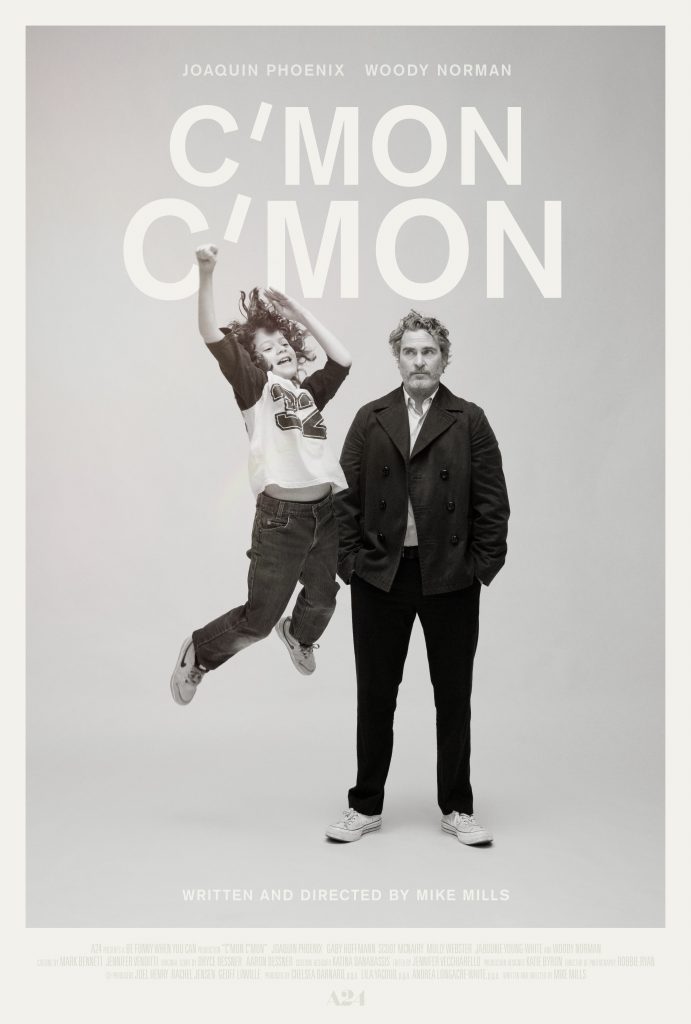

Synopsis : Johnny (Joaquin Phoenix) and his young nephew (Woody Norman) forge a tenuous but transformational relationship when they are unexpectedly thrown together in this delicate and deeply moving story about the connections between adults and children, the past and the future, from writer-director Mike Mills.

Production Notes

“When you think about the future, how do you imagine it will be?”

Mike Mills’ C’mon C’mon is an ode to the relationship between adults and children. It’s the story of a middle-aged man learning how to take care of a kid for the first time, set against a panorama of twenty-first century American cities and issues. It’s a story of an adult learning how to treat a child’s needs, worries, and joys with full respect; learning that they are different but not less than an adult’s. Johnny and Jesse are thrown together in a crisis moment, in their family and in the world. Their time together is a fleeting but transformative road trip that shifts how they see each other and how they see themselves. As they travel across the US, the ups and downs of this personal and public odyssey expands into an incandescent meditation on love, parenthood, memory, and how we keep going even though we have no idea what’s coming.

Joaquin Phoenix is Johnny, a hardworking radio journalist interviewing young people across the country about the future. Suddenly, his plans are upended by a family crisis when Johnny’s estranged sister (Gaby Hoffmann) needs him to step in as caretaker to her child, Jesse (Woody Norman). Johnny has lots of reasons to want to be there for his sister, but he has no experience with parenting a child—let alone one as smart and perceptive as Jesse.

It’s an emotionally loaded and often funny situation, which Mills turns into an intensely personal exploration of a man abruptly dropped into the deeply challenging and all-consuming world of parenting, with all its difficulties and wonders. Through the delightful times, sad times, hushed nights, and astonishing days, Johnny and Jesse find a tentative, yet transformative, trust. They push one another to hang tight through anxieties, to say what could not be said, to not let each other off the hook. And as they grow closer, this delicately contained story expands to touch on things far larger: our interconnectedness, what we owe to the future, what we remember, who we remember our past with, and how caring about one another becomes a way to heal when moving into the unknown.

Blending sharpness and tenderness in every element—with its mix of classic black & white photography, vivid immersions into American cities, deeply felt performances, and unscripted interviews with real young Americans—C’mon C’mon is Mills’ most cinematically playful and far-reaching story to date.

Mike Mills

Mike Mills has previously made a film inspired by his father (Beginners) and a film inspired by his mother (20th Century Women). In C’mon C’mon, he tells a story that is in some ways even closer to his lived experience: a story that excavates the rarely explored richness, but also the trickiness, of the adult-child relationship. At the same time, it surveys the most panoramic of themes: the idea that the future—in our personal lives and society at large—hinges on how we are able to talk to one another.

In 2014, Mills had a child with Miranda July. It was, for him, an instantly disorienting, then slowly revealing, transition, not unlike what Johnny experiences in C’mon C’mon, if not nearly as out of the blue. Mills knew he wanted to explore what was happening. But, in his typical way, his screenplay became a kind of cinematic auto-fiction: a candid, highly subjective self- accounting, one that takes place inside an imagined family and pulls from myriad influences around him—the movies, music, books, and people that inspire him, as well as the rhythms and textures of the culture we all live in right now.

“With C’mon C’mon, I wanted to play with opposing scales,” Mills says. “On the one hand the film is about the smallest of moments: giving a kid a bath, talking before bedtime. On the other, you’re traveling to big cities, hearing young people think out loud about their futures and the world’s future, so the intimate story is happening in the context of a far larger one. I often feel this same spectrum with my kid: our time together is so private, yet the biggest concerns of life are all there.”

Mills is fascinated by the pervasive links between the small, individual worlds we each inhabit and the big one we live in together. Writing about the most personal fears and intimate triumphs of parenting became entwined, for him, with documenting some of the vast complexity of young lives in the early twenty-first century America, as kids inherit the perils of our times from bewildered adults.

He hit on the road movie as an ideal structure for that mix. He could not help but think of a film he loves, Wim Wenders’ Alice in the Cities—the story of a German journalist who travels with a young girl after her mother doesn’t show up. “Early on, I thought of C’mon C’mon as almost a blues riff on Alice in the Cities,” says Mills, “because, like Wenders, I wanted to explore a child character as a creature with volition, concerns, and wants, and fears that are as valid as any adult’s.”

But the story soon took off in its own direction. Mills created the lead character of Johnny as a contemporary radio journalist—a man drawn to the art of listening, yet perhaps a bit out of time. Johnny’s occupation draws from Mills’ life—in 2014, he made a documentary for MoMA, A Mind Forever Voyaging Through Strange Seas Alone, in which Silicon Valley kids imagine what the future might look like technologically, environmentally, and personally. Johnny is making a similar radio series, traveling to different cities to talk to a broad spectrum of kids about their joys, fears, and hopes.

Johnny is clearly not a precise counterpart of Mills. He is insular, even willfully alone, estranged from his sister and split from longtime girlfriend. He doesn’t anticipate how caring for Jesse will shake up his life. But what Mills homes in on is how liberating it becomes for Johnny, how it lays bare certain things he had not seen about himself, and how healing it is to take care of this kid.

Mills chose to write about an uncle in part because it was a way to plunge an unsuspecting character literally overnight into the full-on intensity of parenting. “Johnny has to learn everything a parent learns but very, very fast,” he says. “As a father, I’ve found that you feel you’re constantly a novice, trying to keep up as things shift, and this was a way of recreating that confusion, that always being not quite ready for what’s happening. Of course, you don’t have to be a biological parent to experience that. You can be an uncle, an aunt, a teacher, or caretaker.”

Mills felt a pull to render a child’s closeness to an adult with all the complications, mixed motives, and bursts of wonder found in any major relationship—on both sides. “There’s a constantly interesting back-and-forth you have with a child that we rarely talk about,” Mills says. “It can be as light as playing but then it can be as deep as any adult relationship you’ve ever had.”

A constant theme in Mills’ work is memory, the things that persist, the things we miss, and that particular sinking fear that those elusive bolts of bliss can’t help but slip through our fingers. In C’mon C’mon, Johnny has the urgent sense that he needs to somehow capture what is happening with Jesse, even if all he has is their voices to do it.

As he wrote, Mills realized that ultimately the script would be reliant on two actors taking the roles to places he couldn’t foresee. That’s exactly what happened when Joaquin Phoenix and Woody Norman entered the picture. Suddenly, Mills was capturing the thrillingly immediate unfolding of a fellowship right there in the rooms and streets where they were shooting.

“What started as me trying to document and think about my life with my kid became equally a portrait of the relationship that developed between Joaquin and Woody,” Mills says. “I really tried to embrace that and let the camera capture that. And that’s when I get most excited as a filmmaker: when things feel that alive, unpredictable, surprising.”

Joaquin Phoenix/ Johnny

Casting Joaquin Phoenix as Johnny was not the typical process for Mills—it was instead a non-linear course of talking and exploring, then talking and exploring more. They acted out the script from front to back together, with Mills playing all the other parts aside from Johnny. “I’m not an actor and it was quite intimidating,” Mills laughs. “But Joaquin likes to experience things.”

For a long while, Mills forged ahead in the liminal zone of not being sure if Phoenix would take the role. But once he did, they found their instincts deeply aligned. “Joaquin doesn’t like when things feel like acting, and the more real things feel, the more he can play and be free,” Mills describes. “So, working with him became about constructing a situation wherein those feelings would naturally happen.” As they talked over every line, Phoenix became a confidante for Mills. “Joaquin has a super high radar for B.S., and he helped make me aware when anything felt fishy or expositional, and was just a great comrade and friend – always trying to figure out how we could make it better, more specific and real” On set, Mills often marveled at Phoenix’s emotional translucency, his ability to obliterate any barrier between his inner world and the camera. His work in the film felt different to Mills, certainly in stark opposition to the prickly and alienated loners he portrayed in The Master and Joker. “I think this is new turf for Joaquin,” comments Mills. “It can be the hardest kind of acting, when you’re not so much transforming into a fiction as reflecting, naturalistically, behaviors closer to who you are.”

Phoenix began by diving into Johnny’s art, the quiet, attentive interviews that he conducts around the country with Jesse in tow. “Radio is an almost nostalgic form, yet it interested me that Johnny is using radio to talk about the future to people who might not have a future,” Phoenix says.

He looked closely at the work of Studs Terkel, the pioneer of oral history who broke the broadcast mold by asking ordinary working people life’s biggest questions. Phoenix also listened to Scott Carrier, known for his pieces on NPR’s This American Life and All Things Considered, who began his career hitchhiking across America with a portable cassette recorder.

His primary influence, though, was fellow cast member Molly Webster—who plays Johnny’s colleague Roxanne, but in real-life is best known as a Senior Correspondent for NYC’s Radio Lab. “Molly has this ability where just being in a room with her you instantly feel comfortable. She has a genuine curiosity about others, and though she uses notes, she doesn’t reference them a lot because she’s really paying attention to what is being said,” Phoenix observes. “I learned a lot from that.”

After tagging along with Molly on some interviews in Los Angeles and learning to work the sound equipment, Phoenix began forging off on his own little ventures. “He wanted to understand how it works, and he got quite good at it,” Mills says. “Joaquin would much rather talk about other people than himself, and he followed his own path to figuring out how to connect with the kids.”

Once he was doing the actual interviews seen in the film, Phoenix says, “I just wanted to be as present as possible, to really listen to these kids and not shape what they said in any way. I was surprised at just how comfortable they were. Mike understood that young people are so rarely asked important questions, so they were willing to talk about anything and they were so bright, honest, and thoughtful. Part of Mike’s genius in the film is letting these unfiltered, real voices be heard.”

Phoenix became so absorbed in the role he asked Mills if he might start experimenting with making recordings of Johnny just talking in bed about his day with Jesse. This would ultimately add an unguarded sub-layer to the film. “You hear yourself differently when you hold a mic,” Phoenix notes. “It was an opportunity for Johnny to give voice to his most private thoughts.”

These introspective, nakedly confessional moments became a counterweight to the electricity and playfulness of the scenes between Phoenix and Norman. While Mills was writing as a father, Phoenix keyed into the idea of an uncle being almost— but not quite—a parental figure. “An uncle is more a friend,” he says. “But I think there’s something in the film that gets to the idea that we’re all responsible for children in terms of the world that we leave them and the actions we take, even if you’re not a parent. There’s also something very interesting about the idea that through our guardianship of children we can become more curious and open as people.”

Throughout, Phoenix was also observing Mills. While Johnny is not a direct replica, the influence is palpable. “I literally took his shoes from him for Johnny,” Phoenix laughs, “and the hair is inspired by him. Honestly, I think when a film is this personal, you’re always gleaning information from the writer. There’s a warmth and a sensitivity to Mills that informs the character. He’s someone who’s affected by what he sees in the world and feels things very strongly.”

That warmth and sensitivity was also something Phoenix felt in the way Johnny fits into the larger world of the film. “What stands out about Mike is how balanced and fair he is to each character,” Phoenix says. “Johnny could easily have been the most understood of the characters, but Mike is equally curious about all of them, and each person is fully alive and complex and has their own perspective.”

Woody Norman/ Jesse

The story of children in the movies has largely been one of innocence or frivolity. But there is an alternate history of films that see childhood not as a less complicated state of mind than adulthood, merely a different one. This is what Mills aimed for with Jesse, who, at age nine, leads a life that is certainly lit with enchantment and madcap fun, but one that can also be messy, infuriating, and as hard to manage as an adult’s. Jesse is, as his mother says, “a whole human being.” The burden of that was finding a young actor able to let the camera into his chaotic but deeply felt emotions. Jesse had to have just as many jagged edges as Johnny. Like Johnny, he’s a bit of a natural loner. Like Johnny, he’s driven by curiosity and all its perils. And like Johnny, he’s struggling with how to navigate their family—especially while his mother is busy helping his bi-polar father through a moment of crisis. “I wanted a child who wouldn’t only be charming, cute, and playful, but has multiple shadings,” Mills explains. “I remember early on, Joaquin kept saying to me, ‘Who’s the kid, man? You’re going to need an epic kid for this.’”

As Mills narrowed down the choices, Phoenix started having what were essentially improvised play sessions with leading contenders, including Norman. “It didn’t work right away, but there was something there, so we re-arranged Woody’s flight so he could come back the next day,” recalls Mills. “That’s when I asked Woody how he usually played with his brother, and he said wrestling. Joaquin started doing that big WWF-style wrestling character and they were just off.”

Norman grew up in the UK and came to the fore in the popular BBC series “Poldark.” He’d never carried a film before, but Mills sensed he had the strength. “In a great way, Woody’s not out at all to please you. Woody’s out to figure out what seems true and real to him. He’s confident but he’s not particularly reverential,” Mills muses, “which is a lot like Jesse.”

Most of all, Norman demonstrated a mystifying gift for immersing himself so intently into scenes he would do a vanishing act. “Sometimes I’d wonder, is Woody even aware there’s a camera there? He’s able, in a very unusual way, to dive deep and then stay there,” says Mills. “There are many times when Jesse’s not even talking to anyone and yet he’s extraordinarily present and vital.”

Norman related to Jesse, albeit not to his love of classical music, being a heavy metal fan himself. Mostly, he liked that Jesse is a typically modern kid who already has a lot on his mind. “My favorite thing about Jesse is that I see him as part child and part adult,” Norman explains. “He looks like a child, but he has some very adult thoughts, which kids do have.”

The script also offered him an emotional pendulum rare in roles for his age group. “In the span of a few minutes there is funny, sad, happy, and angry,” Norman observes. “And I think that’s what human relationships are really like.” Phoenix dubbed Norman “X-Factor” because he would do things so outside the lines. “He’s an outgoing, super smart, hysterically funny kid,” Phoenix describes. “He would just come up with things that were showstoppers, ad libs that felt so personal and lived-in and suggested a full history of the character.”

That sparked fresh reactions in Phoenix as well. “I’m always trying to get back to the kind of acting I did as a kid, because you’re so free, not self-conscious or really aware of having any particular persona. It was beautiful to witness that,” he says. “Woody was a guide in so many ways. Nothing would ever throw him off. For me, I’ve been doing it for so long it’s easy to get stuck into patterns. As far as he was concerned, there were no mistakes.”

For Norman, there was zero intimidation factor in working with Phoenix. He mainly saw an opportunity to learn and ran with it. “Joaquin taught me a lot,” he says, paying Phoenix perhaps the greatest compliment in saying, “I kind of think of Joaquin as someone my same age.”

A lot of Jesse’s physicality came spontaneously to Norman, including the miming that is part of his relational style. “It happened naturally,” recalls Mills, “so I started incorporating it. Woody is great at improvising with very little direction, as happened in the scene with Scoot McNairy as his dad, where Woody pantomimes an entire day with him and makes it into an unforgettable moment.”

Norman also was able to insert himself quite naturally into Jesse’s vivid, psychologically intricate fantasy life—including the game he plays where he pretends to be a bereaved little orphan. Mills liked evoking those parts of childhood that “are sometimes really strange if also completely normal,” he says. But the specifics of the orphan came from Aaron Dessner, who composed the score for C’mon C’mon with his twin brother Bryce. “When Aaron told me about his daughter doing that, my first reaction was wow, can I use that?” laughs Mills.

Sums up the filmmaker, “Woody and Joaquin developed a powerful bond – you see their own real relationship and closeness developing in real time. It wasn’t pretend and it led to moments like Woody suddenly putting his head on Joaquin’s stomach in New Orleans. I didn’t say to do that. They were just fully there.”

Gaby Hoffmann/ Viv

One of the most resonant characters in C’mon C’mon is one who, for the most part, is on the periphery of the action: Jesse’s mother and Johnny’s sister, Viv. Viv might not be with the pair physically, but her presence is constantly felt as she tries to knit them together from a distance.

Mills saw Viv as the embodiment of a quote used in the film from Jacqueline Rose’s book Mothers: An Essay on Cruelty and Love: “Mothers are the ultimate scapegoat for our personal and political failings, for everything that is wrong with the world, which becomes their task—unrealizable, of course—to repair.” He wanted to pay homage to a role that can be both marginalized and romanticized but is never less than essential. “My experience of being a father is that I’ve learned the most about the whole deal from my wife and from other moms I know,” he says.

Mills notes that the character, almost by necessity, contains elements of Miranda July. “There is a bit of Miranda in Viv in that she’s very smart and has her own independent life, but also has a deep, almost spiritual, relationship to motherhood that Johnny, as a man, is learning from.”

To fully evoke the mix of contradictions and insightfulness in the character, Mills turned to Gaby Hoffman, a three-time Emmy Award winner for her work in “Transparent” and “Girls.” He felt she was that rare person who could, largely through a series of faraway phone conversations, be the heartbeat of the movie.

“Gaby was always my first choice,” he says. “She’s such an intelligent, consistently surprising and authentic actor, and I always had the dream of putting her and Joaquin together. They look familial to begin with and I suspected they’d be from the same planet.”

That turned out to be the case—once they did meet. All agreed it could be interesting for the two to stay apart right up until they shot the scene in which Johnny rings Viv’s doorbell. This involved some amusing dodging during prep. “When Joaquin and I finally met, we did have this almost magic familiarity and brother-sister energy from the get-go,” Hoffman says. “We also have a similar approach to acting, which can’t really be described because it’s not exactly a process, but we both know it when it’s there. So much of who Viv is in the film became informed by what started to exist naturally between Joaquin and I.”

Phoenix adds, “Viv and Johnny are getting to know each other again, so Gaby and I let our relationship evolve without ever needing to define it. I was really impressed with her as an actor, and felt I’d known her a very long time. She’s unpretentious, self-deprecating, and adventurous.”

Hoffman recalls the unmistakable love for Viv that Mills demonstrated when they first met, which enticed her. “The way Mike talked about Viv and about the intricacies of her relationships with her son, her husband and her brother was dynamic, very moving and clearly coming from a place of profound feeling in him,” she says. “As a parent, I could see how much of Mike went into the story and I wanted to be a part of that.”

Hoffman also latched onto Mills’ fascination with all the clashing expectations placed onto mothers and the way real women try to navigate them. “Viv is 100% devoted to her child, but at the same time, she’s committed to living her own life— and making those two things work. She doesn’t believe her entire person has to be subsumed by motherhood,” Hoffman says. “Viv feels she can be an intellectual, a good partner, a sister, and absolutely a mother—but not in a sacrificial way. And I think you get a sense that this is what leads her to how she’s raising Jesse: as someone who thinks about what it means to be a person in the world.”

Watching her brother attempt to do the same is exhilarating for Viv, especially because she realizes Johnny needs it as much as Jesse. “Viv understands well before Johnny that this time with Jesse, in all its trials and all its joys, is going to be a huge gift to him,” Hoffman observes.

The family’s renewed ability to talk flows into the larger concept of young people talking openly about the world and lives that lie in front of them. “For me, the film is really about how we take care of one another, whether in our nuclear family or our human family,” sums up Hoffman. “There’s this question that hangs over the story of who’s going to take care of these kids who are our future? How are we going to take care of one another, whether we are 9 or 50?”

Joaquin Phoenix

Joaquin Phoenix has appeared as an actor in To Die For (1995), Gladiator (2000), Walk the Line (2005), The Master (2012), The Immigrant (2013), Her (2013), Inherent Vice (2014), You Were Never Really Here (2017), and Joker (2019).

Gaby Hoffmann

Gaby Hoffmann is known for her role on the critically acclaimed Amazon show “Transparent”, for which she received Emmy nominations in 2015 and 2016 for Outstanding Supporting Actress in a Comedy. Gaby directed an episode of “Transparent” in season 4. Gaby has acted in dozens of films, on stage, and guest starred on “Louie” (FX), and “Girls” (HBO) for which Gaby received an Emmy nomination in 2015 for Outstanding Guest Actress in a Comedy Series (“Girls”).

Woody Norman

UK based actor Woody Norman had an incredible experience working with Joaquin Phoenix in the A24 film C’mon C’mon, written and directed by Mike Mills. Norman is currently filming Amblin’s Last Voyage of the Demeter, directed by Andre Øvredal, where he shares the screen with Corey Hawkins. He will be seen in 2022 starring in the Lionsgate thriller Cobweb opposite Lizzy Caplan and Antony Starr. Other film credits include Alexander Jeremy’s The Space Man with Colin Farrell, Karl Golden’s Bruno, Alfonso Gomez-Rejon’s The Current War, where he played Benedict Cumberbatch’s son and Justin Molotnikov’s The Small Hand. Woody recurred on BBC One’s “Poldark,” “Troy: Fall Of A City,” “The War Of The Worlds,” and “Les Miserables.” He was also seen in Starz’s “The White Princess” opposite Jodie Comer and ITV’s “Peter and Wendy.”

Molly Webster

“Molly Webster is an award-winning writer and performer who lives in Brooklyn. She is the Senior Correspondent at Radiolab, the Peabody-winning radio documentary program. She developed, produced, and hosted the critically- acclaimed podcast series Gonads, a romp through sex ed you didn’t know you didn’t know. Molly has adapted her audio and written work for the stage, performing in theatres from the Brooklyn Academy of Music to the TED Mainstage. Throughout her career, she has collaborated with directors, musicians, sound designers, and visual artists. She is the author of the forthcoming children’s book Little Black Hole, to be published by Philomel, and is working on an untitled documentary. C’mon, C’mon is her film debut.”

Jaboukie Young-White

Jaboukie Young-White is a comedian, writer and filmmaker from Chicago who

is known for his role as a correspondent on “The Daily Show With Trevor Noah.” Named one of Variety’s 10 Comics to Watch at the 2018 Just for Laughs Montreal Comedy Festival, Jaboukie has performed stand up twice on “The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon” and recently debuted his half-hour for “Comedy Central Stand-Up Presents.” Jaboukie can be seen in the last season of HBO’s “Crashing,” the Sony feature Rough Night directed by Lucia Aniello, the Netflix feature Set It Up directed by Claire Scanlon, and in Jennifer Kaytin Robinson’s feature Someone Great also on Netflix. Previously, Jaboukie was a staff writer on Netflix’s “American Vandal” and the animated series “Big Mouth.” Coming up, you can see Jaboukie in the A24 produced Mike Mills feature C’mon C’mon opposite Joaquin Phoenix, and as the lead in the independent rom com film Dating & New York, which premiered at the 2021 Tribeca Film Festival and will be released by IFC Films this fall. Jaboukie will recur in the upcoming Hulu series “Only Murders in the Building,” and the upcoming HBO Max series “Rap Shit,” produce by Issa Rae. Jaboukie also voices the lead role of ‘Truman’ in the upcoming animated series “Fairfax” on Amazon. Jaboukie has over 886k followers on Twitter @jaboukie