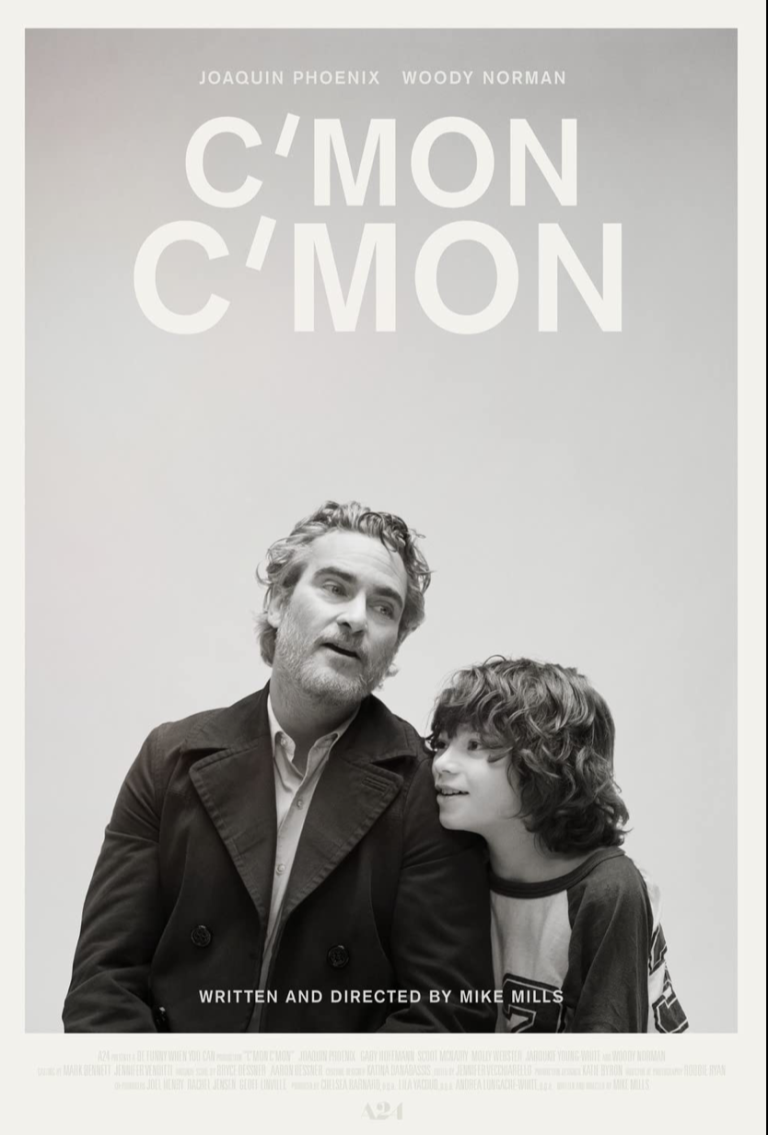

Synopsis : Johnny (Joaquin Phoenix) and his young nephew (Woody Norman) forge a tenuous but transformational relationship when they are unexpectedly thrown together in this delicate and deeply moving story about the connections between adults and children, the past and the future, from writer-director Mike Mills.

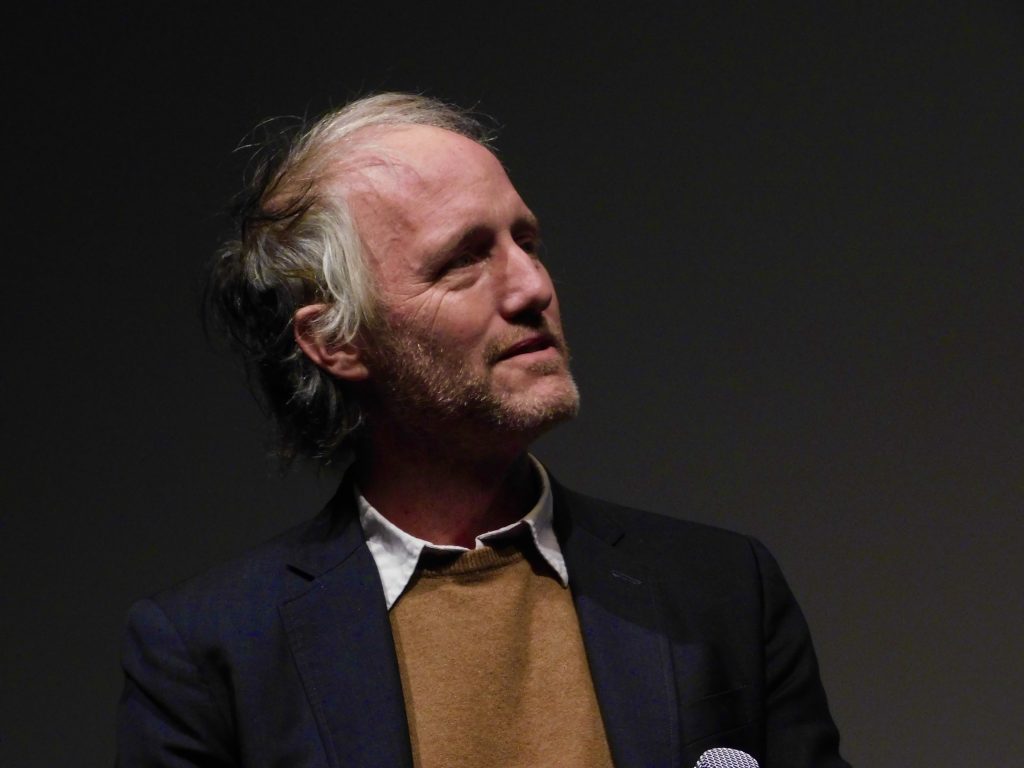

Q&A with Director Mike Mills on “C’mon, C’mon” (Q&A was conducted at the MOMA’s “Contender Series.”

Q: Thanks for being here. Thanks for this super-tender movie. Maybe we can just start with, there are these twin anchors that bring us through, the first being these really beautiful recordings with all these kids all over the country. Maybe you can tell us about how you found that as a way to anchor this story?

MM: First, it’s really lovely to see a room full of people that came to see my film. So thank you so much for being here. And thanks to MOMA for having this. Really, this means so much to me to show my movie in this building. I’m a museum director’s son, and this is sort of like Mecca, so it means a lot.

The story really starts with me and my kid, I have a child. It’s all about that crazy intimacy and vulnerability of walking through the world with the kid holding your hand. But I didn’t want to stop – I’m sure there’s tons of parents here, right? – so for me, at least, when I had my kid it really tied me to the world in a way I didn’t understand was coming. It made me feel so connected to other people and other kids — and all of us — in a way that I’d never experienced before.

So while I wanted to make this really intimate story, really a kind of small story, I had this other opposing desire to explore that as big as I could, and include all the kids I could – and to kind of de-center my kid. And that became increasingly important.

And then I just really loved the texture of the way, when you interview someone, the way they think and talk and reveal themselves, it’s so alive. It’s so carbonated, and so surprising – it has like an extra bouncy quality that really livens up all your written parts. It just changes the whole thing.

And then all those interviews, those are all kids who aren’t actors. Joaquin had a list that I wrote, but he would also follow his instincts with the kids, which was really beautiful to watch. He’s really such a sensitive, perceptive person that’s so aware of power and so good at dissembling it as you’re in the room with someone.

Often Joaquin walks in the room and there’s a kid, like, “You’re the Joker!” I was really worried how that would go because – it was Fall 2019, right? so Joker shit is everywhere. Joaquin would so nicely go “Oh, totally. Yeah, let’s talk about that right after. Um, what are your shoes?” And when Joaquin says “What are your shoes?” it has a certain power to it – not because it’s Joaquin, but because he knows how to have energy and you just start answering. So that whole process was really quite beautiful. It influenced the whole filmmaking process

Q: Maybe you can tell us how you guys moved around the whole country, right? New York and L.A., were really intrinsic to the story, but then you have these two other poles [New Orleans and Detroit] anchoring us.

MM: That’s a good word, “poles”, and it kind of ended up making some sort of a cross in a funny way. We did it in order. I shoot most of my films in order because all the stuff accrues and happens that you never could predict to the crew and to the actors. I try really invite stuff that I didn’t see coming, like I hope for and invite. I’m looking for it and I want it so it comes. So it’s great to shoot in order because then you can adjust or you can discover something and then incorporate it in a way that makes sense.

So we started in Los Angeles, went to New York December of 2019, and then went to New Orleans. We shot Detroit at the very end. It was because it was only a few days there, really. Relationships with everyone grows, but especially between Joaquin and Woody, who plays the kid. By the time they’re in New Orleans, I’m just wildly jealous of their relationship.

They lean on each other, they have their own weird language I do not understand, take pock each other’s noses, literally. So the human in me is like “I want to be in there”. The director in me is like “this is gold! This is what you need, this is what you want.” And this is what it’s my job to encourage and enable and make happen.

Q: So the moving around in some ways creates this kind of road movie. Did you think about it through that lens?

MM: Well, I thought about – it’s like an airplane movie more than a road movie. The road movies are such a thing. I really did think of it as a cities movie and “Alice in the Cities” was a very big influence. I couldn’t have made this movie without watching “Alice in the Cities” as a way to recover from 2016. So I just watch it all the time as kind of like Zanax.

Because I was lost, really lost, as to what to do. I wanted to do something about my kid. I didn’t know how to do it. I was like, maybe I can use this as like a blues structure, a blues chord thing, and I’m going to put my own lyrics and my own thing in. So I do owe Wim Wenders a lot for that.

Yeah, I wanted it to be scenes about giving a kid a bath as the core. But then I also want to thrust that mystery of that relationship out into America at large, and especially after 2016 I really wanted to somehow – not that I have any great resolution or understanding or anything. I just want to be in it – kind of in the mess.

Q: I feel we shouldn’t go any further without talking about Woody – such a revelation, especially alongside somebody like Gaby and Joaquin. They really feel like such a real family. It’s hard to believe that Joaquin and Gaby never played siblings. Can you talk about them building a unit?

MM: Do you know that Woody’s British? He cruises in doing that accent, and I can’t do a British accent. When I said “Cut” he said “Really?” It gets you every time. So let’s park Woody for a second.

Gaby and Joaquin, two people I’ve always wanted to work with, that I really admire deeply, I’m so taken by their work, in different ways. Didn’t know either of them, felt so wildly lucky to get them. Getting Joaquin was one of the more tricky, difficult things in my life — to get through that jungle journey with him — to get him to say yes.

They both weirdly had this idea, like “We should not meet. We should never meet until he walks through the door in Los Angeles.” And I, who love Fellini, was like, Well, the film gods are telling me this is what has to happen. Because I like a lot of prep, I was like “Oh, let’s do all this experiential, improvisational Mike Lee process stuff.” They wanted that, so I was like “Cool. Let’s do that.”

So that was the first time they all met, and it was really effective in the way they did it. It was not as I expected. I think the scene is great, it’s fine. It would have been the same, I think, if we had prepped or done something else.

They’re all so good. There wasn’t a problem. But what it did [was] it scared them so much – the actors. And those are two actors who are the kind that are easily bored. So it hot-seared them into their gestalt with each other, and they kindof like cried after Take 2, because it was so much nervous crazy energy.

What Gaby said to me that I thought was really profound and I just trusted immediately was, she said “I know him” – she had never met him. “I know him. He is my brother. I feel like a familial situation. I can’t explain it to you. I do. So therefore, it’s there. We just need to kindof crack it, and it will all kindof spill out.” I like that, even just a physical gesture. I was like, “I get it.”

So there wasn’t my usual long prep situation. The same thing with Woody: we did some things together. Gaby and Woody did hang out. Joaquin and Molly Webster from Radiolab who plays the Roxanne character, they did radio stuff together, but that was when they happened.

And then for the rest of the shoot, it was in a very sibling situation: they’re either making each other laugh so much I couldn’t film, or they were arguing so much I couldn’t film. If Woody was here, he would do this big performance for you, like “They were so impossible.” And it’s true: they were the children on the set and Woody was the grownup. All felt very familial – familiar and familial – and that’s so how it is in my “house”.

Q: You achieve a naturalism that I think a lot of people strive for but few really succeed. It’s really in just the smallest gestures. How did you achieve that, staying close to the text you’ve written?

MM: A lot of that is obviously just letting things happen. I shoot in series, so I don’t say “Action”. We just start, they all know when the camera’s going and they’ll do a take, maybe we’ll have “still rolling”, and the cameras are all going, maybe say a couple things.

To do it again, maybe all go plop down on the bed that we’re shooting on and chat for like a second, camera is still rolling. So you’re on kind of this constant simmer, but not like the thing of “[Ohh!] We’re gonna do a take” and then we’re done. We’re simmering for fifteen or twenty minutes, and I find that really helps for that quality.

Another thing I think people don’t realize: it’s so much about the editing. Being brave enough to include the little moment where they’re lost and just playing with the napkin, or all the little things that are behavior- and not dialogue-driven; looking for those moments, and then believing all that story, actually, and that kind of pushed the boat forward.

Another thing is, your film sucks until it’s okay. Like in the edit, it sucks, it’s so bad, until the last minute. No one told me this for years. All those moments I just described – just coming through a door and being nervous and hanging out — you’ve got to cut that out, and get to the moment when they’re talking and the thing happens – “the thing”.

It took me a long time to understand this will slowly figure itself out, it takes a long time to build the brain to be able to finish your own film. The filmmaker doesn’t have it at the beginning. So it’s a lot of editing, it’s such a huge part of what a performance feels like on screen.

Q: Another framework is something that has been in your last two films as well, which were these texts. In “Beginners” we have The Velveteen Rabbit. In “20th Century Women” we have [writer] Judy Blume and all these things that bring us into the larger culture. How did you find these three or four texts that guide us through this film?

MM: In this film? From the ones you mentioned, like The Velveteen Rabbit [Margery Williams, 1922], that’s real. My dad had a show about teddy bears, and put the Velveteen Rabbit quote on the wall a week after Harvey Milk was assassinated. That came from personal discovery.

I really love observing the world and being a good observer. That’s my favorite thing, and to find ways to incorporate it. And then that’s when the writing happens. It’s like, all these things I love. How do I put them into something that means something?

So those texts — I read Star Child [Claire A. Nivola] to my kid all the time and they make fun of me for crying, and they like [smack forehead] “Mike, don’t cry again.” So that whole scene is really from my world.

And then that Jacqueline Rosa is so piercingly accurate, I found, as a father-man-person. But from what I have observed from the moms around me, I felt that was so wildly accurate in such a condensed, sharp way.

So there are things that I have collected. The Kirsten Johnson piece is amazing. That came in the edit. I actually did a Q&A with her while I was editing my film. It reminded me of her amazing cameraperson essay and how personal and direct in admitting her own complicitness in different parts of the documentary process.

There often are things that I just love, and I’m like “Well, if this is in my movie, maybe there’s half a chance it’s okay”. And it’s like “Company,” in that way. If you have a great thing on your team, maybe you’ll play as good as the other members of the team.

Q: I can really understand your last few films existing in the same universe. Do you think about this one, particularly in dialogue, with the other two films?

MM: I didn’t see this coming. My dad passed away in a very kindof dramatic way and grief can give you so much bravery. It’s kind of hallucinogenic. I was braver, smarter, wilder than I would have been if my dad was all those things. I blame my dad, you know?

My dad came out when he was seventy-five and really went for it. And included me in that trip. He was a very staid person before that, so he was quiet and experienced. And I feel like I’m still – like he pushed the canoe and I am still on the canoe from that experience.

So he came out. He was born in 1925, and he also had so much embedded self-hatred, embedded self-shame, and all that. He came up out of all that and he became politically active right away – or socially active about his gayness right away.

That whole connection between that which is wildly internal and personal and that which binds us all together in a socio-political way, became really accessible to me. So I feel I had been finding that spectrum. And the same thing with my mom, her time on earth and how it relates to being – feminism, in a way.

So that first film really taught me that I could write from a really personal place and it can connect with strangers in a dark room. It can connect. That’s an amazing, miraculous, magical situation. So yeah, that did point me in this direction. But I’m kindof surprised. I’m surprised, and I’m totally not surprised that I’ve done these three [films].

Q: It’s funny to hear you say that because I wanted to ask you about spirituality in your films, which maybe isn’t something one would think of while watching your films. But they make me feel like a larger force – and maybe that kind of grief is actually the thing behind it.

MM: Yeah, big time. Do you guys ever read Fellini interviews? Just go home and get it. Read it.

To me it’s like Pema Chödrön. You ever read Pema Chödrön? It’s deeply spiritual. There is so much energy that goes into a film; so many people, so many decisions, it’s wild. It’s like Las Vegas on drugs. She talks about them as these sortof psychic soul entities that you summon, you ask for, and they come. And they come with their own needs and they summon different people.

That sounds very spiritual, right? I fully believe that. That’s my experience. Films have personalities, they have ways that everyone on set feels, and they have ways that audiences feel. It’s really trippy, so I’ll be doing press, and I’ll do it here, and I’ll go to different countries. There’s like four or five questions each film will summon, or four or five moods or feelings. So I do really believe in that.

I think you’re right to base it all in grief, and some sort of connection with history. And I find history to be kindof a spiritual situation — our relationship with it and how it affects us. And I think filmmaking in general — okay, the older I get, the more I find it to be a bonkers, pagan, spiritual deal.

Q: Yeah, that sense of history and humanity is something I feel so much in this one. You see Johnny tired at the end of the day, immediately reflecting, taking this thing that happened in the moment and capturing it in his own words, and kindof making this artifact to pass down this intergenerational [moment]. Can you talk about those moments with Joaquin, having him narrate the scenes?

MM: That was really interesting to get Joaquin to be this radio person — to get Joaquin to do something that was kindof naturalistic. He’s so suspicious of “naturalistic” editing – you always say it with quotes — because he’s like, “what is more contrived than acting normal? Or like walking through a door and saying “hi” but with a film crew? That is such bullshit.” So it took a long time to find a way for him to feel comfortable or have entry.

Studs Terkel really helped. I love “This American Life” and Ira Glass and ________. I told him. And he was like “yeh”. But Studs Terkel and Ira Glass told me about Scott Currier, who I had heard before but didn’t really have the name. Studs created this amazing journalist who works mostly in radio, and does podcasts now, but has a really specific voice. It’s often very monotone and kindof flat, and often talking about very dramatic things in that way. But has a real gift for “the small” and how “the small” is big.

Joaquin is like, “That guy is it!” So right before we started shooting, maybe a week before, he’s like, “Maybe I do kindof Scott Currier-like, just processing my days.” I said “Yeah, great. Sounds great.”

When an actor starts to author stuff, to me, that’s always like, yes, you got under their skin. As a writer-director person, that’s the best sign. I’m always going to invite that. And who knows how it’s going to go. And Joaquin, first of all, would be [hah] Who knows? It could be the most indulgent, ridiculous thing. He might even say it is now, if he was here.

So we just started doing those about every three or four days. I would start by writing what he’s saying. But he would just start to remember. Because we were shooting in order, he would just live through those scenes a day or two before. So he’s mostly really remembering and it’s really beautiful. He’s struggling to remember and catch it down. I don’t know why I find that very emotional, and very human or something.

And to me, that’s what films are, right? It’s trying to hold on to our confusing lives that we don’t understand, and maybe we can – I don’t think we can understand it better. But we can hold on to the fact that we don’t understand it a little better, and it doesn’t slip away quite so fast. That’s an Oscar right there, if you can do that. So the film kindof started doing that inside of itself a little bit.

Q: You make these really comfortable domestic spaces in this film – and all of your movies. When I think of your films, I think of dried flowers, like a flower on a window sill or something.

MM: Do they have to be dry?

Q: They often are – I don’t know if you’ve noticed.

MM: Like a few days old, still in water, and it’s okay, right?

Q: But I guess not even from a production design standpoint, but maybe just textually, like how you go about building those, in service of a character’s story.

MM: That’s really interesting. Well, a lot is “as is”. So Viv’s house in Los Angeles, that’s my friend Maximel’s house. That’s — ninety percent is their stuff, and all the layers, and all the clunk and all the taste, I guess, too, like layers of aesthetic decisions over the years. I find that really hard to recreate.

Johnny’s apartment in New York City: that is created. That was a barebones space. I had an amazing model of how to make that apartment look, that we definitely studied and thought about a lot.

I love place. I feel like either an interior like you’re describing – or even an exterior – I like to leave it alone and use natural light. Natural light is really huge — natural light, not lighting things too much. Usually if I’m sitting here in mind of a film — like right now, there is a spotlight on me. So you light for the face. Anyone like Gordon Willis and those different heroes of mine in cinematography – you light for the room, not for the face. Or better yet, you just don’t light. Because it bathes everything in this kindof dried flower vibes, maybe.

Anyway, I felt like place – and to bring up Wim Wenders again, I think he’s so good at place. When you watch one of his movies, it’s like, well, those emotions, that scene, that dialogue, that need, could have only happened right then, in that situation, next to that wall, a light coming there, and that piece of trash over there. It’s all a “thing”, right? So I definitely think of place and dialogue as together

Q: Maybe you could tell us a little about the cinematography process. In the black and white, there’s so much gray range, it’s not so intensely what you might think.

MM: Yes. Robbie Ryan is an amazing cinematographer. He does Ken Loach, Andrew Arnold, all those natural light [films] and that’s part of why I reached out to him. He’s Irish, charming, and lives on a boat in London – can’t be more charming. Travels everywhere with one bag this big – that’s it.

Robbie doesn’t like a lot of stuff. Robbie loves to turn the camera on, so he’s like my favorite date. It’s like that’s all we need to be best friends. We use a tiny – not like a dolly, just like a post on a skateboard platform, with two V-channels that are, like, totally illegitimate. But it takes one person to set up, and it’s so light on the land and it kindof creates a vibe on the set. I go “That’s your dolly? I don’t even know if this is a film set.”

Often we’re shooting in New York City streets. No one knows we’re there. Those shots on Grant Street, before he goes into the pharmacy with all the people. So we just put up the sign on either side of the block and that’s just everyone walking home. And Joaquin’s really good at being not the droid you’re looking for, and just going out into a crowd and walking towards camera, and no one knows that we’re filming a film.

Same thing when they walk on a beach in Santa Monica, he’s on the phone. All those people do not know they’re in a movie. It might not be even legal, I’m not sure. But we put the signs up, and the poor woman in the bathing suit, I was going “Is this right? I don’t know.”

At one point, there was one take where Joaquin’s going and talking. We’re doing the scene, we’re down the beach on a 150-millimeter lens. I’m like, here, and Joaquin’s like towards the end of this audience.

He’s walking, and there’s an iPhone in the sand. He’s doing the scene, he’s on the phone – he’s really on the phone, with Molly Webster in New York City. He picks up the phone, and he [hands it to someone] and says “Hi, is this yours?” He’s still talking on the phone, and “Yeah, he’s amazing, he’s doing great stuff. You should see him.” [While handing the iPhone to someone]. “Yeah, I think you left it.” She’s like, “No, it’s not my phone.” Joaquin [looks at the iPhone] “Well, will you take it?”

It’s all on film, and so that kind of vibe was existing all the way through. I completely lost myself in that story.

Q: Cinematography?

MM: Right. The graininess that you were talking about is interesting to me. I love Satie, piano. I love the way you can enter the music, literally, like the notes are so far apart you can walk in between them and get in there and look around. I find that space and that openness to be super-beautiful and healing. I would love to make a film like that.

To me, black and white is like Satie piano. It doesn’t talk loudly at you, it talks like this, and you have to kind of lean towards it, I find. I thought that that would be really a beautiful way to capture what it’s like to give a kid a bath. And to invite everyone in with you doing that, or be in bed with the kid. That sort of quiet whispering intimacy is part of the film.

The grayness you’re talking about is because we used mostly natural light or just a little bit of practicals in a room, and so it’s low-lit and has some non-pointing quality. It makes me feel just comfortable.

Q: Before we go, I just want to ask you when you think about the future, what do you think it will be like?

MM: Every once in awhile a kid will pull that on us. Like at the beginning, we said “If there’s any question you don’t feel comfortable with, you don’t have to ask, you say “skip”. Molly taught Joaquin to do that. They’d often say “If there’s any questions they don’t ask that you want, just ask.”

So everyone once in awhile I would see a kid ask Joaquin and Joaquin would go – and Joaquin’s a very pessimistic – big, big, huge-hearted, sensitive pessimistic person. And there’s a ten-year-old asking that question. And I watched Joaquin just want to cry.

That’s sortof my answer. It’s so heavy to me right now. So I guess I don’t feel it’s a hard question.

Q: That’s okay. Thank you so much.

MM: Thank you.