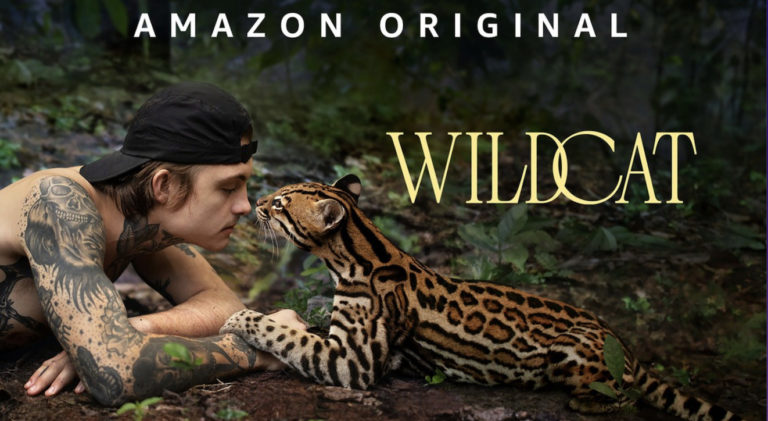

Synopsis : Wildcat follows the emotional and inspiring story of a young veteran (Harry Turner) on his journey into the Amazon. Once there, he meets a young woman (Samantha Zwicker) running a wildlife rescue and rehabilitation center, and his life finds new meaning as he is entrusted with the life of an orphaned baby ocelot. What was meant to be an attempt to escape from life turns out to be an unexpected journey of love, discovery, and healing.

Q: Explain what the re-wilding project is? What kind of research did you do for that program?

HT: When doing a project like the reintroduction and re-wilding of animals, it’s very important, obviously, to not just put the animal back in place where it belongs, but to also document and see the important things that a majority of people wouldn’t have actually gotten when they’re researching an animal. In reintroducing these ocelots, it gave us an opportunity to be so close to an animal and see what type of things it eats.

You can’t necessarily see that with your eyes from a distance. A lot of the stuff that we had already done was working with camera trapping [a camera armed with infrared sensors is placed in the field to remotely capture time-lapsed images and video whenever these devices sense motion], and we camera-trapped a lot of the areas anyway. But a lot of the things I was focusing on was their diet and interaction.

It’s very interesting when you would walk during the day, a lot of the monkeys, when they see a human, make one call. When they saw an ocelot, or a different animal, they would make another call. So when they saw me and the ocelot together, they would be very confused, and would come down the tree — honestly, sometimes I’ll be face to face with the monkey, because they would be trying to figure out why this ocelot was so close [with me].

Not only that, but we’ve found a lot of core relationships and symbiotic relationships between other animals. For example, the giant armadillos and the seven- and nine-banded armadillos in the Amazon rain forest make these huge and incredible tunnel-like systems for their houses. But what happens is, if they don’t look after them every single day, then rodents, other animals and insects come into the holes and make them their own.

What the relationship between the armadillo and the ocelot was, is that they would have this like, friendship, where they wouldn’t hurt each other, but would be very inquisitive of each other. They would give the ocelot shelter by making these holes, and the ocelots, in turn, would eat the rodents that were calling the holes home. They would basically clean out the holes, which were their sanctuaries, forming an armadillo-ocelot kind of duo.

A lot of other things with diet, was looking at what kind of diets they were actually eating. While shooting, we were doing other scat analyses. When an animal eats another animal, DNA obviously goes through its digestive system and then comes out as scat. I was seeing first-hand this ocelot eat lizards, insects, snakes, rodents, birds and the list goes on.

We saw the amount of things that this one animal could eat. At the same time, he was also deterred because of my presence. To do scat analysis on other ocelots was really interesting to see the difference in diet between an animal that was working with a human and a truly wild animal. A lot of these scientific observations have been really interesting. I’ve spoken to a lot of other people about them, and it definitely was a very unique case to be this close to a wildcat.

Q: After you fought in Afghanistan, you had some difficulty over the years. How did you make the transition to going into wildlife and seeing such a different life?

HT: After leaving Afghanistan, I was still based in the UK, in the military, and was not happy. I was struggling with depression and PTSD, and needed to escape. I have found that natural places have always been a very good healer for me personally, and I know that this is the case [for] many other people as well. But I honestly went to the jungle to kill myself. I didn’t want to live anymore, I was extremely down and depressed.

But when I was there, it took me about 14 days to realize like, “You shouldn’t feel this way.” I believe that because I was in this most beautiful and powerful place that I was kind of enlightened, or had an epiphany. I sat on the front of the boat, after a long day adventuring — the sun was going down — and the bats and birds were changing. I had this idea like, “Why do you want to kill yourself?”

From there on, I spent another two weeks in the jungle, and those weeks were the most incredible two weeks — going from very, very depressed to very, very happy was a crazy concept in my head, especially from struggling a lot. The reason I went to the Amazon was because I honestly didn’t know what to do. I didn’t know where to go or how to figure out anything. So I just googled volunteer work in the Amazon and a place came up. When I finished my military time and had gone from this crazy time, I booked a ticket and went to the jungle.

Q: There’s so much danger in dealing with wildlife — hunters, mining, logging, and wildlife trafficking.

What is your strategy to protect the animals and execute the re-wilding plan?

HT: It’s very complex. As someone from England and Sam [Samantha Zwicker] being someone from the U.S., you can’t just go in to try and do these things. It’s very much a “white savior” look on life. You need to have friendships with community members, and need to get their trust. You do that when you’ve spent a lot of time there — we weren’t just there for a few weeks; we were there for many, many years. Sam is actually still down in Peru at [this] minute.

You need to have these relationships and friendships so that you can move. Currently, I work in Ecuador and am making the same friendships and relationships with the Ecuadorian communities. It’s one of these things [where] it’s not a quick process. It’s a slow process, it takes a lot of time. With that, you just have to trust that what you’re doing is going to be beneficial 1) for your projects, 2) for the wild and the environment, and 3) for the other projects that are going to come after that.

Q: Samantha Zwicker, who studied Wolfology in college, established the organization Hoja Nueva. Talk about your first meeting her?

HT: I went to the jungle not knowing anyone. I actually, honestly didn’t even know what language they spoke when I went to Peru. I was in such a dark, depressed state that I just needed to escape.

When I was there I made a lot of connections, and many were conservationists and ecologists. I continued to make friends along the way, one of them being Sam.

She was actually working a camera trap project that she asked me to help with. That’s how we met, just being in the rainforest at the same time and working on projects together.

Q: Your team initially shot a lot of the footage by yourself before the filmmakers became involved. How did you shoot your footage, and at what point did the filmmakers get involved?

HT: The footage of Khan, the first ocelot, is all by ourselves. I spent a lot of my time alone in the jungle filming and filming. That’s all I did. When I wasn’t filming, I was hunting so that I was able to feed this ocelot that needed my help. Every single bit of footage before the second ocelot, Keanu, was shot by myself. Now the filmmakers came on because they had heard — actually Trevor [Frost, co-director] had come to the rainforest to do work with anacondas.

Then from there, he hadn’t actually managed to find many anacondas. It was one of those things where it didn’t work out. When you’re working in natural places, sometimes it just doesn’t. When he was there, our mutual friend was like, “By the way, you won’t believe this guy’s story.” From there on, I showed him some footage on the hard drive, and we talked about making a small documentary. Then about a month after that, when the second ocelot came, we brought down all of the cameras, all of the audio, and I stayed in the jungle for an extra year and a half.

Q: In the film, it’s said that “the jungle here changes people.” How has your perspective of your life changed after living in the jungle for so many years?

HT: I was young, like 18, when I went to Afghanistan. A lot of the times, especially in the UK when you’re 18 years old, you’re able to drink, go out and club, vote — you’re able to do everything, so you’re technically like a man. I was so naive at that point that when I went to war, I thought I was a man. I was so young and childish. A lot of my life has just been about learning from mistakes, and growing with different things, feelings and emotions. I put myself in some very hard situations in my life.

I’ve made that leap of faith and done everything that I felt was right. The thing that I would tell people, when they were like, “I want to do what you do” or “I want to do what you’ve done,” is to follow your heart. If you have a fire inside you, a burning desire to go to the rain forest and do conservation, or be the president of the United States — or wherever you want to — if you have that drive, that push, love and passion, you should do everything that you can to make sure that that’s completed in your mind.

Q: What do you want audiences to take away from this film?

HT: The film is very complicated. A lot of people come to it and think that they’re going to one film, but then come out believing and thinking of it in a completely different way. The unique thing about it is that a lot of people are going to take away different things from this film that have actually happened in their life — whether it be going to war, being in the military, having a family or a younger brother that’s distant, or mental health issues, or just loving wildlife.

People are going to walk away from this film with a kind of connection. I guess the main thing that I want people to walk away from this film believing and thinking is that, if you are depressed, you are not alone, you have the support that you need even if you don’t think it’s so. As dark as some times might be, there’s light at the end of the tunnel. There are places that you can go to make yourself better if you really, really want to.

That’s why I’ve set up a nonprofit called Emerald Arch, and via Emerald Arch, it’s a place where we will be doing fund-raising to buy land in Ecuador. With that land, we’re going to do scientific research on wildlife, to be camera-trapping, and protecting as much land as possible. But also, to make a safe space so that anyone who is struggling with depression, can come to the jungle as a retreat. They can walk the same path that I walked. In being lost and depressed, they can go to a beautiful place and have the time to just re-set. You don’t have your phone, your computer and you don’t have work. It’s just the time when you can re-set. There are always options. I want people to walk away thinking, “It’s not the end of the world. I’m not alone.”

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.