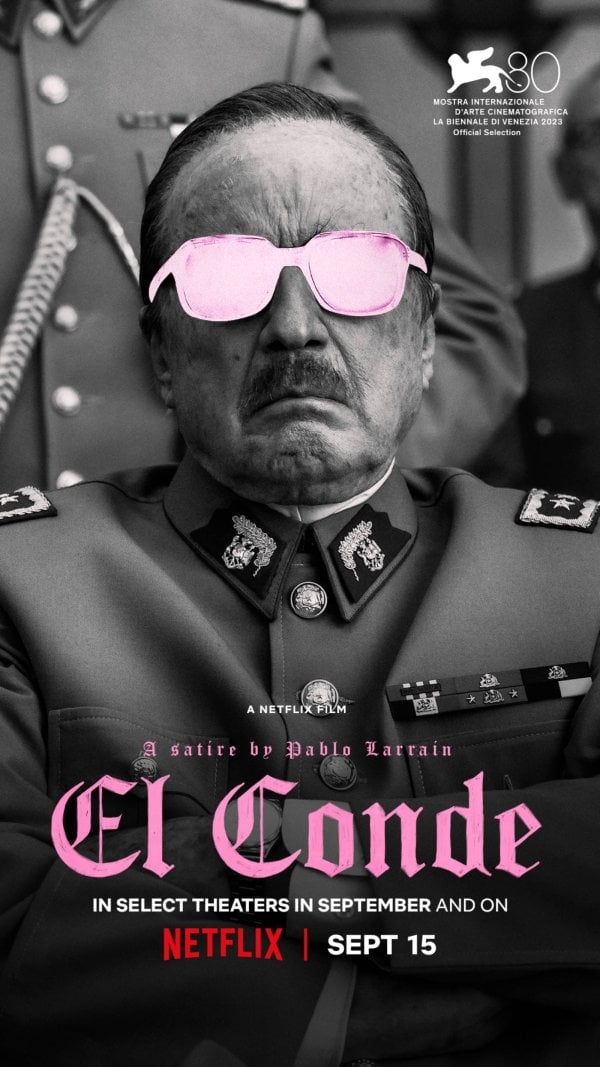

At the 80th Venice Film Festival Pablo Larraín presents a military Nosferatu, through a compelling black-and-white fantasy that blends horror, history and politics. We are thusly catapulted into the idea that “History is never fair.

”

The film is an immersion into an abstract reality — in terms of visuals and paradoxical narrative — but the heart of the story is exceptionally and disquietingly current. The March of Radetzky, that plays as the opening credits introduce the makers of the film in gothic characters, plunges audiences in the vampiresque atmosphere.

El Conde begins with a premise: during the French Revolution vampire Claude Pinoche (Clemente Rodríguez), a Paris-born orphan, joined Louis XVI’s army before deserting and passing off as a revolutionary. He enjoyed the taste of blood, even straight off the guillotine. Eventually he disappeared from history, attending his own funeral and fled to South America to make his appearance in Chile as Augusto Pinochet (Jaime Vadell).

His goal was to become a king. He came into power in 1973, leading the Chilean coup d’état. Pinochet sent the planes that bombarded the La Moneda palace, the seat of government where his defender would fall dead: President Salvador Allende. He became an invincible millionaire, chose a wife, Lucía Hiriat (Gloria Münchmeyer) and produced an abundant offspring: Luciana (Catalina Guerra), Mercedes (Amparo Noguera), Jacinta (Antonia Zegers), Aníbal (Marcial Tagle), Manuel (Diego Muñoz). In private he demanded to be called Count, i.e. El Conde.

However at this point in his life, after two hundred and fifty years of life, Pinochet — symbol of world fascism — is ready to die and decides to no longer ingest blood. He is facing an existential dilemma: it is unbearable for him to be considered a thief. Being seen as a murder is acceptable to him. In his eyes a soldier can kill, even if it’s by torture, making people disappear, and violating human rights. Life no longer has a purpose, not even with his wife or children. Only a nun, Carmencita (Paula Luchsinger) — who has to exorcise him and is sent to his house to help with accounting — triggers in Pinochet the desire to live again.

El Conde plays with the intricacy of relationships when money is involved. In fact, family affairs get more complicated as the Count’s faithful butler, Fyodor (Alfredo Castro) — a White Russian who killed Bolsheviks and was turned into a vampire by his master — engages himself in a romance with the lady of the house. Moreover, it is utterly amusing to observe the Pinochet siblings, now fully grown, who aren’t capable of making a living and are hesitantly waiting to inherit the bountiful assets of their father. Larraín takes this narrative device as an ingenious way to unfold all the assumed wealth of the dictator, from his numerous bank accounts all over the world (125 just in the US), to his apartments.

The film uses the grotesque to make a powerful political analysis, dissecting the entire world of the Chilean general. Larraín not only mocks the money-laundering structure of the family, but boldly takes the opportunity to expose how Augusto Pinochet remained free in his own country. The filmmaker’s intent is clear in conveying a warning: the system that allowed Pinochet to act the way he did must change in order to stop history from repeating itself.

Eventually the Chilean Commander fakes his own death, while he is still under investigation. The year is 2006 (Pinochet’s real death). But the vampire’s life does not end here, it actually continues in unison with someone who appears from his past, a woman. She is the British narrating voice, played by Stella Gonet, with whom Larraín had already worked on Spencer. She played none other than The Queen. The character she brings to life this time, allows Larraín to intellectually tear apart another controversial leader from the past. It’s not hard to guess who this woman from the United Kingdom could be.

The entire motion picture is exceptionally witty through its script, that Pablo Larraín wrote during the pandemic with Guillermo Calderón. The two men have also come up with feminist lines of dialogues, such as “If you want anything said, ask a man. If you want anything done, ask a woman.”

The visual rendering of the screenplay is remarkable. Ed Lachman’s high-end cinematography is utterly sumptuous, from the outdoor coastal views, to Santiago’s skyline seen from bird’s-eye view, as well as the oneiric moments of magical surrealism that occur in the Pinochet Mansion.

The entire cast is formidable, starting from the octogenarian Jaime Vadell.

Every shot made by Pablo Larraín is a gift. The images of frozen hearts being placed in blenders and drunk as energy smoothies is monstrously stupendous. There are moments of exceptional beauty when the Count and other vampires fly in the sky in search for fresh blood, that inevitably come across as an homage to Wings of Desire and to superheroes like Batman and Superman. Whilst the close-ups of the nun evoke Carl Theodor Dreyer’s silent film The Passion of Joan of Arc, also in consideration of an uncanny resemblance between Paula Luchsinger and Renée Jeanne Falconetti.

El Conde — that will be available on Netflix — is a potent metaphor of how evil never dies. Nefariousness endlessly transforms itself and finds new ways of survival, even amongst alleged dear ones. We are in fact told by the narrating voice how the Count turned his relatives into “heroes of greed”. At the end of the day, the carnage of the vampire/s is simply the physical manifestation of the corrupt intricacies of power, from the macro-angle of war, to the microcosm of family treason.

Final Grade: A