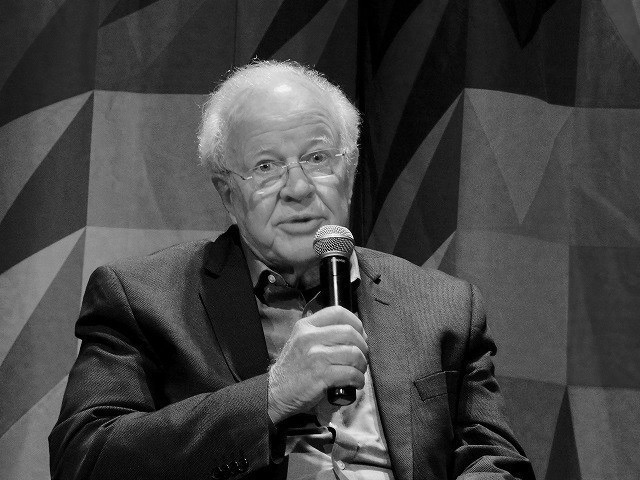

About a week ago, we’ve lost the greatest special effect pioneer, Douglas Trumbull who brought impossible cinematic experience in “2001, A Space Odyssey,” “Blade Runner,” “Star Trek: The Motion Picture” and “Close Encounters of the Third Kind.” I had a chance to see him in person for the special screening of “Brianstorm” at the MOMI(Museum of the Moving Image) in 2019. After the screening, he talked about working with Stanley Kubrick, Ridley Scott, and his directorial film, “Brainstorm”..which faced the untimely death of Natalie Wood.

Q&A with Douglas Trumbull, A Special Effect Supervisor

Q: It must be incredibly special [seeing “Brainstorm’] and having the experience you’ve had this evening seeing the film projected in 70 millimeter.

DT: I haven’t seen the 70mm print for so many years. It was quite an experience for me. So I want to thank you all for coming, a really great audience. You guys all laughed in the right spots. The movie breaks my heart

Q: Because of the story behind it?

DT: No, because of Natalie Wood and the whole thing. So it was very powerful for me to go back to that time and see that movie. It was a great job that everybody did. I’m very proud of the film. I was saying earlier that Cliff Robertson – the story that created the movie was that he was blacklisted in Hollywood because he was associated with David Begelman, and I really fought for Cliff to get this job. Then he got it, and he did a great job. Just so you know, I haven’t directed a film since this film. Something that happened, associated with this, just destroyed my career.

Q: We’re going to get to that. But I want to [talk about] Cliff Robertson in the film because it’s think that Christopher Walken won an Oscar in the years prior to this. Three of the four leads were great actors who actually were not getting work in the years preceding this film. That doesn’t seem like an accident in terms of your now wanting them. So do you recall how the casting goes?

DT: Well, I can’t take 100 percent credit for the casting. There was a lot of pushing that happened at the studio, because there were a lot of relationships in play that had to do with different people in the creative fields and people that were dealing with the agents. They started with MCA and they knew all these people for many, many years and so they had a lot of pull to get them in. I’m really happy with the way it came together. Louise Fletcher, in my heart and my mind, really stands out, an outstanding actress of any performance.

Q: That’s the given reading for a romantic part, but that’s not the thing she was getting.

DT: Yeah. No, I like to cast people against type, and I certainly did with Bruce Dern a long time ago.

Q: You must find that the actors that you meet are not like the people that they play on screen.

DT: Particularly the bad guys. It’s usually the sweetest people that you could ever meet.

Q: Another case is Christopher Walken, who was celebrated at that point and has been celebrated since. It’s much later in his career that he has been recognized as being a real physical actor. And you see him being so physical in this film and so free, and there’s a sort of bounce to him.

DT: Yeah. A lot of that is me. I try to bring that out in people. Because I don’t like movies that are really all diabolically bad and negative and everything turns down. I want everything to come out okay.

Q: And you got scientists who were allowed to have – they were not just brainiacs, all those whose offering is, remote, unrelatable.

DT: Oh, I’m a very technology-oriented filmmaker. I feel that making movies is a technological art form. I mean, if you want to be by yourself, write poetry or something. But if you want to make movies, you have to collaborate with people and it’s very technical.

One of the big backstories of “Brainstorm” is that prior to making “Brainstorm” I had developed a new motion picture technology called “Showscan”. It was 60 frame-per-second in 70 millimeter on giant screens, and it was really spectacular, it was a major breakthrough. The management at Paramount Pictures – I was working for Paramount and I said “This is the most fantastic thing. We have to make a movie.” And they said “Well, go find a movie and make it in Showscan.” And that became “Brainstorm”. It was originally “The George Dunlap Tape” written by Bruce Joel Rubin, who was also a filmmaker in his own right.

We adapted it with the idea that we would do part of the movie conventionally – you know, 35 millimeter, 24 frame-per-second film. And then when you go to the points of view, you would have 60 frame-per-second, 70 millimeter. It was a completely different animal, a tremendously different sense of immersion and realism to it.

That was the initial idea. That’s what drove the development of “Brainstorm”. And that was a crushing blow to me when I couldn’t get any studio to agree to it. They don’t like change. They didn’t want to change the frame rate or anything, because it meant changing theaters and changing screens, and everybody was scared to death of it. I couldn’t get it to happen. It was really a big setback for me personally to not make that breakthrough, which was planned.

Paramount had gotten completely distracted by “Star Trek: The Motion Picture”, which was in deep trouble. A very long story, I don’t want to waste too much time, but I got kind of skyjacked into doing the movie in exchange for getting the Showscan process back and getting “Brainstorm” back. So I rendered a year – no, seven months of diabolical work on “Star Trek” in order to get my life back. To get out of my contract with Paramount.

So I was a free man, I had this process, and I went around town looking for a way to get “Brainstorm” made, and David Begelman said yes. He had started seeking me out, and the reason he was doing that – not that he ever kited checks through Cliff Robertson – was that “Close Encounters of the Third kind” ” had made his career. Columbia Pictures — which he was the head of at the time when he kited the checks – was about to go bankrupt, and we saved him. We saved the studio from bankruptcy by making “Close Encounters”.

So he remembered that, and when he got fired from Columbia for other nefarious stuff, he settled it at MGM, took it over, and then sought me out to make in the end. So I said “Hey, you got the money, you want to make the movie, I’m ready to go.” But I couldn’t make it in Showscan. That was where the idea of changing film formats and aspect ratios came in. That was the fall-back.

Q: So you didn’t have a frame rate but you did still use 70 millimeter.

DT: Shot in 70 millimeter to show the points of view, 35 millimeter for the rest. And then changes to aspect ratios goes from monophonic sound for a small screen to stereo sound with Surround features in the point-of-view shots.

Q: It still really plays and it’s quite a different format.

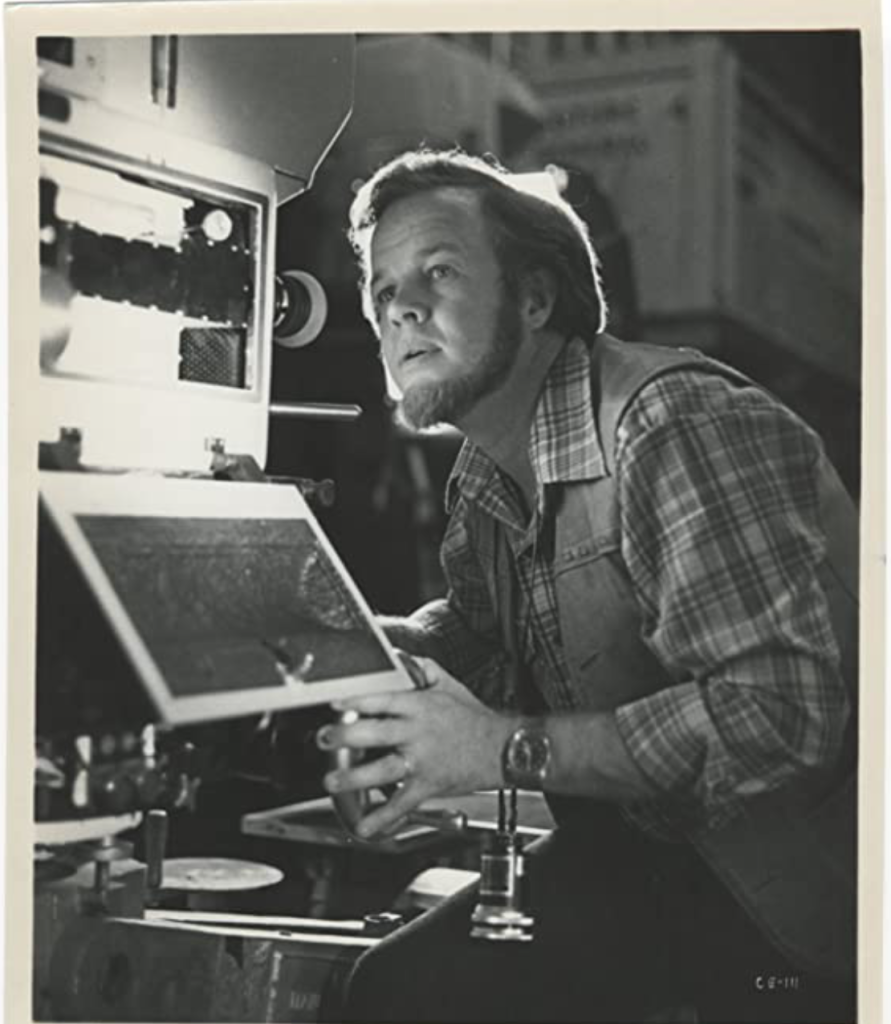

DT: I’m happy with it. I’m not complaining. But I’m telling you that right now, I’ve got a whole new animal and I’m trying to get some movies made, and I’m really having a hard time. I’ve been working in 120 frames per second, 3D 4K, and I have this new process I developed called MAGI. It’s enabled by digital projection. I was able to take a whole new look at cinema. I’m going to tell you a geeky story. I hope you guys are up for it. I was a young guy working for Stanley Kubrick on “2001”. I was a young animator, and I had never directed a film and I was working with this master film director, and I’m really lucky to be there.

Q: You were 23 or something?

DT: Yeah. So I was in charge of the stars. I painted every star in “2001”. I landed in the niche department so I shot all those stars. One day we were doing star tests. Because he would do this really funny thing that was really interesting, of taking shots of stars going right to left, top to bottom, left to right, from the top, whatever, at different speeds. And then we would double-project them with other shots to see how those star movements affected the spacecraft movement.

It was a [revealing] experience. We noticed that if the stars moved too fast, they became double stars. If they moved a little faster, they became triple stars. I said “What the . . . ? I didn’t shoot those stars, triple stars. Look at the film.” And that’s when we realized it was the double-bladed shutter in the projector. All projectors around the entire planet were making double stars.

This was the geek discovery of my early days which was, he had to slow everything down in order to avoid blurring. That’s the result of the 24 frames per second movie standard. That standard was established in 1927 on “The Jazz Singer”, the first talking movie. He had to stabilize the rate of the film when he ran it in the motors at 24 frames. So that got me on the high frame rate jag. I’ve been at this for fifty years, trying to do high frame rates. And I finally figured it out. I made this really cool discovery.

This is film. You have a digital projector up here. When you are running a digital movie, the projector is running at 144 frames a second all day, every day. Each frame is projected five or six times, and there is no shutter. Just wrap your head around that for a minute, and you realize that the potential high frame rate is built into 20, 30, 40 thousand theaters around the world already, and no one’s using it.

Oh – it shows, I figured it out. It’s cheap, it’s fast, and everybody should use it. There’s no reason to complain. So that’s what I’ve been doing. I figured out how to make an easy-to-use cinema package which goes to all the theaters. They’ll run at around 120 frames, 3D, and it looks absolutely fabulous.

I’m trying to make a movie in this because my whole mental set is how to make an immersive movie experience. And what I found in making this movie, and other projects I’ve worked on, is it started with Stanley Kubrick. When he was working in 70 millimeter, immersive Cinerama, these were 90- to 100-foot-wide screens in theaters back in those days. They’re not around anymore.

He said “You know, I can actually change the way I direct. I don’t have to do over-the-shoulder shots and stupid melodrama and the actors’ dialogue and explain everything. I can just show it and it will be immersive.” And he started extracting shots out of the movie. Because he said “I want the audience to feel like they’re in space. I don’t want to tell a story about Keir Dullea in a pod, I want to tell a story about you being in space.” That really locked in my mind way back then, when I was a kid. And I realized he was exploring the future of cinema – even then, fifty years ago.

Subsequent to that, I came back hanging out my hat, and tried to make movies. I made “Silent Running” conventionally in 35 millimeter. Which was a lot of fun for me, because I was willing to work with actors and make a movie myself at low budget.

But I also saw that the giant Cinerama theaters were gone and then “cineplex” – the big screen got chopped into a two-plex, four-plex, eight-plex or whatever. And the “palace” of the spectacle was gone. And 70 millimeter went away. Very few people tried 70 millimeter. And he wanted to bring back the good old days of 70 millimeter. As Christopher Nolan does, as well. Well I’m sorry, there aren’t any theaters that can really show it very well.

Even this theater is very long and narrow. I’m not going to complain about your theater. This is about a thirty-foot-wide screen in a seventy-foot-deep theater. Which means a lot of people back there are not seeing a wide field of view. You get a better view here.

So I’ve been trying to redesign what a movie theater is, which is like crazy to think about — trying to change the infrastructure of the planet? I built a new theater at my studio. It’s a complete new revolutionary kind of theater that’s better than 70 millimeter, better than VistaVision, better than Cinerama, better than anything. I’m really proud of it.

I’ve been experimenting with this, and one of the fun things that’s happened to me recently is that word got out to some of my friends that I was doing this. Ang Lee has been developing a prize fight movie that he’s been trying to get made. It’s a movie about the famous prize fight between Joe Frazier and Muhammad Ali, the “Rumble in the Jungle”.

Well believe me, there’s a lot of blurring and strobing. He started experimenting with higher frame rates, and he talked to Dennis Muren, who’s a friend of mine who shot the mothership in “Close Encounters”. Dennis said “Well, Doug is experimenting with higher frame rates.”

So Ang came to my studio to see what we’d been doing, and he fell in love with it. [He said] “This is the only way to make a movie. I’m totally in.” He subsequently made “Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk” shooting at 120 frames. Sadly, he hit the wall that I hit, which is that there’s no theaters to show it in if you want 120 frames, in 3D with two projectors. He can only find five theaters to do it on the entire planet.

Q: But I’m curious. I’d love to transport back to the moment of “Brainstorm” because there’s another moment where you’re trying to pull off something along these lines, with the higher frame rate. And you’re also writing a script, you’re also telling a story that way. Was the technology motivating the story, or was it both ways?

DT: It’s both. I see cinema as one big thing. If you want to make movies, you’d better understand how a camera works, you’d better understand how a projector works. Just like Van Gogh knew how a paint brush works, and how to mix oils. Or how to hang the cameras, or whatever. Artists have to learn their craft. Great sculptors have to learn how to chip marble.

So I feel it’s a job for filmmakers to really understand the medium that they’re working in. Which means lenses, cameras, film processing, etc. Then you know what your tools are, and then you know how to apply the tools to telling your story. So that’s where I’m coming at, where I’m coming from as a filmmaker.

Q: So the story is motivated by these technological elements, and so it’s amazing for me to revisit this moment in the early Eighties. The script was probably written in the Seventies, and this was shot in 1981. And to see physical action between people being motivated by what the technology could do in that moment. It’s something to think about, connecting by modem to –

DT: It really takes a movie back.

Q: It does, and yet, that’s in principle how it works. There’s obviously a different wiring system in all of it. But the idea of connecting from one place to another in that way and have computers speak to each other. And I love this moment where there’s this sense of how prescient is this? There’s a moment where he’s got to call a video from remotely. Is he predicting that you can watch video this way? And then there’s the moment where the guy walks across the room to turn on the tape player, which is amazing. It’s like a physical manifestation of what needed to happen. But the idea was there.

DT: Well, one of the things I do when I’m thinking about those kinds of questions is, I try to make it physical enough to be worth photographing. If you make a solid state movie, everything’s in your head or it’s on a solid state drive on some cloud computer someplace in Denver, it’s not very cinematic.

I just try to find ways to make things look interesting and visual. And I’m now finding out by going at a high frame rate, you can unleash all kinds of kinetic power of the movie, which makes action scenes and movement really powerful. It’s totally blurred.

I’ve been doing some film experiments lately. I took a movie like Baby Driver” – you may have seen it – [massive] car action. Take that and put in in your Blu-ray player or whatever, and just freeze it on an action scene and you’ll see that everything is blurred. Just streets and lights. Until the car comes suddenly into focus. People turn their heads while they’re driving a car in an action or chase scene or something, and their expressions are completely unrecognizable. The audience is imbuing it with what you really can’t see.

Ang Lee doesn’t like that. He wants to see every expression on Muhammad Ali’s face during the fight. This is really interesting. The movie he is doing right now is called “Gemini Man” and he finally figured it out and he got it right. I helped him, and I’m really proud of that.

I think it’s going to look pretty great. It combines content and high dynamic range. I don’t know how in theaters they’re going to have the setup showing it. But I’ve seen big pieces of the film so far, and it’s absolutely mind-bogglingly stunning. Because it’s filled with action scenes, a motorcycle crash. And it’s got Will Smith as himself as a younger clone. Well, he plays against himself – he plays against a clone of himself who’s 25 years younger.

The reason Ang picked that piece of material was that he wanted to see the expressions on both characters’ faces when they’re facing off against each other and try to outsmart each other. The old one knows that the young one has got fantastic eye/hand coordination but doesn’t know as much as he knows. You know, those kinds of things: the old versus the new, younger versus older. I think it’s going to be a really interesting film.

And they use a lot of de-ageing. This is the big talk around what Ang calls “Junior”, which is the 25year-younger character of himself. It’s performed by Will Smith, but the Will Smith is the Will Smith of 25 years ago, with computer graphics. It’s going to be a really interesting piece of film.

To me, I really support Ang because it may represent a kind of turning point for cinema. Because it’s the one thing that can differentiate movies in theaters from movies on television. This ain’t gonna happen on your television. Or your smartphone, or your tablet. It’s only going to happen in a theater. If it gets traction and it starts making money, then Tinseltown will then pay attention. But if it doesn’t, they won’t.

Q: I’m going to [take questions from] the audience.

Q: What happened about Natalie Wood?

DT: We had finished most of principal photography. We had wrapped everything [in North Carolina], we had our sets built and on the stages at MGM, where we had done a lot of shooting, and still had more shooting to do. The thing that happened that was so stunning to me was that, shockingly, I found out – I went off.

It was the Thanksgiving weekend – it was the long four-day weekend holiday. And I’d gone off to my home in Maine to take a break from burnout. Natalie Wood and Christopher Walken and RJ Wagner went on their boat to Catalina [Island]. It’s still a mystery to me why Christopher Walken got invited on the boat at all, because RJ Wagner was really pissed off at him, in his suspicious mind.

But the minute Natalie would die, the studio declared force majeure and shut the movie down, and fired me and everybody else. What the studio was supposed to do when something goes wrong on a production – the set burns down, or something goes wrong — you ask the director “Well, do we have a problem here? What do we have to fix? Do we need a double? What are we going to do?”

Well, [studio] wouldn’t even look at the film. They wouldn’t even talk to me. This was the telling key to the fact that I think there was foul play. Because they just terminated everybody, they didn’t want to know. And I said “No, we can easily fix this movie. There’s three little shots that Natalie Wood was supposed to be in.”

A good example is there’s a scene where, in the script, Gordy, the son is in the basement of his house playing the sax flute, and they drive up outside. That was shot in North Carolina, and Natalie Wood and Christopher Walken drive up, crash into the curb, get out of the car and run into the house. Natalie and Christopher were supposed to go to the basement together. I said “Well, if Natalie’s not there when he goes to the basement, I think we can make this scene work.”

That was a good example of the kind of scene to do. Because I didn’t want to use anything that would be a body double or a hand double or a voice or a replacement or anything. I mean that house was about Natalie Wood. Being honest that what we could finish with the movie did not need any of her; that was not called for.

So I tried to tell the studio that there was no problem; they didn’t want to know. I got locked out of the cutting room. So then I knew that there was something nefarious going on.

Q: It’s crazy how that’s mirrored in the film itself.

DT: Yeah. It was completely inadvertent, though.

Q: What’s your take on VR in film?

DT: Well, my answer about that is, I have had some really stunning virtual reality, immersive dramatic experiences that I think are amazing. The problem is that you can only do it with one or two or three or four people at a time in the best situations that I have seen. It’s very hard with VR to entertain a whole crowd like this, or VR with four hundred people. So I don’t see a viable business model for how to create dramatic entertainment.

One of the other problems I see is that young people who are really becoming fascinated with virtual reality think that having an immersive experience is all you need. They don’t think you need an actor or a script or a story or a plot or structure — or a director. And I would say I just think you’re dead wrong. Because you need all those things.

The MAGI process is a fully theatrical process that you can show to as many people as you want in a theater. And I just want to change the theater to be better. So there is no limitation to it. But it’s stupidly easy to do and I hope it takes off.

I’m not absolutely certain that the footage that doesn’t exist actually doesn’t exist. I’ve been told that. And here’s one of the problems in that sense, an interesting little geek story, too.

MGM basically folded and went out of business, and the entire MGM library – including “Brainstorm” – was purchased by Warner Brothers. Everything got transferred to Warner Brothers. I had been told during those grim times we were trying to get “Brainstorm” done that all of the water-related material we shot was destroyed. I was told by management that had happened. If it didn’t happen, we just didn’t know otherwise.

Well, what I found out subsequently in working with Warner Brothers, I was trying to make a really good documentary film about the making of “2001” that I was developing with Warner Brothers. They owned the stuff. I found out that all their outtakes, B rolls and negatives were in some salt mine in Kansas. I thought whoa, that’s really interesting.

So we started probing into the salt mine and getting the inventory list of what’s in the salt mine. We found stuff that people thought didn’t exist, including outtakes from “2001”, the missing prologue that we shot for “2001”, the seventeen minutes of material that was cut out of the movie after the first opening. All that existed in the salt mine.

So one would question: maybe we’ve got some “Brainstorm” stuff in the salt mine. It doesn’t really matter to me, because I’m not going to go back and do that again. I don’t want to revisit this movie again. And I don’t want to make a point about it or anything.

Q: “The Hobbit”: Why do you think it didn’t it work?

DT: A lot of people reviewed the movie, looked at the movie, and said well, the high frame rate looked like a soap opera. Which meant it looked too much like television. And I’ll tell you another geeky story, which is part of what I’ve been discovering recently when probing into this territory.

He shot in 48 frames instead of 24 so he doubled the frame rate of 24. He also nearly doubled the shutter aperture on the camera as a safety play so that if he had to release the movie in 24, he could take every other frame to leave the frames in between and still have a reasonable shutter opening so there would be enough blur. And that worked. That’s how the movie came out.

But the higher frame rate version was 48, and because the projectors were digital and because the nature of the PCP package was made for theaters, he didn’t realize – I don’t think anybody, today even, realizes it – each frame still gets shown twice. Not just once. You don’t solve the problem of motion and motion continuity unless you show each frame only once. And the sequence of frames has to be projected exactly as he photographed it.

He was projecting 48 frames at 96, and then the projectors alternating left-right, left-right left-right because there’s a spinning polarizer or electronic circular polarizer on the projector to make it 3D. And there’s no shutter at all. The fact that there’s no shutter makes it look like they – this video has no shutter. So you just get a natural inclination to keep it the same.

It looks like television to me. People don’t know that there’s a shutter or not a shutter. I said tonight there’s definitely a shutter in the projector. I can see the flicker. I’m too sensitive to flicker, probably. Maybe you’re not. But I’ve been in this territory for a long, long time and I’m very sensitive to it.

And it’s one of the things that’s just not understood. If you ask any major director – go to Steven Spielberg or George Lucas or anybody – and ask them how the digital projectors work, they don’t know. So they don’t know how their movies are being shown.

Q: What are your insights now about the “evil” military co-opting the new technology to use for torture?

DT: It disappointed me, too. I’m not going to argue with what I did. I think it’s one of the biggest mistakes I’ve made and the trap I fell into, a typical normal, melodramatic trap of trying to make some evil force work in the movie. And I regret it. I think I should have found another way. That’s the best I can say.

The other stuff – if anybody here knows about Esalen — it was a drug-free, nontoxic healing technique for holotropic breath work, which was a way of evoking, in any human being who does this technique, a kind of a rite of passage, rebirth kind of process which can clear up all kinds of negative baggage that you’re carrying in your psyche and in your mind and your heart.

Stanley and Christina [Grof] felt that it was an extremely powerful and important thing to do, and I agreed with them. I wanted to use it because of this movie and this whole process that Stan talked about, which was kind of a rite of passage.

He said “The movies are about the same thing all the time. You set up a situation and then you make it worse. And then you make it even worse. And then you have a resolution at the end.” A three-act play structure. He said it pervades all literature, all art, all music, and that’s the way the world works. And we’re all built that way because we were all born and we all went through the birth process which was very traumatic.

If you want me to go on, I can tell you about how it’s built into this movie. There [are] four important stages of it: prebirth, the beginning of a crisis, the crisis gets extreme and life-threatening, and then the result, which is birth which is hopefully a happy emergence back into a positive state. He found that people who get through the whole thing would come away feeling much better, just generally euphoric or whatever.

The idea behind this movie was to hopefully leave the audience feeling that way. I just don’t think I was ever able to achieve that, a hundred percent of that goal, because of all the stuff we were going through and that I had to go through with this movie.

And then the interesting conclusion of that whole story is that I used it myself to survive and recover from making this movie. I had Hollywood PTSD. I sold my house, I sold my car, I moved out of L.A. and I moved to the Berkshires to try to recover myself. I said “I’m not even going to make movies anymore. This is what they do: they kill people in Hollywood. Count me out.” That’s the way I felt.

So I just came back to try to have some weather and some nature and some solitude. I found some really good therapists to work with me and help me do holotropic breath work which I did, a lot. Until I was screaming and crying and furious and went through a very cathartic releases of all kinds of things and energy that was carrying me because of this movie and the way I was treated by the studio, and by the lawyers and by everybody else. I personally recovered from it, finally. It took me a couple of years to recover from this movie. And it was thanks to Stan and Cristina.

Q: Because there’s something beyond it. And then there’s some things like an electric chair type of shot when he first puts it on, which is so loud and so terrifying and so brief. There is something so perfectly calibrated about it. But the end of it is a sonic attack. And also, you have this sense of – I don’t know if you felt this way, it goes like “I can’t take this another second” and then it stops. Just that amount of time.

DT: Well, that scene was a replacement scene. The script called for a drowning scene. The whole story was built around a boy and his problems, or relationship with his parents who were breaking up were the trauma that he was going through.

And in the traumatic episode scene, he sees them drown him. They force him into the pool and drown him. He’s attacked by eels and monsters and giant propellers, and it was a really dismal drowning scene. That we hadn’t shot yet. That was part of the post-production we lacked.

So the studio said “No way are you shooting that scene. We’re not going to go anywhere with drowning or anything. That would be really bad.” So I reluctantly agreed to rewrite that scene and restructure it as this kind of Frankenstein laboratory thing. Which worked fine. I’m glad you liked it.

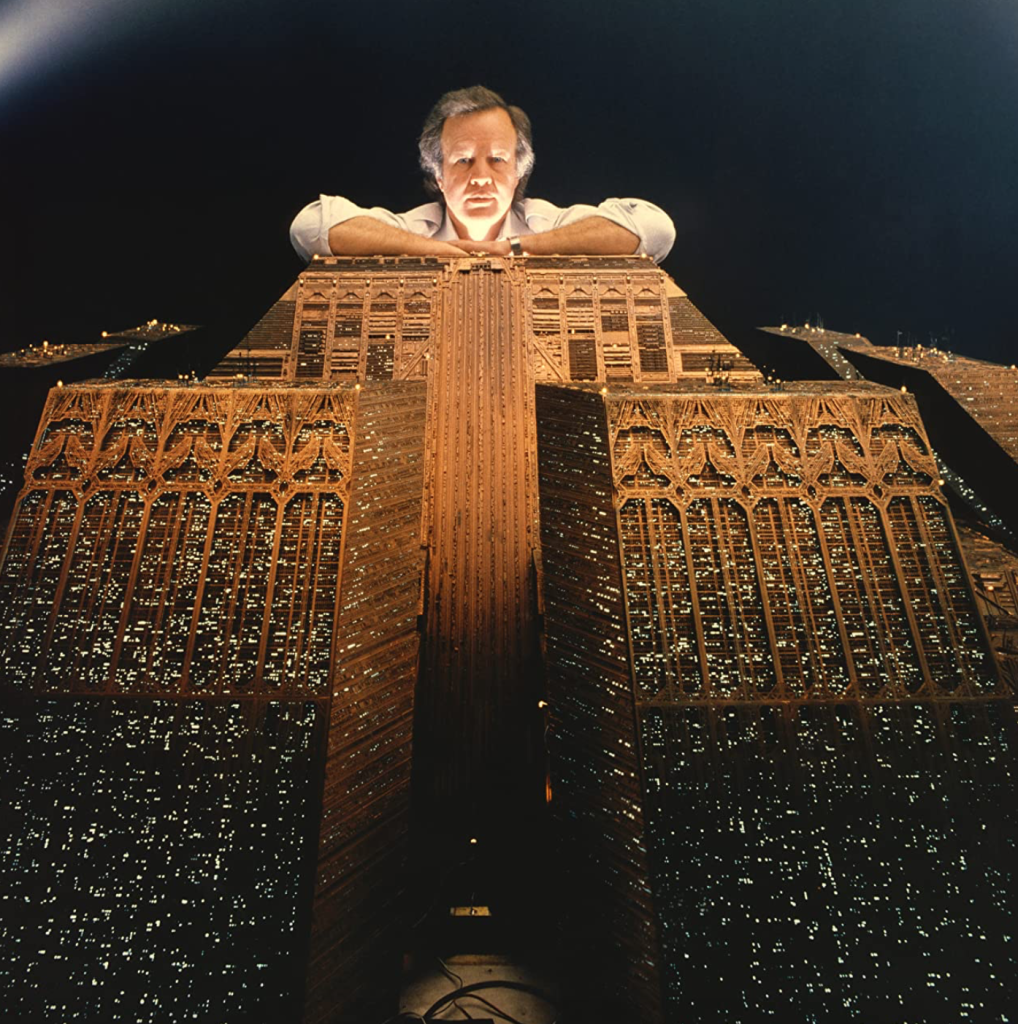

Q: Have you seen the Mark Stetson model upstairs in the collection from the Tyrell Corporation? [Blade Runner]

DT: Yeah. Yes I have.

Q: Can you talk a little bit about your experience working on that, and also how that impacted the movie we just saw?

DT: Very little. I think in terms of photographic technique and things we learned to do, there’s very little of “Blade Runner” in this movie.

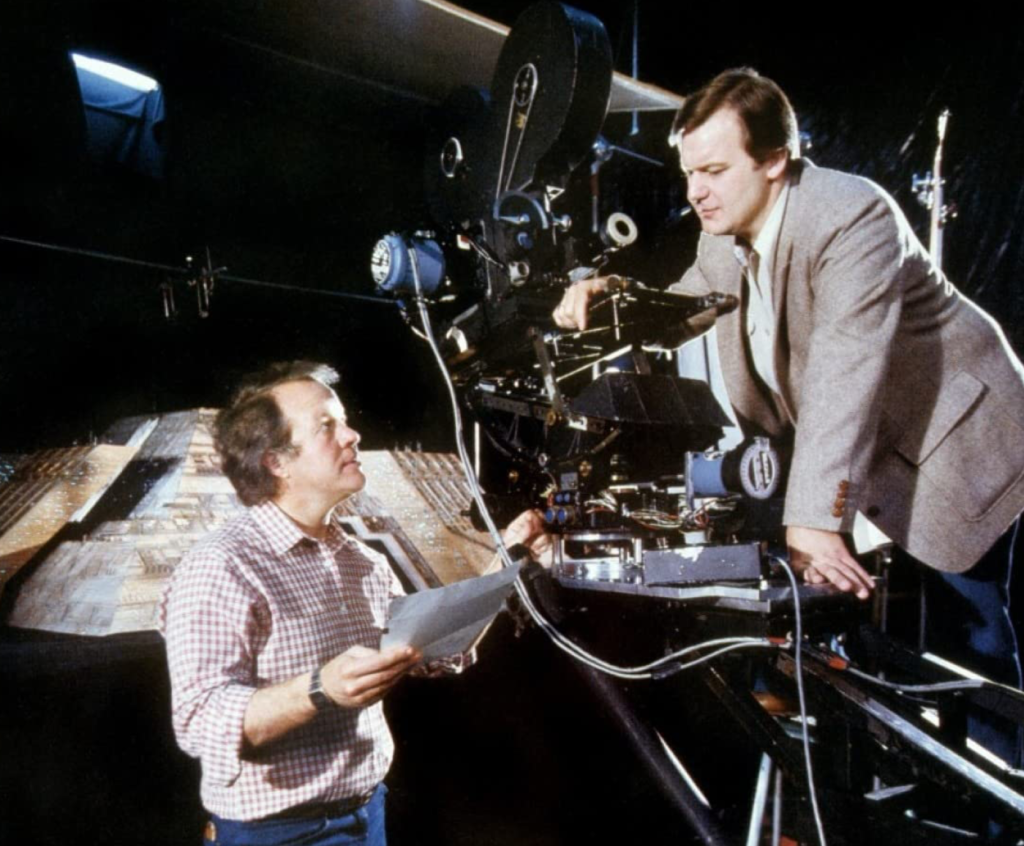

Q: You were working on it at the same time, is that right?

DT: Yeah, they were overlapping each other. It was a deal that we had to make with the studio and Ridley Scott. We had to tell them we knew that there was a conflict in the schedule, that I was going to direct “Brainstorm” and Richard Yuricich, my partner at my company, was going to be the director of photography on “Brainstorm”.

So we had to find another guy to step in for us, and so we brought in a really wonderful guy, David Dryer. He kind of Segwayed out of it, and he Segwayed into it and took over for us. It was actually a good thing for “Blade Runner” because we were our backup and he was fresh horses.

So Dave Dryer came at it with new energy and added stuff that we probably would have been too fatigued to even try. We added a really nice level of tinge to “Blade Runner” in those shots.

Q: What do you think of all the possibilities of all the streaming media now and big demand for content?

DT: I can answer that question in two ways. One is, what do I think of streaming: I think it’s really interesting that there is so much opportunity for filmmakers to make tons of movies. So this almost unlimited amounts of money being spent to create enough glut of movies, of episodic stories. I have nothing against that. There are some really good ones.

Here’s the second part of what I think: It commoditizes the filmmaking process. I don’t know if you’re aware of the business mechanisms going on. If you’re Ridley Scott – who is a really fine, mature, serious filmmaker – if he makes a television series for Netflix or somebody, he gets no profit. He gets bought out. There’s no back end. Nobody gets a back end in streaming.

That’s the diabolically bad part of the business side of dissonant franchising the creative talents. Who don’t passionately go the extra mile to make their passionate movie. They’re not going to do it. What’s the difference? It satisfies the network or the people who are in charge, and they just crank it out. So it becomes what I call commoditized, which is a negative term in my vocabulary, because of the differentiation of the passion that I’ve seen from many filmmakers that I’ve worked with.

I’ve been really lucky to have worked with Ridley and Steven Spielberg and a lot of people who were passionate about making movies. And they are also passionate about succeeding, so they care about it passionately. Because they know there may or may not be profits. If they screw up, there’s no profits. If they do a good job and please their audience, there will be profits and they will get some. They will become rich. Not in streaming.

Q: Would you ever take “Brainstorm” into an update, maybe in a series?

DT: Yes, I’ve been thinking about doing something on “Brainstorm”. It’s really tricky right now because it’s been so many years since this movie was made. This is very dated. But in the context of virtual reality, right now, and in the context of streaming right now, there may be a way to rebirth this as a new kind of high tech medium that takes advantage of things like MAGI or virtual reality and actually makes that part of the story.

If you have 3D, for instance, it had better be an integral part of what story you’re trying to tell. Don’t just paste 3D onto a love story because you think 3D is going to make more box office. You have to have an integral and legitimate reason to do a technology in a movie.

So if I could do a “Brainstorm” remake or a sequel or a reboot, or whatever you might call it, I’m not so much interested in an episodic version of it. Although I think we could do it. I’m more interested as a filmmaker in making a totally immersive experience like I intended to with this, because I have the process now. I know what works. I’ve got the cameras now, I know how they work. I can remake something like this that would be mind-bogglingly immersive. It would take it to another dimension. And we could even use the trick of cutting back and forth between two mediums in the one movie.

Because I can dynamically change the frame rate and the color on any frame or any object. You can have a movie now that has – it could be a 24-frame-per-second movie with a 120-frame-per-second 3D monster in it. You can do anything you want now. It’s so expanded that we can do anything. So I’d like to explore that.

I’ve got a movie that I’m really, really passionate about making which is called “Light Show”, which is kindof beyond “2001”. Because I love “2001”. I think “2001” is one of my favorite movies, Kubrick one of my most favorite filmmakers, it’s one of the most intelligent movies ever made. And I really admire that. So I’ve been working on an idea for a similar kind of a space adventure and going to another star.

I went to a thing that NASA held down in Florida called 100 Year Starship Symposium. A lot of really serious people – like Arthur Clarke-type people – speculated on how could we get to another star. If we had to abandon Earth and get someplace else, and colonize, how would be do it and how long would it take and how would we go about it?

So I’ve been writing a story about that. It’s really a quite beautiful epic thing. And it does involve contact with aliens, more like there was in 2001. I don’t think I want to see green reptilian monsters, that’s not my cup of tea. But talking about super-intelligence gets so over we can fathom what it is, is good.

And stuff like what was in “Forbidden Planet” a long time ago. It was a seminal movie for me. We never see the aliens, but just implying their existence and their abilities, I thought was good in itself.

I’d like to make a movie like that and use my process because my objective would be to make you, the audience, feel like you are on that ship and you are personally on that adventure yourself. That’s what Kubrick was trying to do with “2001.” It would make you feel part of the movie. And not connect with it through empathy. You empathize with the character, so you worry that he’s going to die because you think you are going to die. I want to you to actually feel like you’re going to die. Whether you’re in love or anything else.

Because I think it’s possible. The medium is now about to change enough to where the relationship between the audience and the movie is going to be profoundly deeper. That requires a new kind of story and a new kind of directing style, and a kind of slight shift in cinematic language to do it.

Q: Thank you all for staying.