@Courtesy of HBO

Runtime : 1h 57m

©Courtesy of HBO

Press Conference With Directors Charlotte Kaufman and Andrew Jarecki

Q: When you were first starting out with the project, what was it before it took the form that we now see?

Andrew Jarecki: When we first went into the prison, we didn’t know what we were going to experience. It was pretty rare to have access because prisons in the United States are black sites. You drive by them on the highway, you see a little metal sign that says Correctional Institution. A lot of people feel like: “I don’t really know what’s happening there, but it’s probably not terrible and I’ll feel better if I drive by and I don’t think too much about it”. They sometimes call it ‘the belly of the beast’, we were able to talk directly with people who were incarcerated there.

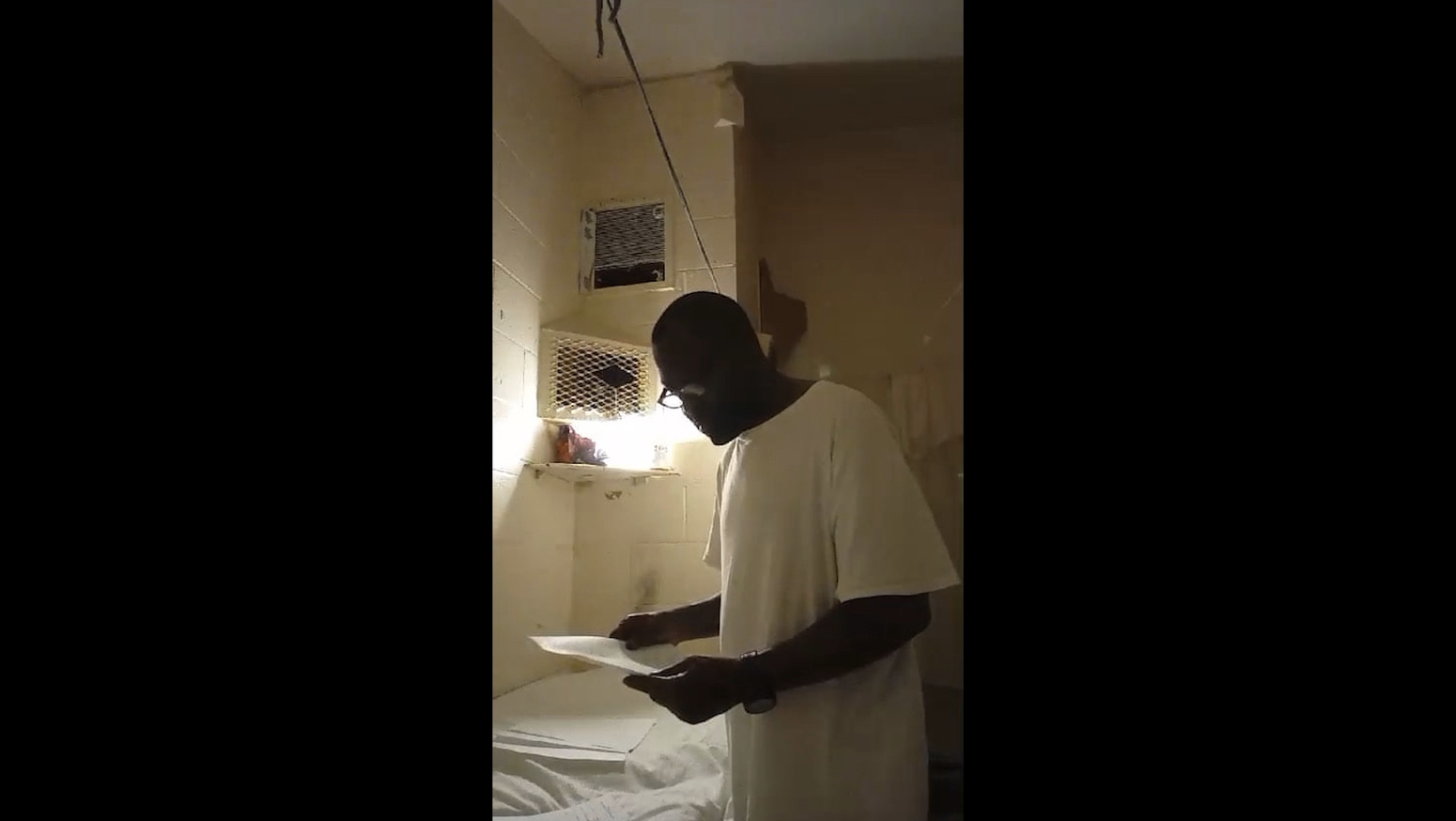

We didn’t know what was going to come out. We didn’t know at that time that there was such a proliferation of contraband cell phones in the prison. When we first spoke to people, they started to give us a sense of what was really happening in the areas that we were not allowed to see. After we left, the men started reaching out and we realized that there were these incredible leaders on the inside who were extraordinarily thoughtful about what they were going through. They had been organizing a non-violent protest movement for more than a decade, and were able to talk to us about it, even help us investigate what was happening in the prison. In some way they became part of the investigative team when we were researching what was happening.

Charlotte Kaufman: After our first visits to Alabama, we saw an institution in free fall. That’s what compelled us to keep investigating. We’re investigators and that’s what we do. So, we felt compelled to keep looking and then once we were able to speak with these incredible men on the inside, all of a sudden this story emerged and took a new form.

Q: Can you speak about what it was like to make this documentary that takes such a unique form because it shares authorship with so many of its subjects?

Charlotte Kaufman: It was a great honor to be able to have this uninterrupted dialog with Melvin Ray, Robert Earl Council and many others who are not in the film, but who provided very important context for our understanding of what was happening inside Alabama’s prisons. If you want to communicate with people who are incarcerated, you’re limited by the prison system which limits phone calls to 15 minutes at a time, which will try to say they must approve whom the press can speak to. In this case, because of the particular circumstances in Alabama, we were able to have uninterrupted dialog and really go deep. That created the opportunity to learn about these men and the life they’re living, the circumstances inside the prisons in a much deeper, more meaningful way. That is what allowed us to actually be, to collaborate with them, on a deeper level.

Andrew Jarecki: It’s so unusual to have direct access to people living in that condition. As you see happening in America right now, there’s a movement more in the direction of more incarceration, worse incarceration. Incarceration is a huge part of what we’re seeing in our lives right now. For the most part journalists are not permitted inside prisons. In Alabama they have almost 50,000 in prison, people who are essentially not allowed to talk about their circumstances. That’s disturbing. We’re a democracy, we ought to have access to what’s going on.

There are two million people in the United States who are incarcerated, 80 billion dollars a year are spent on this system, and we know so little about it. It leaves room for all kinds of human rights abuses, a real crisis in Alabama. But Alabama is the lens through which we can understand incarceration and what happens when you have unchecked, secretive incarceration. It’s not good when you let people do whatever they want to other people, there is no constitutional protection because we’re not doing a very good job right now in the United States thinking about constitutional protections. They are very limited. Essentially, you’d have to prove that something is cruel and inhumane in order for the Constitution to kick in. Then the federal government is allowed to intervene. That’s a big question mark right now because the effort is not to look into these institutions, to maintain the secrecy and increase it.

Q: What advice would both of you give to those that want to tell important stories that could put you personally in the spotlight?

Charlotte Kaufman: What’s more important in this situation is the men on the inside who have chosen to be in the spotlight. Robert Earl Council, Melvin Ray, Raoul Poole. Since 2013 when cell phones first came into the prison system, they recognized the power of the technology to transcend the secrecy of prisons and to actually be able to share with the world what’s happening to them. What’s at stake when you lock people up with no accountability and secrecy. They made the decision about whether they would actually show their face as they shared this information, participate in a film like this or participate in journalism prior to meeting us.

As Melvin Ray, one of our subjects said, ‘it’s more dangerous for us when the cameras go off’. I would say for filmmakers working with subjects in risky situations, you have to keep the dialog open. You have to continue to revisit the stakes and maintain transparency in the relationship. Fortunately for us, there’s an organization called One for Justice that has organized a group of lawyers who are ready to respond to any retaliation, conduct site visits at the prison frequently to let the administration know that people are watching, that they have support, that the public cares about what’s going to happen to them.

@Courtesy of HBO

@Courtesy of HBO

Q: What kind of strain does it place on you as filmmakers to have to enter into this almost negotiation of being part of that danger?

Charlotte Kaufman: It’s obviously a huge responsibility for us. We’ve been concerned for their safety since we began a dialogue with them six years ago. We continue to be concerned for their safety. We’re concerned for the safety of everybody inside Alabama’s prisons. Whether you’re a whistleblower or not: you are in danger. In addition to all the deaths you see investigated in the film, we’ve also tracked every single death since the beginning of our filmmaking, there are over 1,300 people that have died. We’re able to confirm around half of those from causes like murder, overdose, suicide. Being in the facility is dangerous for everybody. As filmmakers, that is a very uneasy thing to contend with, the best we can do is to have transparency with our participants. Try to provide support as the film comes out, or organize support as film comes out.

Andrew Jarecki: Providing an incredibly brave and valuable service to all the other people that are incarcerated, not just in Alabama, but elsewhere. Somebody’s got to do it. Somebody’s got to stand up and say, ‘I’m a person that’s willing to take the risk of showing what it’s like in here, even though I have been retaliated against in the past,’ and you see that in the film. In Alabama, they would like these men to be dead, and they’ve tried to kill them.

The level of bravery that we see in their consistently being willing to speak out, whether it’s through cell phones or any other action they can take through non-violent means, is breathtaking for us. Everybody on the film team felt like this wasn’t a traditional film where you were going to go home at six o’clock. Everybody realized that if a call was coming in from Alabama at midnight or at two o’ clock in the morning, you had to be there for it. There was no alternative. They had been getting the word out as best they could. They didn’t have the machinery of a documentary crew. They didn’t have the distribution of an HBO, which can get this kind of story out to the entire world.

Charlotte Kaufman: As filmmakers, it is a surreal experience when you have to sit back and contemplate whether the risk of someone speaking out about taxpayer institutions could be bodily harm. That is a constant question that you’re asking yourself. Just speaking the truth could lead to bodily harm in American taxpayer institutions.

Q: How do you see the role of documentary makers in the world of politics at the moment and what are the limits?

Charlotte Kaufman: The role of documentary filmmakers is to pay service to the truth. We are seeking the truth, we’re looking at ways to put it together in formats that speak to the human experience and the human way of processing the truth, which is stories and characters. After that, it’s up to the public to make sense of the truth, if they feel inspired by it and they want to take action. How can politicians and lawmakers make the right decisions if they don’t have the full scope of the truth in front of them?

Andrew Jarecki: There is a generalized anesthesia that happens around issues that are very thorny like prison. They know terrible things are happening in their prisons, they know that in Alabama, they know in New York where there have been horrible events at Rikers, in California where they had to release large numbers of people because they were so overcrowded. I’m not sure that the individual government members are informed about it. That’s a willful blindness, we always ask them when we’re interviewing the attorney general or somebody: “Do you visit the prisons?” And they usually give a very unconvincing answer. They’re probably getting the same tour that they were trying to give us, which is: “Here’s the yard, there are men smiling, we’re feeding them barbecue”. They are also not allowed to look in. They’ll find an area of the prison that is very cleaned up and looks civilized, and they won’t show you the rest of it.

Charlotte Kaufman: Crime is becoming a very politicized issue, the next election cycle there’s a new tough on crime rhetoric, concern with crime and safety, security of communities. Everyone agrees that safety and security in communities is very important. The thing that documentary can do, and hopefully our film does, is it will help people question whether the solutions that we have put forth for crime, for safety, are actually working, or if perhaps they’re doing the opposite of correcting, they’re creating more harm. What you see in the film is a prison system that represents many prison systems across America: not one that is correcting BUT causing more harm, deepening many of the issues that bring people to prison or might have led them to commit crime in the first place. If we can’t see the full scope of a problem, if we can’t see what’s actually happening in the prisons and how it might be contributing to the larger issue of crime, then how could we ever solve it?

Q: The prison system is an industry. How can change a system if someone is making money out of it?

Charlotte Kaufman: Unpaid labor, slave labor is a big part of the film and it’s a big focus of the work of Melvin Ray and Robert Earl Counsel and many other men inside. When there is a profit incentive to keep this whole system going, it’s much harder to fight it. The profit isn’t just unpaid labor, it’s also all of the construction companies and the people who run the commissary and the telephone company. Everything has been outsourced for private companies that can make a profit off of the destruction of human lives. Another aspect of unpaid labor is that it leaves people destitute when they come out of prison. It is an economy of deprivation. If you were able to make some money while you were incarcerated, then you might be prepared when you come out to set yourself up. Instead, they give them $20 and a bus ride.

Andrew Jarecki: There’s $450 millions a year in free labor that this state benefits from. The prisoners are actually leased out to private companies. These guys are sent out to work at McDonald’s, to work at the Budweiser distributor, to work at the chicken plant, to work at Burger King, and the state profits from that. They work in the governor’s mansion. They do construction projects. They’re considered an enormous source of economic benefit for the state. The big corporations will say: “We’re helping these poor incarcerated men to develop skills”. But the reality is they’re getting workers who can’t unionize.

There are actually rules in Alabama that if you go out on a work release program, it’s against the rules to speak. It’s against rules to talk to other people you’re working with. One of the most chilling things that we learned is that if you’re considered safe enough to work in the community, if you are considered somebody who hasn’t had any disciplinaries, somebody who’s considered the best of the prisoners, you are statistically less likely to be paroled than the people at the next highest custody level. The more valuable you are as a laborer, the less likely you are to be paroled. It’s a very disturbing, very disturbing fact.

@Courtesy of HBO

@Courtesy of HBO

Q: Which kind of scrutiny a correction officer must go through in order to be hired in an Alabama prison? Is it different from Alabama to other states in the United States?

Charlotte Kaufman: In Alabama there’s no mental health screening for correctional officers. That’s something that many officers we’ve spoken to bring up. They are very sensitive to mental health: the job is very difficult on your mental health but they do not assess it. Nor do they check in to see how people are doing, whether they might have PTSD from being surrounded by death and violence and brutality every day. When you develop PTSD from that, you’re going to have a trigger response, you’re going to respond with more force, less rationality, you’re not going to be able to calm yourself down. That’s one very significant thing to be aware of. And then, there is a big staffing crisis in the prison. They are trying to recruit as broadly as possible. I think at the moment what’s required is a high school diploma and some physical training and tests.

Andrew Jarecki: They need to hire everybody that shows up because they’re so understaffed. When you get to a certain staffing level, you can’t recruit people anymore because everybody hears that this is a terrible job. So they try to come out and say: “We’re giving you an incentive, we’re going to increase your pay”. But at the end of the day, the system is very sick. The average corrections officer is making $38,000 before they start selling drugs or contraband cell phones. And 38,000 becomes like 70,000 if you can sell drugs. Now you have people who are theoretically there to care for people, wards of the State. You’re in charge now.

The prison’s in charge of their medical care. The prison is in charge of their mental health. The prison is in charge of literally everything in their lives. They can’t find people who are willing to take on that responsibility. Often they find people who are likely to be violent, who are willing to sell drugs, who are willing to do things that will make it much, much harder for those men to ever recover. And then they say: “Recidivism is so high!” It turns out when people have no resources, they sometimes try to steal food. Women are in prison because they took baby formula or diapers. Most of these people are who we would be if we had absolutely no choice and had to take care of our child or our family.

Q: In the process of making this documentary, did it in any way challenge or enlighten your preconceptions of incarceration itself as a whole, not just the most extreme version of it that we see in the film?

Charlotte Kaufman: During the making of this film, we have seen certain officers be charged with abuse and be sentenced. So you think that there is justice and that there will be some level of accountability.The punishment of these officers or at least them going through the court system is important because it sets the message for everybody else that this is not acceptable. That will advance more safety in the prisons and will let people know that no, you do not have the green light to just beat up whoever you want. There will be consequences, but whether they deserve to be in a system where now they’re going to also be brutalized and tortured, I would disagree with that.

Andrew Jarecki: If the system gets rethought in certain ways, the purpose of this would be to rehabilitate people. Instead It’s a race to the bottom. There’s some people in society who end up in a desperate situation or commit crimes or are mentally ill or have drug addiction. You’d like to be able to bring them into an environment where they can get better, because they’re going to be our neighbors. These men inside, especially Robert Earl Council and Melvin Ray and their participants in their nonviolent protest movement, are really inspiring leaders. You know, they are rehabilitated. They have on their own, without the help of the state, learned the law, begun to be able to help other people get out of the system, and they’re taking a huge risk to do that. It’s so incredible to see the bravery of these guys. t’d be such an amazing country if people had that kind of ability to lead, to pursue nonviolence. That’s the most inspiring thing about the film for us.

Charlotte Kaufman: As Andrew mentioned before, we spend $80 billion on prisons in America every year, and yet we never ask: “Are they even doing what we think they should be doing? Are they achieving the mandate that we’ve placed on them?” This film shows that in many ways it’s not, and perhaps we should be interrogating how that $80 billions is being used. Perhaps it can be used in other ways, upstream to prevent people from coming to prison in the first place, because certainly what’s happening in the facilities is only adding to this cycle of harm. That should be interrogated.

Andrew Jarecki: A lot of people are making a lot of money by keeping people locked up. Unfortunately, there’s a downside to it, which is you’re locking up large sections of the population. In Alabama and other places the incarcerated men do the vast majority of the work. The problem is that when you make a whole labor market out of it, the public doesn’t realize that they’re walking down the street and seeing people working at McDonald’s who just got out of a van and are going to be told they can’t speak all day. The penalty for not working is often death. In other words, if you refuse to go to your job, they can give you disciplinaries, they can extend your sentence, they can move you to a more dangerous facility, they can put you in solitary confinement, which is absolutely done all the time. Ultimately, it’s on pain or death that they’re working. It’s not very different from any other kind of forced labor.

Charlotte Kaufman: It can also give you a disciplinary that will, when you go up for parole, you’re not going to get parole. It’s your choosing between working or your freedom in many ways.

@Courtesy of HBO

@Courtesy of HBO

If you like the interview, share your thoughts below!

Check out more of Adriano’s articles.

Here’s the trailer for The Alabama Solution: