūru [The Bull]. The events depicted in our film are based on the real-world history of the tribe’s entry into the wars of resistance to colonial invasion. The haka was first performed at the actual 1864 gathering depicted in the film where it was used to influence and inspire our tribe to travel to support the Waikato tribal confederation which had been invaded by the British Imperial Army. The haka talks about the British Army and the colonial government as a vast bull advancing, eating everything in its path, leaving only death and destruction in its wake. The haka goes on to implore Tūhoe to strike at the heart of the enemy. It is still performed at our funeral ceremonies and gatherings today and is our equivalent of a national anthem.

The casting of Tioreore and Te Wakaunua was a critical component of the film. It was a non-negotiable for us that all the roles in the film be played by members of our Tūhoe tribe who were also fluent speakers of Māori. Tīoreore is an emerging star in Māori cinema, already racking up a number of strong performances in successful New Zealand films such as “Hunt for the Wilderpeople,” “Cousins,” “Whina” and others. She was always our first pick for the role of Te Mauniko and thankfully she agreed. Te Wakaunua has never acted before but his casting was a direct request from the sub-tribe who descend from the chief Te Whenuanui who is depicted in the film. Te Wakaunua is one of those direct descendants from Te Whenuanui and initially took the role begrudgingly at the behest of his relations. We knew that he had the DNA, the Māori language fluency and the bearing of his ancestor. The beautiful discovery was that he also had the willingness and commitment to be vulnerable as well as emotionally and spiritually available as an actor.

Q: I was really affected by the story of the devastating Gallipoli campaign in “The Uniform.” Directed by the Samoan duo, Miki Magasiva and Mario Gaoa, the film captured charismatic actor Villa Lemanu as a soldier stuck in a trench who strikes up an unlikely friendship with a Turkish opponent. One wonders if we only see who they are just before they try to kill each other. It seems to be a hypothetical notion like John Lennon’s song, “Imagine.” It seems there ‘s a strong will behind it.

Miki Magasiva and Mario Gaoa: That’s an interesting idea to think about. Perhaps for a feature film; if anyone’s looking to invest in that, we’ll be happy to explore it further! No, I think one of the messages in our story is, if we really look at each other, and really see each other, we’re not all that different. If we focused on that more, perhaps there wouldn’t be so much conflict, war or oppression. That’s the thing about filmmakers, we can be the “dreamer”, like John sang about. We hope our films will have a message that starts or continues conversations to a world living more harmoniously.

Q: In director Beck Coles’ brilliant “Grog Shop,” Clarence Ryan plays a painter who flirts with a bottle shop clerk. He is soon interrupted by an aggressive Dan Humphries as a cop. It was fascinating to see them not engaged in conflict, but rather finding a way to laugh it off. Showing this as it evolves, how did this story come about?

Beck Cole: Writer Samuel Paynter and my chapter of We are Still Here always intended to give our audience a laugh and maybe a little heart flutter. The film deals with some hard-hitting topics, colonisation, displacement, racism and more. I wanted to address the issue of alcohol consumption and dependency within my hometown, Alice Springs in Central Australia, in a way that wasn’t too heavy hitting but instead left its audience with a sense of hope.

Q: Director Dena Curtis’ frontier war massacre story, “Woke,” resonated with me about an indigenous man, Kawaregannre, who helps an invader connect with his family. How important was it for you to depict the indigenous people through their caring and kindness?

Dena Curtis: Despite perceptions that indigenous people are quite welcoming and accommodating, it was important to me to portray this in my chapter of the film. But the film itself wasn’t about being accommodating. It was about making the point that Riley needed to go back and take responsibility for his actions, and if Kngwarraye had to be accommodating to achieve this, then he would do what he needed to do to ensure his family got peace.

Q: “Rebel Art,” written and directed by Tracey Rigney, is set during the Invasion Day protests in Naarm [Melbourne]. It follows a homeless young graffiti artist. Stuck in my mind was the phrase, “Decolonize Your Mind.” What does that mean to you?

Tracy Rigney: This can be interpreted in many ways and for me I feel it’s essentially about us taking back our power. It’s about reclaiming what was almost obliterated because of invasion and attempted genocide. It’s about language revival, it’s about land rights, it’s about water rights, it’s about strengthening culture and communities; it’s about healing and it’s about remembering who we truly are and evolving as First Nations people in this contemporary setting to help dream up an inspiring future for generations to come. It’s also about being vocal for the generations who preceded us who had no platform to be vocal. And it’s time for the colonizers to sit and listen to us.

Q: In “The Bull & The Ruru,” directed by Renae Maihi, there is something beautiful to be found in darkness as the young man finds unexpected answers through his encounter with the ‘Ruru.’ While the story is inspired by a past event, it’s relevant to today as police brutality and incidents continue to happen in other countries as well. Were there any current events that you pulled from for the story? Why was it important to tell this story now?

Renae Maihi: My film had a lot of things that were unfortunately cut from it so the themes I intended for it were lost on the cutting room floor. This film is actually about a young man who goes to seek his long-lost father in the last place he heard he was, as part of the resistance in New Zealand. Raised in Australia, his sense of belonging, and his understanding of his cultural identity as a Māori was lost to him when his father, also grappling with PTSD from the war, abandoned him as a child. During Rob’s time of desperate need, when he is contemplating ending his life, he goes in search of his father and instead finds his people and the support he needs. “The Bull and the Ruru” is about cultural alienation, the trauma that intergenerationally affects fathers and sons, and the emotion of anger which is a surface emotion of hurt. Set in the reality of an external struggle for power in a world that seems unjust, the internal story deals with alienation from culture, tribes and family — common experiences for many Indigenous people in colonized countries. “The Ruru” should remind those who feel alone at disparate times in their lives that no matter what, you are not alone and your people are always there with you in spirit. The guardian bird, The Ruru — his ancestors — never left Rob; he only had to turn to see it and believe.

Q: It’s difficult to innovate within the anthology format, partially because of its structural limitations. But there are successful films like “Thirty-Two Short Films About Glenn Gould.” How did you make this one so engaging and exciting? What were the challenges you faced?

Tracey Rigney: We came up with a script that we edited too — but this didn’t translate from page to screen at all, which was challenging. So, we had to start from scratch and felt our way through it with lots of collaboration and feedback. All we knew was that we wanted to weave our films together for the greater good of the whole shape of the film. We had to offer up transitions at the end of scenes and beginning of scenes as a way to help the flow of the film. We also toyed with the idea of having a character breaking the 4th wall which I think worked a treat. In the end, there were motifs like an element we used in each story and I think that this really enhanced the way the anthology film worked.

Danielle MacLean: It’s always difficult to make a film by committee and there came a point where Beck Cole, working alongside editor Rolland Gallois, had to take control of the intercutting of the feature film, rather than everyone just working on their own film.

Chantelle Burgoyne: When we all first came together in Kangaroo Valley in Australia, we decided, as a group, that we wanted to interweave our stories which was definitely easier said than done. A lot of respect must be paid to Beck Cole who ultimately oversaw this in the edit alongside our editor Roland Gallois as it was certainly a mammoth undertaking. But for each of us in our individual chapters — at least speaking for myself — I wanted to bring as much truth and heart to the story that I was telling that I could because I knew that it was an important story. Like all of our stories, that contributed to the larger whole of the entire film. I think when you come from a place of authenticity at the core of a film then hopefully there will be people that find resonance and engage with it.

Renae Maihi: For me as a director, the major challenge was not being able to weave the stories in the edit suite, something that I’m naturally familiar with. I had actually just directed an interwoven play in Toronto so I was really keen to get into it (and I’m an editor too). The challenge was waiting to see what they did with it. The major challenge, and is still to this day, is that I’ve lost a lot of my film in this process. I hope, however, to release it in its entirety in the near future so people can fully understand the depth and breadth of the story I was trying to tell.

Q: What do you want audiences to take away from this film?

Tracey Rigney: I want audiences to absorb and experience each moment of the film from our perspective. I want them to feel and connect on some level and be moved or challenged in some way. That’s all.

Danielle MacLean: I hope that audiences come away from the film with an understanding and appreciation that we, First Nations people, still feel deeply connected to our ancestors and to our country and that colonization didn’t erase that connection.

Chantelle Burgoyne: I want people to be provoked by this film and be left thinking about the perspectives and struggles of indigenous peoples — not just in the past, but also today and continuing into the future. I really do hope that it’s a film which leaves an imprint on audiences.

Renae Maihi: I guess a sense of understanding for why Indigenous people may have trauma and a respect for our endurance and will to survive despite it all.

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.