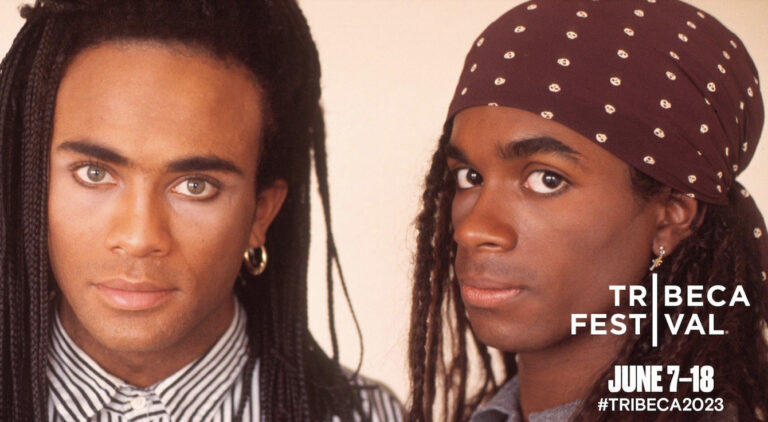

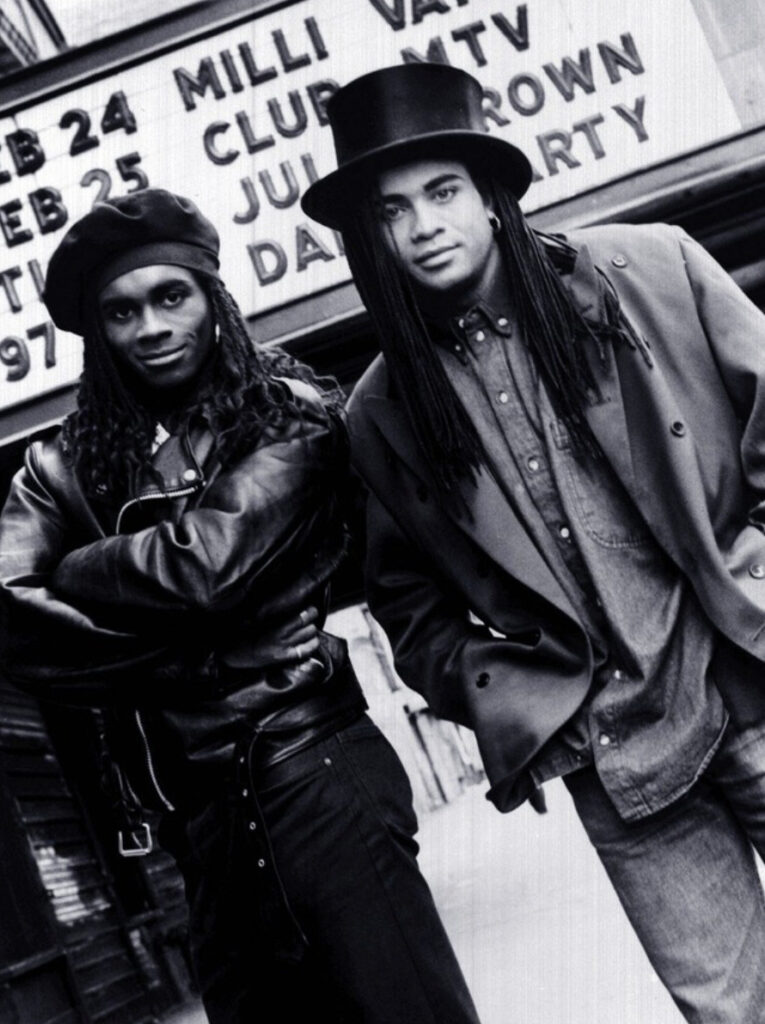

Synopsis : Rob Pilatus and Fabrice Morvan became fast friends during their youth in Germany. With Rob coming from a broken home and Fabrice having left an abusive household, they shared a similar upbringing, as well as a future goal: to become famous superstars. In a few short years, their dreams came true. Their first album went platinum six times in 1989, and their hit “Girl You Know It’s True” sold over 30 million singles worldwide. Rob and Fab, better known as Milli Vanilli, became the most popular pop duo in the late 1980s. However, their ascension to success came with a devastating price that ultimately brought their undoing.

Luke Korem’s Milli Vanilli dissects the duo’s trajectory from their humble origins through their collaboration with legendary music producer Frank Farian — a toxic partnership that cemented the band’s fate and concealed a shocking secret about their music and craft. With access into the inner circle of those involved in the controversy, including Fabrice himself and Farian’s assistant Ingrid Segieth, Korem’s illuminating documentary pulls back the curtain on the story that we thought we knew, but didn’t, and delivers a compelling look at the price of fame and the opportunistic commodification of artists.

Genre: Documentary, Biography, Music

Original Language: English

Director: Luke Korem

Producer: Luke Korem, Bradley Jackson

Runtime:

Production Co: MRC, Keep On Running Pictures, MTV Networks, Fulwell 73

Q&A with Director Luke Korem, Producer Bradley Jackson and Editor Patrick Berry

Q: Luke, what inspired you to start this project?

L.K: Bradley and I were brainstorming ideas for our next project. We have worked together for 12 years now. We thought about Milli Vanilli. We were both like seven, eight years old when the whole thing went down. We always remember the VH1 episode, [VH”1’s Behind the Music”]. It’s just so ingrained in your head. I remember watching this video on YouTube of Fabrice [Morvan] in New York City at the Moth telling his story. At the end he sang, and he had this great voice.

I thought, “Wait a minute… I thought the story was that these guys can’t sing.” That led us down a rabbit hole, and there’s something about Fab — his persona, his presence, he’s so calm, and you can tell he’s dealt with it and moved forward in his life. Then we thought about Frank [Farian, creator/producer of Milli Vanilli], and that Frank had done this before with Boney M. We were like, “Uh oh.” Then we tracked down the real singers, and everybody down [the line] Credit to Fab — he’s had a lot of filmmakers over the years approach him.

He was here last night [at Tribeca], he sent his regards. But I will say, when he watched it — he hadn’t watched the film until two weeks ago — he gave us complete control which I think was important. But when he watched it [here] with the audience, it was very, very emotional for him. Especially when he could hear them laughing. He’s wrestling with it all. But in the end, he was so overwhelmed with joy.

He’s like, “I just felt so great that people hear the real story.” And that was why he decided to do it with us, because he was like, “I can just tell that you want the full story.” I also wanted to put a camera in front of everybody and let them see. Because it’s 30 years ago, and the way people remember things, who’s to say exactly [what is] the truth of certain things? The only way to do that is let everyone speak and the audience decide. That’s the summary of that.

Q: Patrick and Bradley, what made you sign on?

B.J: Luke nailed it. I’ll just say we have a couple of people who worked on the film as well, in the audience. We’ve got our composer and writer of the original music. [Applause.] There are just so many great artists that worked on this film. I just wanted to give a shout out to everybody who worked on the film.

Q: Pat, why did you decide to work on this, other than you love and adore us — and we paid you money?

P.B: That sums it up [laughs]. But I would say yes to any project that these guys brought me. We worked on it before, and they had this idea and I was an immediate yes. Beyond that, the story has so many layers, obviously, and aside from the fact that it’s something that maybe you thought you knew — or maybe you didn’t — it has such a great human component to it.

One thing I think I love most about it is that it has a positiveness to it, and with so many stories today that have a lot of darkness — and this story has a lot of darkness — but something that I really like and that Fab brought to life so well, is he’s able to have that positive message. I think the film captures that, and really says that even in the darkest times, even in the toughest situations, humans can persevere through. I found that immediately something that I could relate to and love that part of the story.

Q: How did you work at the process to arrange it all together?

L. K: A lot of people worked on this film. Hanif Willis-Abdurraqib is one of our executive producers. I was like, “You’re so good, you’ve got to get a cameraman.” He was fantastic. We had archive producers. Bradley and I did a whole deep-dive, like a lot, a lot. I think we knew that this film deals with a lot of different things. It deals with grace, with the machine of pop music, with exploitation, perseverance, lies, and deceit. We needed a collective, and sought out people.

We did a lot of test screenings, and asked, “What do you think about this element of the film? How can we improve it?” We really worked hard on that to make sure that we were hitting all the notes. Also, in a documentary, you let the people talk. Charles [Shaw, one of the actual singers from the original session] just tells you straight up what happened, and I think the best way is just to let people tell you what happened and then respect it.

Q: The real cautionary tale is that most of the record business is fake. Producers produce the records, songwriters write the songs, and sometimes the singer actually has more to do with it than be on the stage. You made that point but if you hadn’t had Fabrice — being the way he is — would you have had a movie? He was was so fantastic. You lucked out. You guys did a great job with him.

L.K: If he were here, like last night, he can say it better than we can. He has this indomitable spirit about him. I mean, he forgives Frank Farian. He looks good, because he knows this thing will eat you alive. I just — I get emotional. I have so much respect for the guy. And his family, for opening the doors, and being like, “we’ll just open up.” So yeah, without Fab, obviously we don’t have a film. One other thing: it’s really important that we have Rob’s [Pilatus] voice. This is equally about Rob. He’s not here today, and we were thankful to get some audio.

B.J: We were very lucky that that audio came our way, and just because I feel like Milli Vanilli is two people, oftentimes people would go, “Well, who’s Milli and who’s Vanilli?” and I would laugh. But deep down, I would go, “No, these are two real people who live real lives and had a real tragedy and heartbreak, and there’s two sides of the coin.” There’s Rob, and then, there’s Rob battling addiction. Fab spoke to so beautifully last night, that he sees Rob as two people — the person who he was before addiction, and the person he was while he was addicted. And that audio [you hear of Rob talking], that was [recorded] 45 days before he passed. That’s why he speaks so [candidly]…

L.K: Fab also made a good point, that he hopes that young artists watch this film. And I like to joke that this is a hundred-minute advertisement for why to get a good entertainment lawyer.

Q: How did you navigate all of the red tape around the record industry? You got some heavy hitters to speak, how did you do that?

B.J: Oh yeah, a lot of red tape. I’ll let Luke handle that because Luke has a velvet glove, a velvet hand, when he does this stuff. And then there’d be the occasional chainsaw. Call him the velvet chainsaw.

L.K: We’re not doing something sensational. We’re not doing “gotcha” journalism. We’re going to ask you questions, you give us your truth. That’s it. That’s all we did. I think people respect that, even Ingrid [Segieth]. She was there last night — and guess what, she likes it. She’s like, “That’s me.” [We got] the Arista executives — I don’t know if they’ve seen it.

I have a lot of respect for Ken [the one really candid record exec]; the guy is like “The Sopranos.” He just tells it like it is. I love his interview so much. But otherwise, it was just a lot of [nos] — we went up to Clive [Davis] through great channels. Of course, he was not responsive, but we had the archive of him straight up saying what happened years ago.

Q: You did a great job at using all the archival material.

L.K: I was saying this movie is so dependent on great archival footage. Pat was also a big person, this guy, and Lauren [Ospala, archival producer], just incredible amount of rich detail. There’s so much stuff that we didn’t include, we could have made a three-hour movie. There’s an entire back-story about the song “Girl You Know It’s True” — how Frank stole that from a Baltimore hip-hop crew and they didn’t even know anything about it. We wanted to include it, it was this wild left turn — we had the movie and the scene is amazing. Pat did such a good job cutting it.

B.J: Maybe our distributor will let us release that.

Q: The three of you deserve to be commended for centering on race the way you did it. You showed how a lot of the reaction had an underlying racist element to what had happened.

L.K: One of the things we had to remove from the film was a backstory of Frank. The fascinating thing is that he was a German Schlager (pop music) singer, a solo artist, and had a semi-successful career. But he liked Black music. And they said, “Well, you’re a white “Schlager” singer and that’s [not going to] work.” So he thought, “I’m going to be a Wizard of Oz” [the man behind the scenes controlling it all].

He even told people, “I’m Black inside.” So the race part was something, and that’s why we had people consulting with us and making sure we were getting it right, doing screenings and testing, and letting people like Hanif — it was a predominately white audience and these guys are black, and that’s part of what they faced because of that. I really appreciate you saying that, because that was something that we worked really, really hard on.