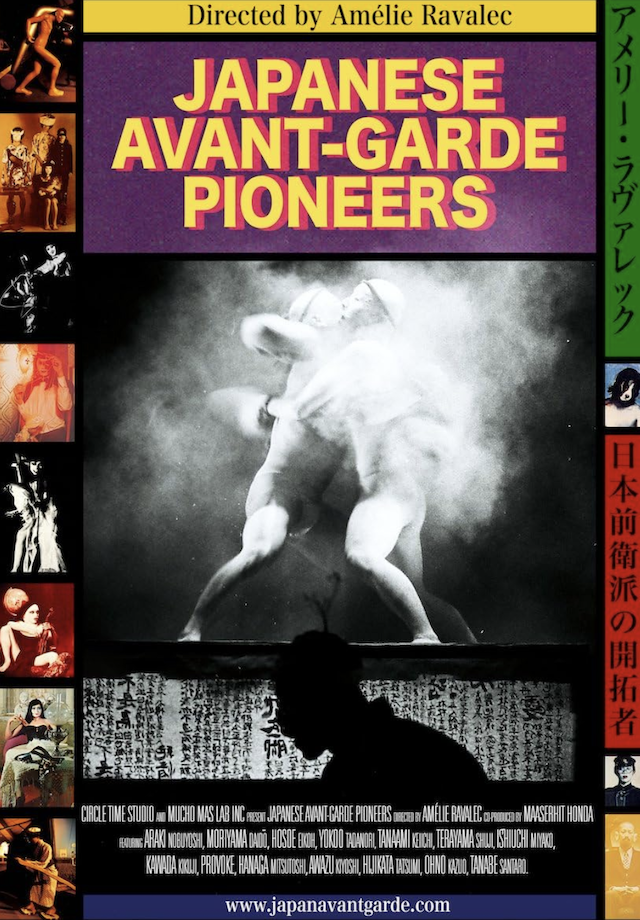

The prodigious documentary directed by Amélie Ravalec focuses on a time of profound social change in the Land of the Rising Sun: the Sixties. Japanese Avant-Garde Pioneers portrays how the turbulent times of the postwar era inspired an artistic explosion across the Nipponic nation, with the emergence of a revolutionary scene of avant-garde artists who spearheaded many disciplines.

The motion picture is all-encompassing, giving space to the various artistic mediums that broke conventions at the time, through the craft of photographers, dancers, performers, graphic designers, and filmmakers. Ravalec has pieced these segments together in a manner that randomly moves from one subject to the next, occasionally with some digressions that may seem irrelevant at first, but turn out to make perfect sense later on.

These snapshots of everyday scenes gave new significance, as artists would try to grasp the “noise” of existence through their lenses. Therefore, photography became a reflection of truth, because “a picture is not just a product of the physical movement, it’s a psychological work, since the cameras are operated by a human being.”

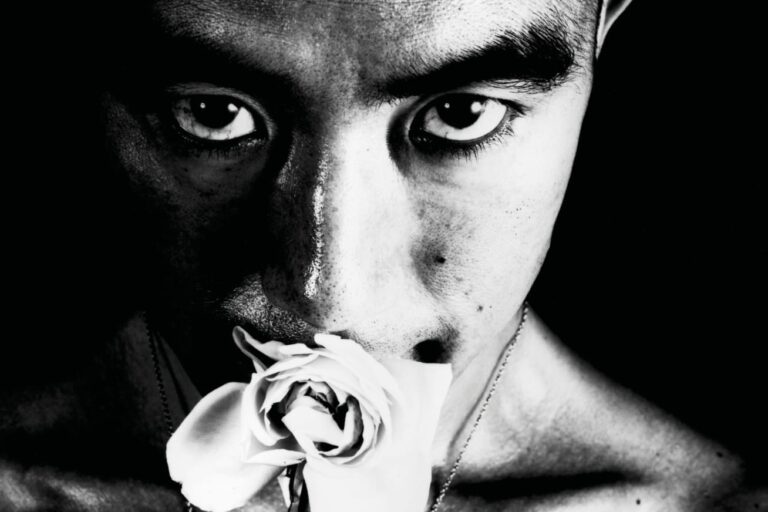

Thus, we get acquainted with the craft of Araki Nobuyoshi, the photographer and contemporary artist known for blending eroticism and bondage in a fine art context. His Sentimental Journey “1972–1992” was a visual diary, chronicling his life with his wife Yōko, who died of ovarian cancer in 1990. Another master of photography featured in the film is Moriyama Daido, best known for his black and white street photography and association with the avant-garde magazine Provoke. He was influenced by the likes of Seiryū Inoue, Eikoh Hosoe, Shōmei Tōmatsu, Andy Warhol, Shūji Terayama (whose oneiric style was compared to that of Federico Fellini and was a disciple of Arak), and Yukio Mishima (the ultra-nationalist author who committed suicide with seppuku).

Another Japanese photographer featured in Japanese Avant-Garde Pioneers is Hosoe Eikoh, whose images are often psychologically charged, exploring subjects such as death, erotic obsession, and irrationality. He was professionally affiliated with experimental artists such as Tatsumi Hijikata, founder of a genre of dance performance art called Butoh, along with dancer Kazuo Ohno. This controlled movement — born under the influence of Western thinkers like Jean Genet, Georges Bataille, Marquis de Sade — was the Japanese take on Surrealism and Dadaism, based on the idea to “resist fixity.” This free-spiritedness found its ultimate representation in a fictional animal called Kamaitachi, a weasel-like demon that haunted local rice fields and slashed wanderers.

Other photographers that shaped the cultural phenomenon of the time include Kawada Kikuji (who co-founded the Vivo photographic collective in 1959 and published the famous book The Map); Hanaga Mitsutoshi (who experimented with photograms and decalcomania, before transitioning to photojournalism and documentary photography); and Nakahira Takuma (who played a central role in developing the theorisation of landscape discourse known as fūkei-ron).

Within an array of male photographers, Amélie Ravalec includes also female photographer Ishiuchi Miyako, who began her career shooting familiar streets and buildings in her hometown Yokosuka, which was transformed during the post-war period into one of the largest American naval bases in the Pacific. Another woman photographer who captured the political scenario of those years was Watanabe Hitomi. Hence, photography fuelled the desire to document different degrees of maturity.

Spectators assimilate how all the different artistic disciplines feed into each other and overlap quite beautifully. For instance, the theatrical art is shown through the work of Terayama Shūji, the Japanese avant-garde poet, artist, dramatist, writer, film director, whose works range from radio drama to experimental television, and especially the underground theatre known as Angura. His “Little Theater” (shōgekijō) reacted against the Brechtian modernism and formalist realism of postwar Shingeki theater in Japan, staging anarchic underground productions in tents and street corners, to explore themes of primitivism, sexuality, and embodied physicality. Also the co-founder of theatre group Sajiki, was an important contributor to stage performance during the 1960s.

Pop art is celebrated in Japanese Avant-Garde Pioneers, with Tanaami Keiichi who was active as multi-genre artist ranging from graphic design, to illustration, from video art to fine art. Also Yokoo Tadanori, has been influential in the pioneering movement, with his signature style of psychedelia and pastiche; the same impact applies to the poster and architecture design by Awazu Kiyoshi.

Tanabe Santaro, would have found fertile ground during our 21st century, since in the 1960s he started a primordial version of upcycling, by following in the footsteps of Western Dada artists. He took discarded materials from junkyards to make his artistic creations, but since there was no way to keep the artwork it was eventually discarded, making his craft very ephemeral.

Amongst individual creative voices, the pioneers also worked in artistic collectives, like the Neo-Dada Organizers (composed of a small group of young, up-and-coming artists who met periodically at Yoshimura’s “White House” atelier in Shinjuku) and Hi-Red Center (that organised and performed anti-establishment happenings).

The magnetic visual journey, through the artistic expression of all the pioneers of the Sixties, is alternated with a few talking heads. The interviewees are primarily modern experts, who provide a sense of context concerning how each of the artists were mirroring the society around them. These include: historian Kaneko Ryūichi, art director Enomoto Ryoichi, author Mizohata Toshio, curator at the Ashmolean Museum Oxford Lena Fritsch, curator at the Guggenheim Museum Alexandra Munroe, Daiwa Scholar Lucy Fleming-Brown, author Peter Tasker and the rope master known as Master K.

The latter makes a studiously engaging excursus on the tradition of Kinbaku, i.e. the use of rope and knots in religion, martial arts, and erotic bondage. This practice testifies how how Japan never demonised sexuality, unlike Judeo-Christian cultures. As long as the Wa — that is the calm of society — was not compromised, people would be free to express themselves as they pleased. What mattered was not to create embarrassment for the collective, and eroticism was not considered to cause disgrace.

The pioneers, each with their medium, possessed the punk ethic, before it came around. Reality was transformed into a giant illusion. Subcultures were seen as more authentic and therefore deserving to be given attention. People who were generally rejected by society were given a spotlight. Disabled people were placed on stage. Women were captured on camera having orgies, in the domineering role, they were finally in control during the era of the body.

Japanese Avant-Garde Pioneers, in the line-up of the 2025 Japan Cuts edition, transforms the political unrest, caused by the aftermath of a horrific chapter in history, into a mesmerising anthology of moving pictures.

The world was warped, that is why artists would embrace styles celebrating the grotesque, the savage, the promiscuous. The film comes across almost as an homage to the chaos of the movement. It shows how the purpose of art was reshaping itself, dealing with the unfathomable. What emerged was a new language, in line with a new thought, that went beyond the nation’s borders: the Japanese Avant-Garde Pioneers impacted the world internationally.

The revolution caused to rethink institutions and question the status quo, creating a new worldview. Artists were seeking new freedom from tradition. The language became more expressive, more experimental, more subjective: pioneers were breaking conventions. It was a time that celebrated mavericks and eccentrics, who were trying to reach psychic truth, through a large dose of fearlessness aiming for spiritual transcendence.

Throughout the documentary Ravalec allows the art to do the talking. This kaleidoscopic cinematic journey bestows a bountiful amount of knowledge. It is remarkable the way she assembled the works of these artists, that usually could only be found in rare Japanese volumes or select museums and are not accessible to all. Japanese Avant-Garde Pioneers has given visibility to a multitude of rebellious artistic genres emerging from a period of turbulence.

Final Grade: A

Check out more of Chiara’s articles.

Photo Credits: IMDb