Aftersun

Synopsis : At a fading vacation resort, 11-year-old Sophie treasures rare time together with her loving and idealistic father, Calum (Paul Mescal). As a world of adolescence creeps into view, beyond her eye Calum struggles under the weight of life outside of fatherhood. Twenty years later, Sophie’s tender recollections of their last holiday become a powerful and heartrending portrait of their relationship, as she tries to reconcile the father she knew with the man she didn’t, in Charlotte Wells’ superb and searingly emotional debut film.

Rating: R (Brief Sexual Material|Some Language)

Genre: Drama

Original Language: English (United Kingdom)

Director: Charlotte Wells

Producer: Mark Ceryak, Amy Jackson, Barry Jenkins, Adele Romanski

Writer: Charlotte Wells

Release Date (Theaters): Oct 21, 2022 Limited

Runtime: 1h 41m

Distributor: A24

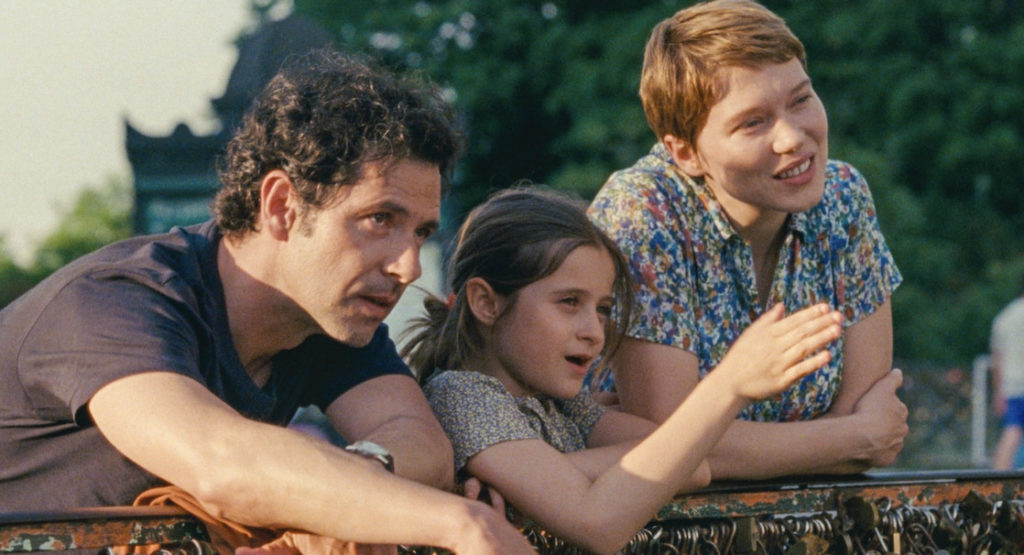

One Fine Morning

Synopsis : Sandra, a young mother who raises her daughter alone, pays regular visits to her sick father. While she and her family fight tooth and nail to get him the care he requires, Sandra reconnects with Clément, a friend she hasn’t seen in a while. Although he is in a relationship, the two begin a passionate affair.

Q: We decided to put your films together because they speak to each other in a lot of ways. They have similarities, but in many ways are also perfect opposites. One thing was the titles: “One Fine Morning” and “Aftersun” presents some kind of conversation between those titles. Can you talk about the titles and their relationship to the films?

MHL: I’m not really sure about the rational reasons for that title. It’s more of a poetic idea, I guess. There’s an idea of clarity and of light in that title that gave me direction somehow. I always feel like the titles are helping me to find the direction when I start writing. The title “One Fine Morning” sounds like the beginning of a story you want to tell, almost like a fairy tale, the stories you tell to kids, and that relates the film to childhood. I think that’s part of why I picked this title.

CW: I don’t know that I have a good answer to this. It was always “Aftersun.” I find titles either very easy or impossibly hard, and it was just always “Aftersun.” I’ve heard or read people speculate as to why, or analyze meaning in relation to the film, and I’m very interested in reading those. I don’t disagree, but there’s no conscious decision. “Aftersun” in the UK is a lotion, like an aloe vera, what you put on your skin when you get burned.

Q: So it’s like a sunscreen?

CW: It’s like [if] you didn’t put sunscreen on. So it’s after the sun. That is what I had in mind when I chose the word. I was thinking about Aftersun, the product, but it can be interpreted a lot of different ways, and I don’t like to do that interpreting myself.

Q: Both of you have talked about the autobiographical nature of these stories. Charlotte, in the press notes you described this film as emotionally autobiographical — it’s fiction but was inspired by some emotional truths for you. And Mia, you said something that was very striking: you’re always trying to make films representing life as it is, but also make films that help you to live, and you’re trying to bring together these ideas. Can you talk a bit about the personal nature of both stories and this idea of “autofiction.” Way is that mode of filmmaking important to you?

CW: This phrase, “emotionally autobiographical,” has haunted me ever since I first used it. I used it as a cop-out to having to answer questions about autobiography. I read the synopsis about this pairing, but my film is entirely fiction. This film is very much based on me and my dad. That’s the core relationship, and the grief that I feel about his death is the core emotion expressed alongside portraying a very loving relationship. Looking back and wondering what was, I was thinking about whether things were as they seemed, and what I saw as a child and what I learned as an adult.

But there were different parts in which it was more fictional and less fictional. In the end, it sits somewhere in between. I was never on this holiday — I was on a holiday, shortly before my dad died, so it’s constantly negotiating that line. On some days, I am willing to acknowledge that line and the degrees to which it is very close. Other days, I have to keep it further at arm’s length.

Ultimately, you cast actors, find locations, bring in other collaborators, and it always becomes something else. Something that you fear might be recognizable to a person is normally transformed in making it, so that they don’t necessarily see. I have had family watch this film, and the details that they pick up on are, more often than not, totally coincidental. They identify clothing or props that I hadn’t chosen with that intent in mind. In terms of why, I think this film is coming from a place of quite sincere expression and finding a tool — cinema — to try and articulate a feeling that I wasn’t able to any other way.

Q: How did you make that leap from things that are true to your experience and then are fiction? For example, you went on a holiday but it wasn’t in Turkey, so at what point does that decision to set this fictional holiday in Turkey come in?

CW: I did go on a holiday in Turkey. I didn’t go on this holiday. These things didn’t happen as they happen in the film. In fact, some of the things that were specific to that holiday in Turkey aren’t in the final film. I went diving on that holiday in Turkey. I played [in] a pool tournament, which was in an earlier version of the film. They’re quite superficial details. Ultimately, what the film is about and the emotional progression of the film is very constructed for the film’s sake. The places where it’s absolute fiction are the most fun for me to write. When you’re writing and can see a scene — you look at it and think, “Wow, I didn’t have that experience, I don’t know anybody who did have that experience.” Yet the scene is now integral to film. I love finding the fiction within the world that begins from a place I know and that’s the foundation. Then you place the fiction on top. I’d be curious to hear how you [Mia] write in that sense: the relationship to discovering scenes from your own imagination versus being anchored in a sense of reality.

MHL: I could almost give the exact same answer as you did. I’ve been used to that word “autobiography” since I started making films because it’s always the word that defines how I write. In a way, it’s easier. I was told from my very first film, “Oh, this is autobiographical.” and I never actually said it. My first feature, for instance, was also a film about a father and daughter relationship, except it wasn’t me or my father. It was actually inspired by my uncle’s story. But because I said it’s inspired by somebody I knew, since [then] I was identified [as autobiographical].

In this case, my film is actually closer, much closer, to real autobiography. But what I mean here is that it’s never literally autobiography. Like you said, maybe the emotions are very close to mine. They come from my experience of life, and yes, my film was also inspired by my relationship to my father, who I also lost. But then a lot of other stuff comes in the process of writing, and at some point I reach that moment where I don’t even know. Strangely, it’s like almost vertigo for me, but I’m not sure anymore. I know about my feelings, about certain things like memories. It can start with memories, but at some point I get confused.

For instance, I did my second feature, “Father of My Children”, which was inspired by the last days of a film producer who I had known. After the film was made a couple of years later, I reached that moment where I wasn’t sure anymore what was the film [and] what I had actually been experiencing. Just like when you said you had not made that trip with your father in Turkey.

I made “Bergman Island” — which in some ways could also be called an autobiographical film — as a reinterpretation of my life, because I never made that trip to Fårö with the father of my child. It was just me, I was alone. So there is a lot here that was also invented, a lot that comes from my imagination. It’s the imagination and the experience meeting, and the fiction comes out of that meeting.

Q: What do the fictional aspects allow you to do?

MHL: It allows me to give a certain rhythm to the chaos of life. I think life is the emotions and experience that we make. For me, it’s a big thing. It’s difficult to find the right distance and to find a meaning to that, and by making it into a story, I try not to betray anything about what it’s really about. But I try to give it a frame — to look at it means finding a distance. It doesn’t mean betraying the truth, it just means trying to find the essence of the experience.

It’s actually a quest for truth and I try to reach it. But in order to reach it, I need the tools of cinema. I need to transform it into another language that gives a certain rhythm to it. That helps me. I understood much more about my relationship to my father after making that film than I did before.

CW: I think about moments that begin with memories. When you take a memory and you transform it into a scene in a film and then you shoot it, there’s a risk that you overwrite the memory, to some degree. You [take] this thing that’s very amorphous, and you make it real again. You put it in a setting, cast a person and try to recreate it. You spend months and months and months preparing to do that, and then shooting it and then editing it. It starts to really muddy what the source was. I’ve learned that before, and tried to be a bit smarter about that this time. I didn’t want to overwrite the memories that I have. Before I shot, I wrote a few diary entries of things I worried about that might happen. I want a record of what I actually remember of this experience before it becomes a scene in a film. It’s like with photographs when you’re younger. There are photographs I feel like I remember the moment, but I think I just remember seeing the photograph repeatedly from childhood. I don’t think I remember that picture of me in this rainbow ring by a pool when I was three, but I’ve seen the photo so often I have the impression of remembering that moment.

Q: You brought up the fear of overriding the memory. How does that play into the casting process with these films? You are casting people who reflect yourselves and your fathers. How much of what you know of yourselves and your fathers were you trying to retain? Charlotte, you have Paul Mescal. How much are you trying to bring something you know to the screen, and how much are you even, maybe, pushing against that in order to not have this direct conflation of memory and the film?

CW: I failed miserably at this. Because my intention is to cast as far away…

Q: Your dad was exactly like Paul Mescal.

CW: Paul Mescal was my father. My intention was always to cast away, because it helps create distance and create fiction out of something that began otherwise. As it happened in this case, I cast a kid who looks very much like I did at that age — as people like to point out, including my mother, who mistook her for me now. Which is confusing, because she’s 12. I think the same is somewhat true of Paul, I ended up casting very close.

I used photographs as references, [so the] costumes ended up being very close. I had sent my costume designer [Frank Gallacher] some family photos for style and things I had in mind. He came to the set with a replica of one of the t-shirts, and I was like, okay, that’s very close, I’m not sure I can have him wear that t-shirt. He does, though. I left the choice up to Paul.

MHL: Actually, to be honest, Pascal Greggory looks very much like my father. It’s different to me, the relationship I have with an actor who could be me or for the audience like an alter ego, the actor who is inspired by my father. I didn’t cast Léa Seydoux at all because she looked like me. She doesn’t, and I don’t think I ever tried to have her look more like me. Maybe she would say that she in some ways was inspired by me, because of course she knew how close her character was to me and she was probably influenced by just watching me. That happens a lot in films. When actors play in a film where they know they’re very much like the alter ego, they get inspiration from just watching [the person]. So maybe she did that, but I never intended to have her look like me. I was interested in how she would bring the character to somewhere else, and in that way, emancipate me from this experience.

But it’s different with my father, maybe because he’s gone and I miss him. I have a completely different relationship to the way I filmed Pascal. I asked him to play in the film not because he looks like my father [but] because he’s such a great actor and I wanted to work with him for a long time. But he does look like my father. It was just impossible to not think of it. Also, it deals with disease here and it’s a very particular, very special sickness. It’s not that I wanted him to be exactly like my father was when he was sick, but I just wanted it to be authentic. I wanted it to be true. So I tried to influence him to reach that music that I knew, how my father would speak, how he would behave, and how his body would move. Maybe it was partly because I wanted to get my father back. But I think it’s also because I wanted it to be as true as possible.

Q: Mia, you’re a big fan of Éric Rohmer, and Pascal is a figure in many of those films. In your films we’re encountering your memories, but maybe we’re also encountering your memories of cinema.

MHL: Yeah, although I never wanted to make films full of references [to] films that people would need to know. I never tried to imitate, for instance, the directors who I admire or put in references so that people would know that I admired these directors. But in the case of Pascal Greggory, yes, he’s been in some films of Rohmer that I love, and yes, Rohmer is one of my favorite directors. But I also think he represents speech or words, and that interested me because the character he plays in my film is someone who loses the ability to speak, to use words. That’s something that we can feel, whether or not we know these films that he’s associated with. I wanted people to feel who he had been before. Although I’m showing him at a moment where he can’t speak properly anymore, when he’s losing his memory and abilities of speaking in an articulate way, the fact that he was some kind of an intellectual — even for people who may not have known Rohmer’s films — is something he brings with him as an actor. I was interested in people feeling there is a world behind [him].

Q: Charlotte, this is your first feature. While making it, you’re drawing it partly [from] your life even if you’re fictionalizing it. Did films that you’d grown up loving also become memories that found their way into your film?

CW: That’s interesting. I have a different relationship to how films I watch find their way into my own work. Whereas I’m a little bit less shameless about taking things I love and employing them in some way, I don’t overthink that too much. I am very new to this, and do soak things up. If I read a book and then sit down to write, there’ll be a couple of sentences where the author’s voice is on the page. I see it and sometimes it amuses me and I leave it, and other times, I realize what I’m doing. I think the same goes visually. I’ve been working on this film for so long. The references that accumulated in watching for it and watching cinema did seep into the film.

Q: Are there any in particular?

CW: Let me give myself away. All the scenes people like to point out in “Somewhere” [Sofia Coppola, 2010], which I think is a more superficial reference more than anything else as a father/daughter story. He has a cast on his arm that’s coincidental. The underwater sequence from “Somewhere” though, was a strong point of reference.

The dance sequences from “Morvern Callar” [Lynne Ramsay, 2002] maybe were more of a straightforward visual reference. There’s a scene in “Alice in the Cities” [Wim Wenders, 1974] where they exercise together outside of a car, and that inspired the tai chi scene toward the end of the film. With the 360 degree shot — I saw “La Chambre” [“The Room”, 1972], Chantal Ackerman’s short, and employed the same thought at the end of the film. But that’s also because I’m learning as I go, and learning as I watch and am seeing. “Camera” is something I think about. I write in terms of camera. People keep telling me not to but I do anyway. So it’s just a way of it all bleeding in. I quite like taking references — not for other people to see, but because they inspire me.

Q: Both your films have given attention to objects. Mia, you regard objects as something that can hold much more than what is material, They bring forth ghosts; they sometimes blend the past and present. In this film there are many examples, but your father’s books are very prominent examples. Charlotte, that’s the case in your film as well, especially the sequence with the rug. It’s almost like the rug is getting to something that’s never articulated in the film — the scene where he is [merely] in the presence of the rug seems to articulate some kind of longing. Can you speak about the place of objects in your cinema?

MHL: It’s since I made my second feature, “Father of My Children.” that I started to be interested in how to film objects because the producer, who was the leader who was disappearing; once he’s gone there was this question about what actually remained of him and his soul. And the films that he produced, whether they say something about who he was, his presence, there’s a heritage there that we can feel — how it passes through objects. It’s not so much about the values of the objects themselves, but it’s more about them as a way of getting into the invisible. I discovered the cinematographic power of objects while I was doing that film. Since then, yes, I’ve always been interested in that and it’s even more true with this film, where Sandra’s father isn’t dead but his spirit is going away so she hangs on to this idea that his soul is staying through his books. I’m the same, actually. I used the books of my father in the film. I used the film, in a way, to get the books out of the boxes where they were in the basement of some friends, to get them back. I really enjoyed that, and think it’s part of what cinema is meant for. It made sense to me that making that film helped me in getting these books back. So yes, I really believe in this [idea of] “object” not as something that has an economic value, but more of an emotional value. I believe in them as an expression of the spiritual and the invisible.

CW: I’ve never thought explicitly about this before, but I’m thinking about it now. I think about objects in the same way I think about locations, in that these are things that endure beyond people — in a way that people don’t — and can remain unchanged. With this film specifically, there’s a lot of interaction with that in relation to location, but it’s the same thing you’re speaking to.There is the rug, but it feels like more of a tool to the story. I don’t remember the moment that I wrote the rug into the script. That’s an example of something that wasn’t specific to my dad. I grew up in a house that had this Turkish rug that I would pace up and down on [when] on the phone, and it found its way into the story. I think of objects in this film as locations and that they carry forward.

We had the camera — the camera is another [object], the physical camera that they had on the holiday which was brand new. By the end, she’s sitting there 20 years later and it’s not [new] and it holds the same tapes they had at that time and that her father held and put into the cassette. I think this is similar to what Mia was saying: they preserve something, they witness something, they hold all of this time around them somehow.

Q: Building off of that, can you talk about your respective approaches to time? Mia, with your films, particularly “One Fine Morning,” there’s this relentless linearity: time always moves forward [which] is somehow very affirming. It brings together the good and bad of life. They collide together on a single plane. Talk about your approach to time, and also how you work with your editor Marion Monnier, who you’ve worked with on all your films, to bring that approach into visual life?

MHL: It’s very defining for the films I do that I can never use flashbacks. It’s weird, because as an audience [member], I don’t have any problems [with it]. I love the use of flashbacks in films. I’m so obsessed with the passing of time that I don’t know how to tell stories in other ways, just chronologically. I can’t start a story with a scene that would be today and then go back in time. I just can’t. It’s not even like I think it’s good or bad. It’s just that I have to follow the time like it is. Not that I don’t think that the past can be within the present. It’s there, it’s how the present is haunted for me. I can’t do this thing that you do in the editing [where] you start in the present and go back in the past and then again in the present. The other thing that’s defining for my language in films is editing. Yes, we’ve been editing eight of my films together in a way that you feel life has started before and continues after. You don’t feel the beginning or the ending of the scene.

I’d like the audience to feel that life is like a train that started before and we just get on the train, and we go out, but the train didn’t start with the film. That desire of transmitting that feeling of life being constant progression and never stopping defines it.

Q: Charlotte, the good and bad and all the various experiences collide together in your film as well. It’s a young girl who is encountering a lot of news in life because she is on the cusp of adolescence, while clearly she’s anticipating a loss. Talk about how you approach time and how you worked with your editor, Blair [McClendon]?

CW: It’s interesting talking about flashbacks because the very first draft of this script, there was this rave sequence interspersed throughout. That was my very determined attempt not to have a secondary discrete timeline. I wanted to create this impression of somebody looking back, somebody working through memories of a specific point in time — without ever seeing the present day. Without there ever being a glance out a window and then a cut to the past. But in the script, there always existed this scene which I thought was insane. She was with her partner about three-quarters of the way through, and I tried to cut that scene so many times. I was like, that can’t possibly work. And people were like, no, no, I like that scene. It stayed in the film. Then as I progressed through the script, I added the scene at the end where she is there and it anchors a present-day timeline a little bit more.

For me, yeah, I’m interested in weaving timelines together. I love the work of Terence Davies [“Benediction”], and he talks about cutting, not for time, but for emotion and how that can traverse periods of time. That’s definitely something that interests me. Once we got to the edit, Blair found different strategies to deal with time that hadn’t necessarily been in the script. At first, those were constructed to solve problems that we had: problematic scenes, scenes in slightly awkward angles or light. But once the first [strategy] was constructed — which was the “Same Sky” sequence that uses her voice to bind together several different scenes — we start and end with her. We discovered that it lent something to the film and changed its relationship to time. That carried through to several other sequences in the film in a way that’s actually quite significant in terms of how the film is perceived by people.

There are three, maybe four, that really do create a different impression of time moving in and out of itself. In the script there was a more straightforward progression within the timeline of the holiday, of just moving from moment to moment and scene to scene. It always bothered me a little bit, because it was written as a memory, film as memory, and yet [there’s] this timeline that was very linear. It always felt a little bit at odds with itself. I also didn’t want the cuts to be arbitrary for the sake of fracturing time. So these sequences that Blair built addressed that, and contributed a huge amount to the film working.

Q: Mia, a lot of your films capture what it is like to love someone imperfectly or love someone that you don’t fully know or that you had lost before you can know them, but that love still persists. There’s a distance between the father and the daughter, but also the love persists beyond that. Charlotte, in your film it’s very stark that this girl knows that her father is in many ways a void to her. There’s a lot of parts of him that are opaque to her yet she’s asked, at a very young age, to love him in this complete way. Can you both talk about that, and bring that to the screen?

CW: That’s an interesting characterization of that. For me, that aspect of the film was about Sophia as a child not having that much awareness of Calum’s individual experience in that he’s protecting her from it. I think children perceive adults almost exclusively [in] the context of the roles they perform for them, whether that’s teacher or parent. I think love is fairly unconditional. There are moments of conflict between them, moments of frustration of expectations that are not, or cannot, be met. But the warmth and love between them is what the film is, and it ultimately transcends the grief that’s later experienced. In the context of the film, it carries forward to the implied future experience of Sophia as a parent.

MHL: Yes, I think love is very much at the heart of what my film is about, as in all my films. Love doesn’t necessarily mean happy love, that everyone is happy. The characters in my films have a lot of fragility. They are vulnerable; they are not perfect heroes at all, ever. That means there’s a lot of pain involved, but in the end, I think my films are always inspired by love. That’s why I would never make a film involving main characters that I would find horrible. I’m not saying it’s bad, but I think it really defines some films. I could never make a film with Nazis as main characters, for instance. I think life is too short for something like that. I don’t want to lose my time filming people I hate. That’s really defining for me. But what was special for me with that film regarding love is that I realized — and I realized it really late — while I was filming and not while I was writing. She loves her father and he loves her, but he’s not able to really love her because of his sickness. He’s not aware of his feelings for his daughter, and he’s only aware of being in love with the woman who’s with my father in the film, and she suffers from that.

There is love, but there’s also a lot of distance because of that. The one thing I realized very late in the process of making the film — maybe even while I was editing it — was the fact that he was in love with a woman and was obsessed with her. When his daughter comes to visit him he’s disappointed that it’s not her. At some point she becomes in love and that new love becomes very much the center of her life. That’s the one thing that unites them, that they have in common how much space they both give to love in their lives. So maybe it’s not the love he has for his daughter because he’s not capable of that anymore. But the fact that he gives so much importance to love and that he has this tenderness and need about him to give love, that’s actually something they both have in common. I find that idea very moving. I realized that instead of bringing more distance to them, it brings them closer together.

Q: That’s a feature of our relationship with our parents, where resemblances feel like love. When we start mirroring them, it feels like a gesture of love. Mia, your films are often talked about as women’s cinema. They’re characterized as part of this grouping or category maybe because people identify it as being about women’s concerns. What is your relationship with this term? For both of you, your filmmaking is about yourself. Do you have any relationship to the idea of women’s cinema beyond that?

MHL: I do believe that my films deal a lot with femininity and I’m not ashamed to say that. I don’t have any problems with people looking at my films this way, as being not only made by a woman but being very feminine. That’s fine with me. But I don’t think that only women can make feminine films. Femininity is something that can be shared by women and by men too. I don’t think it’s only a matter of gender, it’s a matter of sensibility. It’s one of the things that my films deal with, but hopefully, it’s also just one of them. None of us is defined only by our gender. I think you just write whatever you have to write, and I expect the same from the films that I see. I’m happy when I see a film and hear somebody’s voice. I’m happy if the person who makes the film tells me about himself or herself, and the more s/he does, the more personal s/he is, the more I can connect with him or her. So I’m trying to do the same because it’s the only way we can really say things that really matter.

CW: It’s an interesting question as it relates to the cause of biography and weighing in from a specifically personal place where you are. I was asked by a journalist why Sophie is in a relationship with a woman, and I was like, that is what I assume my characters will be. As a woman, that’s my experience, that’s what interests me, and I have something to say about. I think that’s also true making films as a woman featuring women, and sometimes making films as a woman featuring men. The ways I’m interacting with that question are through writing both genders. That was true in my last short film [“Blue Christmas”] in which the protagonist was male.

Q: Both feelings and memories are among the most personal things we have inside ourselves. Do you find it a bit frightening about the reception, how people will interpret something so personal, even if it’s not exactly as it happened? And if so, how do you deal with that?

CW: By sometimes pretending it’s entirely fiction [laughter]. One thing I thought about in making this film is that memories aren’t just yours. If you have an experience with another person, that memory is shared. You both have different experiences of it, but it is a shared memory. Then if one-half of that equation leaves your life through death or some other fashion, you’re suddenly alone with it, with half of the memory. This is something I thought a lot about when writing, and what it means and how lonely it can feel to be the only keeper of something that happened. I suppose there’s something nice about recording that and presenting it a different way and sharing it. It’s still true, it doesn’t change the fact of it. My film has brought a lot of people to share their own experiences with me and with each other, and that’s fascinating.

MHL: I do find it terrifying to tell stories that are so personal and looked at as autobiographical. But what gives me the determination or strength to still write them is that I don’t know how to do anything else. I don’t know what else to do. It’s the only thing I can find strength for; it’s a real necessity.

It’s an intimate necessity. I have this obsession about how short life is and how quickly time passes. I want to keep track of the presences who matter to me and I’m in this quest for meaning. So that helps me overcome the inhibition, and, sometimes, the feeling of shame — like I feel naked with my films. But I try to forget about it and focus on what I was trying to say, because there is no other way for me to make films.

Check out more of Nobuhiro’s articles.

Here’s the trailer of the film.

Aftersun

One Fine Morning