The 2024 Japan Cuts line-up features an impressive documentary on the past, present and future of sexually explicit art prints known as shunga. Director Junko Hirata has been exceptionally meticulous in bringing together the human stories that mark this Nipponic art form, along with a chronicle of the preservation of these works and public display in prestigious venues such as The British Museum in London.

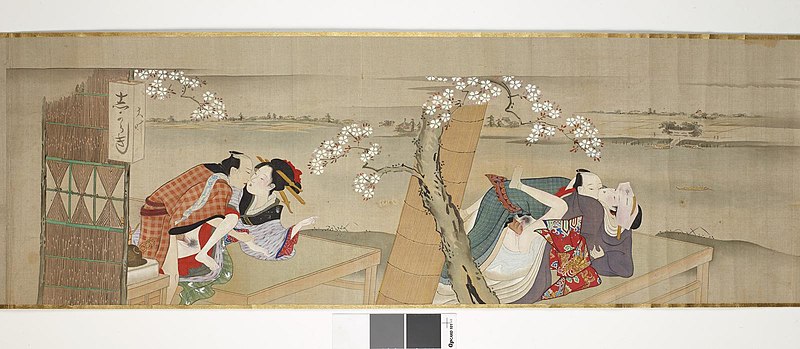

Shunga: The Lost Japanese Erotica begins with the examination of Handscroll for the Sleeve made in 1785, which is a set of 12 prints made by Torii Kiyonaga. This is part of a shunga reprinting project organised by the Tokyo Traditional Wood Printing Crafts Cooperative, in collaboration with the International Research Center for Japanese Studies. From here, the film exposes what might have been perceived as a subject of taboo and presents a tradition spanning centuries.

Shunga: The Lost Japanese Erotica introduces audiences to this creative form through insightful interviews with enthusiasts, collectors, curators, and scholars, including Andrew Gerstle who inspired The British Museum’s historical shunga exhibition in 2013 and Michael Fornitz who owns an auction house in Denmark. The film is very methodical and uses animation and narration (by Moriyama Mirai and Yoshida Yō), to bring the artworks to life, thus creating a sense of realism.

The first images of the movie are of the tip of a chisel, cutting through a block of wood. It soon becomes clear what is being carved. Ke-wari is the technique of carving the fine lines of hair, naturally this includes pubic hair. The craftsman describe the difficulties of shaping its curliness. If some say that ‘God is in the details,’ a comment made in the documentary cheekily claims that “The gods reside in pubic hair.” Lines have to flow with ease and that’s the challenge. Moreover, the way Shunga artists recreated genitalia was indicative of the age of the people depicted, which elected them to an artistic version of medical scientists. Shunga would also portray semen, squirting, homosexual intercourse and oral sex. For the latter, there’s also an outlandish portrayal of a woman being pleasured by an octopus, called Tako to ama that translates roughly to Diver Girl and Octopus.

Junko Hirata digs deep into her cinematic investigation through history, art and sociology. If in Western contemporary society Eastern pop-culture has permeated through Manga and Anime, the origins of it all can be found in the erotic humour of shunga. What gives the illustrations the ironic punch is the grotesqueness of the enormous genitals, whilst embracing a more penetrating (pun intended!) form of storytelling. Shunga had a humanistic approach in describing sexual intercourse as one of the many aspects of life. This is clear in Tsukioka Settei’s Four Seasons, that demonstrates how physical intimacy is an expression that traverses the various phases of existence.

Shunga finds its origins in the works of ukiyo-e artists of the Edo Period, such as Utamaro, Hokusai, and Kiyonaga. That era — that spans from 1603 to 1868 — was more progressive in confronting sexuality. Shunga prints were part of bridal trousseaus: they provided instructions to the young woman on what she was expected to do with her husband, to continue the family line. Also men would be equipped with these drawings. Warriors of the Edo era would keep shunga depictions under their armour as protective amulets, since sex meant expanding the family and hence returning home after the war to do so.

However, even during the permissive Edo period, shunga did confront some oppositions from those who considered this art form obscene. These included the governmental attempts issued by the Tokugawa shogunate in 1661 banning, among other things, erotic books known as kōshokubon (lewd books) and the Kyōhō Reforms, of 1722 that banned the production of all new books unless the city commissioner gave permission. Nevertheless this was nothing compared to the retaliatory Western perception. In Yokohama in 1859, an American traveller described shunga as “vile pictures executed in the best style Japanese art” and by the time we reach the 20th century Shunga was not welcomed in Western museums. This kind of censorship tells a lot about society’s anxieties, that lead to the suppression of free sexual consciousness. Hence, shunga’s development was thwarted by the shift in societal norms. The contamination of Western culture and technologies at the beginning of the Meiji era (1868–1912) — particularly the importation of photo-reproduction techniques also for nude figures — determined the end of the shunga practice.

Something that needs to be stressed is the difference between Japanese shunga and erotic art in the rest of the world. Shunga is first-class art, to the point that its artists have become worldwide acclaimed also depicting other subjects, the most famous of all being Hokusai that everyone identifies with The Great Wave off Kanagawa.

The fascinating trait about shunga is that it was meant for all social classes. While watching Shunga: The Lost Japanese Erotica it’s riveting to discover how the further back in time we go, the less fuss was made upon the depiction of titillating images. In fact, the Japanese influences of shunga date back to the Heian period (794 to 1185). An example can be found with the Tale of the Brushwood Fence illustrations by Jisekian Shujin, that were commissioned by Emperor Go-Shirakawa. Perhaps, as one of the interviewees jokingly expressed, “pornography was a higher level back then.”

If we think about Freud’s psychology, or even the way children have no restrictions in exploring their bodily pleasures, it makes perfect sense that shunga’s eroticism was confronted like a fairytale. This is evident in the fable-album of the Fashionable Amorous Adventures of Mane’emon. These collection of drawings follow the epic journeys of Mane’emon, who after drinking a potion shrunk in size completely. This new state allowed him to travel across the country, and peak into the lives of all sorts of people engaged in sex. Looking at this Shunga piece transforms us into peeping-toms, as much as the tiny Mane’emon, but in a playful manner.

Shunga artists often used pseudonyms, not because of the lascivious nature of their artwork, but because of the precious materials used like silver and gold leaf. It was boorish to flaunt them. Nowadays, the shunga techniques remain unvaried, but the craftsmen aren’t as highly-trained as the ones of past centuries, nor is there the same use of raw materials. For instance, today’s wood is softer and the use of pigments is less refined.

What seems like a long forgotten art form has a very strong presence in our present. Shunga: The Lost Japanese Erotica gathers the testimony of various contemporary artists who have been influenced by shunga. One of them is Tadanori Yokoo, who not only was inspired by this art form, but discovered his 74 year old mother in possession of a shunga piece. He is the one to express how painting can be as visceral as sex, as it flows spontaneously from our bodies through passion and sensory involvement.

Today shunga handscrolls can be found while wandering around Japanese flea markets. Shunga illustrations truly withhold the power of unveiling not a simple depiction of sex, but the historical society of when the art piece was made. The beauty of this artistic form is that it’s never perverse, albeit there have been some darker representation of intercourse, such as humans copulating with animals or the erotic ghost paintings with an elderly woman on top of a man. In history of art and literature lust and sex have often been intertwined, but shunga has ultimately always been about the joy of living. If one thinks about, whether or not people want to be prudish about sex, it’s the reason why we’re still around.

Final Grade: A

Cover photo kindly provided by Japan Cuts.