The winning film of the Cinema & Arts Award at the 81st Venice Film Festival arrives in the star-spangled nation. Through this documentary, filmmaker Andres Veiel makes a compelling portrait of one of the most controversial women of the 20th century, a filmmaker entangled with the Nazi party: Leni Rifenstahl.

Riefenstahl uses a variety of material to reconstruct the ambiguous figure of a woman who claimed she was clueless about the horrors enacted by Hitler’s regime. Contemporary filmmakers such as Jodie Foster and Quentin Tarantino have praised her artistry, but only Andres Veiel embarked upon the gargantuan project to dwell upon her political and historical involvement. He did so without being judgmental, but rather by plunging himself in the never-before-seen documents from her estate. Thus, the documentary is the outcome of a thorough analysis of 700 boxes containing private films, photos, recordings and letters that Rifenstahl bequeathed to the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation in Berlin.

Andres Veiel’s Riefenstahl is entrancing as faint images overlap with sepia photos, and crossfade with old black and white footage from World War II. There are also snippets of talk shows from the Seventies and Eighties, such as 60 Minutes on CBS, Lebensläufe on SWR, Tonight on BBC and CBC’s Other Voices. Toby Cornish’s cinematography provides an otherworldly and uncanny atmosphere, whilst the eerie music by Freya Arde instills a sense of wistfulness that gently accompanies the socio-historical chronicle.

Riefenstahl first broke into the German film industry as an actress. One of her early works for the screen is the 1926 motion picture The Holy Mountain by Arnold Fanck, the director of mountain films. This is the cinematic genre Leni Riefenstahl proudly wanted to be identified with. In fact, Fanck directed her also in The White Hell of Pitz Palu and Storm Over Mont Blanc. For the latter Rifenstahl was tethered to a rope and plunged 15 metres in a crevice, risking frost-bite at -20C°. She was the only woman on set. This experience very much epitomised her strength of character and determination in breaking through.

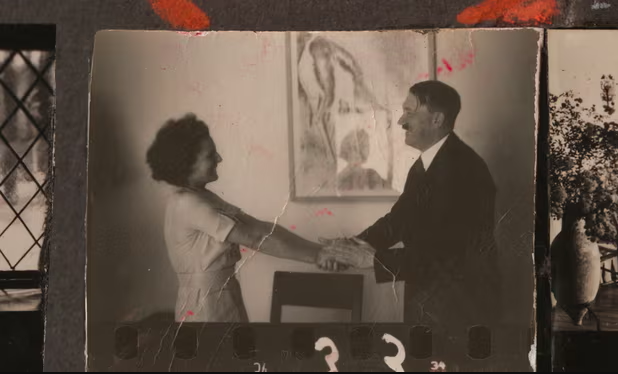

But above all, history remembers Leni Riefenstahl as the Reich’s preeminent filmmaker. She spent decades after the war denying her association with Nazi ideology, and claiming ignorance of the Holocaust. Yet, some of the original footage shown in Riefenstahl seems to testify the opposite. We see a young Leni smiling and holding hands with Hitler, and in their correspondence one of the letters she wrote to him reads: “You know how to bring joy to others better than anyone else.”

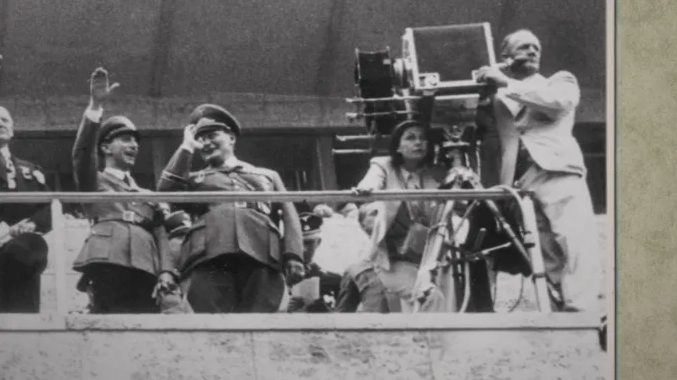

Throughout the post-war period — when questioned during several interviews about her affiliation with the Nazi party — Rifenstahl would always play naïve. She claimed to be politically inexperienced and yet she was the one who was appointed to visually represent the credo of the Nazi aesthetics, by capturing on film the German Olympics in 1936. Her film Olympia, at the time, was the most costly documentary project in the history of cinema, as she coordinated a crew of 30 cameramen.

For the prologue she decided to film the sea at the Curonian Spit, with cinematographer Willy Otto Zielke, portraying Myron’s discus thrower like a statute coming to life. Zielke worked so hard that he suffered a breakdown that committed him to an institution for alleged psychosis. In 1936 he was forcefully sterilised, in accordance with the law of prevention of hereditary diseased offspring. Leni Riefenstahl was informed of this, but did not intervene.

Riefenstahl continued to work as the Reich’s filmmaker and posterity would acknowledge her mastery of montage. The perfectly-staged body worship portrayed in Olympia was also evident in her Triumph of the Will. These motion pictures, were considered by Holocaust survivors, such as Elfriede Kretschmer, as “Pied Piper Films.” They celebrated all that was heroic and victorious, projecting contempt for the imperfect and weak.

In 1940 Riefenstahl shot her last project for the regime, Lowlands, which was based on Hitler’s favourite opera. She wrote the screenplay, directed it and played the leading role, and this film would mark the litmus test of her contradictory nature. She used over 50 Roma extras, many were children. She claimed she had met all the extras once the war was over, when in truth none of them survived.

Andres Veiel’s film is very well calibered in pursing an understanding of the figure of Riefenstahl, without exculpating her in the process. What emerges is the history of family violence that shaped her. Her domineering father would hit her, whilst her stage mother would push her at all costs to stardom. As she grew older, Minister Goebbels was so obsessed by her that, according to her story, he took her by force. Rifenstahl describes this as one of several assaults she had to go through. She accuses also tennis player Otto Froitzheim of rape. However, having been a victim of violence did not stir in her the rejection towards the brutal Nazi Weltanschauung, since she ended up marrying Albert Speer. He was nicknamed “the devil’s architect”, since he had been appointed by Hitler to construct the concentration camps and establish the working conditions of those imprisoned in them. During the Nuremberg Trials he was sentenced to 20 years, which he spent writing his memoirs that, once released, became a global editorial success. Riefenstehal, way after the marriage with him was over, still reached out to him, asking for advice for her own memoirs.

Andres Veiel is brilliant in maintaining the ambiguity of Rifenstahl’s positions throughout the chronicle of her life story. This narrative device evokes the same approach used by Jonathan Glazer in The Zone of Interest, where Nazi supporters would go about their days without questioning the horrors that were being enacted.

Riefenstahl retraces the filmmaker’s entire life, from her youth to her older age, when her plight to defend her sullied reputation was supported by Horst Kettner, her partner in life and work, who was 40 years younger than her. She dedicated over 10 years to collect her memoirs and carried out over 50 law suits for what she considered a slandering of her persona. The justice system seemed to be on her side: in 1949 she was acquitted for the accusations concerning her behaviour during the Nazi era.

The third act of her life was characterised by grappling the task of how she would be remembered by posterity, which lead her to a new cinematic project in Africa. In the Sixties, Riefenstahl took off to Sudan to film the Nuba people. Apparently they took a liking for her and named a mountain after her, Monte Leni. However, some footage shows her bossing around the subjects of her documentary shootings.

Throughout the documentary her high and mighty attitude seems to be the hallmark of her creed, in all the stages of her life. Her old school friends, Alice and Hertha, remembered her as ambitious, at times capricious, and most often a femme fatale. Leni Riefenstahl always staged herself as a star. Even during her final days, in some television interviews she would check how the light would fall on her face.

She lived until 101. She emphasised that she would have liked to be remembered for her film The Blue Light — where she directed herself in the role of a sympathetic witch. Looking back, she claimed it would have been better if her life had ended when she was at the peak of her career, that is in 1939 with the outbreak of the war. In hindsight she never apologised for the artistic contribution she gave to the Nazi regime.

To witness this obdurate demeanour echoes the conduct of leaders of the present time. Hence, Andres Veiel’s Riefenstahl is exceptionally timely, as current affairs expose how totalitarian power can trigger an effect of reverential attraction and fandom. It provides a fully fleshed out example of Hannah Arendt’s Banality of Evil, proving how the figure of Leni Riefenstahl is more relevant than ever.

Final Grade: A