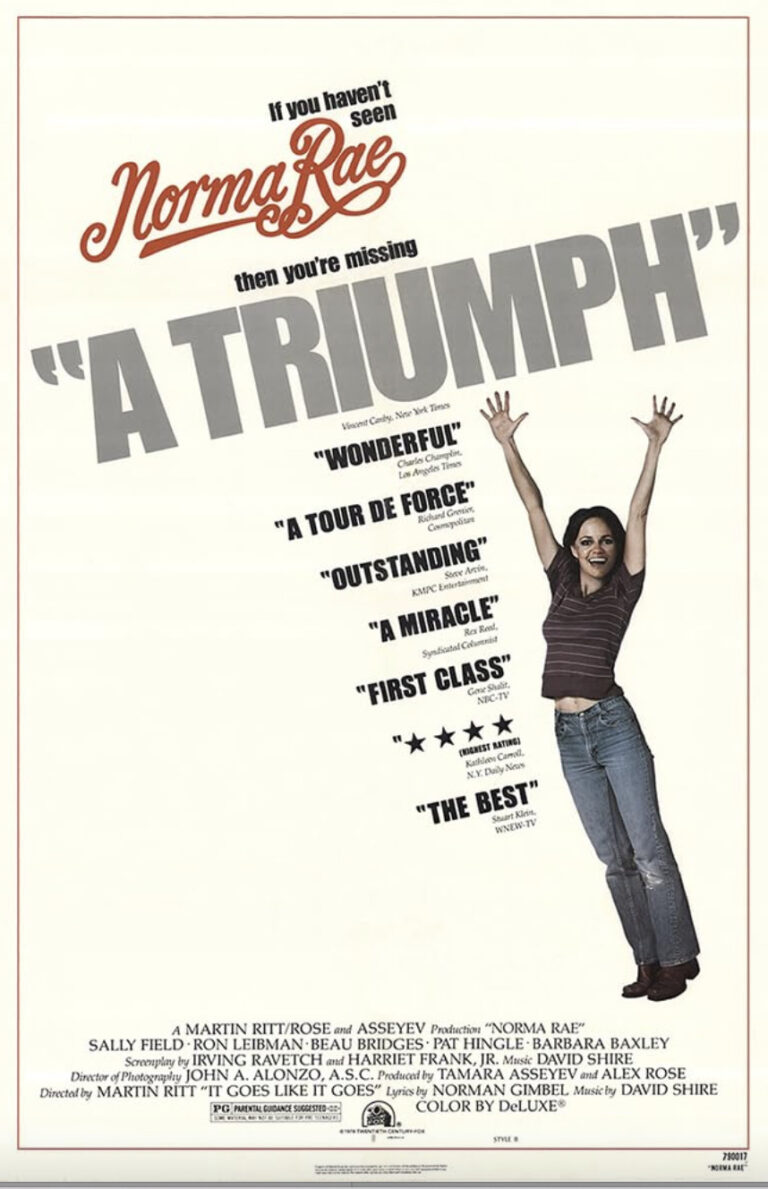

WIF (Women in Film) hosted a screening of Norma Rae (1979) at Vidiots in Los Angeles. The screening served as the kickoff to WIF’s Screening Series celebrating iconic films by the decade made by women and people of underrepresented genders in honor of the organization’s 50th anniversary.

Lake Bell moderated a panel discussion with the film’s star Oscar-winning actress Sally Field and Oscar-nominated producers Tamara Asseyev and Alexandra Rose. The event took place prior to when the SAG-AFTRA strike began.

Q&A with Actress Sally field, Producers Tamara Asseyev and Alexandra Rose

Q: The first question is for the producers Tamara Asseyev and Alexandra Rose. First of all, you are two very strong female producers. Can you speak to this current climate? Looking back to what it was like then at the time this was made, to take a controversial subject in particular, this book that you optioned, can you speak to the process and how that came about?

Tamara Asseyev: Everything we tried to do was difficult. Two young women in a male dominated industry was very difficult, but a political story was almost impossible.

Alexandra Rose: I had been in film distribution. I met Tamara who was a budding producer — the first producer in Hollywood to make movies on her credit cards. Roger Corman, for whom I worked, was a wonderful supporter of women. Yes, all the women were in the office — so we got together and decided to go into business together. I found this article in the New York Times three years before, but I knew it couldn’t be sold. Then “Rocky” came out of nowhere, right? Starring nobody and it was a gigantic hit. Suddenly I said, “We have the female version of “Rocky”. Yes. That triggered the cash register in a few people — in Martin Ritt and Alan Junior’s mind. So Guy McElwaine, the agent who put it all together and of course, Martin who was right on it.

Tamara Asseyev: Guy, who unfortunately passed away, was our agent. We had dinner one night and I said, “Alex and I looked at ‘Hud’ and [thought that] Marty Ritt would be the perfect director for this film. And he said, “It’s very funny. I’m going to have dinner with him tomorrow night. Get me a synopsis of the story.” So he had dinner with Marty and his wife, and called me the next morning. He said we were at Warner Brothers or no? We were, yeah, Warner Brothers and Marty was at Columbia, but it was all one lot. And he said, Marty would like to talk to you girls. Can you go over and meet him? So we went over and met him and he said, “Well, it’s an interesting story. If you get a writer that I like, I’ll read the script.”

Alexandra Rose: I think he even said if you get Irving Ravetch to do this, I’ll consider it.

Tamara Asseyev: Anyhow, it was tough. By the time we got back to our office, Guy called it and said, “Marty, those two pretty actresses have a good idea.”

Alexandra Rose: By the way, we were known in Hollywood as “The Girls.” All the business affairs people knew us as the girls. We were always called the girls. Everyone knew who the girls were because we were the first female producing team in the history of Hollywood. You’re in the right room for that.

Q: Once you had this incredible entity, you started to package this really special story and film. How did Sally Field come into your orbit?

Tamara Asseyev: It was so difficult for a long time. First thing, how did we get the film financed to begin with and get it written? Guy McElwaine’s best friend was Alan Ladd Jr. and he was head of production at 20th century Fox. That year Fox had made “Star Wars” and made a lot of money and Alan Ladd decided he’d take a flyer on some difficult films if we cut our salaries in half.

Alexandra Rose: That’s right. And we had to. It was very good in a sense because we had a gross position to make up the salary. But we had to show that as filmmakers. Marty Ritt also had to cut salaries in half.

Tamara Asseyev: So we all did because we all felt very strongly about the film and, and we’ve never seen a penny of our profit. By the way, we did, finally, sue.

Alexandra Rose: A little teeny bit, but the film was so successful and Sally won best actress at Cannes. And that was the most tearful, exciting moment. Laddie was even crying. We all started crying, we were sobbing.

Q: It was so amazing. Sally, can you get involved in this conversation? How did this script come to you?

Sally Field: I had already been an entity because I started in television in 1964. This movie was made in 1979 and I was in situation comedy television in the ’60s and you don’t get out of that. Not if you’re a woman, you don’t get out. If you were a man and you were doing Maverick or were Steve McQueen and he came out of television, but as a woman in situation comedy television, you died there. But I just would not let that go. I wanted to be an actor. That’s what I had come out of high school and junior high school. It was my voice with myself.

I then worked with Lee Strasberg and blah blah, blah. I did all of this and was inching my way through, slicing my wrists and saying to myself, ”If I wasn’t where I wanted to be, it wasn’t because of the big them who wouldn’t let me in the room — which they wouldn’t — but I wasn’t allowed to come in the room and audition for anything or even be on the list. It was because I wasn’t good enough. If I could keep my own power and it rested in me and incrementally, I made my way to something.

My first audition was for a little tiny film that Bob Rafelson did called “Stay Hungry.” Then, a wonderful casting woman named Diane Crittenton, recognized something [in me.] Also I had been at the Actor’s Studio long enough to create some sort of underground reputation in those days when you could do that. She then brought me in for another audition where no one in the room wanted me there. You could hear them. I’d be waiting to go in and I’d hear people there saying, “What the hell are you wasting your time for?” I knew then how to use that anger that I felt. I knew how to use it as fuel and not let it just make me unravel.

I came in for my second audition that Diane Crittenton invited me to, which was for something called “Sybil” and no one wanted me there. No one in the room wanted me, but it had to be that good. I had to be, I had to come in as “Sybil” and not think in my head I would ever get out. There was a time when I didn’t think I would get out of Sybil. They saw me, and had mentioned it to Marty, but Marty was an Actor’s Studio baby. He came from that world. He began with Lee in the group theater and he knew this world. He too saw “Sybil;” I was still fighting for a spot. Give me a spot. Let me audition for something where I can do what I now know how to do.

This was the first thing that came to me. It came to me when I was in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, doing a girl role because I had two kids. I had to survive. It was a screenplay from Marty Ritt who was known as a real actress’s director. I read the script on the plane on my way to L A to meet with Marty. No, I didn’t. That’s not true. They weren’t able to get it to me. I had to read the script. So I got off the plane. My mother had read it. She was taking care of my two kids and I said, “What is it about?

What is it? I don’t know. I have to get ready.” And she’s like saying, “Well, it’s like this really downtrodden thing. It’s kind of depressing.” I went into the meeting with Marty dressed in beige because, I didn’t know why, I had no character to come in as, and Marty said to me — and I will never forget this… He didn’t say all those things like, you know, “Blah, blah, blah, what do you think at all?” He said, “Are you serious about your work?”

I said yes. He said this has been altered for three or four other women, and by then, seven other women. I was hoping it was only three or four but ok, seven — every one they could think of that had ever been in a movie before, or started in a movie before. But they had all turned it down. And Marty said to me, he believes that things happened as they were supposed to happen, that no one in the studio wanted me, that he wanted me. If I read the script and wanted to do it, he’d fight for me and win. He did and I was there.

Tamara Asseyev: I want to say one thing about Marty Ritt. He was a blacklisted director and actor so he knew how to fight. Right. Yes.

Alexandra Rose: He had made his living becoming one of America’s top racehorse handicapper because that’s all he could do. And he fed his family handicapping racehorses.

Q: This is already a wild story, but once you read it — your mom read it first — and she approved even though she thought it was downbeat as it were. Anyway, so you in the process, right? Of all of you as filmmakers making this piece, what sort of research and brunt work of getting into the headspace of telling a story with this kind of accuracy.

Tamara Asseyev: It was a true story to begin with. The guy who wrote the New York Times magazine [article] wrote the book and we auctioned the book and it came with the real person, Crystal Lee Jordan —she became Crystal Sutton [with her second marriage]. We had shown “Sybil” to Alan Ladd Jr. and his team and they said fine. We were ready to go and the Ravetchs [Irving and his wife Harriet Frank Jr.] had written this wonderful script. They were a husband and wife team and you can see both of their abilities in this film.

Suddenly we found out that the girl, Crystal Lee, thinks that we’re all too Hollywood and she doesn’t want it made. Barbara Kopple, a brilliant documentary filmmaker, wanted to do a documentary about her and hired lawyers. They were going to break the contract. Ok. So Marty and I flew to North Carolina. All I remember is an all-night flight. We had to spend the night and [see] our attorney. Anyhow we were to meet her and show her who we were and how earnest we were. We weren’t Hollywood, right. But we never got to meet her, just her lawyers who said, “We’re going to sue you.”

Alexandra Rose: Fortunately what had happened was, she had had a very early contract with Warren Liefermann, the person who wrote the book and Fox was so strong. Laddie said, “We’ll pay what you want. And he made the salary for the book, the option was very high. And then they said, “Ok, got it.”

Q: Let’s speak of the financials for a second. In the notes, it was initially slated to be [shot in] 40 or 54 days, but then ended up being shorter because of the way it was shot, which was by Martin Ritt and it went well.

Sally Field: That was Martin Ritt and [director of photography] John Alonzo. And it was me.

Q: Can you speak to that — that’s really interesting.

Sally Field: First of all, it was unusual because it’s something we don’t do today. Unfortunately, we had two weeks of rehearsal, which was invaluable and you don’t do that today. Rarely do you have like 24 hours of rehearsal on even the biggest of films. In those days we were there in Opelika [Alabama] and were living in it. I was working in the mill, meeting everybody. I could hear the language and we had two weeks of rehearsal.

So we were really ready to go. The fact that the brilliant cinematographer John Alonzo was shooting it all handheld, and very, very few were shot with dollies or any of that. It was mostly Alonzo holding the camera on his back and or was his operator John Toll, who is a brilliant cinematographer today. We were shooting so fast. Marty knew exactly what he wanted.

There wasn’t any fluff. He didn’t like doing things just in case he needed it. We were there and sometimes, in the day, we would have to slow down. He would say, “You know, we were finished at noon and he’s like, “This isn’t good. The studio is going to think we’re just phoning something in, let’s just slow down.” So, we ended up with way less days than we were scheduled to shoot because we were so fast.

Tamara Asseyev: And half a million dollars less.

Alexandra Rose: Yeah, which is huge. In those days [that was] what? We were $6 million. That was a big film. That was a good sign. So to knock off half a million, that budget was fantastic. And it was Sally and Marty. That was with two weeks of rehearsal on location that we had there.

Q: I just want to clarify, you were able to work?

Sally Field: I was working, I got to work in the mill. I wasn’t very good at it, I must say. But yikes, that wasn’t easy. We were there with the weaving machines. I was able to understand what was actually done, how the throttles worked and all that. I was awful. God forbid anybody should use that fabric for anything that I made was full of holes and it was awful.

Q: It feels improvisational at times even though I’m seeing they’re shooting this in one shot. It feels like it either could be extremely well rehearsed and scripted or a little off book. Can you speak to that?

Sally Field: I work very improvisationally, but I knew that and had such great regard for the Ravetchs and this magnificent script that had been handed to me. So I would work alone at home and knew things I wanted to do and pretend it just came out of my mouth. I wormed my way in without making a big deal out of it and saying, “I think I want to do this” and have them go, “No, I think not.”

I wasn’t going to give them the chance to say that I was just going to, oops, that just came out. I needed to find Norma’s humor. Humor makes you care about somebody more because it means they’re not taking themselves too seriously. You had to see Norma’s humor and I had to find my way into that. It wasn’t always on the page so I would noodle my way into it.

Q: When you said the rehearsals were for you, were they with the entire extended cast or just the core players?

Sally Field: Beau was a little late because he was doing another film. but Ron and I were there. And the others, Pat Hingle, brilliant Pat Hingle was there. The other thing about this film, and you guys can say this, it was so important to me. So many of those players are the real deal and a lot of them are real locals, they never acted before.

A lot of them were local actors that came from community theater and they came from, and you feel that I felt that working with [them]. We were improvisational when we had meetings, sitting around the living room. I remember one time we had that scene where we’re sitting around the living room talking about our grievances. There was a young black man there who just began to speak and he wasn’t supposed to speak.

But he spoke because it was what was going on with him and it killed me. It was so real and exactly what his life was like. It was what he was feeling and he was just caught up and we were talking about this — what was really happening. A lot of that is going on in the film, with the locals be they white or black, be they male or female.

Tamara Asseyev: Since it was a true story, it was a JP Stevens story. The mills wouldn’t rent us a mill. I went to New York. I met the head of the union and with help, and finally he said, “There’s this one mill owned by a family in Chicago and they’re going bankrupt.”

Q: They were selling the place anyway.

Tamara Asseyev: He said, “Try him.” So he tried them. We got that mill. That’s where we shot. Also, we hired every worker in the mill, like Alabama.

Alexandra Rose: So they even said no. But Fox knew they were going bankrupt and offered them a huge amount of money and suddenly it all changed. The politics in the South in those days were lamentable. And what’s interesting is how much is still going on today — that was exactly going on then.

Tamara Asseyev: We went to look at locations.

Alexandra Rose: I thought the Civil War had ended. I’d never been to the South and I was shocked.

Tamara Asseyev: Yeah. There’s so much in this film, culturally and socially — and obviously in the climate that we [are] in now, with the strikes in our industry.

Alexandra Rose: When we were shooting, Ron [Liebman’s] speech [he was playing Reuben Warshowsky] was really important. That was a big deal. And we shot that because John Alonzo had not wanted to bring a generator. We’d hook up to electrical [outlets] wherever we went. In that old church, the electrical was faulty, but no one could see that until the film was sent to the lab in Los Angeles. It had a flicker like a globe to go on and off through his whole speech.

So we had to, at that point, beef up the electrical in that church and Ron had to do the whole thing over again. When we were working in the church, these two lovely blue haired ladies came up and said, “What do you all want to do with this ugly little black church? We got a nice white church around the corner. You should be shooting there.” I mean, that kind of thing was just a common parlance. It was just like that. I too hadn’t been to the South and it was really surprising to us. Right.

Tamara Asseyev: But I have to say one thing. When we saw the first first tapes, you know, you send them to the lab and come back and look at them. The first day was the scene with Sally saying, “What is it?” That first day in the middle and we knew that Sally — it’s right from the daily — we knew she was a star.

Q: Looking back on it, this is an iconic movie and it resonates so much right now.[Sally], your performance is so powerful. Audiences are screaming and clapping for you in that moment when you hold that sign. It’s iconic and you perform that as such a young woman. It’s really important. All of you, you’re tremendous filmmakers.

Sally Field: Women In Film is important. Collective bargaining is important. Yes, it’s what democracy is. Our democracy is being challenged in a big way, but our unions are doing what they do, negotiating and scrambling and they/we will find our way out of this. The writers will. We don’t know if the actors are going to go out even though they’ve been given authority to do that. The directors have settled and our industry will continue to thrive. And the unions are incredibly important in that.

I know as an actor who started in 1964, the changes that have happened from my union fighting to make some changes from when I started in 1964. So it’s incredibly important. They’re important all over this country, and, whoever they are, it’s important to have collective bargaining. You can be wrong as a union. You have union leaders that should be shoved out. Lord knows, you can have bad leadership but you need collective bargaining for the workforce.

That’s the importance of us. That’s what a democracy is. So I’m glad to be here for Women In Film. I’m very proud that “Norma Rae” continues to be what it is, or was. It boggles my mind but it’s “Norma” and not me. When I’ve been asked earlier to do screenings for the Writers Guild, I worried and, Lord knows, I’d be nowhere without the writers but I feel very protective of “Norma” and of this character.

I know she represents someone who stood on a table with a union sign over her head, but that’s Norma, not me. I hope that I would have the guts to do that, but I haven’t as of yet. I may someday, but not if all of us stand together. Then I won’t need to be a Norma. Norma will be Norma. But thank you to everyone for coming to watch this film. It was incredibly important in my life and all of our lives. So thank you.