Hirokazu Kore-eda directs his first Netflix series, adapting for the screen the comic that won the 65th Shogakukan Manga Award and is a best-seller with over 2.7 million copies sold. The Japanese filmmaker rewrites the manga series by Aiko Koyama, Maiko-san Chi no Makanai-san, published by Shogakukan, shaping it into a tender coming-of-age story.

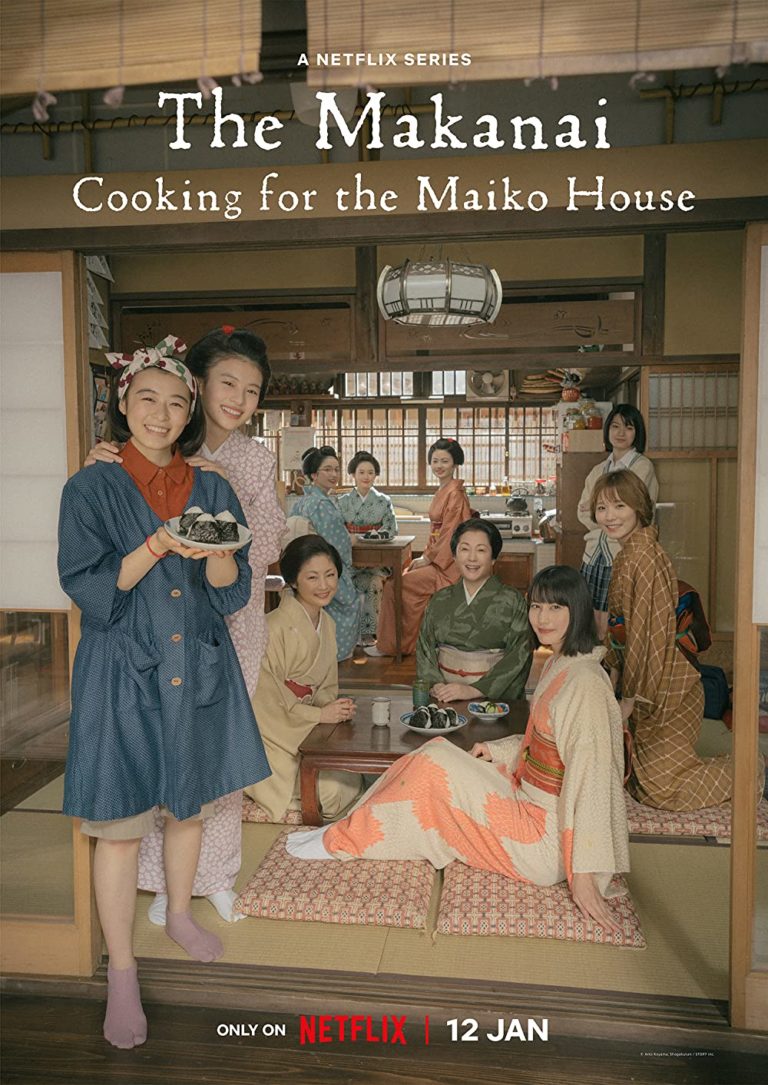

The Makanai: Cooking For The Maiko House is a series whose narrative is conducted in tandem, as we follow the growth of Kiyo Nozuki (Nana Mori) and Sumire Herai (Natsuki Deguchi). The two teenage girls from Aomori, instead of going to high school, decide to go to Kyoto to become Maikos (apprentice geishas). From there on forth a wondrous world is revealed to the public, that unveils the authentic customs of the land of the rising sun and the universal values of the unconventional families that the director of Shoplifters and Broker is capable of portraying.

The value of friendship is celebrated in all its glory. Kiyo and Sumire have seen the same things growing up in the Northern part of the Tōhoku region.

They are so close they understand each other at a glance, without using words. They have the type of attachment that shows how friends are the family we choose. The two sixteen year old girls are more than sisters, they have a pure understanding and earnest care for each other.

This is something that is well understood by Kiyo’s grandmother (Kayoko Shiraishi), who supports their Kyoto-adventure and their peer-friend, the handsome and chivalrous Kenta Nakanowatari (Kairi Jyo). He is the one who, as a baseball player, describes their kinship as “a good battery,” that is a pitcher and catcher who work well in unison.

Sumire shares with Kiyo a selfless nature and an adamant dedication to others, in fact she admits that before aspiring to become a Maiko she wanted to be a doctor. As initial apprentices the two girls are plunged in a dimension where they have to revolutionise their previous understanding of the world. No mobile phones are allowed and they have to attend courses that are very different than what they were studying in middle school, like the art of Mai dance. Even the lingo differs, starting from the greetings, because they apprehend that you don’t say “It’s nice to meet you,” but you say, “I ask for your cooperation.”

The initial apprentice Maikos train to be able one day to entertain an Ozashiki, the geisha gathering that features a traditional banquet followed by a Geiko performance. However, as someone who fell in love with a Japanese woman once said, “life is what happens to you while you are busy making other plans.” [John Lennon who married Yoko Ono]. This is exactly what happens to Kiyo who planned to become a Maiko, but life leads her elsewhere. One day an accident occurs in the kitchen and Kiyo offers to cook. This serendipitous occasion marks the beginning of her new life as the Makanai of the Maiko House, the person in charge of cooking meals.

Sumire’s stoic dedication and “once-in-a-century-talent” lead her to accomplish her dream of becoming a Maiko, working under the name of Momohana. She has her hair fixed in the traditional fashion and gets acquainted with sleeping with the taka-makura hair-pillow. But nothing changes between her and Kiyo, there is never a moment of jealousy, rivalry or friction. Their bond persists, they remain the closest of friends and rely on each other.

The family-like relationships in The Makanai: Cooking For The Maiko House extend also to other characters in the series who populate the ‘Saku’ household. The Mothers of the Ochaya geisha house — Ms. Azusa (Takako Tokiwa) and Ms. Chiyo (Keiko Matsuzaka) — are the ones who benignantly explain the new lifestyle that awaits Kiyo, Sumire and the other young girls who aspire to become geishas in the future. There is a sense of camaraderie that develops between the Aomori teens and Tsurukoma (Momoko Fukuchi), Kikuno (Kotoko Wakayanagi), and Kotono (Kotoko Wakayanagi). More women populate this uncustomary family. There is Ryoko (Aju Makita), the daughter of Mother Azusa, and two very different types of geishas who mentor the initial apprentice Maikos. Momoko (Ai Hashimoto) is more traditional and sulky, but exceptionally sophisticated; whereas Yoshino (Mayu Matsuoka) is a loose canon with her tomboyish and unconventional ways.

Even the men that revolve around this matriarchal society are extremely amiable and we have many examples. There are the two gentlemen who take care of dressing the Maikos and Geikos; there is Momoko’s sweetheart, who asks her to join him in Tokyo and live in the Jiyu Gakuen Myonichikan Building designed by the illustrious architect Frank Lloyd Wright. There is Ms. Azusa’s wooer, Masahiro Tanabe (Arata Iura), who bashfully aspires to marry her one day; there is Yoshino’s husband; there is Ms. Chiyo’s first love; there is Mr. Ren (Lily Franky), the bartender who suffers from unrequited love. They all exemplify sympathetic and kindhearted men.

In The Makanai: Cooking For The Maiko House love is demonstrated in all its facets. For instance, Kiyo’s shy and humble nature expresses it through the gastronomical art. If food can be the most nurturing gift you can offer, Kiyo masters it with all her heart, making specific treats for the guests of the Maiko house, above all for her best friend Sumire. She becomes the ‘Otafuku’, the Goddess of Mirth. This popular image in Japanese culture can be found in the figure of a statue placed on top of the roof tiles of front doors, to ward off evil. Kiyo, as the angel at the hearth, involuntarily and unexpectedly, becomes the glue who keeps the entire household together. Every dish is an act of love, in the making and in the thought that went into it. Whether it is pudding for Tsurukoma, nabekko dumpling soup for a farewell, bread crust rusks and deep-fried oysters for her best friend’s ceremony, Kiyo always expresses her feelings through her culinary talent. Thus, food becomes a language that runs in parallel to the entire narrative that traverses an entire year.

In Japan, seasonality influences all fields, including the style of cooking. For instance, New Year’s celebrations are feasted with ozoni soup and oseichi treats, and most importantly with the Toshikoshi soba. The series also portrays the regional variances, like the vegetables that can be found only in Kyoto: manganji peppers, kujo leek, horikawa burdock. Or the different eating customs: when people are ill in Aomori they are given rice porridge, whereas in Kyoto they make udon that isn’t dark. This detail gives way to another demonstration of how food is the way to the heart, when Kiyo ventures into making it from scratch, embarking on a grocery hunt to find bonito flakes and rausu kelp.

Most importantly, The Makanai: Cooking For The Maiko House provides a glimpse in the rich Japanese culture and some traditions that are often misunderstood and simplified. A clear example is given when Sumire’s father, a respectable doctor, goes to Saku to take his daughter back home, because he doesn’t want her involved in a nightlife business. But by watching how her daily routine is organised, he soon realises she is training to become a performer that can be compared to a kabuki actor. Maikos and Geikas are inheritors of a traditional performing art. Throughout the series we also learn about the different types of Mai that can be enacted by a Geika. For instance, Momoko performs a ‘Kurokami’ that portrays a woman thinking of her lover who fails to come to her side, making the loneliness of her heart grow each night. The theatricality of this profession is expounded in many ways. The women who walk on the traditional Japanese sandals known as Jobi, covered by the Tabi socks have a very elaborate dressing ritual. Spectators have the chance to observe the layering of a Kimono: from the Nagajuban to the Eri-shin, passing from the Obi-ita to the Obi-makura, all held together by the obi and the Obijime, adorned with the Obiage. Seasons affect also the fashion accessories of Maikos, who wear the Maki comb, whereas in winter they use the Tsumami.

The series also shows the mundane activities of this community. These can include going to the Yasaka Shrine to pray, gathering raffle tickets to win a prize, or being so lucky to ride the Four-Leaf Clover Taxi and receive the commemorative card. Amusing moments are shared, like the preparation of the Obake event, where Mai performances are held between all geisha houses. In this circumstance Momoko finds an ingenious way to develop the Saku version, inspired by George A. Romero’s Night Of The Living Dead. She embeds Noh techniques in the performance, as the Maiko-zombies glide their feet to reminisce the undead. There are also philosophical reflections that ponder upon the complexity of emotions. It is particularly meaningful when a Geiko explains to a Maiko how the complexity of love primarily requires finding one’s calling before projecting feelings to another person: “Make sure to fall in real love. Just because you’re together doesn’t mean it’s real love. And if your love is unrequited that doesn’t mean it’s not real. You don’t just fall in love with people. First fall in love with performing. It’s not too late to fall in love with someone after that.”

The Makanai: Cooking For The Maiko House shows how collaboration is the key to a happy life, in every stage of our existence. There is no need to trample someone else’s dream to accomplish your own. Everything can coexist if it is amalgamated with love, just like Kiyo’s and Surime’s different destinies, just like the ingredients of the Makanai’s dishes, just like the gestures in the performance of a Maiko.

This series is an awe-inspiring contemporary fable, that doesn’t fail to nurture the soul and taste-buds, one episode at a time. Through the art form of the Mai performance, The Makanai: Cooking For The Maiko House bequeaths to its viewers the importance of seizing the day. Every stage performance, just like many life situations, constitutes a unique and unrepeatable moment. Each Mai is different every time, and those who watch it will share an instant that will never happen again.

They all experience an “Ichi-go ichi-e moment,” that they can treasure as something that occurs once in a lifetime.

Final Grade: A

[…] Spagnoli Garbadi from Cinema Daily refers to the show as a “tender coming-of-age story” that “doesn’t fail to nurture the […]