Leon Vitali, born in 1948, English actor Leon Vitali’s collaborations with Kubrick both as his personal assistant, and as an actor, most notably as Lord Bullingdon in Barry Lyndon established him in a way few can claim.

In 1974 Vitali met Kubrick, with whom he had a professional relationship for the rest of Kubrick’s career. While played Lord Bullingdon — the title character’s stepson — Kubrick and Vitali bonded during the shoot. As filming concluded, Vitali asked Kubrick if he could stay on, without pay, to observe the editing process, to which Kubrick agreed.

Five years later, Kubrick sent Vitali a copy of Stephen King’s The Shining and asked him to join the production of his next film. Vitali is credited in The Shining (1980) as “personal assistant to director.”

Vitali teamed up with Kubrick again for 1987’s Full Metal Jacket, where he served both as casting director and assistant to the director. Twelve years later, Vitali was credited with the same titles in Kubrick’s last film, Eyes Wide Shut (1999), in which Vitali also played Red Cloak. In the film, the words “fashion designer Leon Vitali” appear in a newspaper article that Tom Cruise’s character reads.

Since Kubrick’s death Vitali has overseen the restoration of both picture and sound elements for most of Kubrick’s films. In 2004, Vitali was honored with the Cinema Audio Society’s President’s Award for this work.

In 2017, Vitali was the subject of Filmworker, a documentary directed by Tony Zierra and produced by Elizabeth Yoffe which premiered at The Cannes Film Festival and screened at many U.S. and international film festivals including 2017’s London Film Festival. In Filmworker, Vitali is interviewed at length about his work with Kubrick.

An Exclusive interview with Leon Vitali, he recalls his many odysseys with Stanley Kubrick and how it changed his life.

Q: Why did you decide to quit acting and end up working with Stanley? You had quite a career before that. You were discovered through working on Barry Lyndon. You had this whole other career — leaving that was quite a tremendous move.

LV: What I always felt was, if I was doing a piece of theater that was fine, because you are there from the beginning to the end — not just [as part] of the process, but with each performance, whether the part is big or small. But for the most part, film is really about… Well, you get called on the day you’re going to shoot and you do your thing and that’s it. You have no further input, and you don’t know what’s going to become of it. You may end up on the cutting room floor, for all you know.

But the thing about watching all this work going on around you, you’re realizing how many people it was taking to actually put something together, and that you were there from beginning to end of the process. That for me was much more stimulating, really. That is not simple, it’s very complicated because simplicity is the hardest point to get to.

That’s what I always felt. To keep something simple is very difficult because things can get very complicated very easily. So it was all that that made me think, well, this is where I really feel like I could be at home. Just immersed and surrounded by doing the thing you love.

I loved acting, it was great, wonderful work. It’s not like I stopped completely. I’ve done other bits and pieces. But I have fun with it where, if it had been my life, it would have been more of an ambition-driven thing. But this is apart from now, working quietly behind the scenes, putting things together.

This is the other thing: you meet wonderful people. You meet some assholes, too. But you do meet wonderful people who don’t just go the extra mile, they’ll go the extra hundred miles. They understand the vision and what’s at stake. You meet people you would never have met before, and you see each other at their weakest and strongest. That’s a beautiful thing.

Q: When you worked for Stanley, did he ever tell you about a Napoleon project? Whatever happened to that? Did you two ever talk about a future project like that? (Back then, Steven Spielberg was tackling the Napoleon project)

LV: The thing about Stanley was — A Clockwork Orange, with all the fuss(In March 1972, during the trial of a 14-year-old male accused of the manslaughter of a classmate, the prosecutor referred to A Clockworks Orange, suggesting that the film had a macabre relevance to the case) was about, especially in the UK, he withdrew it. It was something he decided to do. People were always going on about, “Oh, he should re-release it, rerelease it, rerelease it.” I used to say to him, “People just want to see this film.” And he said, “It’s not a question of never, it’s a question of when.”

You could imagine that Napoleon project is always sitting there, it was just a question of when. I honestly think he would have embraced the idea of 10 one-hour episodes because the story is so huge. But the thing is, the technologies available now, he would so have embraced.

It is amazing what television has now become. It’s taking the place of feature films. The budgets are getting huge. They are tackling things they probably wouldn’t have done 20 or 30 years ago. It’s opening up in such a way — with Netflix [et al.] — he would have loved it.

I know he would have loved digital cinema. People would come to him and say, “Well, are you happy with this camera?” Arriflex’s people used to come and say, “Take a look at our new camera.”

We’d be standing there and he’d look at it, looking [through it], handling it, every little detail. And he’d be quite candid with them. He’d say, “Well, that’s almost there, but it’s still too cumbersome” or this or that. They would go away and work to improve it. That’s very much how he would have behaved with digital cinema. He would have made demands. I don’t mean “do this, do that.” He would have said, “The problem with this is you can’t do this or do that”, and it would have encouraged people to solve those particular problems.

Q: At one time, he was working on the Holocaust in the 1990s, before Schindler’s List came out. He had to cancel the whole project. How much was he working on it back then? Was he writing a screenplay?

LV: Oh yes, there was a screenplay which wouldn’t have meant much after he started shooting. He would have changed it.

Q: Was it based on The Aryan Papers?

LV: No, Aryan Papers was the title Warners wanted for it. Stanley came across a book called Wartime Lies, and the point of the book is that it’s a child’s story about what he remembers — an adult’s story about what he remembers as a child during that period. That’s where the word “lies” comes in, because is what he’s telling accurate? Or is it embroidered? Is it true? What is he exaggerating, or what is he not saying? [Kubrick] was interested in the psychology of that situation rather than “This is the Holocaust”. He wanted a part of that thing where he could study it and examine it.

I loved the idea of making a film about someone’s remembering something and is it accurate, is it true, is it this thing or that. But the thing about when Spielberg’s film came out, it was so stunningly successful — and we were actually in Europe and had a whole list. I had started looking for actors, and got a whole list of armaments and vehicles and everything. We went very deep into pre-production. But the thing was that when a film comes out like that and it’s so successful, that’s The Holocaust film.

It was the same after 9/11. There were a lot of people that wanted to make films about the Middle East and what-have-you. I had a project with Todd Field (who made Little Children). And everywhere we took it, people would say, “Oh, there’s already an Arab film out there.”

The first thing we had to say was, “No, it’s not about Arabs. They’re Aryan, they’re not Arabs. Because Iran means ‘Aryan’ in case you didn’t know.” And also, they felt like, “Well, once you have that story about Arabs in a state of war (or whatever it is), that’s it. You don’t need another film.” It’s so blinkered.

Every story has its cycle inside the Hollywood psyche. It may not be the time to tell it. And I think you see, from all the films made about Iraq and what-have-you, none of them were particularly successful — although there were one or two that were. Probably because it was too soon. They needed some more years and more objectivity.

Q: Critics often say Kubrick’s movies are detached from emotion or have a cold or bleak perspective. But when I saw Barry Lyndon, especially the sequence when Lyndon meets Lady Lyndon for the first time with Schubert’s music… They’re working up to a kiss without saying a word. That’s one of the film’s most beautiful sequences; it’s so emotional. Weren’t you frustrated that some people say he had a bleak or cold perspective? He reveals so much emotion in the film.

LV: I absolutely agree, and yeah, it was very frustrating. He [was] an observer, first of all. There’s a wonderful line in Hamlet where they talk about Hamlet saying “He’s the most observed of all observers.” And I think that was the thing about Stanley: he was an observer of people who were looking [going] “What are you observing?” So for any film that he made, there were a whole bunch of movies that were very influenced by it.

The thing was, he was an observer, and the real thing is there were those films [such as] Barry Lyndon, where if you didn’t get the emotion coming from that, where are you? He was showing you that emotion exists, and warmth exists — but so, too, does the other side of the equation. Life is not “they fall happily in love forever after.” It’s about challenges and temptations, everything that every human faces in life. Life is a tricky thing for a lot of people to live through.

Q: In Barry Lyndon, you played Lord Bullingdon. But I hear that Kubrick’s always preparing more actor, in case it doesn’t work out.

LV: What often happened with actors… They’d do the audition and because it was with Kubrick, they’d get worked up about it. They’d come to the set, and often it’s very difficult. You have to shake off this idea of “I’m acting for Stanley Kubrick.” No, you’re acting for the film. I didn’t work with the Toms and Jacks and Ryans, but I worked with just about everyone else in the industry.

When I worked with the actors, the target was just to get them to forget it was a Stanley Kubrick film, and get them to understand that it’s not a question of remembering your dialogue, it’s a question of knowing it so well it’s stuck in the back of your brain, like a muscle. You don’t have to think about it. For one reason or another, it would often happen that — especially for small roles — they’re very, very difficult sometimes. And they’re too tense, or trying too hard.

It was just ironic that we had to shoot three George III’s. It was the third one. Actually, he was good. He came in and was able to do it and understood [the character]. That’s a common problem for every director, to get them to drop their personalities or identity so they can not think about being a tough guy or not think about, “this is just their nature.”

That’s why Stanley loved stuffed animals: because they don’t have any guile, they are what they are, they are what they show you. Humans are like that, too, but we cover it up with guile, trying to work our way around a situation or to get through a situation. What he wanted was somebody who was in the middle of a situation and they were just responding the only way they knew how to do it. I always tied these things together with Stanley, the way he felt about stuffed animals and what he was trying to get on the screen.

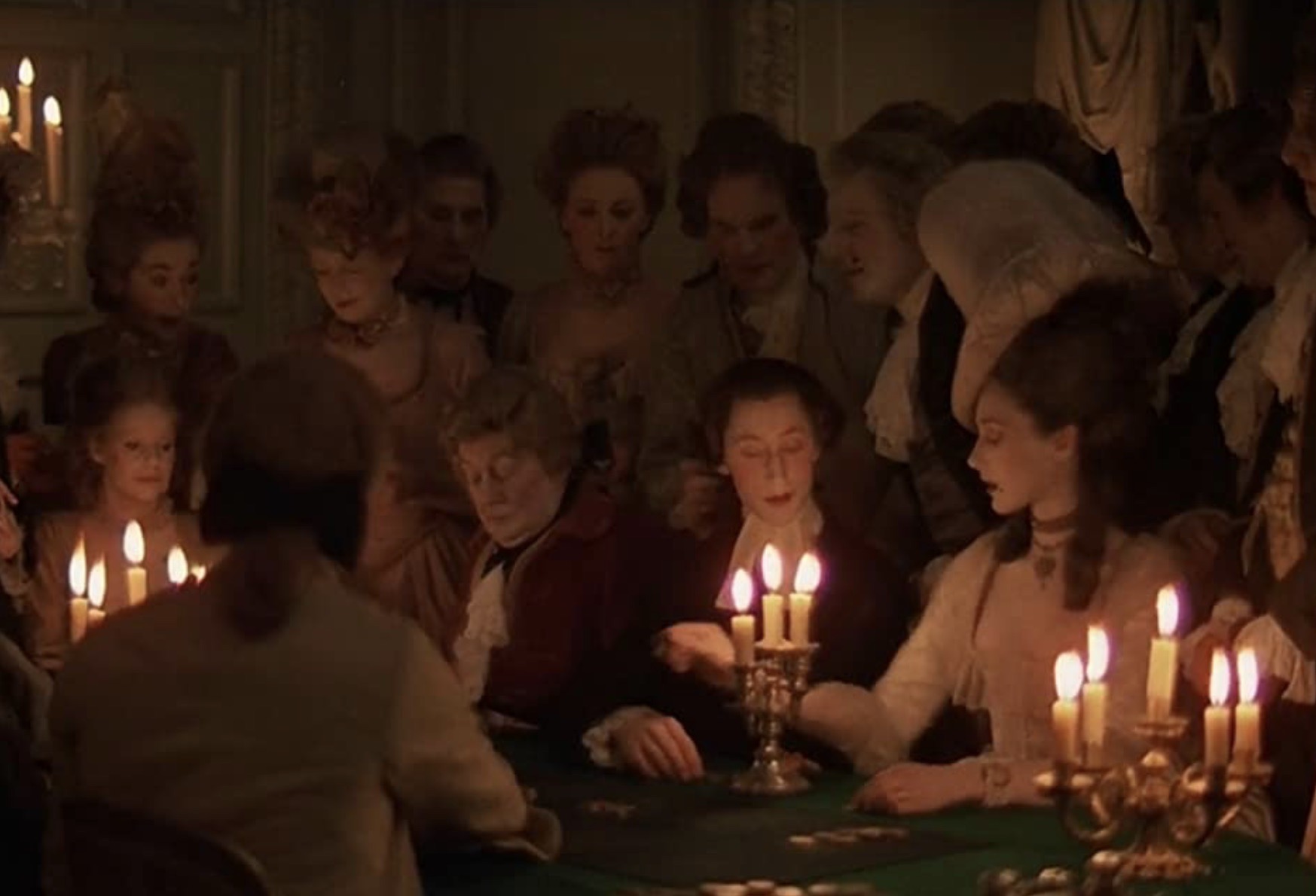

Q: In order to capture the candlelight in Barry Lyndon, director Stanley Kubrick used a NASA lens(The Carl Zeiss Planar 50mm f /0.7). It’s quite difficult to capture that light; how did he do that?

LV: It’s a question of exposure and what he discovered was, with single wick candles, you just couldn’t get anywhere near what you needed to get. He got them working on a lens that was actually designed to go to the moon. 0.7 was the widest aperture that you could probably find anywhere. So he started that, and then he discovered that you can make triple-wick candles. That helped with giving him a little more exposure. Zero point seven really just about made it. He did not get any depth of field, that was the only drawback about it.

Q: With most of the sequences, shooting by zooming was so hard to tackle.

LV: Yes, it was. I didn’t know very much about any of that kind of stuff before. But suddenly I was getting so interested, and just swept up with it. You realize how many people it takes, and how difficult it is to keep everyone on track. It really is. It’s not an easy thing, because some days are bad days because nothing is quite clicking together, and it’s very frustrating. It can be. But at the same time, there’s a sense of triumph when you found a way to make something work. That’s a beautiful feeling that I had. I still have, really. It’s a great feeling.

Q: Were you surprised when Stanley called you to cast Danny for The Shining, and take pictures of all those hotels? Even though he requested it, he said you had to do something about it and gave you the outlook, but you still don’t know what’s going to happen. You had to work out that film to get to that point — were you surprised?

LV: Stanley was very good at remembering things people do and how they could fit in. This thing about, he had another casting operations in L.A. But what he wanted was because he knew I could improvise. When you’re handling young children, that’s the best way: play around on the floor, get on your hands and knees, pretend to be animals.

You slowly get them up and get them to focus. I had them talk straight into the camera to see how long you could keep their focus or their attention. When you give a young child something to do and you want them to do, it’s very rare that they stay that focused for more than 10 minutes.

Danny could stay focused, and he was only four years old. That was a remarkable thing. He was four years old when I auditioned him.

[Same with the twin girls.] Just think, if I hadn’t been so into Diane Arbus, that would never have occurred to me. But as soon as they walked through that door, it was like, “This is it. You don’t have to look any further.”

With Danny, out of 4000 boys, it was obvious at the end of it that he was the only one it would work with. It’s astonishing, really, the little nuances and differences in personalities can make, especially with children. They all have the same fears and so on, and at the same time, what they think about makes the difference.

Q: That approach might be difficult with someone like R. Lee Ermey in Full Metal Jacket who was working as a technical advisor for a several months. All of a sudden, he has to go make it because of an incredible actor who can basically seize the role.

LV: The thing about R. Lee Ermey, who created that role, he had done two, three terms in training at Pendleton and Parris Island and also had done three terms in Vietnam. When we were auditioning for the extras — the platoon and the rest of it — to bring them in, we started off with their sitting down, saying their names, “what do you do,” “in the army, what’s your area,” “what was your responsibility?” And I thought, that doesn’t show us anything. Yet there’s no script, you can’t ask people who have never acted — “just do an improvisation and let’s see if you’re any good.”

Lee Ermey used to turn up because he was our technical director. He always turned up immaculate: pressed uniform, medals, everything. Everything. I suddenly thought, well, he told me stories about kids getting off the bus and being lined up and getting a big shock. So I said, “Why don’t we do that? Just line up all the kids and you do whatever you used to do at Parris Island and we’ll film it. That way, we’ll see what these kids are like and how they can stand up to it or not.”

When I showed Stanley, he just couldn’t believe it because the DI [drill instructor] was so outrageous. [Stanley] had to laugh at just about everything he was saying. And so that interest in that angle instead of just being the usual idea of Marines — this guy was it.

I kept video filming all the auditions we did. Then, we wrote down all the dialogue; we transcribed it. Stanley and I and Lee Ermey went through it line by line. “Oh, let’s take that line, that’s a great line.” “No, not that one, not that one.” “But this one is really good.”

We cherry-picked through 800 pages. Absolutely. It was amazing. And often it was repetitive, of course. But very often, they were just beautiful nuggets of gold that only a drill instructor would know. And you know, it’s a matter of life and death. That’s what those DIs — you don’t have to like them. They’re telling you “This is how you survive.” If you’re lucky enough to survive. So there’s a hard edge there, too, which is important.

Q: You weren’t there for the making of Spartacus, but I know Kubrick hated that movie because he didn’t get the director’s cut, right?

LV: He didn’t want it.

Q: Kirk Douglas hired him, but he didn’t support him.

LV: It was frustrating for Stanley, of course. And when that project when Stanley came to it because they had to remember who the director was — he shot for about a week, two weeks, and they got rid of him. Then Kirk had remembered Paths of Glory and this young kid. I think he knew he’d probably hired him because Kirk was a big wheel in Hollywood.

When Stanley first came on board, he noticed one glaring problem: there wasn’t a battle scene originally. It was rather Shakespearean, and you know when you watch Shakespeare — It was just a way of thinking. It may have been when they first started budgeting it — I don’t know, I wasn’t there — they probably said, “Well, this is really expensive.” All these considerations come into it. And it taught Stanley a lot.

That’s why he didn’t really want to stay in Hollywood, because there are so many forces and pressures and it never stops. It’s all day and every day. And a lot of it is about time and motion studies. They actually have people on sets who say, “Well, you’re taking an hour to shoot this scene, now you’re running out of time.”

The thing about Stanley is that he moved into a situation where he didn’t have to face that on a daily basis, that he was 6000 miles away from people who would normally be injecting themselves into [everything].

Q: There are a lot of people like studio heads actually went to his estate to talk with him in person, but they can’t bring back the script.

LV: Yeah, absolutely. I remember he told me — I was actually there for some reason; doing some overdubs — and he was saying that when we were shooting Barry Lyndon in Salisbury, he had to stop shooting for a bit because Marissa [Berensen] had cut her finger. Stanley had decided the next shot was going to be a closeup of her hands on the piano, because he was shooting in sequence, no jumping about. And he said, “You’re going to see that cut, you’re going to see that plaster, you can’t hide it.”

He kept these guys waiting for I-don’t-know-how-many days in their hotel. Then they came in. One of them had a cold, so he insisted they wear breathing masks. Then he called everybody in Makeup. “Well, would you see that, was there any way you could avoid it?” “No.” So he created this wonderful scenario for why it’s impossible.

What he was doing… He was revising his script. He was using that time, and any time we could stop. In the documentary about The Shining, you see we’re in the kitchen set, and we were setting up the scene, doing the lighting and arranging everything we need, and he’s on the typewriter, still working on the script. “This scene — has it changed? The next one.” and off he goes.

It was always every opportunity he got to be able to get back to looking at the script — not as an operation, but asking “Is it changing? Is it changing?” Because he always had the courage to — he always said, he let the film, he let the story take him. Which is what a lot of good writers say, you know? “The book writes itself.” He was very much that way with his filmmaking.

Q: Why did you end up acting in Eyes Wide Shut?

LV: I was doing a lot of auditions with some very wonderful actors [at the time]. The problem was that he hadn’t really settled in his mind how originally the scene was. It was just a master of ceremonies. He wasn’t going to be masked, he was the only one who wasn’t going to be masked. It was going to be the figure of authority. Then Stanley came up with this idea that, maybe we should use that figure of authority to do that because then it’s more terrifying.

I was auditioning some 40 or 50 actors for that role, and my phone rang. I picked it up and he said, “Leon, I’ve just decided. You’re going to play that part.” And then I put the phone down. And I still had this actor auditioning for that role, and I still have to finish that audition. I have to see it out. It was such a kind of [luck] that it should happen in that moment.

You know, I played six other characters in that scene, behind a mask. That was fun.

Q: What did you think of Christopher Nolan’s yellow print on 2001: A Space Odyssey? He was probably preserving the film.

LV: I understand that the big romance with film doesn’t exist in digital. It’s just two different things, we should never try to compare them.

I did the full K print of 2001, and then I went and did the color timing on the 70mm print. They are totally different animals. You can’t think or look at them in the same way. With film, you make one color change, it’s the whole picture changes with it. Digital, you get into a little corner, you can get into a shadow area and you can keep that part the same. You can do anything. It’s a new creative tool you’ve got.

But with film, whatever you change, the whole picture changes with it. So you have to be very careful. And there has to be a lot of compromise. There really does. If you want to see deep into the shadow areas, the rest of the picture may look washed out, pale. You’ve got to figure those things out.

That’s what I love about the work. Because you’re constantly trying to figure things out and make them work in some way or another. I applaud Chris Nolan for wanting to keep celluloid film alive. He respects Stanley, and he’s a big big big big fan. Being a fan is one thing. There are millions of fans, and they all have a different idea of what something should be like, or what it should look like. But I applaud his efforts to keep it.

It reminds me of vinyl LPs coming back, maybe the same is going to happen with film, the specialized way of showing something on screen. Who knows? It becomes quite tribal in a way.

Q: After you two worked together all those years, what memory do you most love about Stanley Kubrick?

LV: The most? That nothing was impossible to approach. There was never an impossible problem. With me, the first time the laser disk came out, he had yeses and no’s about the artwork, and he was getting so frustrated with [it]. It was an album cover like an LP, a new format for a film to work in, and he was so frustrated. He said, “For God’s sake, Leon, you try something” and I said, “I’ve never done layout in my life. I don’t know how to do that.” And he said, “Sure you can. You can do it. Just try it.”

That’s actually one of the biggest influences he had on me. Because there were times when I’d think, “Ehhhh…” about anything. Then I’d think, “Well, it’s just a try.” Sometimes you do get further and further, a better understanding, and you come out again: “Well, that wasn’t so bad after all.” It keeps things optimistic, in a lovely way.

Here’s the Trailer.